Interview with Parmigiani CEO Guido Terreni on the Raison d’Etre of the new Toric: the Art of Dressing

by Carol Besler

Since taking over as CEO of Parmigiani Fleurier in 2021, Guido Terreni has leaned into the brand’s legacy as a maker of classic dress watches at the level of high watchmaking. Not by making a dramatic statement piece but by doubling down on refinement.

Having reintroduced the Tonda, and picking up a GPHG award for it in 2022 (surprisingly in the ladies’ watch category), Terreni turned his attention to the Toric, the golden-ratio proportioned flagship dress watch that was Michel Parmigiani’s first design, the one that gave birth to the brand in 1996.

Parmigiani Toric Chronograph Rattrapante

There are two versions: a rose gold Chronograph Rattrapante with the same high-frequency caliber PF361 found in the Tonda split-seconds; and a rose gold or platinum Petite Seconde.

Parmigiani Toric Petite Seconde in platinum (left) and rose gold

Both use manual movements made of gold. The dials, hands, markers and pin buckles are also made of gold. The dials are hand-grained in a technique that calls for a paste made of cream of tartar, crushed sea salt and silver, mixed with demineralized water.

Every detail has been obsessed over, from the downward-sloping knurled bezel and the beveled dial to the punto-a-mano double-stitched strap.

Guido Terreni, CEO of Parmigiani

Interview with Guido Terreni, CEO of Parmigiani

CB: Tell us about the process of reimagining the Toric and why is this is the right time to reintroduce it?

GT: The relaunch of the brand that we did in 2021 started off with a very important segment of watchmaking, which is a sports-chic watch. That was the priority. We built an assortment and a collection in quite a short amount of time, and it’s complete – though we can still continue to add innovation. It was time to add a second collection that expresses a different type of horology: the dress watch.

We didn’t want Parmigiani to be perceived as a mono product brand because we’re much more than the Tonda, and our aficionados have been asking us to work on reviving the Toric.

CB: How did you differentiate it from the Tonda while keeping the Parmigiani aesthetic?

GT: The dress watch is a totally different world. This segment is a very difficult one to address, because when you exit the metal bracelet watch, you have to be very specific in what kind of emotion you want to generate.

A metal bracelet watch is a monochromatic watch on the body. A dress watch is much more vast in the choices you can have and the materials you can choose, and in the emotion you want to generate. It can be formal, informal, a daily wear or something for more evening attire.

To do a watch like this, you first have to answer to the question, what is a dress watch today? And looking at the watch industry doesn’t help because the watch industry is very conservative and it’s very stuck in the way that we used to dress decades ago. That’s because of its origins in Geneva, which is protestant Calvinism. It’s an expression of an elegance that is very formal and it’s … a bit stiff.

It’s very elegant, but it has certain specific rules. And these rules go back 200 years to the industrial revolution, thanks to the bourgeoisie who brought the suit into menswear.

Parmigiani Toric Petite Seconde on the wrist

The suit was and is a uniform, a civil uniform that was essentially black and white. At first, it was worn only by the aristocracy, and it was very black and white – it was the tuxedo, and the tuxedo was worn not like you would wear it today, for special occasions like a gala dinner. It was what affluent aristocrats wore to the theater, to friend’s house, or just for dinner.

Black was a color that was the most difficult to wear because dying techniques of the time were not steadfast. After a couple of washings, it would become gray. So only the rich could wear black.

And the white shirt comes into the picture together with the black suit. During the Industrial Revolution, the suit was worn by the new bourgeoisie. It was adopted by entrepreneurs who built their factories, their businesses.

Wearing the suit made a statement that said, ‘I built my own wealth and now I have to be credible and consistent.’ So they wore the black suit. It expressed that, yes, you are working but you’re working intellectually, you’re not working in the dust or in the factory.

CB: So with the rise of the suit, the rise of the pocket watch.

GT: Yes, and they had to be extremely decorated. Even the bourgoiesie wanted to have one, to look like the lords and the nobility. And then, when the watch came out of the pocket at the beginning of the last century, and was put on the wrist, it had to fit in with that attire.

As I said, Geneva, the capital watchmaking, was very Calvinist, so you had dress watches that were extremely sober, with extremely subtle white dials to match the shirt, and black glossy straps to match the shiny shoes.

And you had gold or platinum as a metal.

CB: With few variations.

GT: The only nuances that you had were through the architecture of the case. You can see the influence of Art Deco in the ’30s and ’40s on certain watches, on the indexes and on the case. But in the end, the aesthetic codes were those of that old world. After the Second World War, you abandoned the tuxedo as the rule and you still have it very often, but you can wear gray, you can wear other colors.

So you started seeing brown straps, maybe blue dials … but that was the maximum that you could see on a dress watch.

And then the industry of watchmaking had a quartz crisis, and the industry of menswear had his own crisis, which is thanks to the Americans because you have the new economy coming up with entrepreneurs of the dot-com economy who threw away the suit, and threw away the watch with the suit, started wearing casual sneakers … you see very fortunate people from Silicon Valley going to work without a suit, going to important meetings dressed in a very casual way.

And you lose this culture of dressing … and at the same time, you lose the sensitivity of what a beautiful mechanical watch is.

Parmigiani Toric Chronograph Rattrapante in rose gold

CB: Then mechanical watchmaking was revived in the late 1990s.

GT: There has been a renaissance of the mechanical world in watchmaking since the year 2000, people rediscovered, high-end watchmaking and the business of high end watchmaking has blossomed since then. And now, 20 years later, we are seeing a rediscovery of sartorialism, which is booming as a business.

Gentlemen in their thirties are rediscovering how beautiful it is to dress well. Not to dress formally, but to dress well. And that means a tailored suit, which is not for a season or two – you’re not fashion victim, waiting to see what a designer comes up and you have to put the logo of the brand.

No, it’s your personal style that you establish, and you build up your wardrobe to express who you are, with taste and with the knowledge of what the nice suit is or what a trouser can be. You may not wear it with a tie, or a buttoned shirt.

It can be with a T-shirt, it can be with sneakers. It’s a more informal way of dressing well – and black is not anymore in the picture. So this is a trend that is picking up worldwide, brought mainly from a younger generation. I think films like “Kingsman,” for example, had a big role in expressing that sartorialism in a way that is fascinating for a younger public that looks up to that way of elegance, that looks up to these heroes, and when the protagonist ends up dressing like them, he’s so sexy.

So, when it comes to watches, what do you put on the wrist of these people? You put this: [presents the Toric Petite Seconde].

Parmigiani Toric Petite Seconde dial details

CB: When you put it that way, it seems almost like a tool watch, because it has such a specific purpose.

GT: It makes sense. First of all, you see the style and it fits in with everything. The new sartorialists are interested in the authenticity of the product. They respect the traditions of sartorialism, and that extends to watchmaking. It starts with the movement. For the Toric, we’re using only manually wound movements.

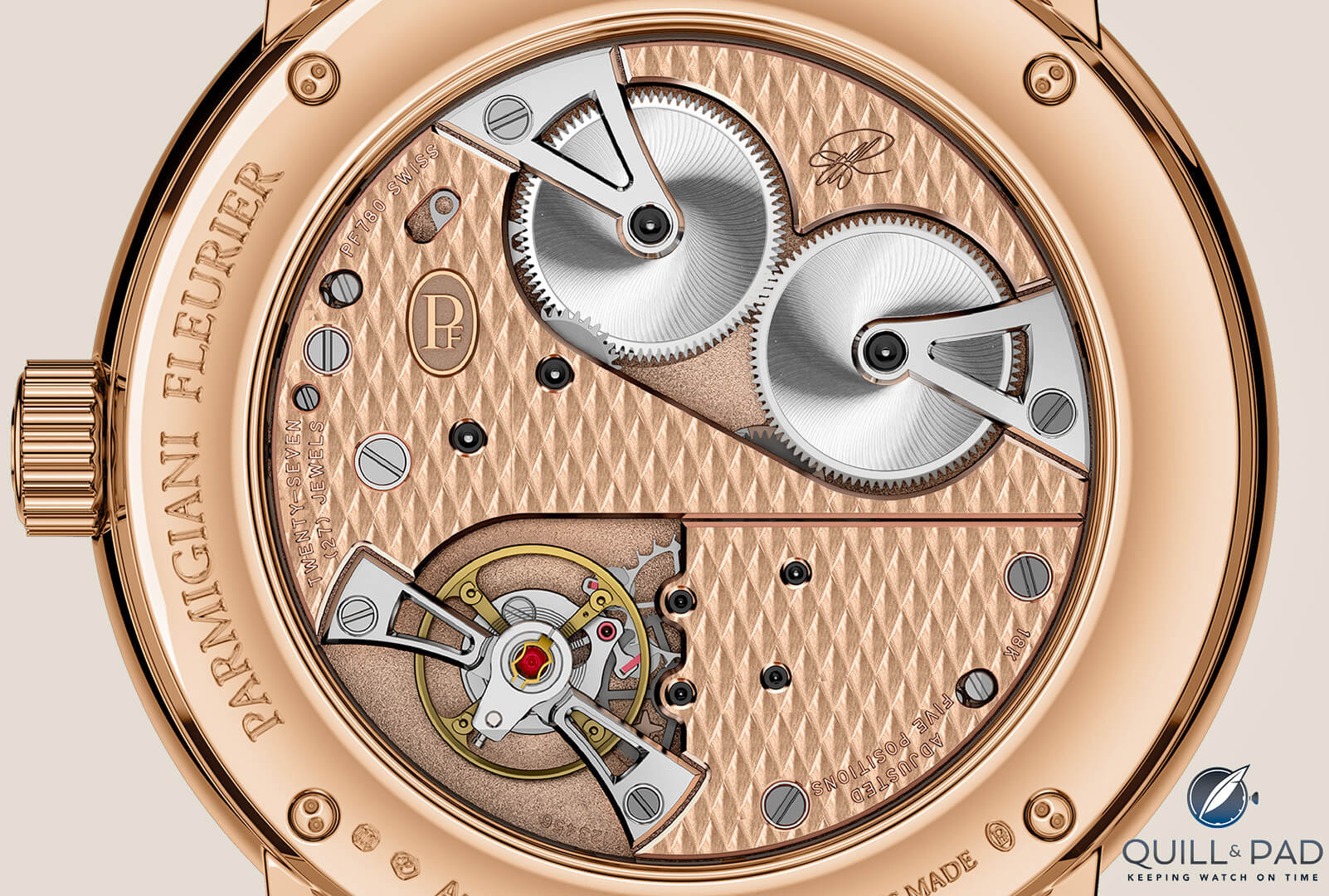

Parmigiani Caliber PF780 visible through the display back of the Toric Petite Seconde

That’s the most beautiful way to do a mechanical watch – you don’t have a rotor blocking the beautiful finishings.

Parmigiani Caliber PF361 powers the Toric Chronograph Rattrapante

And only gold movements. Gold reflects the light in a much deeper way. It’s extremely beautiful to look at a gold movement and it’s very rare to have it in the industry. We’ll also only have gold dials that are done very subtly because this aesthetic is done in a way that is not in your face. Every detail is there to convey a certain emotion.

Parmigiani Toric Petite Seconde

CB: Tell us about the grained finish on the dial, with the formula of cream of tartar, crushed sea salt and silver.

GT: It’s done by hand, with brushes. Michel [Parmigiani] spent one full day in the dial manufacturer to teach this artisanal technique. It’s done by brushing the gold with the paste. Nine watches out of 10 that are grained today are done by laser, but this is done by hand. It gives you a certain patina, and each one is different.

Depending on the thickness of the brush … the thicker it is, the smaller the grains are. It has to be done just right, because we wanted the grain to be there, but not-there. It mustn’t be invasive to the eye. Once you finish it, you drill out the outlining gold borders around the subdials.

CB: The colors are very neutral.

GT: Yes, it’s the chromatic universe of Le Corbusier. The Toric can be worn with black or any color. The straps are light green or beige hand-stitched nubuck alligator. And the stitching comes from the sartorial approach. It’s a stitching that you find on the most fine suits. It’s called punto mano and originates from Naples. Tailoring “punto” means hand point.

And then you have a pin buckle because when you want to admire the movement, you don’t want to have the blade of a folding clasp in the middle of your eyes.

CB: So, you’re extending the aesthetic limits of the traditional dress watch with a contemporary approach, including different colors, but your techniques are still very much in line with traditional high watchmaking.

GT: Yes, but it’s very subtle. You only have a few millimeters to make something happen on a watch dial, and the details must not be in your face. They must be subtle because the brand is subtle. You have to be true to the values of the brand. There is a deep cultural tradition of why things are done with these techniques … with the understatement and the lack of ostentation of the brand.

These values are the basis of every decision. But as Michel says, restoration and tradition are not a cage. You cannot be stuck in the past. You have to use that tradition to move forward, to continue to evolve.

Twenty, 30 years ago, brands discovered that they had to make big, big business, and one way to do that was to keep the same creativity going for the longest amount of time. So you start re-editing your past, instead of creating new things. And that’s where it becomes boring.

Our clients are looking for non-homologated aesthetics to have a personal choice on their wrist. And it doesn’t matter if nobody recognizes it because they are beyond social recognition when they purchase Parmigiani. They have taken that mature step where they understand that what’s important is not what other people think is cool, but what you think is cool.

And when you are in that moment, you are open to your freedom of choices and you are going for a personal luxury that is private.

There are many people who share these values and view the brand as prestigious. It was easy to reactivate those who knew the brand. And now there are more people knowing us and word of mouth that is spreading and helping us interact with more clients. The fact that this is an additional collection, many clients who have already bought the Tonda, I’m sure they will be interested in the Toric.

Parmigiani Toric Petite Seconde in platinum

CB: Will you increase production?

GT: Not this year. We don’t want to increase because we grew very much since my arrival. We passed from the worst year to the best year from 2020 to 2023. And I think it’s important to grow at a pre-set rhythm.

CB: You grew in terms of production or in terms of revenue?

GT: We grew five times in revenues and three times in production. But now, I mean, the market is different. There are too many watches all around. The bubble of the flippers is finally reducing. But this is an additional channel that has additional product. Not really Parmigiani because it’s not, the quantities are not there to have entered in that channel, but there is too much product around. So we are obviously affected by that.

For more information, please visit www.parmigiani.com/en/watches/toric-petite-seconde-rose-gold-sand-gold/ and/or www.parmigiani.com/en/watches/toric-chronograph-rattrapante-rose-gold-natural-umber/

Quick facts: Parmigiani Toric Petite Seconde

Functions: hours, minutes, small seconds

Case: 18 carat rose gold or platinum

Dimensions: 40.6 mm x 8.8 mm

Water resistance: 30 m

Movement: Caliber PF780, 4 Hz, 18 carat gold

Power reserve: 60 hours

Strap: alligator

Water resistance: 30 meters

Price: 45,000 Swiss francs in gold

Quick facts: Parmigiani Toric Chronograph Rattrapante

Functions: hours, minutes seconds, flyback chronograph

Case: 18 carat rose gold

Dimensions: 42.5 mm x 14.4 mm

Movement: Caliber PF361, 5 Hz, , 18 carat gold, double column wheel

Power reserve: 65 hours

Strap: alligator

Water resistance: 30 meters

Price: 135,00 Swiss francs

You might also enjoy:

Parmigiani Fleurier Tonda PF Split-Seconds Chronograph Reviewed by Tim Mosso

Parmigiani Fleurier Tonda PF GMT Rattrapante: A Design Nerd’s Favorite Travel Watch

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!