Hearing Is Believing: Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie And The Science Of Sound

by Ian Skellern

If a tree falls in the forest and there is nobody there to hear it, does it make a sound? That’s not a trick question; the answer is no.

“Sound” is a creation of the brain to represent a specific range of vibrations around 20 to 20,000 Hz. Vibrations in the air (as well as in liquids and solids) become sound when they are heard; until then they are just a small segment of the largely silent cacophony of vibrations in the air.

What we hear is not the sound vibrating our eardrums, but what our brain thinks we should be hearing based on a large number of factors, our ears being just one.

The human ear is particularly sensitive to frequencies around 3,500-4,000 Hz, which is where most human speech takes place as well as the sounds a baby makes. Our brains amplify frequencies in this range.

Sound is complicated, very complicated. We hear high frequencies better than low frequencies. Lower frequencies tend to create more of sense of “feeling” than hearing. Higher pitched sounds (high frequencies) seem louder – in our heads – than lower pitched sounds of the same intensity.

A 60 dB sound with a frequency of 1,000 Hz sounds louder to us than a 60 dB sound with a frequency of 500 Hz – 60 dB being the sound level of normal conversation.

When we hear frequencies around 3,500 Hz (human voice) they will tend to sound 10 to 20 dB louder than other frequencies.

This is because sounds are vibrations in the air as interpreted by our brains; and sounds – like colors – are subjective. To create the sounds that we silently hear in our heads, our brains take the vibrations in the air that are picked up by ears and add that to other information, including memories, context, previous experience, and expected sounds.

Like a full-time sound engineer, our brains are continually moving the sliders up and down, boosting the volume of some frequencies in places, lowering volumes in others, fading out unimportant sounds altogether, and ramping the volume up if keywords (like your name) are triggered.

We do not hear like a recorder any more than we see like a camera: what we hear is a construct. Meaning you are right, ladies: he isn’t listening to you while reading the paper.

We even hear “ghost” sounds as our brains recreate non-existent frequencies that it expects to hear.

Widely appreciated music usually follows elegant mechanical rules: a great composer writes the mathematical formula for a piece of great music. But those mathematical notations on the page only become majestic sounds in the hands of a virtuoso conductor, one that doesn’t only know how to get the best performance out of the orchestra as a whole, but knows how to use the sounds to maximum effect in amplifying the filtering of the brain so as not only to generate information, but strong emotion as well.

Wikipedia states that, “Pitch is a perceptual property of sounds that allows their ordering on a frequency-related scale . . . ” and “Pitch may be quantified as a frequency, but pitch is not a purely objective physical property; it is a subjective psycho-acoustical attribute of sound.”

In the world of minute repeaters, the watchmaker has generally played the role of the conductor, who tunes the noise the repeater creates into the most pleasing form possible. Over the last few years, the watchmaker has been increasingly aided scientifically and electronically by machines displaying volume (though not perceived volume) and frequency (though not pitch).

Guilo Papi of APRP demonstrating the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie on his own wrist (the blue is a protective tape); the chiming could be easily heard across the busy workshop

What the Supersonnerie does is ramp up both the science and the musicality, taking them to a whole new level, and making it a fitting watch to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of its developer, Renaud & Papi (now Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi / APRP), which began operation in 1986.

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie

It’s because sound is so complicated that it took Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi (APRP) a full eight years of researching perception of the ear and brain and developing a watch (not just a movement) showcasing the results of that work.

The sound of a minute repeater is caused by a tiny hammer hitting a small gong made from a coil of steel wire. The gong vibrates, which makes the air around it inside the watch case vibrate. Acoustically ideal would be if there were holes in the case for the vibrations to escape unhindered into the air, thereby reaching our ears as loudly as possible.

A close look at the dial side of the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie

But the problem with that hypothetical setup is that any holes in the case allowing vibrations in the air to escape with minimal hindrance are also likely to allow dust, moisture, and other imperfections to enter the case with minimal hindrance. When a watch case is sealed to become water resistant, it also has the effect of keeping vibrational energy inside the case. The only way that the vibrations in the air inside the case can pass to the outside is by vibrating the thick case band and sapphire crystal, which saps a lot of energy and results in less volume.

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie (prototype)

Today’s market demands water-resistant minute repeaters that offer better reliability and require less expensive servicing than the unsealed repeaters of the past have done.

However, to make a water-resistant minute repeater sound as voluminous as a non-sealed model requires that the watch sound louder. What the team at APRP has learned in its years of research is that you don’t necessarily have to actually make something louder for it to sound louder.

Three patents

APRP’s mastermind Giulio Papi has a simple secret that guides him in his work: “Find and understand an existing need and then improve it.” He and his team have applied this to the Supersonnerie, which has resulted in three new patents.

Patent 1: the gongs.

The sound of a minute repeater originates at the gongs, and APRP’s first aim was to learn how to manufacture gongs that only make the desired frequencies. Even the best of chimes have a lot of undesired frequencies and harmonics that waste energy and degrade the quality of the sound.

Crystal-clear chimes are those with relatively pure frequencies. APRP’s patented gongs are manufactured so that they emit a better sound straight from the machine and require less tuning by the watchmaker.

Audemars Piguet Caliber 2937, the beautiful movement inside the Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie

Patent 2: the soundboard.

As APRP co-founder Papi explained, “Normally when you amplify sound you increase the volume of the unwanted noise as well as the desired frequencies. So we looked how to just amplify the good notes.”

Much of the energy from the repeater gongs is wasted in vibrating the movement components and the case, neither of which are likely to generate the sounds of pleasing chimes. To minimize the dampening effects from the movement and case, APRP developed a resonating soundboard for the gongs − just like those used in many musical instruments − that is sonically disconnected from the movement by a gasket. The gongs are fixed directly to the soundboard, and the movement is fixed to the case.

Case back of the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie: you can see the slots around the edge of the case back allowing the sound to easily escape in a focused direction (toward the ear)

The case back of the Supersonnerie protects the soundboard from physical damage from behind, but it also has another function in protecting the soundboard from the dampening effect of the skin. In a normal minute repeater, the air vibrating inside the case causes the case to vibrate. And where the case back rests against the wrist, those vibrations are dampened (and energy wasted).

With the case back off you can see the soundboard (under the finger) of the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie (the blue is protective tape)

On the Supersonnerie, the titanium alloy soundboard vibrates in the air unperturbed by being in contact with the skin. That conservation of energy means more energy is available for volume.

If you are a long way from me and I try shouting unsuccessfully to attract your attention, my next step might be to cup my hands around my mouth to focus the vibrating waves of energy coming out of my mouth. With cupped hands I am not physically shouting any louder, but by focusing the sound in your direction it will sound louder to you.

Attaching the case back of an Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie (the blue is protective tape)

The slots in the case back enable the sound to escape from the soundboard to the air unhindered; they also direct the sound so that the vibrations in the air flow along the arm to the ear.

As much, if not more, attention has gone into making the Supersonnerie sound louder (to our brains) as into actually being louder.

Chronograph pusher on the case band of the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie

Patent 3: the governor.

To activate a minute repeater, in general a slide or pusher winds a spring that unwinds as it powers the chiming mechanism. Left to itself, though, the spring would unwind too quickly, which would make the chimes sound too quickly and run into each other.

To slow down the chiming mechanism, a regulator is usually used, and this element falls into two main types. The first is the traditional anchor regulator that is like a little spinning fan; these are very reliable, but are relatively noisy. If you hear a whirr while listening to a minute repeater chime, that sound is the regulator at work. The second type is the inertia regulator, which has the advantage of being relatively quiet; however, it isn’t as reliable or long-lasting as the fan type.

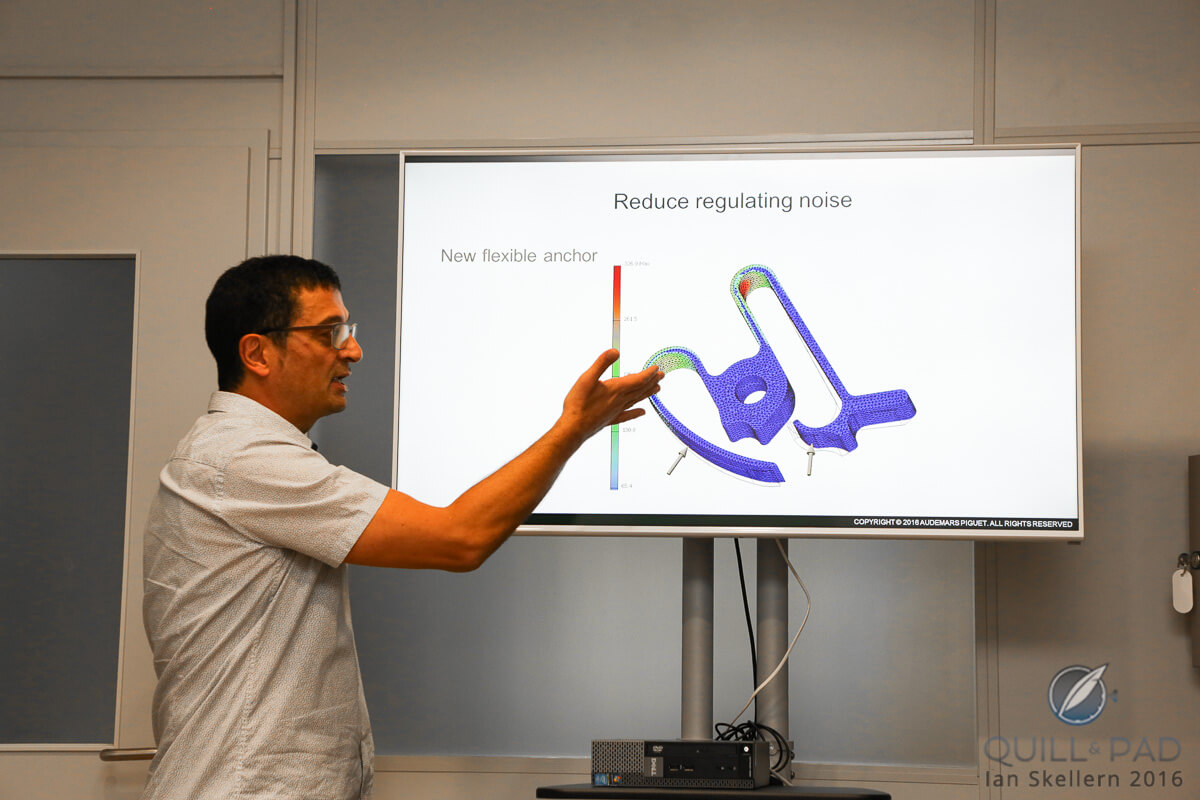

Guilo Papi explains the theory of the spring mechanism to minimize noise from the governor pinion in Caliber 2937 of the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie

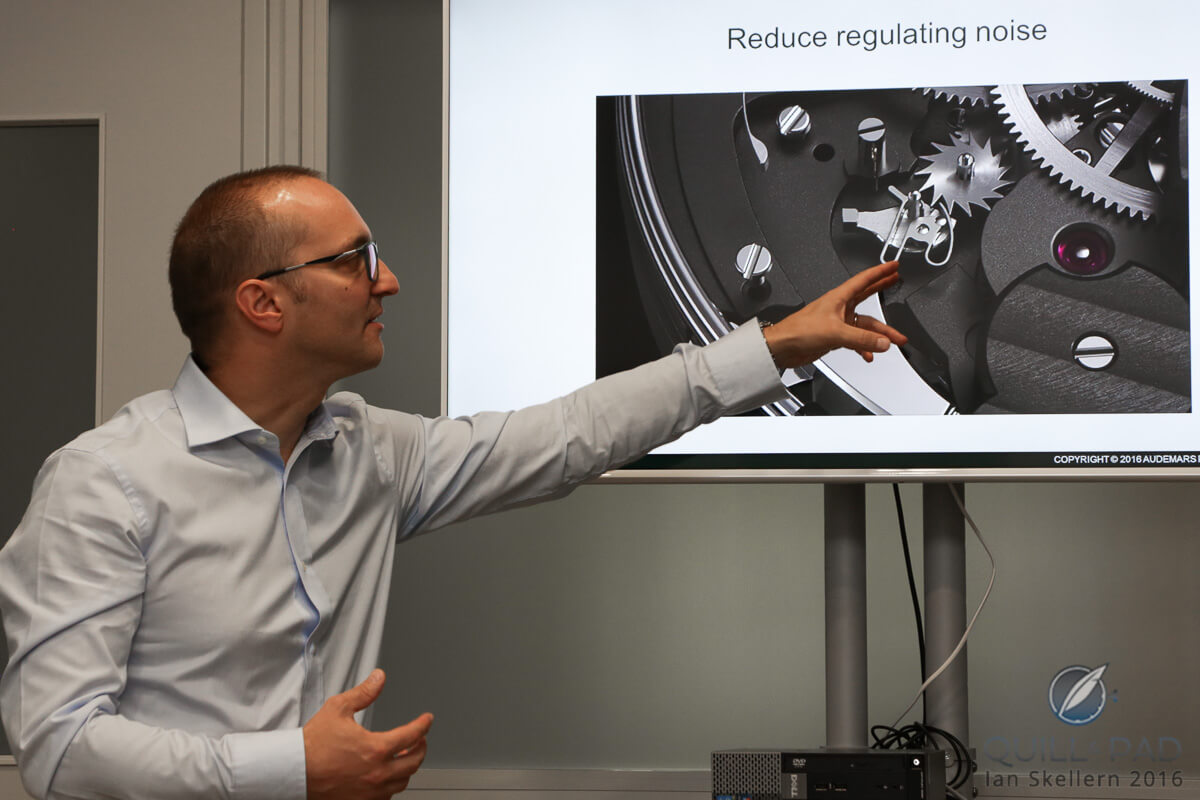

Audemars Piguet’s Claudio Cavaliere explains the reality of the actual spring adding tension to the governor to reduce noise in Caliber 2937, which powers the Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie

APRP’s research indicated that the majority of the noise from the anchor regulator came from the pinion vibrating in its axel bearing, so the technicians developed a little spring that eliminates that vibration. The result is a flexible anchor regulator that is reliable, long-lasting, and silent.

The sound of silence

When you listen to a normal minute repeater, there is always a gap between the gongs striking the hours and minutes up to three quarter chimes, which signalizes 45 minutes. If there are no quarters to be sounded (first 14 minutes after the hour) then there is a long silence taking the place of the time to sound quarters three times.

To eliminate this unwanted pregnant pause, Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi developed a new chiming mechanism to eliminate the unwanted long gaps of silence between chimes so everything sounds more harmonious.

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie on the wrist (the blue is protective tape)

Soundboards

It’s also worth noting just how much the use of a soundboard improves sound quality and quantity (volume) by itself, compared to just using a gong and hoping for the best. Normally, the sound waves (vibrations) are generated from the energy that the repeater hammer transmits to the gong when it strikes: that energy goes into making the gong, the movement, the case, and the air vibrate. As the waves reach our ear, we hear sound.

A significant amount of the initial energy (volume) at hearable frequencies is lost into wasted vibrations at frequencies that we cannot hear when the movement and case vibrate.

This exploded view shows the movement of the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie in the case at the top followed by the gongs, then the soundboard (shown as a copper disk here) and the case back at the bottom

The soundboard element of the Supersonnerie acts just like the soundboard found on violins, guitars, and pianos. Instead of a single (or double in the case of cathedral gongs) wire gong spraying its energy everywhere (movement, case, crystal, air), the energy from the gong is basically transmitted to a loudspeaker (the soundboard) that is pointing straight toward your ear.

You can see the slots around the edge of the case back that allow the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie’s sound to escape easily and in a focused direction toward the ear (the blue is protective tape)

Sound is subjective, more so when that sound is music because we each have different tastes and expectations for music. There’s a lot of bad music out there and are also a lot of bad repeaters. With the Supersonnerie, Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi didn’t set out to revolutionize the minute repeater; they simply wanted to make it (much) better. Minute repeaters play music, and there are myriad factors at play when we decide if we like the sound of a particular tune or not.

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Concept Supersonnerie (prototype)

As Papi explained, the Supersonnerie is, “Not a new minute repeater, we just improved many components.” And it really worked!

For more information, please visit www.audemarspiguet.com/en/watch-collection/royal-oak-concept.

Quick Facts

Case: 44 mm x 16.5 mm, titanium

Movement: manually winding manufacture Caliber 2937 with one-minute tourbillon

Functions: hours, minutes; chronograph with central sweep-seconds hand and 30-minute counter; minute repeater on two gongs

Water resistance: 20 meters / 66 feet

Price: $597,400

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] Further reading: Lange & Söhne Tourbograph Perpetual Pour Le Mérite: Building On Foundations A Synchronistic Tour De Force: Armin Strom’s Mirrored Force Resonance Hearing Is Believing: Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Supersonnerie And The Science Of Sound […]

-

[…] nerdtastic. It really stands alone as the best chiming watch this year and competes with the Audemars Piguet Supersonnerie for best chiming watch […]

-

[…] confirm this, my impression was that the Greubel Forsey Grande Sonnerie sounded comparable to the Audemars Piguet Supersonnerie in terms of both volume and tone . . . and it could easily be even […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Excellent article, Ian.

I love how they have improved on the existing concept of minute repeater. You cannot always get a great result like AP did if you go the revolution way. Kudos to those guys. They have just done it better.