Sometimes the most amazing discoveries are inspired by popular culture accidentally.

There have been numerous things brought to my attention thanks to their dramatized inclusion in a television show or blockbuster film including secret societies (like the Freemasons), ancient martial arts fighting techniques, underground street racing, and even the incredible women behind NASA and the space program in its early days.

Yet sometimes it takes repeated exposure before you realize the significance of a concept or perhaps an object. One example for me is the astronomical “machine” called the orrery. While a few of you may already be nodding in understanding, for the many who are likely to have no clue what an orrery is, it’s a mechanical representation of the orbits of planets and moons around our sun with varying levels of complexity.

Graham Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon

But let’s start at my “beginning” and let the details come from there.

My “whoa” moment happened when I visited the Long Now Foundation at the Fort Mason Center in San Francisco, California. While working in the bay area during the summer of 2010, I found out the Long Now Foundation was based in town, and I knew that they had made some cool clocks and mechanical computers as part of a 10,000-year clock project.

When I walked in, I was greeted by an eight-foot stainless steel mechanical orrery, an elaborate planetary display showing the relative positions of human-eye visible planets (Mercury through Saturn). It has six layers of mechanical-binary calculation engines and three layers of gear trains to drive the orrery display.

The stunning complexity and mechanical beauty of the mechanism blew me away, preparing me to be awed by the rest of what was on display. But that time with the orrery came to define the day, and united my passions of mechanics and astronomy. It was at that point that I started retracing my memory, discovering after the fact that popular culture had already brought it to my attention. I just wasn’t listening.

An orrey in the game “Rise of the Tomb Raider The Orrey Puzzle”

The orrery has played very important roles over the years like the final climactic sequence in Laura Croft Tomb Raider or as a harbinger of bad news in Pitch Black; one was visible in Dumbledore’s office in many of the Harry Potter films. Orreries are used in digital form in many space adventure movies such as Prometheus. An orrery even plays a pivotal role in the plot of Jim Henson’s Dark Crystal, predicting the end (or beginning) of the world.

While I had been aware of what they were for years, it never really hit me why they were so amazing or that I could have been nerding out for years on these mechanical marvels.

Orrery mechanics

After my visit to the Long Now Foundation and remembrance of the orrery’s lengthy role in film, the mechanism became a fixture of fascination for me and I learned as much as I could about it and its history. The history of the orrery runs alongside the history of clock- and watchmaking since the foundational concepts underpin moon phases, perpetual calendars, equation of time mechanisms, sunrise/sunset indications, sidereal time, star charts, and even the zodiac calendar.

The orrery is at once the most descriptive horological mechanism possible and the most fundamentally confusing to anyone not a practiced astronomer. If the appropriate scales can be added to an orrery, the positions of the planets, moons, and sun can tell you all the other possible astronomical values. But to add all of the appropriate scales in a readable way is practically impossible without making the orrery so large as to be inefficient bordering on useless.

That is why most orreries have a specific purpose (or purposes) in mind based on design and construction. The orrery, by definition, is “a mechanical model of the solar system, or of just the sun, earth, and moon, used to represent their relative positions and motions.” As the definition states, it is a model of the solar system but can sometimes be just the sun, earth, and moon to be considered an orrery.

This configuration also has another name, tellurium, which is usually used to show the cycles of the moon, eclipses (lunar and solar), and perhaps the seasons.

The tellurium configuration allows more detail to be shown for reference to those measurements, but when that isn’t the goal more planets can be added to show relative positions and orbits. A full orrery would include all the planets (yes, even Pluto) and each planet’s moons, as well as show the relative motion of each.

If someone only wanted to see the relationship between earth and moon that person would build a lunarium. Or if only the motion of Jupiter and its moons was desired, one would build a jovilabe.

Any other specific creation would fall under the general category of an orrery (unless the inventor created a new name for a new category). The mechanisms involved for each machine were different based on scale and chosen characteristics, but the basic setup is rather similar to most clock and watch gear trains because getting the relative movement of the celestial bodies is usually accomplished with simple gear ratios. The higher the number of total teeth or gears, the more accurate the calculation can be.

This is easily demonstrated with the classic moon phase function in a watch. The basic one uses a wheel with 59 teeth, leading to one day of inaccuracy every two and a half years (give or take). Increasing the teeth count to 135 makes the ratio much more accurate and allows for an error rate of a single day every 122 years.

Further accuracy is accomplished with multiple wheels to achieve a ratio closer to the actual equation; more teeth equates to more decimal places.

The same applies to every planet and moon in an orrery. Simple orreries can be created with basic ratios between two gears for approximate relative movement. But they need to be adjusted after a few rotations because the relative positions will soon drift.

Some orreries feature an entire gear train for each planet or moon, increasing the accuracy of the ratio and producing a much more precise celestial display. The Long Now orrery I mentioned previously used mechanical-binary calculation engines for extremely precise calculation (the goal was at least 10,000 years of accuracy, of course).

It’s not just history

This is why an orrery can become a nerdtastic horological machine, a must-have for any lover of mechanics. There has even been the option to easily build your own Orrey since 1918 by purchasing a kit with instructions from the much-loved Meccano construction sets. But like I stated before, the history goes back much further than that, coinciding with the scientific revolutions and horological invention.

The earliest mechanical models of the solar system were based on previous assumptions about the movements of the planets, usually with a geocentric solar system (isn’t that an oxymoron?) based on the Ptolemaic model or other theories. But as the scientific revolution progressed, the true movement of the heavens was becoming more understood thanks to scientists like Nicolaus Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, and Sir Isaac Newton, allowing the modern era of astronomy to gain momentum.

Clockmakers ended up being on the cutting edge of science and astronomy as they constructed the first modern orrery just after the turn of the eighteenth century. George Graham and Thomas Tompion made one of the first heliocentric solar system mechanisms and gave its design to John Rowley, a well-respected instrument maker.

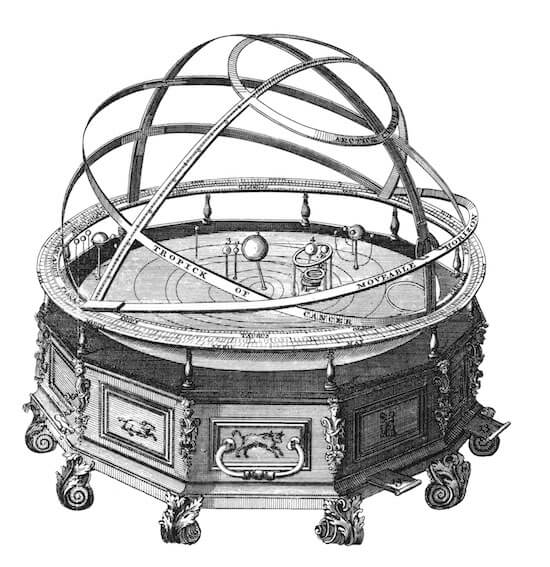

Drawing of an orrery by John Rowley from The Universal Magazine (image courtesy of www.blog.longnow.org)

Rowley was commissioned to make a copy for Charles Boyle, the fourth Earl of Orrery, a fateful commission if ever there was one. Because of this, the entire family of like devices was from then on known as “orrery” in honor of the earl.

This also led to Graham and Tompion being credited as the inventors of the orrery, as their machine was the one that led to the new name.

Fast forward to modern day and the watch company Graham that was founded to honor the memory of George Graham (see Historic Swiss Brand Angelus Is Back for more on Graham’s modern history), created a watch that honors his invention all those years ago. The Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon is a marvelous depiction of part of our solar system and a work of art at the same time as it is a feat of mechanical engineering.

Orrery on your wrist

The Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon is one of less than a handful of mechanical watches ever made that display the orbits of planets, and it’s the only one with a tourbillon rotating behind the sun. The movement, which was made exclusively for Graham by Christophe Claret, displays the orbits of the earth, moon, and Mars as they orbit around the sun, represented with a diamond cabochon in the center of an intricately engraved gold tourbillon bridge.

Graham Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon in pink gold with blue dial

The orbits are especially unique because instead of creating them concentrically (as is usual on small orreries), the orbit of Mars is eccentric and offset from that of the earth and the sun to more accurately display the difference in orbital paths.

The orbit of the earth is nearly circular so this is displayed concentrically around the center diamond; the earth has a very small moon that orbits it, a feature also not usually seen on orreries of this scale. The movement of the planets is mesmerizing during setting and gracefully slow during real-time operation. It is a great reminder of the longer time scales compared to what you focus on every day.

Of course the Orrery Tourbillon displays normal time – hours and minutes – with offset hands on the right side of the tourbillon bridge because it still needs to be utilized as an actual watch. But that really isn’t the point of a watch like this.

Since the orrery needs a calendar to accurately reflect planetary positions, the dial is labeled with the Gregorian calendar (365.25) days as well as a zodiac calendar around the inside of the planets for reference. In early astronomy, the science of astrology was so closely linked to it as to be indistinguishable, so historically this is an appropriate addition and nod to the origins of modern astronomy.

View through the display back of the Graham Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon

On the rear of the case the current year is displayed with a small indicator rotating around the circumference of the watch underneath a scale applied to the sapphire crystal case back. The scale displays 100 years, and the watch comes with two extra sapphire crystals to be swapped every hundred years providing accuracy for three centuries.

View through the display back of the Graham Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon

The years are also marked with indications of when the orbits need to be adjusted. The calculations for the mechanism favored the earth’s orbit, so that orbit is only off by one day every 1,156 years. The moon’s orbit, however, needs to be adjusted by one day every seven years, while Mars is adjusted every 25 years. These can be adjusted easily with correctors on the side of the case. All the orbits are set with a secondary crown at 2 o’clock.

The first version of the Graham Orrery Tourbillon had a different color dial and precious stones for the planets, but this new blue lacquer dial version features actual meteorite fragments from Mars and the moon for those representations and Kingman turquoise for the earth.

Graham Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon in pink gold with blue dial

The effect adds a little something special to something that is already very special. This new edition is an awesome update to the original, proving that Graham understands what horology fans really want.

The only downside to the Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon is that it’s a limited edition of only eight pieces, so very few people will ever be lucky enough to have one on their wrists. Still, seeing it in the metal and knowing that there are brands willing to produce such incredible pieces of horology is a comforting thought.

Graham Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon

The orrery is, to me, one of the most fascinating ways to discover and study the solar system without the danger of cosmic rays, and having one on your wrist means you can keep the solar system with you at all times. My personal history with orreries goes back to my youth, even before I knew I loved the mechanics behind them.

Graham Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon in pink gold with blue dial

It seems appropriate that I would be lucky enough to witness the creation of new and amazing examples of orreries for the next generation. They are part of our evolution as a species and a crucial machine to the development of science. Perhaps you will take a look not only at this amazing example, but at all orrery creations you can find to discover the universe laid bare.

For more information, please visit www.graham1695.com/index.php/watches/geo-graham/tourbillon.

Quick Facts Graham Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon

Case: 48 x 17.6 mm, pink gold

Movement: manual winding Caliber G1800 by Christophe Claret

Functions: hours, minutes; mechanical solar system displaying earth, moon, and Mars orbits with Gregorian and Zodiac calendars

Limitation: 8 pieces

Price: $330,000

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] While Graham is best known for its oversized Chronofighter chronographs, the British brand delights aficionados of astronomical complications at WatchTime New York with this exceptional mechanical masterpiece incorporating a miniature planetarium (see much more about orreries and this model in particular in The Graham Geo. Graham Orrery Tourbillon: Analyzing A Mechanical Wonder). […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Beautiful watches. Unfortunately, priced at significantly more than a quarter million dollars, it’s hard to get excited about them. Good article, however, it’s kind of like reading The Brothers Grimm, somewhat entertaining but deep down you know it’s a fairy tale.