“Gravity . . . is working against me; and gravity . . . wants to bring me down.”

Oops, I probably shouldn’t quote John Mayer since he has a financial interest in a certain online watch website that will go unnamed. Still, John Mayer’s song “Gravity” holds a special place from my time as a swing and ballroom dancer in college (you read that right). Every spring our university would hold an event in which dancers from all the student classes, clubs, and the university dance team would perform.

During my first year participating, my friend’s team used that song for a choreographed number, which I found incredibly moving. Ever since, when I hear the word “gravity” I immediately sing the opening phrase. Even when I am reading about or discussing astronomy and quantum physics, when “gravity” comes up it is the first thing in my brain.

So while I am humming John Mayer, I am also discovering that scientists still don’t technically know what gravity is. We know how to measure it, we know generally how it functions, and we have figured out some of the mysteries of the universe simply by calculating its effects. But we still have fundamentally no clue what gravity is and what causes it.

Attempts to reconcile the theory of gravity with quantum physics and develop a unified theory of everything explaining all the fundamental forces of nature has as of yet remained elusive.

We may know about the Higgs field, the quantum field that gives matter its mass, and the Higgs boson, a particle that creates the Higgs field, but that’s not enough to explain gravity and why it works like it does.

So for now, gravity remains both a fundamental force of nature and a song that will never leave my head, more strongly linked than gravity and the strong nuclear force.

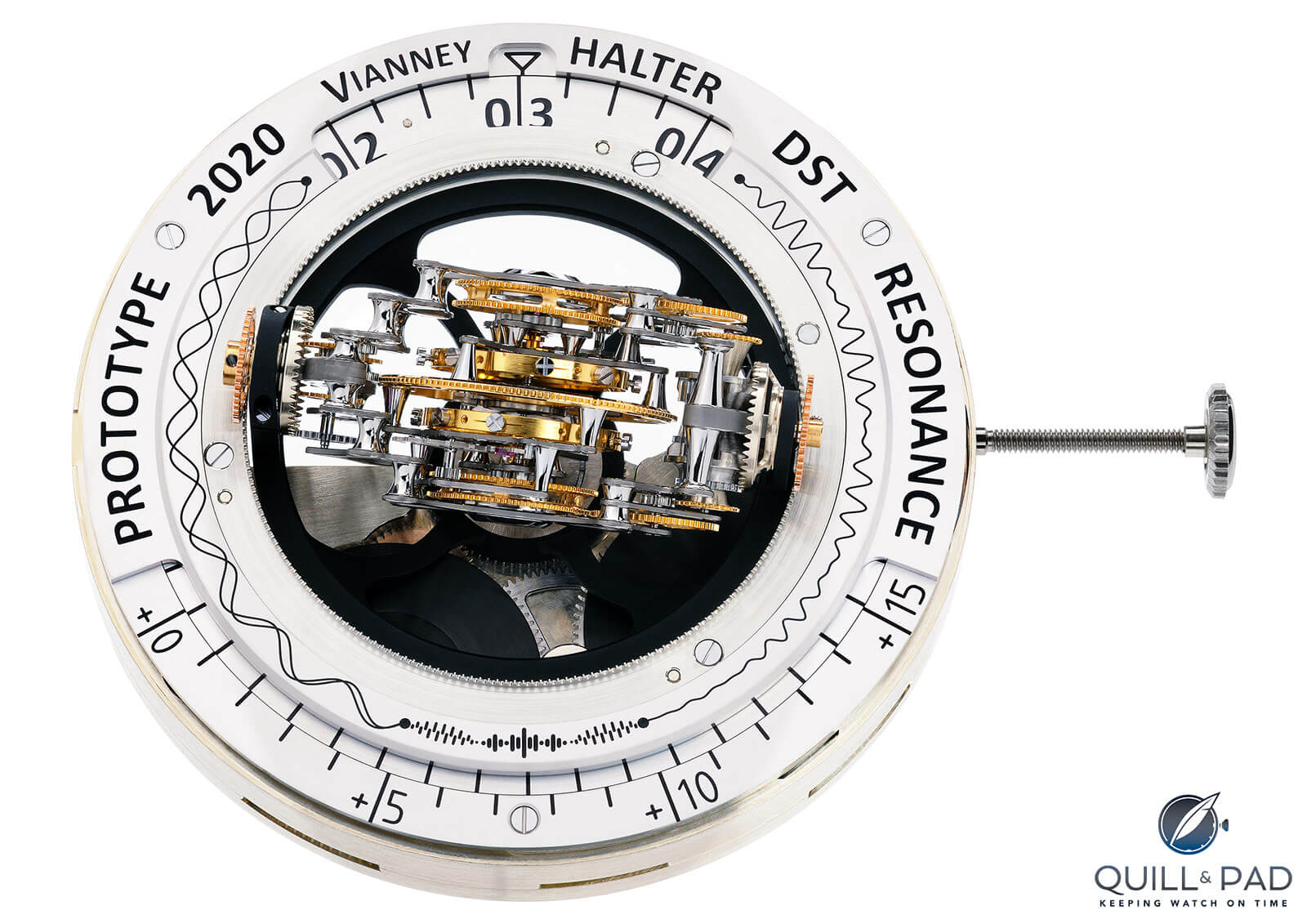

Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance Prototype (photo courtesy Vianney Halter/Guy Lucas de Peslouan)

But we don’t need to know exactly what gravity is to be inspired by it, as Vianney Halter was in 2015 when gravitational waves were confirmed for the first time. The news reignited a project that had been slowly burning in him since 1996.

After 20 years of research, experimentation, and invention, gravitational waves kicked Halter into high gear to finally move ahead. The result was revealed on January 5, 2021 (good job waiting until after 2020) when Halter introduced the Deep Space Resonance prototype.

And it was definitely worth the wait.

Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance prototype

I’ll dig into the details below, but first want to explain why this watch is the most incredible thing to happen in 2021.

For one, we are only two weeks into January, so it has a head start for 2021. But more importantly, the Deep Space Resonance is a brand-new entry into the field of resonance watches, joining an extremely small club of watchmakers having created resonance wristwatches.

The concept was applied to Halter’s popular Deep Space format and is the culmination of 24 years of (non-continuous) development to realize a dream the independent watchmaker has had for a significant portion of his adult life.

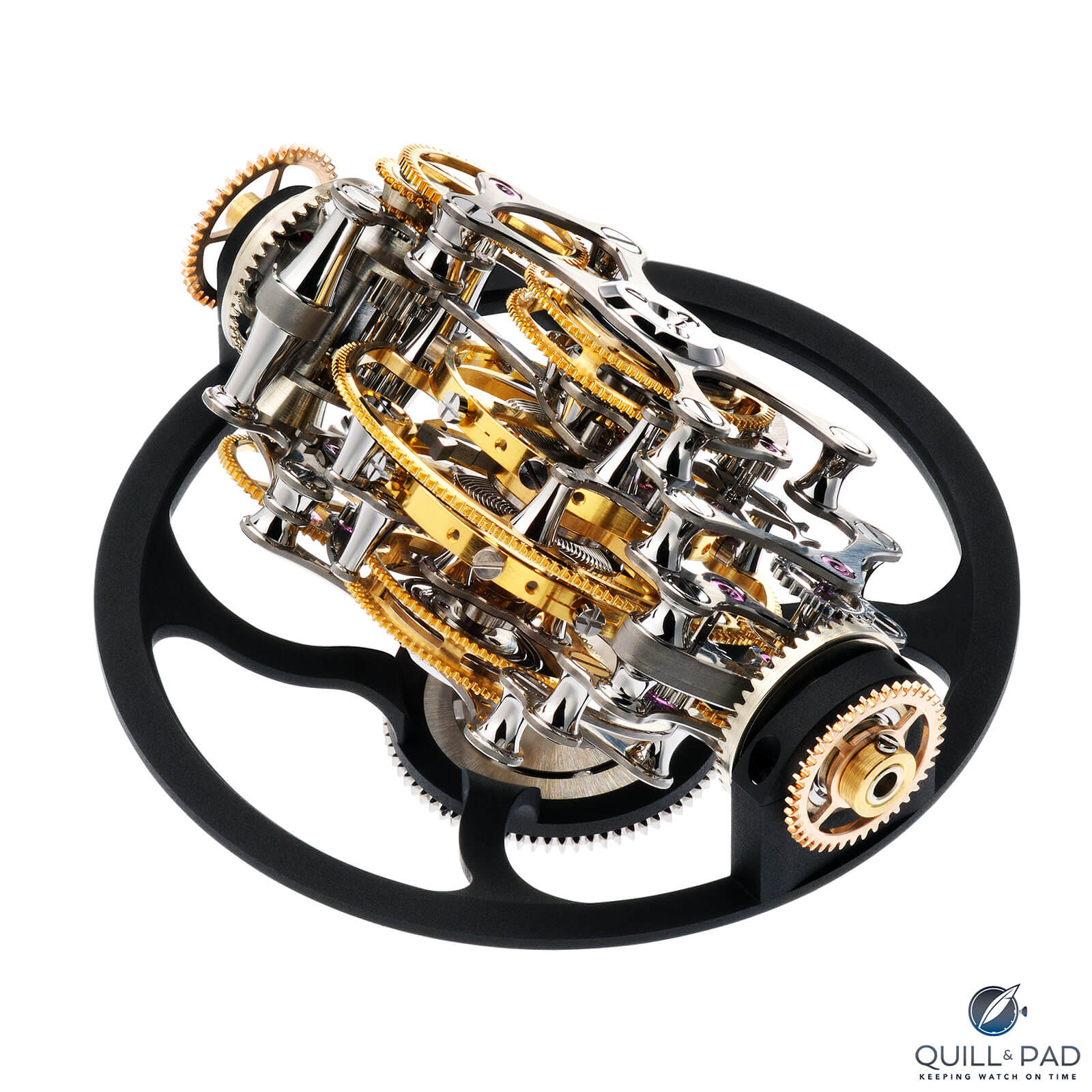

The basic description of Deep Space Resonance includes a dual balance, resonance, a triple-axis tourbillon making one revolution of the outer cage every 30 minutes, and displaying hours via a wandering hour ring and minutes on a vernier scale. All housed under a massive sapphire crystal dome.

Deep Space Tourbillon by Vianney Halter

Deep Space Resonance looks visually related to the Deep Space Tourbillon of 2014, but the resonance regulator at its heart is so much more complicated and incredible that it took Halter 24 years on and off to create it.

In a similar vein as Halter’s Deep Space Tourbillon, Deep Space Resonance features a large central triple-axis tourbillon mechanism occupying most of the watch face. This mechanism alone contains 371 individual parts and is a six-layer smorgasbord of gears, pillars, and bridges, all with a healthy serving of ingenuity in the goal of a resonance tourbillon.

Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance: resonance

Before we move on to discuss all the delicious details of this mechanical birthday cake of horology, let’s revisit the concept of resonance – and, more specifically, acoustic resonance.

In a past article or two, I have discussed how resonance is the phenomenon of utilizing two (or more) oscillating systems affecting each other’s rates so that they oscillate in unison. The phenomenon is technically how all watches function as the balance wheel and spring is already resonant mechanism.

But in horology there is a subcategory of resonance specifically referring to two balance wheels assembled in one movement so that they resonate with each other, their rates becoming linked and simultaneous.

The most recent and famous examples of resonant watches are the Armin Strom Mirrored Force Resonance, the F.P. Journe Chronomètre à Résonance, and the Haldimann H2 Flying Resonance, all three achieving the resonance phenomenon in different ways.

The idea of resonance is very old, and Halter (and the others in this small club) were technically inspired by Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747-1823) and Antide Janvier (1751-1835), the pioneers of horological resonance. Still, each watchmaker found a unique way to create the phenomenon, with Journe being the truest to tradition and Armin Strom having the most modern take.

Halter’s research led him to understand that the original Breguet design likely relied on fluid dynamics as a primary resonance mechanism, meaning that the two balances needed to be very close to each other so that the air friction and turbulence would create drag on the nearly touching balance wheels, inducing the resonance phenomenon.

I cannot verify that the Breguet and Journe examples rely on this mechanism, but Halter is convinced this is the case. He demonstrated that his design does not use fluid dynamics, but the mechanical acoustic properties of the structure, after he tested a bench prototype inside a vacuum chamber to confirm that resonance occurred.

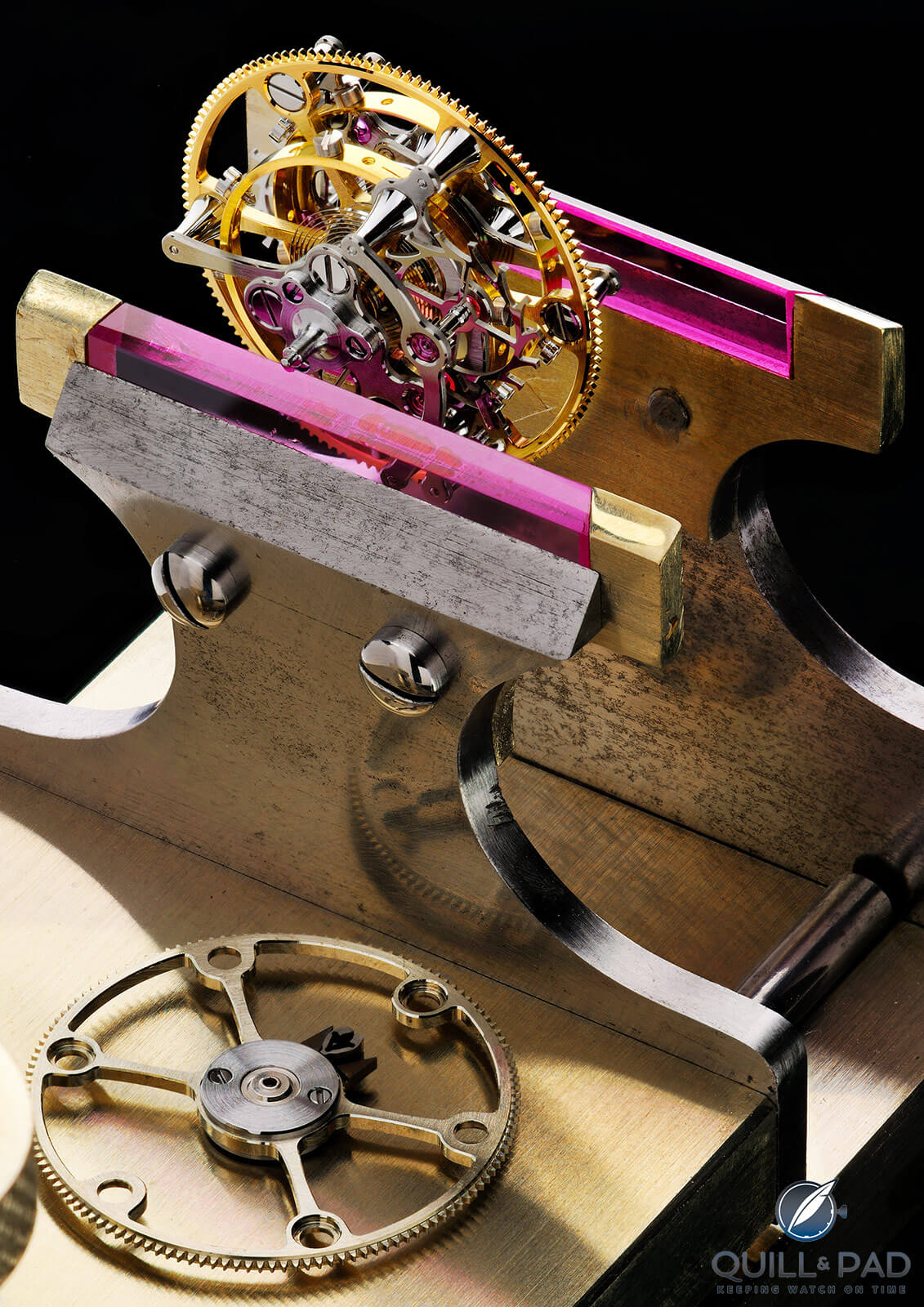

Fine-tuning the tourbillon cage of the Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance prototype (photo courtesy Vianney Halter/Guy Lucas de Peslouan)

His test prototype functioned as expected so he ruled out fluid dynamics, confirming that his design operated with acoustic/vibrational resonance.

This is where vibrational waves of energy are transferred through the structure holding each oscillator and impart drag on the opposite oscillator. I described this in much more detail in my piece Understanding Resonance, Featuring The F.P. Journe Chronomètre à Résonance, Armin Strom Mirrored Force Resonance, And Haldimann H2 Flying Resonance, but the basic idea functions sort of like a spring but with rigid materials.

As one oscillator vibrates, it sends a small amount of that vibration to the other oscillator, which modifies its rate. Eventually the two settle into a shared average and more stable rate.

How the Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance does its trick

The design of Halter’s triple-axis tourbillon with paired resonating balance wheels is straightforward, functioning similarly to the Haldimann H2 Flying Resonance, but in a very different in form.

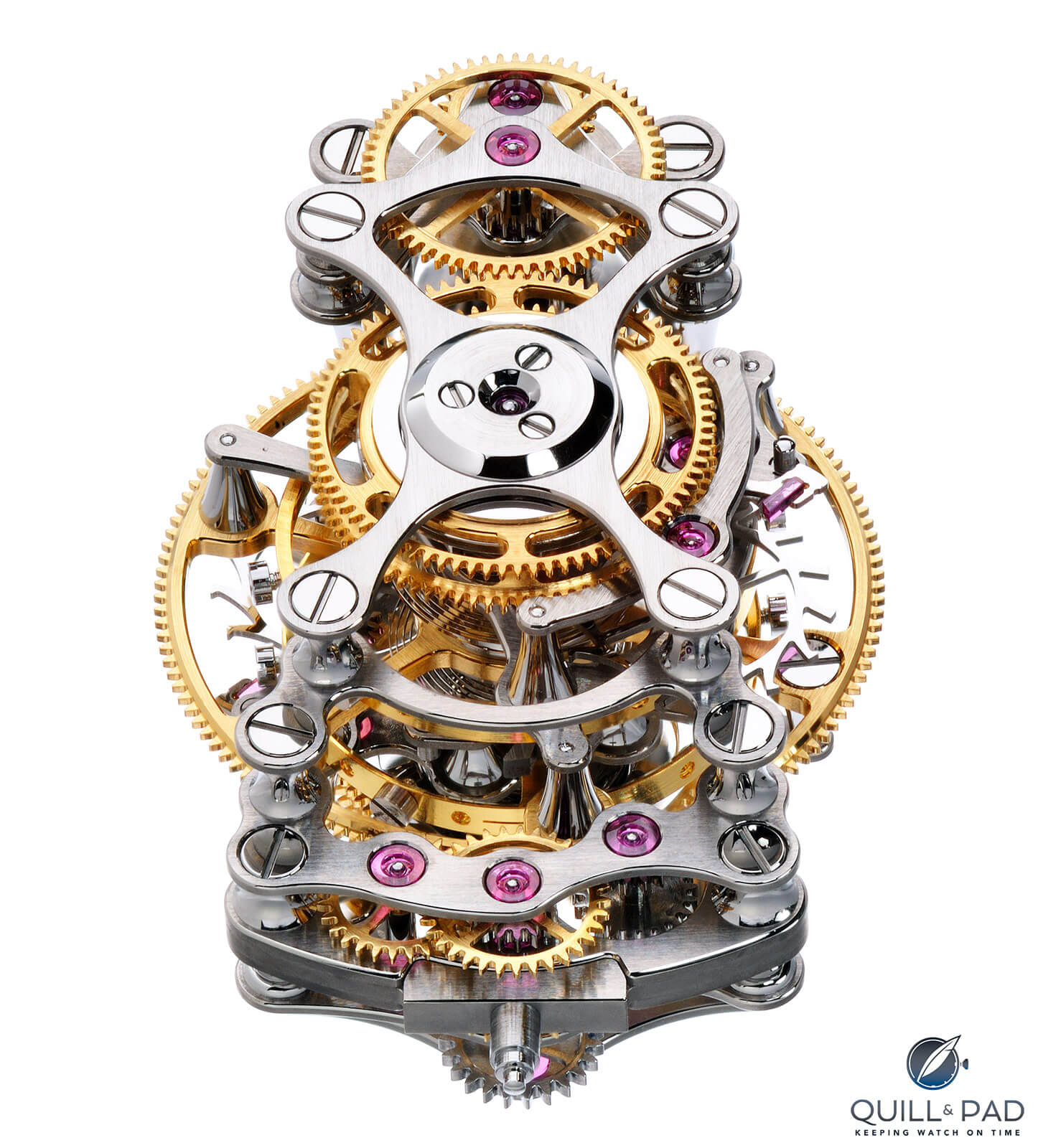

Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance’s triple-axis tourbillon regulator (photo courtesy Vianney Halter/Guy Lucas de Peslouan)

The two balance wheels are mounted coaxially to the same central wheel, just on opposite sides. This keeps them as close as possible, allowing for simple mechanical coupling. The hairspring studs for both balances are mounted to a shared structure attached to the central wheel, which was specifically designed to reduce the distance between the oscillators and maximize transmission of their vibrational energy.

The vibrational waves of the hairspring and balance wheel push and pull in very tiny amounts on the hairspring stud, which imparts a small amount of vibrational energy into the other stud. This works in both directions and, if the balance wheels are close enough in rate, size, and amplitude, they will eventually enter a resonant relationship.

The balance wheels can oscillate together, both rotating in the same direction and at the same speed, or they can oscillate 180 degrees out of phase, meaning they rotate in opposite directions. But both reach the extent of their rotation at the same moment.

Each direction is a stable resonant system and, depending on how each balance wheel begins its motion after coming to a rest, determines if they resonate in the same direction or 180 degrees out of phase.

This setup is similar to the Haldimann H2 Flying Resonance in that the tourbillon has two balance wheels mounted on a cage next to each other, with their hairspring studs attached to a special bridge between the two that provides an effective path for the vibrations of the balance wheels to interact.

This differs from the F.P. Journe Chronomètre à Résonance, which relies on balance wheels mounted very close to each other. The Armin Strom Mirrored Force Resonance avoids the hairspring stud mounted to a rigid block; instead both hairspring studs are mounted to a third spring that very efficiently transfers vibrations.

But beyond the physics, Deep Space Resonance is a triple-caged tourbillon, but with more cages due to its extra balance wheel.

The Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance regulator (photo courtesy Vianney Halter/Guy Lucas de Peslouan)

Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance: details matter

As previously mentioned, the full tourbillon assembly has a whopping 371 components, including a staggering 42 individual pillars to support each bridge plate. This design choice is not random; it is inspired by a marine chronometer that Halter purchased in 2018 made in 1840 by Achille Benoit (1804-1895).

A work of mechanical genius in its own right, the central mechanism had a unique set of steel pillars unlike the more typical brass pillars found on other clock mechanisms. The aesthetic hooked Halter, and he incorporated it into the final tourbillon design.

That tourbillon (barring the resonance architecture) is fairly traditional in design. Each balance oscillates at 3 Hz (21,600 vph) and uses a typical lever escapement. The inner dual-sided cage rotates once every 60 seconds while the middle cage rolls on a horizontal axis once every six minutes, with a full rotation of the outer cage occurring every 30 minutes.

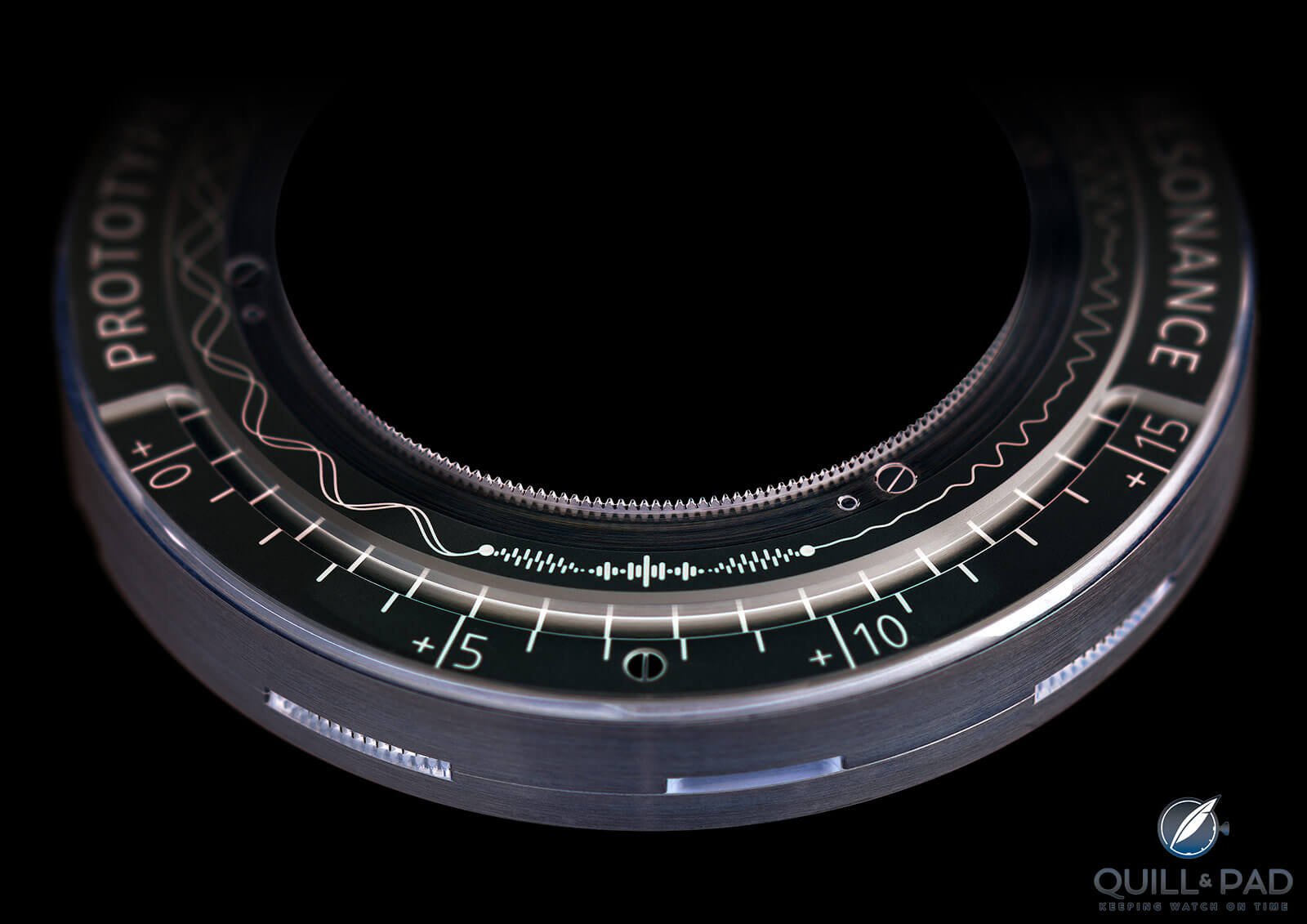

This is where Deep Space Resonance departs from most watches. That outer cage then drives a ring around the periphery of the dial that looks fairly ordinary at first glance. While the hour ring is simple, rotating once every 12 hours and indicating the time using a small triangle pointer at 12 o’clock, the minutes are a different beast.

Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance vernier scale for minutes (photo courtesy Vianney Halter/Guy Lucas de Peslouan)

The minutes are displayed on a vernier scale spanning the bottom third of the dial, showing minutes from left to right with 0 to +15 markers for each minute in between. Where it gets interesting is that the ring that moves to show the passage of time has nothing but small hashmarks, with no numbers or anything extra, just lines.

The time is read by combining the hour ring, which has three additional hashmarks between the hour to separate out the quarters, and the minute ring.

Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance Prototype (photo courtesy Vianney Halter/Guy Lucas de Peslouan)

But on the bottom, the hashmarks don’t evenly match the lines for minutes, instead they are all (deliberately) a little off. Each minute that passes moves the ring a little bit counterclockwise; one of the marks aligns with a minute mark before moving slightly onward, progressing from left to right. It only moves one full mark forward every 15 minutes as each mark aligns with a minute marker. This is how a vernier scale functions.

As it cycles through all 15 minutes, the first mark that aligned with zero will now be closing in on the one-minute mark and a new line will be approaching the zero again. This means it takes four hours for the first mark to rotate past all the 15-minute marks and become hidden behind the cover plate again.

This vernier method of reading off the minutes and adding them to the quarters is not intuitive, but you should get used to it with enough wrist time.

Along the ring separating the tourbillon carriage from the time rings we find a visual representation of what an acoustic signal would look like as two separate wave forms slowly adjust into resonance (on the left) and what a vibration frequency can look like as it modulates up and down.

Aesthetically the dial is rather tool-like and utilitarian feeling, like a scientific instrument in a lab (a vernier caliper was basically the inspiration), but remember that this is only the prototype. Halter has said there will be aesthetic and mechanical changes and alterations for the production model, which is planned to launch in the third quarter of 2021.

Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance prototype with multi-tourbillon regulator and dial (photo courtesy Vianney Halter/Guy Lucas de Peslouan)

Deep Space Resonance isn’t limited in number but is limited by production capability. Only two will be produced each year, making this one extremely rare watch. Given its anticipated retail price of 860,000 Swiss francs, it will have a very small market of collectors, but I would not be at all surprised if there is already a waiting list..

The success of the Deep Space Tourbillon motivated Halter to use that same design language for the Deep Space Resonance, and I am ecstatic that this design will live on in a second model as the Deep Space Tourbillon was my favorite Halter piece (and that is saying something) up until this new model.

Vianney Halter may not produce a wild new design every year (or decade), but when he does release something new it is always worth the wait.

It’s also cosmic luck that scientists discovered gravitational waves when they did and inspired and encouraged Halter to finish the Deep Space Resonance. After years of hard work, business distractions, and the fluctuation of markets and everyday life, Halter was able to produce something almost perfectly encapsulating why I love mechanical watchmaking.

Like many of my other favorite watches, Deep Space Resonance is an horological machine that happens to tell time, but is more a mechanical marvel inspiring future watchmakers to stretch what is possible.

Unlike Deep Space Resonance, gravity is working against me, so let’s break this bad boy down!

- Wowza Factor * 9.95 Nearly a perfect score; whenever Vianney Halter releases something new it is bound to make people stop and exclaim wowza!

- Late Night Lust Appeal * 99.5» 975.761m/s2 A dual-balance resonant system within a triple-axis tourbillon all under a huge sapphire crystal dome, yes please!

- M.G.R. * 71.5 Another nearly perfect score, the movement inside this piece has few rivals. A hallmark of Vianney Halter is making mechanical creations that are incredibly geeky!

- Added-Functionitis * N/A It’s actually been a little while since I reviewed a basic, time-only watch and, like most I review, they are time-only simply because the rest of it is so darn complicated! Still, you can skip the Gotta-HAVE-That cream even though I definitely do gotta have that!

- Ouch Outline * 11.85 Stepping on a Lego with socks on! A nearly perfect score reminds me of what it is like to step on a Lego with socks on: it is almost as painful as barefoot, but there is a very small amount of relief, and I’d gladly make that trade if it meant some time with this bad boy!

- Mermaid Moment * Did you say resonance in a triple-axis tourbillon?! The triple-axis tourbillon is the mechanism that first got me hooked on watches and combining it with a resonance mechanism is magical!

- Awesome Total * 1,000 Start with the number of parts in the triple-axis tourbillon assembly (371) and multiply by the frequency of the balance in Hz (3), then subtract the caliber number (113) for a perfectly round awesome total!

For more information, please visit www.vianney-halter.com.

Quick Facts Vianney Halter Deep Space Resonance

Case: 46 x 20 mm, titanium

Movement: manual wind Caliber VH 113, 65 hours power reserve, 3 Hz/21,600 vph frequency, twin-balance resonance in triple-axis tourbillon

Functions: hours, minutes

Limitation: two pieces per year

Price: 860,000 Swiss francs

You may also enjoy:

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

I love Vianney Halter’s work. He is truly one of the greatest watchmakers of all time (as is Beat Haldimann), and this latest creation is extremely impressive. However, Haldimann’s Flying Resonance H2, in my view, is just as great an achievement. The reason is simple. The H2 manages to achieve its magic (the first ever resonance watch with a remontoire!) in a 40mm case that is relatively thin and very wearable. In other words, the H2 is a complicated and innovative watch with classic proportions. Indeed, its (complexity*innovation)/volume efficiency rating is much higher. This is even more remarkable when considering that it was released about 16 years ago in 2005! That cannot be said of the Deep Space Resonance. Even so, I still love it! Both watches are among the greatest achievements in horological history!