In Praise of Anglage: Exceptional Hand-Finished Anglage is Difficult, Slow, and Expensive so the Big Brands have Given Up and Few Seem to Have Noticed (or Seem to Care): Thank God for the Indies!

by Ian Skellern

Modern high-precision machinery has revolutionized the manufacture of mechanical watches as it has nearly everything else.

In an earlier life, I was once driving a truck in India and literally had a fender bender. The panel around the front right wheel was basically destroyed and I had to remove it to be able to turn the wheels. I took it to a backstreet panel beater in Delhi, who took one look (well, two: one at the work to be done and another at the fact that I was a relatively rich westerner) and said it would take a couple of hours and around $50 to fix.

I thought that he must know where he could find an old replacement, but he pulled out a large, flat piece of sheet metal and started hammering (beating) it. And within a couple of hours, he had transformed the flat metal into a perfect mirror image of the opposite fender. He gave it a couple of coats of paint and my truck looked brand new.

He had taken a piece of raw metal and skillfully transformed it into the exact part required.

That’s what traditional watchmakers used to do. Because components could not be made to high precision in quantity, which would mean that they were interchangeable, each component had to be individually made to fit the components that it was interacting with. If something needed replacing it had to be made to fit rather than replaced by an identical part off the shelf.

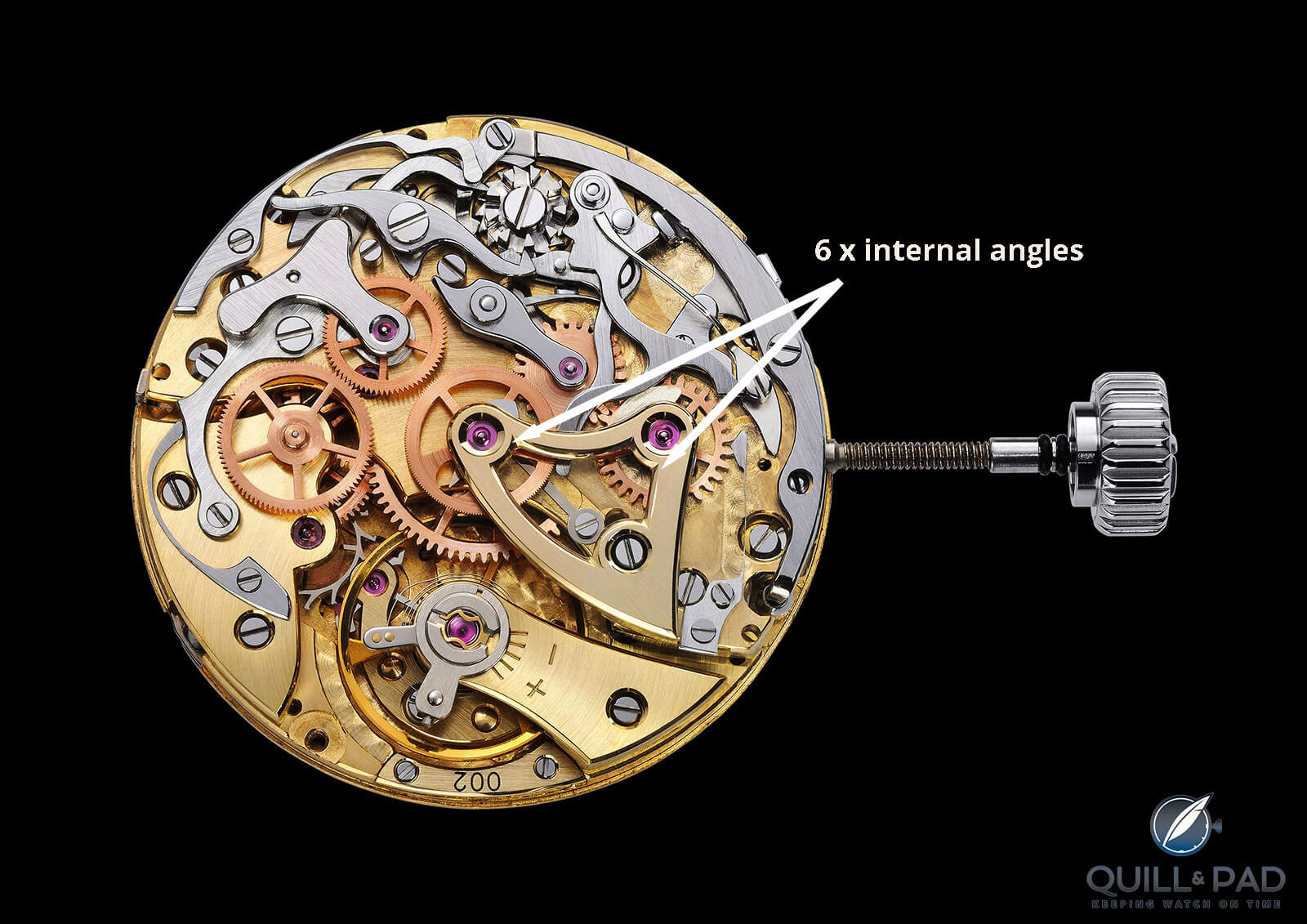

Hand anglage with 6 internal angles on one component in the Oileán H-B1 Triple Calendar Chronograph by John McGonigle

High-precision manufacturing today means that modern mechanical watches are cheaper to produce, cheaper and easier to repair, more reliable, and more precise. That’s win, win, win, win! What’s not to like?

Well, one problem is that the quartz watch is even more reliable, more precise, and so cheap to produce that you don’t even bother repairing it. You just throw it away and buy another.

And that’s what caused the quartz crisis in the 1970s to early 1980s, which decimated the (largely Swiss) mechanical watch industry.

The mechanical watch primarily as a timekeeper is dead. Long live the mechanical watch as exclusive luxury!

However, a few pioneering visionaries, including Jean-Claude Biver (Blancpain), Gerd-Rüdiger Lang (Chronoswiss), and Svend Andersen and Vincent Calabrese (A.H.C.I co-founders), thought that mechanical watches still had an economically viable place in the world, and by the late 1980s mechanical watches were transformed from being primarily timekeepers to being primarily luxury jewelry that men could (and would) wear.

And over the following decades more dormant brands were revived, and moribund brands crippled by the quartz crisis thrived.

The big haute horlogerie watch brands were no longer in the business of selling timekeepers but selling exclusive luxury. And the beauty of selling exclusive luxury is that it has fat profit margins.

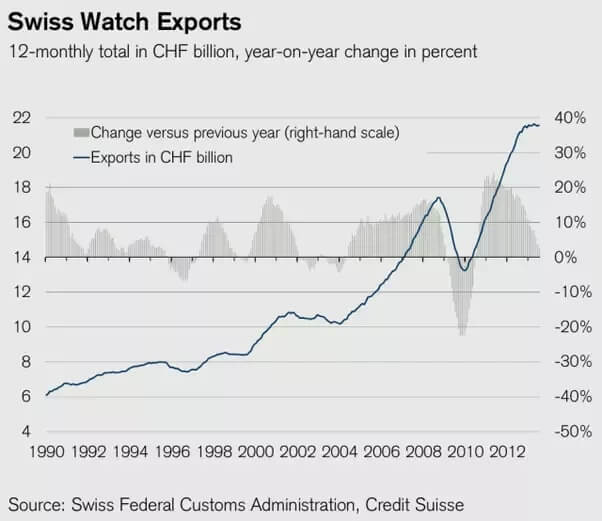

Massive growth in Swiss watch exports since 1990

———————————————————————————————-

———————————————————————————————-

The pros and cons of mass manufacturing

The fat profit margins earned by fragmented and relatively unprofessionally run watch brands attracted the attention of big luxury conglomerates like Richemont and LVMH, and Swatch Group built an empire. Efficiency went up and manufacturing moved in-house.

And China opened up and created a new universe of relatively wealthy potential clients hungry for European luxury brands.

The downside of large-scale manufacturing is that it requires huge investment. The upside is that once you have your production facilities set up, the incremental costs of increasing output, i.e., making more watches, is small.

So the now professionally run watch brands, which were financially motivated to continually increase production (and profits), continually ramped up production. Unsurprisingly, boom and bust cycles followed, but the trend is strongly upward.

So what happened to exclusivity?

Real luxury is exclusive. A luxury is just something you don’t need but would like. Exclusive luxury is something you don’t need but would like, plus is difficult to find (rare) – it’s that relative (to demand) rarity that supports high profit margins.

But the big watch brands were (and generally are now) making mass-market luxury rather than exclusive luxury; however, they have managed to hold on to their juicy profit margins by basically creating a perception of exclusivity and rarity through clever marketing. That and a tight (monopolistic and uncompetitive) control on the prices for which their watches are sold by their retailers.

Collectors/clients: a change in the market

But the real transformation created by the move from exclusive luxury to mass-market luxury is in the clientele: when high-end watches were made in relatively small numbers, they were bought by relatively well-informed collectors who based their decisions on the quality of the watches rather than the effectiveness of the brand’s marketing.

With a mass-market customer base, the majority of watch buyers (present company excluded) is less informed and more influenced by the perceived quality of the brand rather than the quality of a specific watch. They first pick the brand that resonates with them and that they have confidence in, and then a model from the brand that they like.

When my then non-watch-savvy wife first decided that she would like a nice watch, she knew it would be a Breguet before even looking at any Breguets – it was just a question of her finding a model she liked (she chose a Breguet Marine).

Branding becomes more important than the watches as the mass market doesn’t know or care what makes a good watch.

———————————————————————————————-

———————————————————————————————-

Exclusive luxury watches today

In the past, mechanical watches were extremely expensive and very rare because each component was basically custom handmade by an extremely talented artisan.

Then came mass production, which the Swiss watch industry copied from that of the Americans, which made watches affordable for all. Watches became ubiquitous timekeeping tools.

Then the quartz crisis followed by the rebirth of the traditional mechanical watch as a luxury item instead of a tool.

It’s the handcraft that we love about mechanical watches (Rolex, as always, being an exception). It’s the fact that skilled watchmakers have to assemble and regulate a multitude of miniscule high-precision interactive components that links us with the past.

Even space age-looking watches from Urwerk and MB&F have traditional mechanical movements inside that Abraham-Louis Breguet would easily recognize.

While high-precision manufacturing has both significantly reduced the price of each component and made components easily interchangeable, it has also removed much (if not most) of the skills required to be a watchmaker rather than a watch component assembler (as with panel beaters).

Just as today’s panel beaters no longer beat panels but simply assemble interchangeable parts, today’s watchmakers no longer make components but assemble interchangeable parts. Modern watch production is basically just a miniature conveyor-belt assembly line not dissimilar to that of a car factory.

Just round curves, not one internal angle on Patek Philippe’s Caliber 31-260 PS QL powering the otherwise superb Inline Perpetual Calendar

The importance of hand-finishing (finally!)

A modern mechanical watch from big (and most small) brands does not contain as much highly skilled handcraftmanship in its manufacture as the price might infer. And that’s probably not a bad thing: we have accepted the tradeoff in precision mass production over individual handmade parts because it has lowered prices, improved reliability, improved precision, and lowered service and repair costs.

It’s in the beautiful hand-finishing that high-end brands justify their prices (and profit margins). Black-polished flat steel, mirror-polished anglage, guilloche, and three-dimensional-looking Geneva waves are all clear signs that we can see (especially under a loupe) indicating that somebody with world-class skills has worked meticulously with their own hands on our watch.

If only.

Geneva waves

While they look three dimensional, hand-applied Geneva waves are actually flat to the touch – the depth is an illusion created by fine, curved lines on the surface. The first time I ran my finger lightly over Geneva waves Philippe Dufour had made in front of my eyes I was amazed: they looked so deep to the eye, but to the fingertip they didn’t exist.

Three-dimensional-looking (but flat) Geneva waves on the movement of the Philippe Dufour Simplicity

The Geneva waves we see now on the majority of watches by brands are machine made. And they look three dimensional because they are: in most cases, you can feel the lines under your finger.

Guilloche

And then there’s guilloche: high-pressure stamping creates guilloche patterns that are virtually indistinguishable from hand-turned guilloche except under a loupe and knowing what to look for.

Handcrafted guilloche engraves out metal, leaving a razor-sharp ridge that catches the light and captivates the eye. Stamped guilloche doesn’t quite manage to make that sharp ridge, so it doesn’t catch the eye in quite the same way. There’s a reason brands like Breguet trumpet handmade guilloche. It’s expensive (traditional skills and techniques usually are) and produces a better result but is only appreciated by well-informed collectors.

Black polish/mirror polish

Flat steel can be hand polished to such a high degree that it’s called black polish (also known as a mirror polish). The reason for the term “black” is that the surface is so perfectly flat and free of blemishes/scratches that when held at an angle, ALL of the light from its surface is reflected away from the eye so that it appears black. Any miniscule scratch is evident as a bright line of light on an otherwise dark surface.

While high-precision machined steel components might look flat and polished to the naked eye, there are always imperfections from the machining and polishing that catch the light. With black polishing, these irregularities are meticulously polished down with extremely fine paste. However, as the tiny steel particles are polished from the surface, they mix with the fine paste and cause scratches.

Black polished tourbillon bridge with sharp internal angles of the Jean Daniel Nicolas Two-Minute Tourbillon by Mr. Daniel Roth

The art of black polishing is in being able to polish the surface with a sensitive touch and knowing how to avoid mixing the microscopic steel fragments with the even finer paste. The larger the surface, the more exponentially difficult the process is. And you can’t just keep going until you get it right: if you don’t achieve perfection quickly enough, the component becomes too thin to use and you have to start again.

True black polish (not just a nice polish) takes time and immense skill and is a clear indication of a high level of hand-finishing.

Anglage

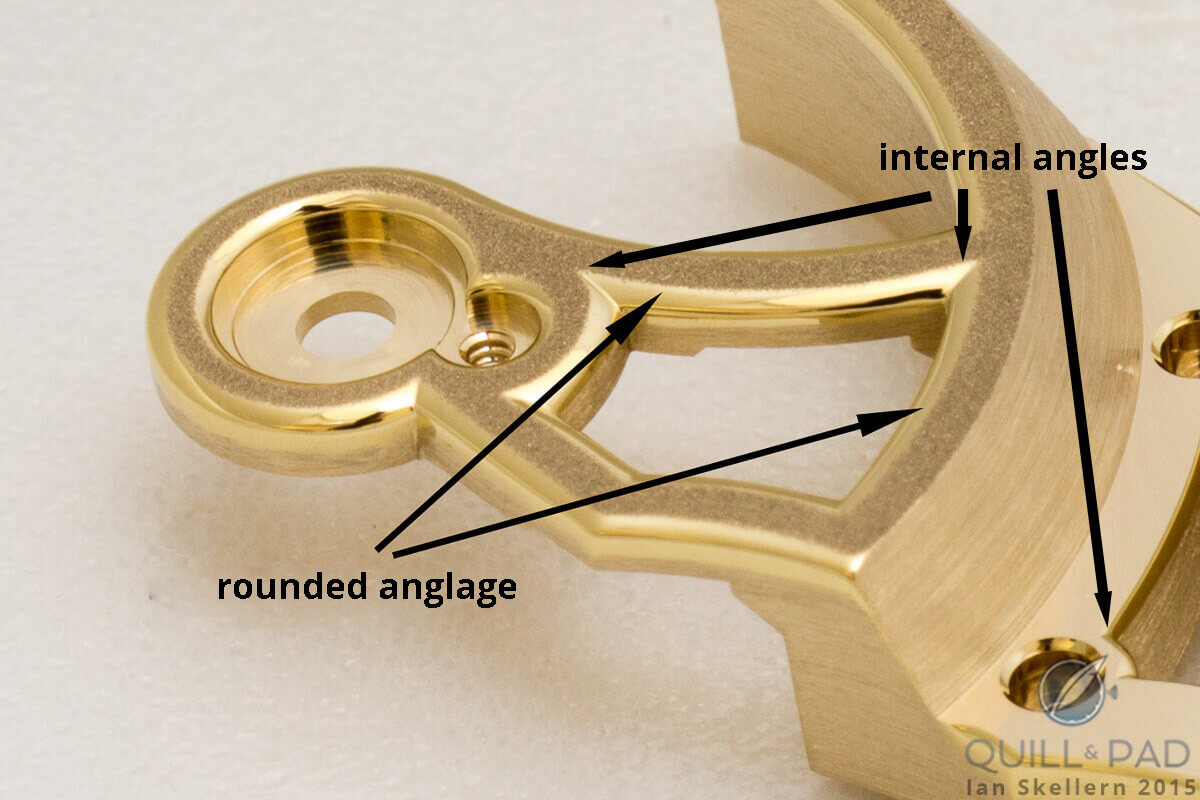

Anglage is a term for a finish, it’s not a description of an angled corner. Anlage is a polished, chamfered edge. Hand-anglage is an extremely labor-intensive art. The edge of a flat steel component is hand-filed to a regular chamfer and then the chamfered edge is hand-polished.

Sharp internal angles in the anglage of an Observatoire by Kari Voutilainen

Hand anglage poses several challenges:

1. Getting the chamfer regular so that it isn’t thicker and thinner along the line.

2. Ensuring that the size of the chamfer on one component is consistent with the chamfer on adjacent or nearby components.

3. Filing and polishing internal angles: with a sharp internal angle, it’s very difficult to file and polish the end of one line without adversely marking the start of the next.

And it’s because those internal angles are so difficult to execute by hand that they are (or, more accurately, were) deliberately included on hand-finished movements to highlight the watchmaker’s skill.

A CNC machine can make a perfect chamfer around a component that can subsequently be either machine-polished or hand-polished, but because the cutting tool is like a small round file, it cannot make a sharp internal corner. At present, that can only be done by hand with a tiny flat file.

Beautiful hand anglage with sharp internal angles of the Akrivia AK-06

And that’s slow and expensive, which is why sharp internal angles have all but disappeared from the movements of most of the big brands – even some of those known (in the past) for their hand finishing.

Now we have nicely finished movements featuring all rounded corners. It’s faster, cheaper, and practically nobody notices. After all, big brands are now selling large numbers of mass-produced watches to the relatively uneducated masses who are buying the brand rather than the watch. And even those educated in fine horology can easily miss noticing the dismissal of hand-anglage.

Movement of the Oscillon l’Instant de Vérité with a multitude of shape internal angles

Big brands are now making beautiful, reliable, and relatively accurate “traditional” mechanical watches, but the hand work many of us value is disappearing. Highly skilled watchmakers and artisans are rare and expensive: there just aren’t enough of them available to churn out the large quantity of nice watches now being sold, and even if more were trained it would increase the price of the watches.

And why bother when nobody seems to have noticed?

Handcrafted rounded anglage with sharp internal angles at Romain Gauthier

Thank God for independents!

Yes, you can still find anglage with sharp internal angles with the big brands, but it’s increasingly rare. If you want and value traditionally hand-finished movements then cast your net past the big brands and seek out the independents.

Superlative hand-finishing, especially anglage, isn’t dead, it’s just more difficult to find: look carefully at the movements of independents such as Philippe Dufour, Kari Voutilainen, Romain Gauthier, Greubel Forsey, Akrivia, John McGonigle/Oileán, Jean Daniel Nicolas by Daniel Roth, and Raul Pagès and you will find beautiful anglage with sharp internal angles galore. Long may they last!

* This article was first published on August 6, 2021 at In Praise of Anglage: Exceptional Hand-Finished Anglage Is Difficult, Slow, And Expensive So The Big Brands Have Given Up And Few Seem To Have Noticed (Or Seem To Care) – Thank God For The Indies!

You may also enjoy:

Does Hand Finishing Matter? A Collector’s View Of Movement Decoration

Why We Are In A Golden Age For Appreciating Superlative Hand-Finishing In Wristwatches

Video: Greubel Forsey And The Art Of High-End Finishing

The Watch That Changed My Life: The Jean Daniel Nicolas Two-Minute Tourbillon By Daniel Roth

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!