by Ken Gargett

Back in 1984, the highly respected English wine magazine Decanter announced its first “Man of the Year.” The winner was Serge Hochar from Chateau Musar in Lebanon.

The decision, at first sight, was a touch controversial, and some wondered if the magazine was more interested in making a splash than honoring an appropriate recipient. That was nonsense, of course, but at the time a lot of wine lovers had never heard of the winner, Serge Hochar, or his winery, Chateau Musar. Many had no idea that anyone was even making wine in Lebanon.

Even if they knew, surely it was more a curiosity than a competitor for estates like Château Latour, Château Lafite Rothschild, Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, and many others (representatives from these and many more would follow over the coming years as recipients of that same Man of the Year award). But then, no one at those estates had ever had to make wine in a war zone (well, at least since the 1940s).

Chateau Musar wines

Anyone who has enjoyed a bottle of Chateau Musar will know full well that this can be a wine of exceptional quality.

The wines had only first been shown in the UK a few years before, at an exhibition in Bristol in 1979, but the winery was in operation for many years before that.

Serge Hochar sadly passed away at the very end of 2014, dying in a swimming accident while on holiday in Mexico. He was 75. Hochar was a leader, not just for his own wines but for the Lebanese wine industry. He was hugely respected and admired by all who met him. At the time, it seemed every second wine critic on the planet had a personal story about Hochar, giving an idea of his enormous impact and influence. Mine is a bit of the proverbial damp squib.

Ken almost meets Serge Hochar of Chateau Musar

Around a decade ago, I ducked into one of Brisbane’s best wine stores to catch up with a couple of mates who ran it. Imagine my shock when I saw that the man carefully studying the many bottles on the shelves was the legendary Serge Hochar. I headed down the back and asked my friends why he was here – normally, I would hear about any planned tastings or dinners when a winemaker comes to town (usually, they have red carpets strewn before them with endless events). But this time, complete silence.

My friends were stunned to learn who they had in their shop, so I suggested we go and welcome him to Brisbane. Too late. When we turned around, he’d already disappeared. I checked with his importers at the time as to what was happening. All they could tell me was that they knew he was in Australia for a holiday but had no idea where and no wine events were planned. In retrospect, I am a bit glad we did not disturb his holiday.

Wine in Lebanon and Chateau Musar

Lebanon has an extensive history with vines being cultivated there for some 6,000 years. Vines were brought to the region by the Phoenicians, who then took the wines around the Mediterranean.

Musar is located at Ghazir, 24 kilometers north of Beirut, with vineyards situated in the nearby Bekaa Valley, which sits at an altitude of 1,000 meters. The operation was established by Serge’s father, Gaston Hochar, in 1930. Serge took over in 1959, after convincing his father to step aside, with brother Ronald running marketing and finance from 1962.

Serge’s sons, Gaston and Marc, now run the winemaking and commercial aspects respectively, while nephew Ralph was in Australia recently to promote the wines. It seems Marc has some of the family’s famous sense of humor, having been quoted as saying that, “My brother looks after the liquid, I look after the liquidity.”

In 1930, and for some time after that, Lebanon was ruled by France, with Musar suppling wine to the local French troops. This all came about, if one may be forgiven for summing up a nation’s history in a paragraph, as the League of Nations, in dealing with the partition of the Ottoman Empire, decreed that France would administer Lebanon, which later became part of the French Colonial Empire. Naturally, the French influence promoted a culture of wine drinking.

Charles de Gaulle was posted to Beirut for two years in the early ’30s. A Major Ronald Barton was also assigned to the region – the Ronald Barton from Château Langoa-Barton and Château Leoville-Barton, two highly respected estates in Bordeaux. By a rather nice coincidence, Ronald’s nephew, Anthony Barton, who succeeded Ronald at the two estates, was named Decanter Man of the Year in 2007. Ronald and Serge became great friends with Barton assisting Musar in the early days, so much so that Gaston’s second son, Ronald, was named after him. This is partly why it is considered that there has always been such a strong link between Musar and Bordeaux.

Serge was born in 1939 to a family that had originally come from France at the time of the Crusades. He took over in 1959, at the same time completing his course at the University of Oenology in Bordeaux (he had previously studied civil engineering, but the wine bug bit), working with the legendary Emile Peynaud (although some years later, Serge apparently told Peynaud that he made wine in exactly the opposite way Peynaud had taught him).

Sales were largely local until the start of the Civil War in Lebanon in 1975, which ran until 1990. At that time, they looked further afield. The international exposure began at the Bristol Wine Fair of 1979 when several locals chose the 1967 Musar as the wine of the fair. Musar soon became a favorite wine of author Auberon Waugh.

Serge never stopped traveling the world and promoting his wines and those from his country. He even once went to Antarctica as someone took a bottle of Musar there. He was a great advocate for the terroir of the Bekaa Valley.

Chateau Musar’s wine cellar

Despite the war raging about them, Chateau Musar has been made every year with the exception of 1976 when there was no electricity at the time and the roads were impassable. The 1984 was made but never released – it had to be taken a very long way around to get to the winery, including a section by boat, and it had started a premature fermentation while at sea – while the 1992 was considered not to standards and declassified.

As a driving force in the Lebanese wine industry, Serge’s contribution can be seen in that at the end of the war in 1990, there were only five operating wineries in the country. Twenty-five years later, there were ten times that number.

Chateau Musar and the civil war in Lebanon

No one should underestimate what the family and the winery (and, of course, the country) went through in those days. They had to deal with shells landing in their vineyards and even flying overhead during harvest. The wine cellar was turned into a makeshift bomb shelter.

On one occasion, Israeli tanks arrived at the winery. Normally, it was a quick trip from the vineyards to deliver grapes to the winery, but in 1990 the front line of the war shifted between winery and vineyard and they needed to detour for some five hours to get the grapes to the winery. Some years that took ten days.

In 1982, Chateau Musar’s vineyards became the frontline for Israeli and Syrian tanks. Harvesting of the grapes was only able to occur during the occasional lull in the fighting, at which time the loyal Bedouin grape pickers would bolt into the vineyards and grab what they could. That wine is now one of Musar’s most admired and has been described as “typically Musar in its enigmatic simplicity/complexity.”

Serge has spoken about one evening when bombs were falling in nearby Beirut. He refused to abandon his winery and instead opened a good bottle of wine, sitting by himself and enjoying it. “I poured a whole bottle into a big glass. Every time a bomb hit, I would take a sip.”

Despite all this, Serge was once quoted as saying that, “Wine is above politics, wine is tolerance.” He also described wine as, “An answer to the mystery of existence.”

Chateau Musar

Musar has around 220 hectares of vineyards, which were certified organic in 2006. Key to the family philosophy is working both the vineyards and the wines with “minimal human intervention.” As mentioned, the valley sits around 1,000 meters above sea level. It is flanked by snowcapped mountain ranges. The valley averages around 300 sunny days a year with an annual average temperature of 25°C.

Chateau Musar 1961 vintage

Musar is most famous for its eponymous wine, Chateau Musar, but it also makes other wines, including a red for earlier drinking called Hochar, a single-vineyard wine, and a white.

The white comes from Obaideh, which is related to Chardonnay, and Merwah, related to Semillon. It is a richly flavored style that also needs many years. The reds are varying blends of Cabernet Sauvignon, Cinsault, Carignan, Grenache and Mourvèdre. So expect a form of Bordeaux and Rhône blend, but it is distinctly Musar. Chateau Musar is, if nothing else, a wine designed to age very much for the long haul. The winery also makes an arrack called L’Arack de Musar.

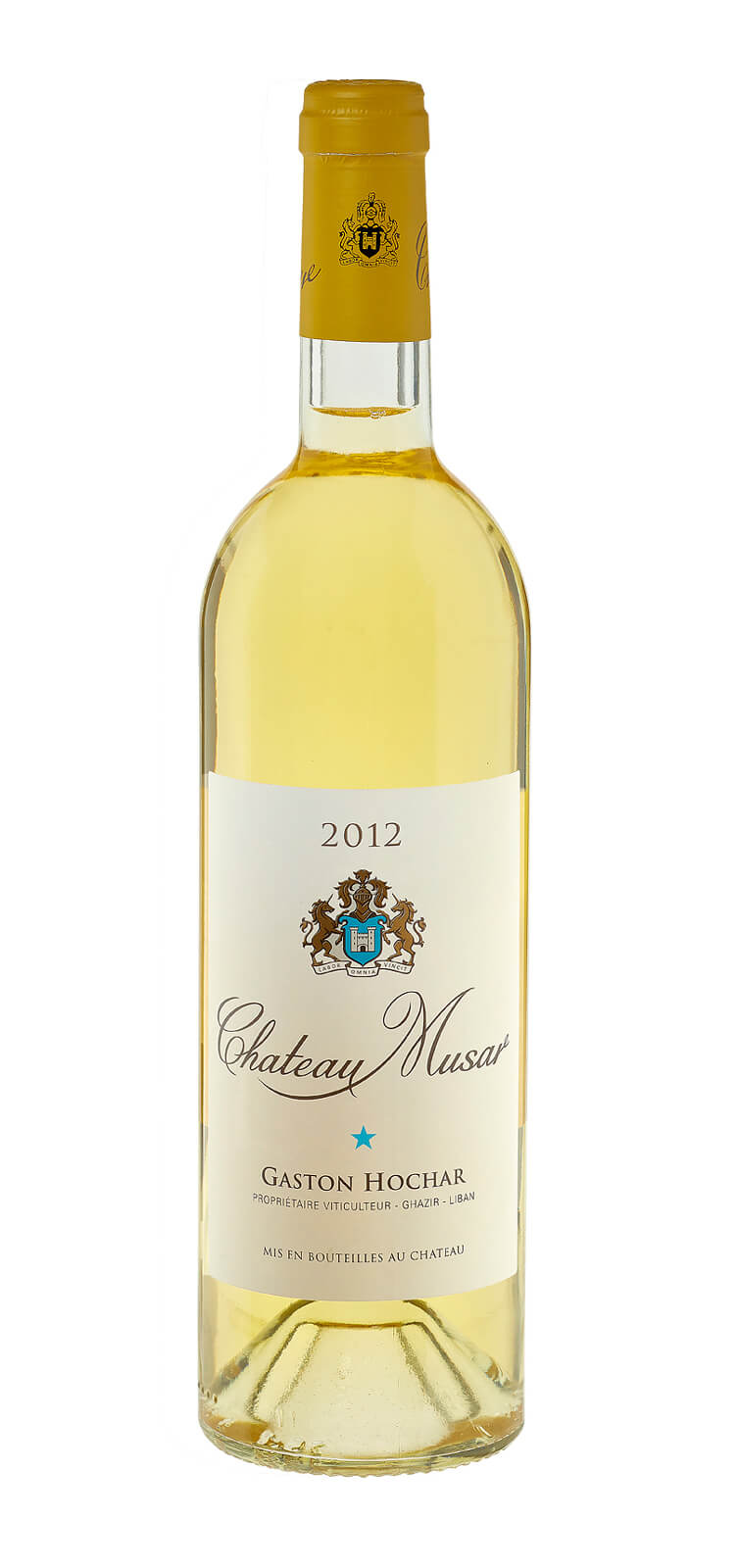

Chateau Musar 2012 white wine

Chateau Musar: the wines

The flagship Musar is a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Carignan, and Cinsault, usually in reasonably similar percentages. The vineyards in the Bekaa Valley are gravelly soils over limestone, having been planted from 1930 onwards. The average age of the bush vines is 40 years. The components undergo a lengthy fermentation in closed-top, unlined cement vats at temperatures below 30°C. Fermentation is by natural yeasts.

Chateau Musar’s oak wine barrels

After six months, the wine is transferred into French barrels (Nevers oak) for 12 months. Eventually, the discrete components are blended and returned to the cement tanks for a further year before bottling without fining or filtration. The wine then spends a further four years maturing in bottle in Chateau Musar’s cellars. It means that the wine is not released until it is seven years of age, though it has many years ahead of it; 2015 is the current vintage.

Serge was always keen on the wines showing the inconsistencies of vintages. He did not want the wine to taste the same year after year. As he once said, “I don’t make wine for consistency. I make wine for inconsistency.”

Chateau Musar 1995 rosé

The wines have always been controversial. Some love them, others do not. Indeed, I would suggest that very few elite wines divide opinions as forcefully as do the wines of Chateau Musar. They are especially popular with today’s generation of natural winemakers. The funky characters are adored by some but often described as flaws by others. The wines also have a tendency to edge to brownish notes relatively early, but this should not be seen as a sign of early ageing. One man’s poison . . .

A major issue is the character of VA – volatile acidity – which is very much part of the style. Many technical winemakers insist that this is a fault and should be eradicated. Others find it a natural part of winemaking. It is worth noting that many of the earlier vintages of Penfolds Grange exhibited noticeable traces of VA and it certainly did no harm. I guess the lesson is that if you prefer pristine wines (and absolutely nothing wrong with that), then Musar may not be your cup of tea.

Oxidation can be an issue for some, and the use of sulfur, or lack thereof (minimal amounts are used), can be questionable.

As mentioned, 2015 is the latest vintage. The estate describes it as, “One of the most challenging vintages in a generation.” It started well with plenty of rain and snow before temperatures rose, but in mid-April the temperatures at night fell to between -8°C and -12°C, destroying buds.

It left vineyards full of “blackened vines.” The team described it as “catastrophic,” but, gradually, green shoots emerged from the stems of the vines. Nature was not finished and threw a heatwave at the vineyards in September. Losses were between 50 and 70 percent, resulting in a tiny vintage, but the reports were that, despite the challenges, a wonderful wine had been made. Naturally, I was keen to try it (as an aside, it is worth noting that the 2018 Hochar was a delight with fresh cherry notes).

Unfortunately, I managed to embarrass myself before we even got to the wine. Serge had been well known for believing that one only needed “the tiniest amount to taste” and clearly that philosophy still operates within the team. When Ralph kindly poured me a tiny amount during his recent visit, I assumed that this must be to rinse the glass from previous wines. So I poured it into the nearby spit bucket. Ralph, politeness personified, was kind enough not to say anything but the look of surprise, and the re-pour of an equal amount, gave it away.

It could be worse. Visiting a winery some years ago, I looked around for the spit bucket (a mouthful of wine prevented me from asking). Spotting it at the end of the bench, I did what one does with a spit bucket, only to discover from the horrified winemaker that it was his one and only trophy, his pride and joy. It was a short visit.

Anyway . . .

Chateau Musar 2015

The vines that provided the grapes they were able to harvest were between 50 and 70 years of age. Ruby/garnet in color, the nose is dominated by red fruits with spicy notes, leather, bay leaves, warm earth and tobacco box hints. Attractive cherry notes on the palate. Serious concentration, balance, and intensity that travels the full length of the wine.

Good complexity is already evident, and it finishes with plenty of grip. Unquestionably, a good future. Sure, perhaps a little more rustic than those who like the squeaky clean may prefer, but this is a wine full of interest. The longer you can give it in your cellar, the better. 94 for me, though this should improve with time.

‘Chateau Musar – The Story of a Wine Icon’

Finally, those interested in learning more on Chateau Musar should seek a copy of a new publication called Chateau Musar – The Story of a Wine Icon.

Surely there can be no question now over that initial Man of the Year award, nor the incredible contribution to the world of wine made by Serge Hochar and his family.

For more information, please visit chateaumusar.com.

You may also enjoy:

Yamazaki 12-Year-Old Japanese Whisky: Why Pricing Has Gone Through The Roof

The World’s Best Wine? No Contest: Romanée-Conti By Domaine De La Romanée-Conti

Penfolds 2016 Grange And G4: Superlative Wines, Well Deserving Of 100 Points. Each!

Penfolds Special Bottlings: Spirited Wines, Distilled Single Batch Brandy, And A Fortified

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!