I have a personal relationship with Scotland. And with Edinburgh in particular. But I must (to my shame) admit that until recently I had not been inside the fabulous National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. And what had drawn me in was a temporary exhibition on Scottish pop music.

Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower in its original position in the National Museum of Scotland (photo courtesy M J Richardson/Wikimedia)

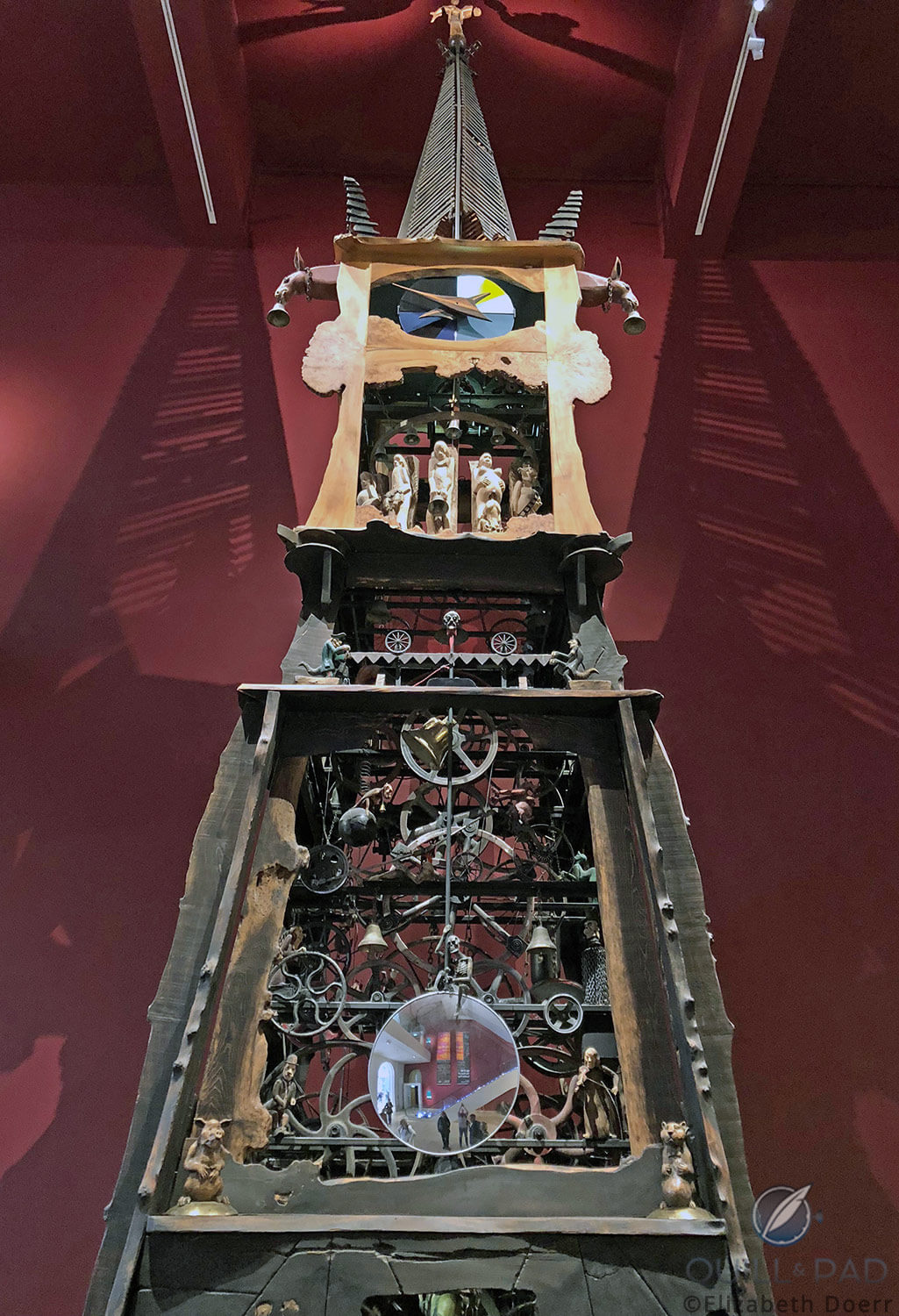

However, once at the museum and having seen the Millennium Clock Tower, which I had never even heard of before, all thoughts of going into the pop music exhibition were immediately forgotten in lieu of spending most of my time with this fantastical clock and deciphering its meaning.

“Millennium”: that’s clue number one

One meaning is found right in its name: “millennium.” This clock first chimed at noon on January 1, 2000, the first day of the new millennium. And, to be clear, it was not created to celebrate the new millennium, but rather to take a look back at the preceding 1,000 years.

Placed at the beginning in the main hall of what was then called the Royal Museum – the museum was re-named in 2006 thanks to a merger of two adjacent museums – the structure more than ten meters in height now resides at the entry to the Grand Gallery of the re-christened National Museum. Here, it choreographs the top of the hour using light, sound, and motion.

The clock was commissioned by Julian Spalding, then director of Glasgow Museums. “I had intended it for the great central court of the Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery in Glasgow,” the current art critic said.

“But it was impossible to raise the money. However, the National Museums of Scotland proved to be the clock’s fairy godmother, and it was finally created for the Great Hall of the Royal Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.”

In the end Mark Jones, director of the National Museums of Scotland, approved the project involving artists living in Scotland but immigrated from other countries and using Scottish materials for the National Museum in Edinburgh.

Initiators of Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower

The clock format was chosen by the inceptor of the project, Eduard Bersudsky, an underground Russian kinetic artist who moved to Scotland in 1993. Self-proclaimed sculptor-mechanic Bersudsky and theater director Tatyana Jakovskaya founded Sharmanka – a combination of “unique art and craft for thought and entertainment” involving sculptural kinetic art and theater craft – in Russia in 1988, but left due to that country’s growing economic depression and lack of local support for art.

Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower in the National Museum of Scotland

Spalding invited Sharmanka to exhibit at McLellan Galleries in 1993 and purchased three of the duo’s kinetic sculptures for the Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art. By 1996, Sharmanka had received a significant grant from the Glasgow City Council to build a performance hall and improve its gallery. It has since become one of Glasgow’s “sights.”

The Millennium Clock Tower is Sharmanka’s largest project to date. The clock format certainly satisfied Bersudsky’s kinetic artistic vision even as it symbolizes the march of time.

Bersudsky and Stead: artists for Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower

Bersudsky was in charge of the clock’s mechanics at large, the kinetics, and the carved figures within the clock structure. Born in 1939 in Leningrad, he is an autodidactic visionary artist who started sculpting and carving in his late twenties. He made his first animated sculpture in 1968, a genre of statues with motion he calls “kinemats.” Bersudsky’s work can be found in museums in St. Petersburg, Jerusalem, Warsaw, and Granada as well as in private collections. He also creates touring sets, commissions, and collaborative art.

Bersudsky knew he could not create this gigantic project on his own, so he enlisted the aid of other artists.

One of these was sculptor and furniture maker Tim Stead (1952-2000), who had taken the Sharmanka workshop into his country house in Blainslie in the Scottish Borders from 1993 through 1995.

A side view of Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower with burnt-out wood paneling and stained glass “eyes” around the crypt portion

Stead, awarded an MBE in 1999 for contributions in UK woodland restoration and community participation, created the clock’s base, the wooden buttresses, the timber cladding, and the spire. The Millennium Clock Tower was his last project; he passed away in April 2000.

Stead created the framework of the tower using pine for the base and elm for most of the rest, much of which he burned with a blowtorch to burn out the soft summer growth and highlight the winter growth.

“The Tower is mainly dark burnt timber, which represents the depressing history that we have of continual wars, destruction, and exploitation of people and natural resources,” Stead, whose greatest source of inspiration was the buildings on the island of Orkney, has written. “Nature will always survive, and there are always green shoots of optimism that emerge after a fire.”

Stead’s wife, linguist and graphic artist Maggy Lenert, also participated in the project.

Sandström and Tübbecke: artists for Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower

Glass artist Annica Sandström, born in Sweden but living in Scotland since 1978, made the clock’s dial, side panels, and crypt “eyes.” Sandström and American glass artist David Kaplan are the founders of Lindean Mill Glass in Selkirk, also located in the Scottish Borders.

A side view of Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower featuring Annica Sandström’s stained glass panels

The final link in this millennium-themed chain is Jürgen Tübbecke, a watchmaker originally from Germany but at home in the Scottish Borders since 1979 by way of Switzerland (where he received his training) and South Africa. Tübbecke’s first commission in Scotland as an independent clockmaker specialized in restoration and repair in Galashiels was to make a clock for Glasgow’s Café Gandolfi in 1980.

Tübbecke restored a large pendulum clock from the 1880s for use in the Millennium Clock Tower that had been found in a farmer’s shed in the Scottish Borders. Outfitted with a deadbeat escapement, it strikes the hour. Its enormous pendulum weighing 26 kilograms is 2.2 meters in length.

Artistic symbolism over timekeeping

On the day I discovered the clock, I was fortunate to catch the noon chiming session, which I immediately noticed was about playing the organ music (the third movement of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Concerto in A Minor BWV 593, allegro), moving some of the figures, and setting off the light show. The clock did not chime, nor were the hands in their stained-glass dial set to the right time.

My assumption is that the mechanical movement no longer works and that the rest of the features are driven by electric motors.

A side view of Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower reveals that it is rife with detailed symbolism of humanity’s not-so-distant past

But in the larger scheme of things, I’m not sure that part is all that important. On the Sharmanka website, Bersudsky explains that this creation contains “fragments of the story of the [past] millennium, with its disasters, tragedies, but also its human, scientific and artistic achievements. A creation that talks of love, hate, work, play, humor, despair, life, and death.”

The Millennium Clock Tower does not even attempt to show or explain everything from the past millennium along its ten meters’ worth of art. As a monument to human history, it poses questions and leaves question marks thanks to the many figures left to the interpretation of the beholder.

“Essentially it is human beings with their own characters which are caught up in the wheels of time, of progress, of war, of political games, of belief, and disappointment,” Bersudsky wrote.

Four (not three) sections of Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower

This work of art has some religious symbolism, but it is not overwhelmed by it, which is evident in the fact that it is separated into four sections, rather than the usual three of religious-themed artwork symbolizing the holy trinity.

The Egyptian monkey and the ancient spirit in the crypt portion of Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower (photo courtesy Dun Deagh/Wikimedia)

The crypt

The lowermost quarter is called the crypt, and it is not only the base of the clock tower, it also symbolizes the base of society. Among the vintage cogwheels, there are two distinct figures here: an oaken figure of an ancient spirit in chains and a busy Egyptian monkey (a symbol of the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth).

The nave

Above the crypt is the nave, which is dominated by more cogs and wheels as well as the mirror-polished pendulum bob.

A skeleton figure representing death sits on the pendulum bob, swinging to and fro along with the motions of the timekeeper, which – as far as I saw – is only in motion for the length of the Bach concerto played at the top of the hour. The pendulum is not part of the functioning movement but is simply part of the show. It does not swing regularly, but rather erratically.

The top end of the pendulum is presided over by a dark head with red eyes meant to symbolize Lenin, founder of the Russian Communist Party. Lenin is joined on either side by Hitler and Stalin, each outfitted with a reptilian tail. It is this unholy trinity who decides the pendulum’s tempo, not physics.

If you look closely you should recognize a Charlie Chaplin figure in the nave portion of Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower

The nave is populated with a variety of other moving figures, too, all carved by Bersudsky: a jester, Charlie Chaplin, and Einstein playing the violin frolic among a variety of symbolic creatures.

The belfry

The light show hits the “requiem” and the clock dial of the belfry in an especially exciting way thanks to the colorful glass panes that surround it.

The light from the glass panels play on the requiem figures in the belfry portion of Edinburgh’s Millennium Clock Tower (photo courtesy Dun Deagh/Wikimedia)

The requiem comprises a circle of 12 carved figures, which do not individually move but rather stand on a slowly rotating platform that comes full circle every hour. Seen up close, they are somewhat shocking, while from a distance they look perhaps like the dead in shadow form.

These figures represent hardships and tragedies that afflict or have afflicted humankind in the twentieth century. Their individual names are: Hunger, Madness, Grief, Forced Labor, The Martyr, The Old Clown, Pandora’s Box, The Holocaust, The Intellectual, The War Invalid, War Camps, and The Hermit.

The belfry of the Edinburgh Millennium Clock Tower is dominated by the requiem and the glass panes

Glass is the most contemporary element of the whole clock tower, and the belfry is its home. Sandström used the so-called Overfang technique to create these panes, which includes casing the glass in several layers of color, sandblasting it, and then blowing it into the form of a cylinder. Then it is cut, fused in the kiln, and repeated several times.

Are there bats in the belfry? I didn’t see any.

The spire

The spire is a light wooden construction looking something like you might see after a building has been destroyed by a fire, but with a completely visible and intact bell. Its shape also resembles spires seen on Edinburgh’s own unique skyline in the old town.

The spire portion of the Edinburgh Millennium Clock Tower is topped by a carved wooden pietà figure

Considering its symbolism, I see the spire as penetrating the sky to reach the heavens. The tower itself might be the symbolic tree of life, resting on heaven, earth, and the underworld, branches reaching toward heaven and roots descending into the dark abyss with the belfry and the nave symbolizing the hopes, dreams, and imagination of humankind.

While these levels remind us that we are human, fallible, and imperfect, the top of the spire – the carved wooden pietà figure of a woman holding a dead man symbolizing mourning and compassion – is a reminder that we can always do better in the futures we have the power to create.

For more information please visit www.nms.ac.uk/explore-our-collections/stories/art-and-design/millennium-clock-tower.

You might also enjoy:

De Fossard Solar Time Clock: Appreciating An Extreme Achievement Without A Loupe

Artist/Engineer/Clockmaker Florian Schlumpf’s Deconstructed Time

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

However, once at the museum and having seen the Millennium Clock Tower, which I had never even heard of before, all thoughts of going into the pop music exhibition were immediately forgotten in lieu of spending most of my time with this fantastical clock and deciphering its meaning.

“Millennium”: that’s clue number one

One meaning is found right in its name: “millennium.” This clock first chimed at noon on January 1, 2000, the first day of the new millennium. And, to be clear, it was not created to celebrate the new millennium, but rather to take a look back at the preceding 1,000 years.

Placed at the beginning in the main hall of what was then called the Royal Museum – the museum was re-named in 2006 thanks to a merger of two adjacent museums – the structure more than ten meters in height now resides at the entry to the Grand Gallery of the re-christened National Museum. Here, it choreographs the top of the hour using light, sound, and motion.

The clock was commissioned by Julian Spalding, then director of Glasgow Museums. “I had intended it for the great central court of the Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery in Glasgow,” the current art critic said.

“But it was impossible to raise the money. However, the National Museums of Scotland proved to be the clock’s fairy godmother, and it was finally created for the Great Hall of the Royal Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.”

In the end Mark Jones, director of the National Museums of Scotland, approved the project involving artists living in Scotland but immigrated from other countries and using Scottish materials for the National Museum in Edinburgh.