Back in the late 1980s and early ’90s, mechanical watchmaking was beginning its incredible upswing to enter what is now widely known as the “mechanical renaissance.”

Big-name brands were once again becoming interested in advancing non-quartz watchmaking, and the small collector’s market willing to pay significant money for exceptional mechanical timepieces began to increase in size and scope.

The Swiss watch industry is by its very nature a cottage industry, so during this period a great many of the major complications were being developed by outside specialists with a particular penchant for thinking outside the box.

These suppliers included such firms as THA (Techniques Horlogères Appliquées, founded by three young French watchmakers François-Paul Journe, Vianney Halter, and De Bethune‘s Denis Flageollet), Christophe Claret, and Renaud & Papi – though, like the entire Swiss watch industry, the lines between the brands and the suppliers were often quite blurry and it may not have always been clear where one company or brand started and the other ended.

Renaud & Papi and RPC

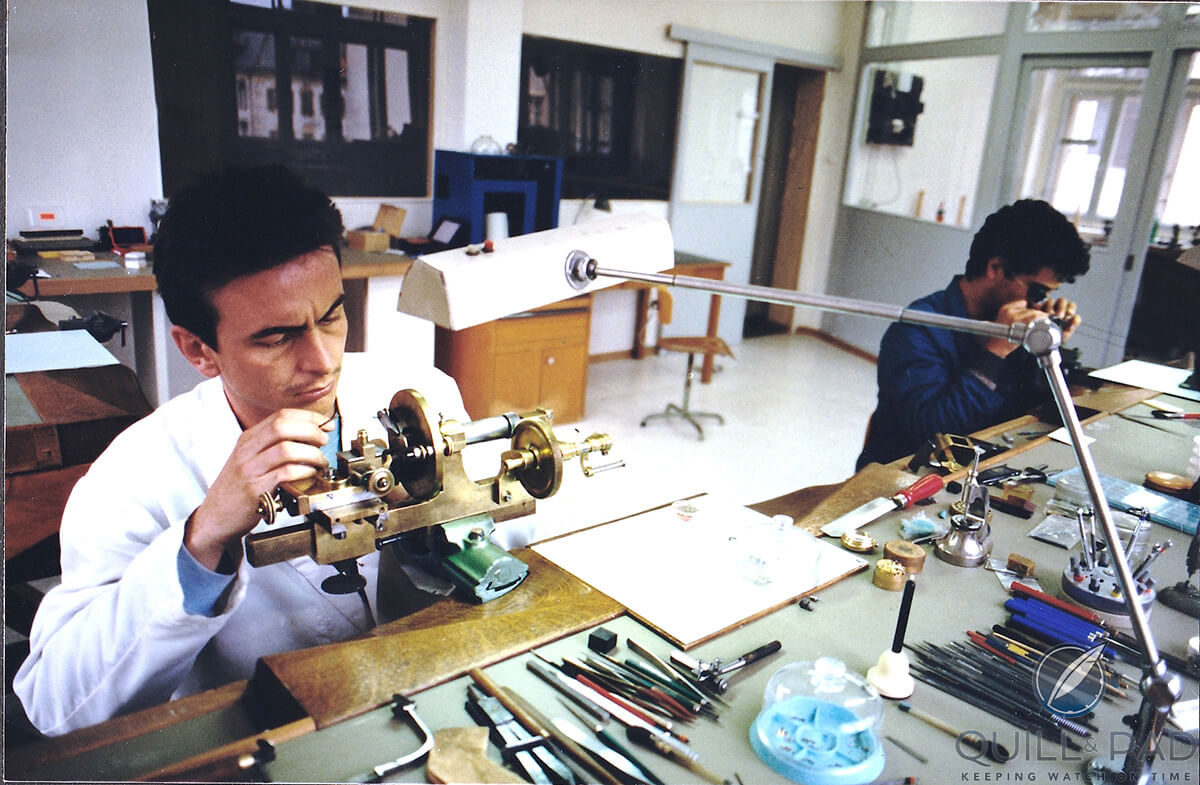

Dominique Renaud began working at Audemars Piguet in 1980. He received his watchmaker education in Besançon, though his family originally hailed from the Vallée de Joux.

“I was born and grew up in Besançon because my parents moved there after having met at Vacheron Constantin,” Renaud explains his heritage, which was founded in two important centers of watchmaking. “Growing up in an environment totally filled with watches and watchmaking motivated me to enter the local watchmaking school and dedicate myself to it.”

Both Renaud and Papi had previously been regular bench watchmakers at Audemars Piguet. They struck out on their own, founding Renaud & Papi SA in 1986 to explore avenues of high complication, which they had not yet been able to fully experience at Audemars Piguet although they had been working on watches as complicated as perpetual calendars.

“I stayed at Audemars Piguet for five years, learning what beautiful watchmaking really meant,” Renaud reminisces today.

At the 1987 Basel Fair, the late Rolf Schnyder, then owner and CEO of Ulysse Nardin, requested that Christophe Claret develop an exclusive minute repeater movement. While fulfilling this order, in 1989 Claret founded a company along with the two other ultra-talented watchmakers. This second company centered on the triumvirate of Renaud, Papi, and Claret was called RPC.

The partnership didn’t last nearly as long as the watches the trio created and ended in 1992, with Claret expressing a desire for independence. He bought up his partners’ shares and renamed the company Christophe Claret SA.

Papi and Renaud needed additional financing since they had no outside money invested in the company and needed to hire watchmakers to fulfill their own contracts. Audemars Piguet, one of their main clients, stepped in and purchased 52 percent of the company. In this way, the watchmakers’ previous employer, Audemars Piguet, made its first move toward securing its future in high complications.

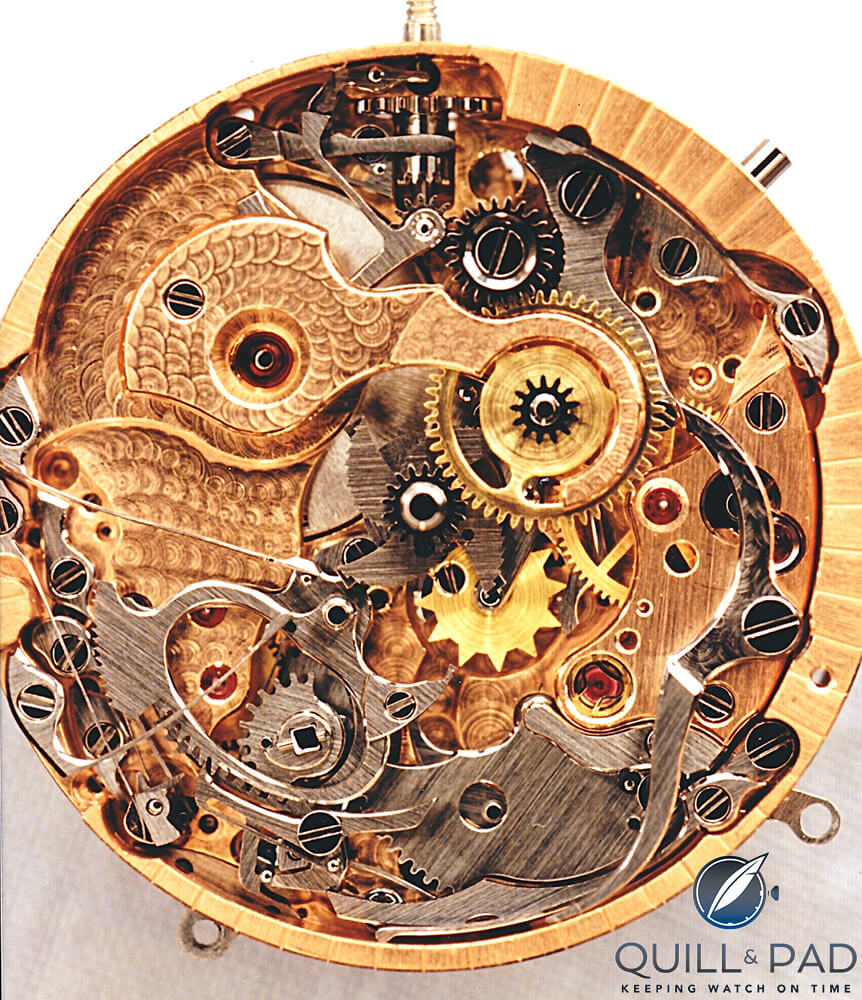

The bulk of the reputation of Renaud & Papi – as the company was now known – was based on the complication that it began life making: the minute repeater. And it should come as no surprise that this also remains Christophe Claret’s specialty.

APRP

Around the turn of the millennium, major changes occurred among Renaud & Papi’s leaders: Renaud sold all of his shares and departed, citing the need to take a break and refresh (it has been said he opened a bed and breakfast in an exotic locale).

“Then came the moment when I came to the conclusion I needed a break,” Renaud says today. “I wanted to step back in order to return with new ideas and start my own personal project.”

Robert Greubel, who had arrived in 1990 and was joint COO together with Fabrice Deschanel, also sold his 4 percent in 1999 and left. More history was made when he and another watchmaker also employed at Renaud & Papi as the chief prototypist – Englishman Stephen Forsey – first worked independently before founding CompliTime in 2001 and then Greubel Forsey in 2004.

The company officially renamed Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi (APRP) in 2003 after AP acquired a full 78 percent is based in Le Locle and now employs more than 150 employees under one roof.

Papi, who now manages the company together with Deschanel (who owns 2 percent), remarks that APRP can be likened to a “training ground,” and that it is designed so that others can also search out their own independence should that be the path they desire. Today, APRP describes its main services to brands as proposing ideas, specializing in quality finishing and decoration, and making reliable watches.

It is perhaps no coincidence that a number of the watch industry’s most creative horological minds have earned their wings at APRP before setting out on their own. These include Peter Speake-Marin, Andreas Strehler, Bart & Tim Grönefeld, and Stepan Sarpaneva to name just a few.

Skeletons, complications, and ringing chimes

Most watch fans are unaware that APRP has been behind a great deal of wonderful, complicated horology bought and sold under other names over the past 30 years or so.

Naturally, APRP was behind Audemars Piguet’s minute repeating oeuvres – and much, much more as time went on.

Richard Mille also makes no secret of how thankful he is to APRP for the great, reliable inventions that they have supplied over the 15 years since he founded his eponymous brand.

But few know that Renaud and Papi, along with Robert Greubel, were the masterminds behind the chiming complication module of IWC’s Grand Complication. “One day we went to IWC to meet Günter Blümlein and Kurt Klaus,” Renaud remembers. “Then a miracle happened: we connected well with Mr. Blümlein.”

APRP remains known in particular for its expertise in minute repeaters.

Renaud’s comeback

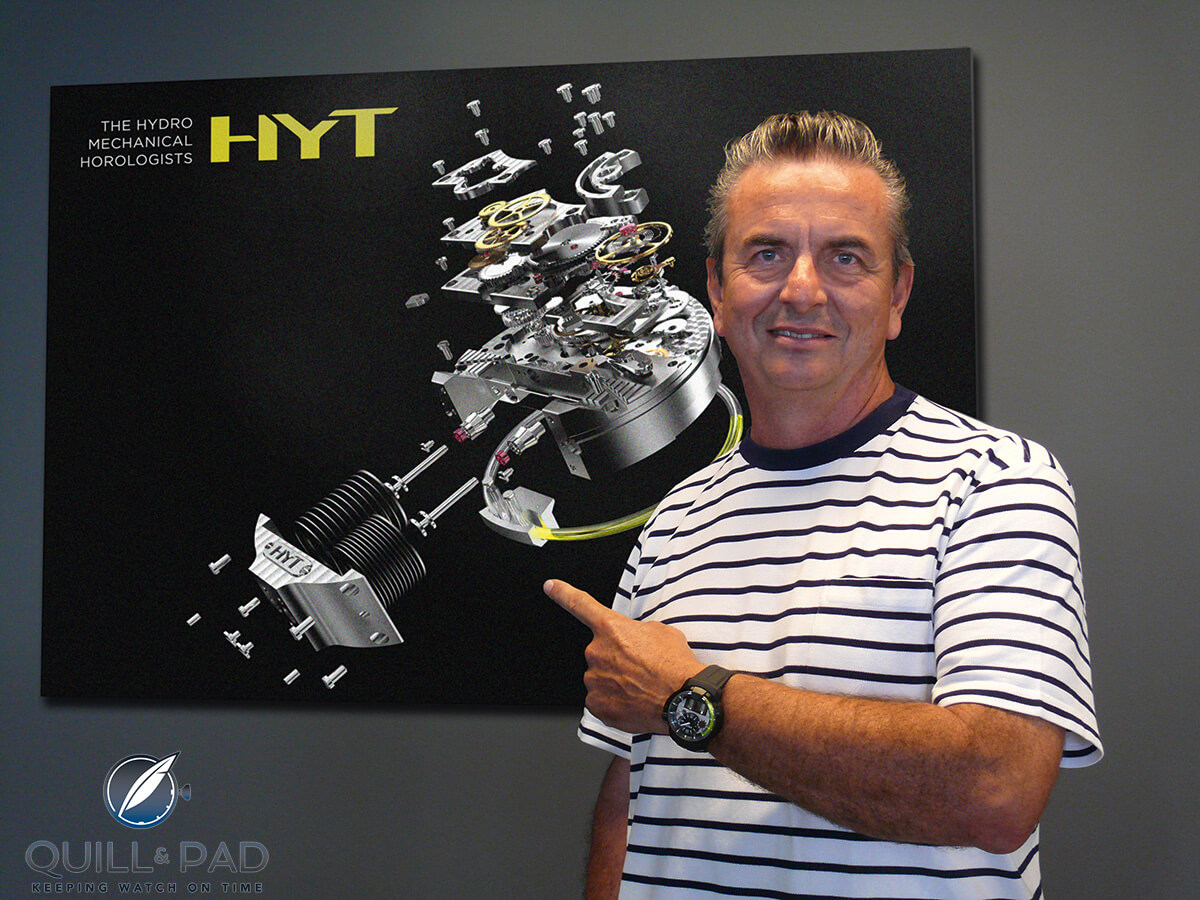

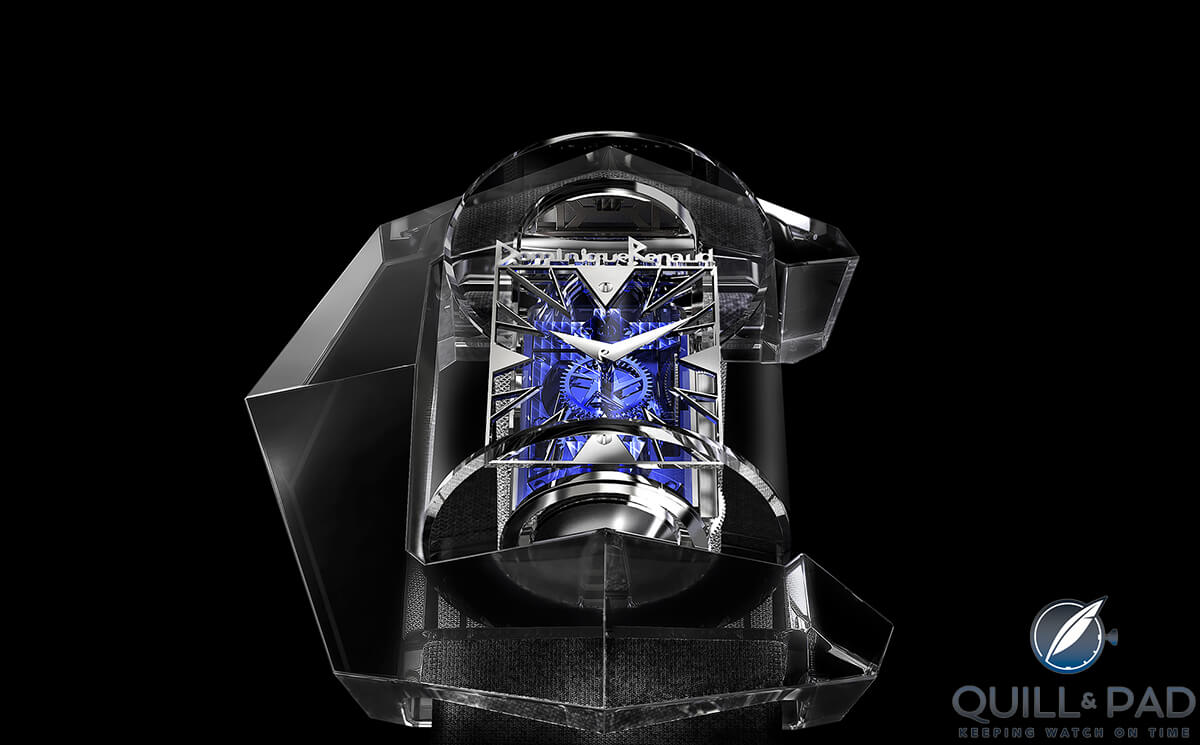

After fifteen years away from the world of watches, Renaud came back in 2013 and together with former Solar Impulse project director Luiggino Torrigiani founded Dominique Renaud SA. The idea being to create a Swiss watch innovation lab to develop original and highly complex movements.

“He spent years thinking and reflecting,” Torrigiani confirms. “He also built a conviction that it’s time to challenge the industry with a no-limits style of thinking.”

In 2014, HYT announced a collaboration with Renaud to help create interesting pieces of horology within the framework of its hydromechanical concept.

But what could be even more interesting are Renaud’s own projects yet to come. “I actually just invented something that I estimate will surprise many. This new escapement doesn’t have anything to do with what exists now. Some watchmakers might be shocked.”

For what came next, please see Dominique Renaud DR01 Twelve First: A Pioneer’s Return With The First Tangible Piece.

You might also enjoy:

MB&F’s Horological Machine 6 Alien Nation: Space Invaders Aren‘t Coming, They’re Already Here!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!