Mind ache: the best – and worst – feeling of learning. And the reason you may have said about a difficult subject in school (perhaps a foreign language or math) that it was “so hard it hurt.

When you push the human mind to the limits of its understanding, it is forced to engage more neurons in an attempt to unravel the inputs it is receiving.

There are two general modes of thinking that a brain uses: sequential and parallel. Parallel thought, often called intuitive or automatic thought, is usually performed by recalling stored information and offering it up without verification. Examples of intuitive thought include tying your shoes or singing your all-time favorite song; activities requiring little mental effort once mastered/memorized. Brains automatically send instructions on what it already knows with little conscious thought.

But when you are receiving new information or information that is unclear or unfamiliar, the brain switches to a different mode of thinking called sequential thought. This results in a slow and careful examination of the information and a deliberate evaluation of its meaning, usually one piece at a time.

Sequential thought is harder than parallel thinking so requires more mental energy, which actually burns calories. Now if the only downside to sequential thinking was that it was slower, people still might be able to learn with relative ease.

But the bigger problem is that sequential thinking uses a person’s working memory, which is a function of short-term memory limited to holding just four or five novel ideas at once. This drastically limits our ability to take in large amounts of new information.

To expand working memory, the brain can group things together into larger ideas (called chunking), which allows a person to hold four or five chunks of information. The bigger and more complex the chunks, the more complex a concept a person can sequentially consider.

So, for example, instead of trying to consider every individual component that makes up a car (thousands), one can simply use the idea of a “car,” making it a singular chunk, allowing more chunks to be considered in the working memory.

But what does this have to do with mind ache and how in tarnation is this going to relate to watchmaking?

Well, learning new topics, especially difficult ones, stresses your working memory and uses large amounts of energy in an attempt to categorize and comprehend the topic at hand. This is made easier if you are familiar with the core concepts but is made more difficult as it varies from your base knowledge.

I love learning about mechanical systems and since I understand the core ideas pretty well, new mechanisms are usually rather easy to understand in a timely manner.

But every once in a while I get a case of mind ache as I am pushed to the edge of what my working memory can hold; the more I concentrate, the more information I am trying to force my brain to hold at once. This makes my head literally ache from the pressure to understand something new.

The latest culprit behind a case of mind ache is the Krayon Everywhere watch, an easy-to-read yet deceivingly complex timepiece that can show you sunrise and sunset times for any location on earth (with some limitations).

Krayon Everywhere on the wrist

Krayon Everywhere: mechanical love

I knew from the moment I heard about the Krayon Everywhere that I was in love with it mechanically. I didn’t even need to see the movement to know that I would be lyrically waxing (or my best approximation of waxing lyrically) the ingenious solutions that its creator, Rémi Maillat, had undoubtedly come up with.

Remi Maillat, Krayon Everywhere founder and inventor

I knew from research (which was now easily recallable from my long-term memory) that creating a mechanism displaying sunrise and sunset times was difficult by itself and required a specific geographical location for the mechanical calculations and gearing.

I understood that creating an indication capable of displaying sunrise and sunset times for the entire world would be a difficult task to achieve mechanically. However, it was only when I started actively using sequential thought that I began to understand the scale of the “chunks” of information required to understand what would be needed mechanically.

It is a tall order, to be sure, and understandable that Maillat worked on the project for four years, including two years of mathematical calculations to show that the concept was even theoretically possible, then another two years for development and production of the first pieces.

How to use the Krayon Everywhere

But I am getting ahead of myself, so let’s start at the beginning. What does the Krayon Everywhere do?

Thanks to a simple display using two overlapping disks, it is able, after being appropriately set, to display the time of sunrise and sunset at your location. This is where the mechanical trouble lies because as latitude (moving north or south) and longitude (moving east or west) changes, the relative times of sunrise and sunset can vary quite dramatically throughout the year. We’ll come back to that.

On the Krayon Everywhere, the sunset and sunrise times are read via two overlapping disks visible in a ring around the edge of the dial. Each disk contains a lighter section showing the current amount of daylight and a dark section representing the night. The boundary between light and dark is the actual time of sunrise and sunset, with the two disks overlapping in the middle of day and night so that the length of each can be adjusted. There is even a handy overlay with a scale to read how many hours of sunlight there are.

The disks rotate separately from each other and when adjusted either reduce the length of the night, uncovering more of the lighter section and overlapping the dark section, or increase it, resulting in more of the dark section being visible (and the lighter section overlapping more).

The specific time of sunrise and sunset is read using a 24-hour track around the outside of the disks and a regular minute track on the inside.

The hour hand is incorporated into the ring, floating above the day/night disks and pointing to the current hour, providing a clear connection to the sunset and sunrise times in hours. In this way, the hour hand is a visual representation of where the sun is located at any point in the day.

The minutes, imprinted with hash marks and numerals at five-minute intervals, are displayed via a regular sweep minute hand.

The sunrise and sunset times are read by noting when the hour hand is directly above the boundary between day and night, reading which hour it is, and then adding the current minutes being displayed.

There is obviously a little wiggle room for interpretation, but the hour hand has a very small notch out of the bottom allowing you to see when it lies directly over the boundary, with a black line differentiating the two sections.

How to set the Krayon Everywhere

To program the watch so it knows where you are on the planet and will display the sunset/sunrise times accurately, you must set the longitude, latitude, UTC offset, the date, and, of course, your local time. Each one is set via the crown after being selected by the push button at 8:30.

There is a crown position for time setting and another for date (and all other options) so it is very intuitive.

By changing the month and date on the lower subdial, the two overlapping disks slowly adjust relative to each other as the sunrise/sunset times shift throughout the year, moving earlier or later as the solstices approach.

Next, adjusting the longitude displayed in the upper subdial rotates both the disks together around the dial as a function of the UTC offset (UTC, or Coordinated Universal Time, is commonly called GMT, though GMT is really the name of a time zone and UTC is the time standard).

The function is basically adjusting any hour shifts that come from a longitude/UTC relationship. This means that if you set the watch to +0 UTC (which puts you in Great Britain), but at 180° longitude (the international date line in the Pacific Ocean) it actually flips the day and night even though this is a physically impossible location as you can’t be in England and the Pacific Ocean at the same time.

But the function is mainly included to adjust the longitude relation to the UTC offset, since UTC sections do not rigidly follow lines of longitude and are, instead, kinda wonky.

The UTC offset is mainly there to make sure the watch knows exactly which time zone you are in should that create a special circumstance – like, for example, Dawson, YT, Canada and Las Vegas, Nevada, US, which are more than 24 degrees apart based on longitude (time zones are approximately 15 degrees wide) yet still in the same time zone.

This dial also has a handy notation for Daylight Savings Time, helping you adjust UTC position should your location observe DST.

Finally, we get to the most variable adjustment: latitude. Adjusting the latitude makes the disks expand or contract relative to each other, with the change moving faster as the longitude approaches the 60-degree maximum setting.

Farther from the equator, sunrise and sunset times vary more dramatically, creating a display that changes much more over the year. When the setting is near zero, or near the equator, the disks will change very little over the year.

The nerdy information: AKA, why I had mind ache

Setting and using the Krayon Everywhere is remarkably simple. Aside from requiring you to Google a couple key numbers for latitude and longitude, it isn’t any more difficult than setting a basic calendar watch.

But that isn’t what makes this watch so terribly complex and the instigator of my mind ache. It all comes down to how it actually displays information that, in itself, is decently complicated to capture in a mechanical system.

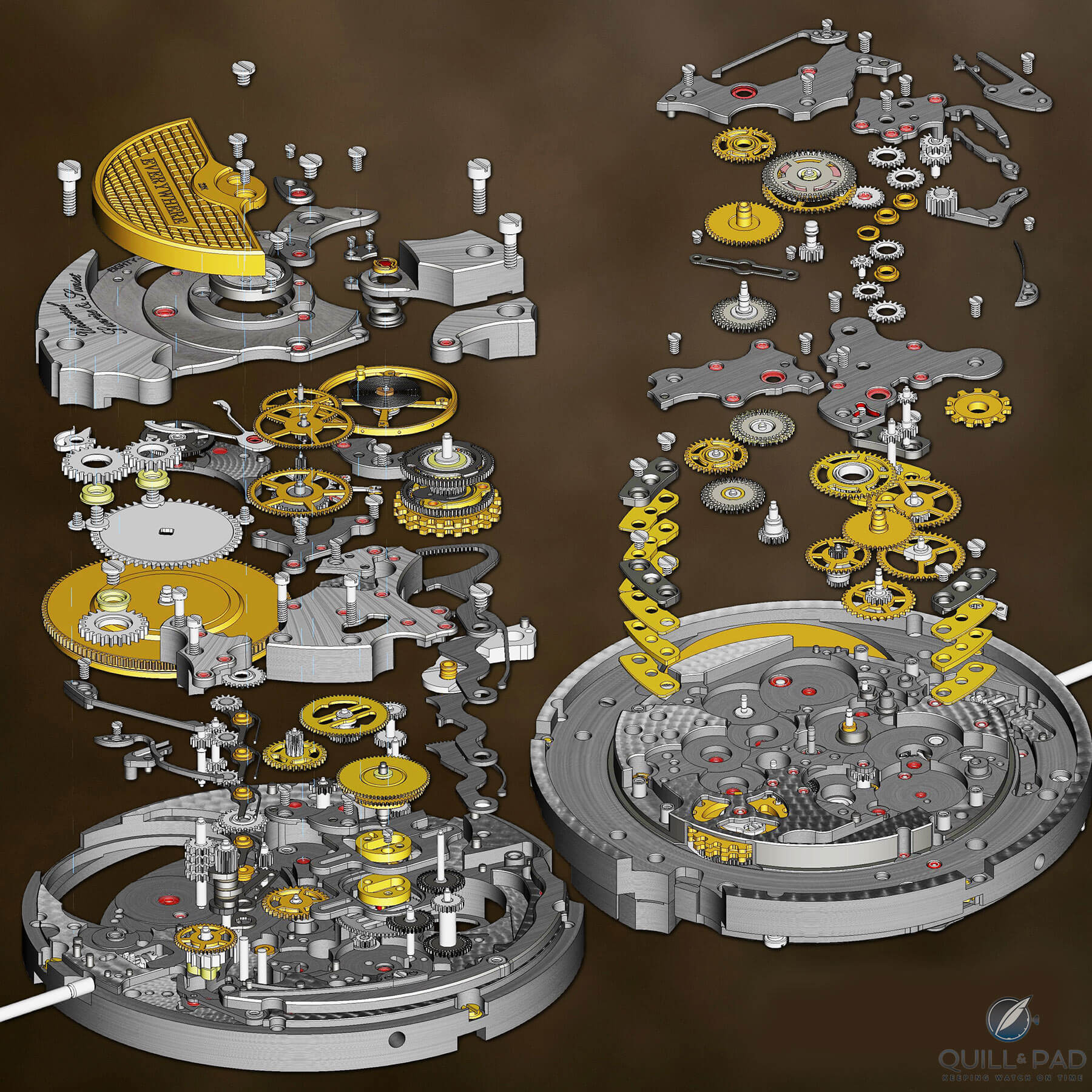

The movement for the Everywhere uses 595 components, 145 of which are gears making up 84 gear assemblies, including four (you read that right: four) differentials to calculate the sunrise and sunset times.

Interestingly, you won’t find any star wheels or components normally found in date mechanisms, since they are often prone to damage from improper setting. Everything in the Everywhere uses gears and differentials to ensure smooth forward and backward setting, effectively preventing accidental damage.

Clearly visible above the case band pusher at 5 o’clock are the stacked wheels on just one of four differentials in the Krayon Everywhere movement

Perhaps even more interesting is an equation of time mechanism concealed inside doing the heavy-lifting calculation (with no indication on the dial), but it does not appear to use the standard equation of time cam profile as utilized by practically every other equation of time mechanism. Instead, the Everywhere uses two stacked cam profiles — offset from each other and from the solstices (more on that later) — each cam individually driving the sunrise and sunset displays.

The complexity was surprisingly unfamiliar because the solutions were not what I was expecting based on my previous knowledge. So after receiving a bunch of movement schematics and videos of different mechanism operations from Maillat, it took only a short while before I started to have a mind ache.

It was, at first, like staring into the organized chaos that was the mechanical calculator. No wonder my brain hurt: it was trying to take in way more than four or five novel ideas at once.

Krayon Everywhere

Krayon Everywhere: making matters worse

I already had enough to consider with all of that, so when I went to learn about the technical challenges faced with the calculations for the sunrise/sunset display, it only compounded my mental struggles to collate all the information.

NOTE: All of the following information is not needed to understand how to use or appreciate the Krayon Everywhere. It simply illustrates the further complexity that makes the Everywhere so awesome. If you want to skip the boring sciency stuff, head down to the final section “Design thoughts.” Otherwise, read at your own discretion.

It all comes down to the equation of time compared to mean solar time and is further related to latitude and longitude. Yeah, it’s a bit confusing.

Sunsets and sunrises vary throughout the year, slowly drifting apart as the summer solstice approaches and toward each on a the winter solstice approaches. Sunsets and sunrises also drift relative to each other. As well as swapping places for each solstice.

At the summer solstice, the latest sunset occurs after the solstice, while the earliest sunrise occurs before. Six months later at the winter solstice, the earliest sunset has drifted to before the solstice, while the latest sunrise is after.

To add complexity to this, the amount of offset from the solstice varies based on latitude. At my location in Atlanta (33.7490° N latitude), they are offset from the solstice by about eight days at the summer solstice and about 17 days at the winter solstice.

On the equator, such as in Pontianak, Indonesia, the variance is much greater. At the summer solstice, the sunrise and sunsets are offset by about 35-37 days and at the winter solstice it jumps to a whopping 50-52 days.

Now if you traveled north and stopped in Helsinki – the northernmost location for which you can use the Krayon Everywhere (it maxes out at 60° latitude) – it shrinks to a measly one to two days at the summer solstice and five to six days at the winter solstice.

That is a huge variable to account for, but it doesn’t end there. The time difference between the earliest and latest sunsets and sunrises varies inversely by latitude. At Pontianak on the equator, the variation in sunrise is only 18 minutes a year – and only 23 minutes for sunset. So they pretty much stay at about the same time all year, and the days are fairly similar in amount of daylight.

But up in Helsinki the sunrise varies by a much larger 5 hours, 32 minutes, and the sunset pushes it even further with a total difference between the solstices of 7 hours, 39 minutes. This creates days with almost 19 hours of daylight in the summer versus a paltry 5 hours, 49 minutes of daylight on the winter solstice.

That enormous variation in parameters is why the Everywhere watch isn’t actually the “everywhere” watch it claims to be, because when you go just 5.5 degrees past 60° N, there are a few days with no sunset at the summer solstice and no sunrise at the winter solstice. However they cannot (not yet at least) make the sunrise/sunset disks disappear from the dial, so a limit had to be chosen that made sense mechanically.

Astronomy nerd side note: Alert, Nunavut, Canada is the northernmost permanently inhabited settlement on earth at 82.5018° N, just 508 miles south of the North Pole. During the long, bright summers, Alert sees 152 days straight with no sunset. And after a short five and a half weeks of sunrise and sunset, it plunges into darkness for 134 days until the next sunrise, which occurs around February 26.

Krayon Everywhere

And one final annoying addition to consider: a location’s longitudinal position won’t necessarily match it’s UTC time offset due to arbitrary boundary lines made to include whole countries, islands, and keep things from becoming messy for mean civil time. All of these factors combined (plus a non-universal use of daylight savings time) makes the gear calculations inside the Krayon Everywhere a royal pain in the neck.

It’s worth repeating: Maillat took two years just doing the theoretical calculations, then another two years to make the whole thing.

Krayon Everywhere: the magic of mechanics

So what is all that complexity comprised of? The short answer is: quite a lot. But I’ll elaborate.

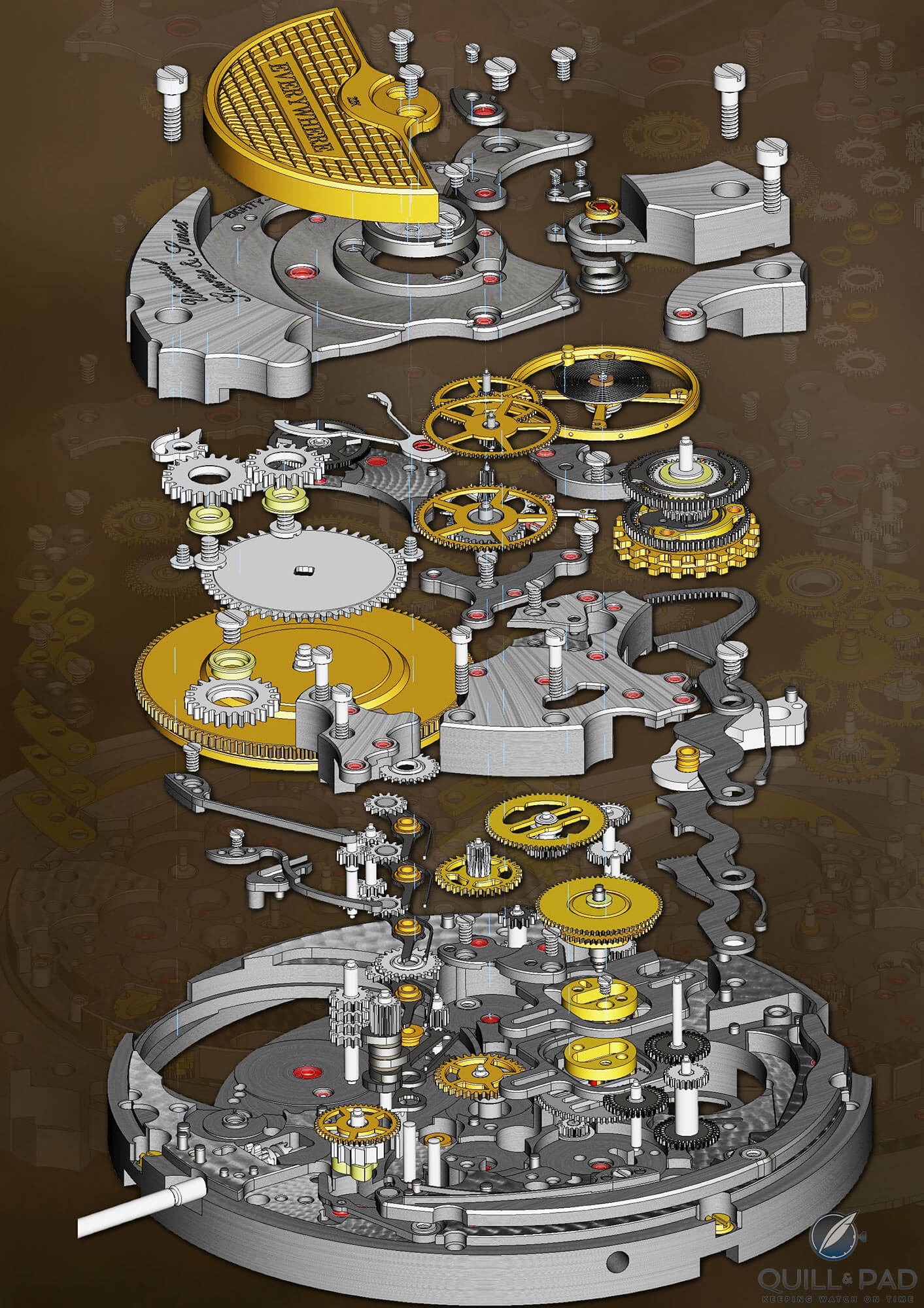

Exploded movement of the Krayon Everywhere

The Krayon Everywhere watch is based on multiple interacting gear trains averaged by four differentials in a continually changing set of disks displaying sunrise and sunset at a given location. As previously stated, there are two stacked cam wheels driving two rectangular-shaped racks, which, in turn, drive the majority of other calculations.

The two cam wheels are mounted on a gear with a channel in it allowing the cams to be adjusted, becoming more or less eccentric as a function of latitude. The higher the latitude, the more off-center the cam wheels become. If your latitude is zero, then the cam wheels are as centered as possible and the only variation is largely the difference between the two cam shapes.

The cam profiles are offset from each other to map the back-and-forth drift between the solstices as well as the overall equation of sunrise/sunset time. The position of the gear holding the cams is a function of the date and month, so combining the two creates a complete calendar of the sunrise and sunset variation.

Exploded movement of the Krayon Everywhere

But that’s not all: there’s still longitude and UTC offset to consider, which through a differential and meet up with the gear train driving the sunrise/sunset display disks.

Both the sunrise and sunset disks have individual differentials between them and the rest of the gear trains for the final calculations. The disks overlap each other and both carry a portion of the night-and-day display, with enough hidden to allow the display of the extreme differences at high latitudes at the solstices.

When you have four differentials and different gear trains meeting, you must also be able to adjust each one to set an accurate location, date, and time reference. This is made possible by the longest stack of cams I have ever seen in a watch. The selector mechanism is based on a shaft comprising five separate cam lobes making the adjustment mechanism as clever as everything else in the watch.

This tiny mechanical masterpiece begins with a stack made of a tri-lobe cam, a 12-tooth ratchet wheel, and a gear wheel. The push button on the side of the case activates the tri-lobe cam and rotates the ratchet wheel one position.

This rotates the gear wheel, which meshes with a pinion on the previously mentioned stack of five cams. On the very end of the stack is the selector cam lobe with four distinct positions (four selection modes) that drives a rack lever that meshes with the selector display hand. The four individual cam lobes underneath are offset by 90 degrees from their neighbors, taking advantage of the selector cam lobe positions.

Each of these lobes activates an individual lever with a pinion wheel on the opposite end, which pivots into its appropriate gear train, making a connection to the setting mechanism and crown. Thus a very compact mechanism is able to display four choices and simultaneously activate four different gear trains.

Aside from the complicated gear trains, there are anti-backlash features built into the wheels with springs or unique teeth profiles scattered throughout the movement. This isn’t even a feature, really, but a very technical detail that does not surprise me coming from a man that developed a once-thought-improbable complication like a global sunrise/sunset watch.

Krayon Everywhere: design thoughts

All of Maillat’s time and energy paid off and in a big way. Or should I say, “appropriately sized way.”

Maillat spent a large amount of energy working with his component suppliers to develop a movement that was specifically not a behemoth like such things can become. The movement itself is less than 36 millimeters in diameter and a rather svelte 6.5 millimeters in thickness.

Cased up, the watch is a very wearable 11.7 millimeters high, not an ultra-thin but definitely a “normal” thickness, especially considering its ultra-complexity.

It is details like those that tell the real story of a desire to build a fantastic timepiece. The dimensions of the movement and resulting case size show that consideration didn’t end at the mechanism.

The design of the dial, while always a somewhat subjective topic, is still a very clear and intuitive layout, keeping it from getting too crowded like so often happens with ultra-complicated pieces.

Krayon Everywhere

The displays are easy to read, the contrast helps with legibility, and the subdials don’t feel jam packed to the point of uselessness. The entire layout seems to have been honed and reduced until it functioned in the best way possible.

The Krayon Everywhere movement is finished to a pleasing level

Turning the watch over, we see the movement is finished well but not to the highest level of decoration and the number of finishing styles was deliberately kept minimal for clarity. So often on pieces like this, brands decide that doing everything to 110 percent is the only option, not considering that often the best design is when there is nothing more you can take away.

And so for me, the only thing that I could see being removed from the original model (not including the custom engraved or jeweled version) might be the latitude and longitude engraving on the dial.

I know it makes thematic sense, but I feel that it doesn’t add as much as it should. That is just my opinion, though, and it definitely does not hurt my enjoyment of the Everywhere: it is too awesome to be sullied by some engraving I don’t prefer.

View though the display back of the Krayon Everywhere

Because, in the end, I am still always about the mechanics. And this watch delivers it with extra to spare. It has four differentials for crying out loud, and they aren’t just combining four tourbillons (sorry, Roger Dubuis), but allowing you to calculate sunrises and sunsets across nearly the entire world.

If I had to debate whether it was a successful design/product, I could find no issues to raise. Well, maybe one: the price tag. Not because it isn’t deserving, it definitely is a valuable watch, but because it means I will only ever look from afar – as will pretty much everyone else.

For approximately 600,000 Swiss francs, I could buy a couple houses in countries around the world and experience their sunrises and sunsets at my leisure. Not that I wouldn’t want it; it is surely on my list of drool-worthy timepieces.

But after all is said and done, my favorite part about the Krayon Everywhere is that it gave me a case of mind ache, and that is something that doesn’t happen often with a new timepiece. It really pushed me to understand what was going on, and how it was working.

I wouldn’t say I have more than a basic understanding of the mechanisms and how they function, but I definitely can grasp it in mental chunks as my sequential thought processes kick in. From there on in, well, I’m working on it.

Krayon Everywhere front and back

The surface of the watch is a mask of simplicity, but the internals are something else. It tickles both my amygdala and my frontal cortex, inciting passion and curiosity with a payoff that is definitely worthwhile. Bravo to the people that brought it to life, I look forward to seeing what is next!

Let’s break it down!

- Wowza Factor * 9.89 There is barely any room for increased wow factor with a watch and movement like this one!

- Late Night Lust Appeal * 110.11 » 1,079.810m/s2 The amount of mental exercise this watch gave me was more than enough to keep me lusting all night!

- M.G.R. * 72 The Krayon Everywhere gets a perfect score for the movement because . . . do you even need to ask at this point!?

- Added-Functionitis * Extreme This is a watch that makes you scared you caught something serious it has such a stupendous set of added functionalities. It definitely requires a double dose of prescription strength Gotta-HAVE-That cream to ensure the horological swelling doesn’t result in the loss of a limb!

- Ouch Outline * 13 Stepping on a Lego! Not many watches get to this level, but I would walk on a treadmill of Legos if it meant getting a Krayon Everywhere to strap on my wrist!

- Mermaid Moment * It shows sunrise and sunset everywhere?! It really only takes knowing what it does to make you fall head over heels for the Everywhere and send out invites for the inevitable ceremony!

- Awesome Total * 892.5 Multiply the number of components in the movement (595) with the number of days in the power reserve (3) and then divide the result by number of disks in the sunrise/sunset display (2), and the result is one seriously mind ache inducing awesome total!

For more information, please visit www.krayon.ch.

Quick Facts Krayon Everywhere

Case: 43 x 11.7 mm, white gold

Movement: automatic Caliber Universal Sunrise & Sunset (USS)

Functions: hours, minutes; sunset and sunrise, month, date, longitude, latitude, UTC, function indicator

Price: CHF 600,000

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

OMG. Amazing watch. But price point is ridiculous. Are they planning on selling one watch and retiring? I was thinking 20-30k and would be a ‘maybe’ watch for the display, but…

I think it’s more ridiculous to buy this genious idea and execution by just 20-30k.

OK (-ish) – for the man who has everything else. Look, it’s clever – so is calculating the 1,000,000,000th prime number – but, seriously, who has a use for this?

I am glad Joshua managed to get his hands on this piece. Now I actually understand how it works!

The price is very high but considering it took 4 years of work and it’s one of a kind – is it?

Great watch, great article! I loved the detailed explanations & the expanded views…