Along with the arch, columns are some of the oldest standardized structures in architecture, a most basic building feature for supporting a roof without building a solid wall. Thanks to the Greeks, we have a set of rules governing the shape, size, and proportions of architectural columns, which has been passed down for the past few thousand years and was added to by the Romans, later codified in the Renaissance as the five classical orders.

Many architectural periods added to them with their own variations, joining complexity and design to showcase skill, craftsmanship, and wealth. Designs became more intricate over the centuries, culminating with both the earlier Romanesque (tenth to twelfth centuries) and later Baroque and Rococo (seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) architectural styles.

Romanesque took place nearer the end of the classical era (Gothic was its true end in my opinion) before the Renaissance in which pretty much every classical style was rehashed, reconfigured, and revived. The classical Romanesque took a more geometric approach compared to the later Baroque and Rococo, at times creating various patterns in the columns other than the normal fluted or smooth shafts.

Most interestingly, Romanesque also saw the creation of segmented columns taking two main forms: alternating geometric with square and round sections stacked the length of the column (a perfect example being the Romanesque revival building of the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans) and decorated round with several sections of different carved patterns progressing up the column, often separated by either simple column base details or small yet highly decorated dividing sections as exemplified by the architecture of the British Natural History Museum’s facade.

And it is these very segmented Romanesque columns that were my first thought when I initially saw the Hysek Design Colonne du Temps, an impressive mechanical clock built in the format of a segmented column displaying the time vertically.

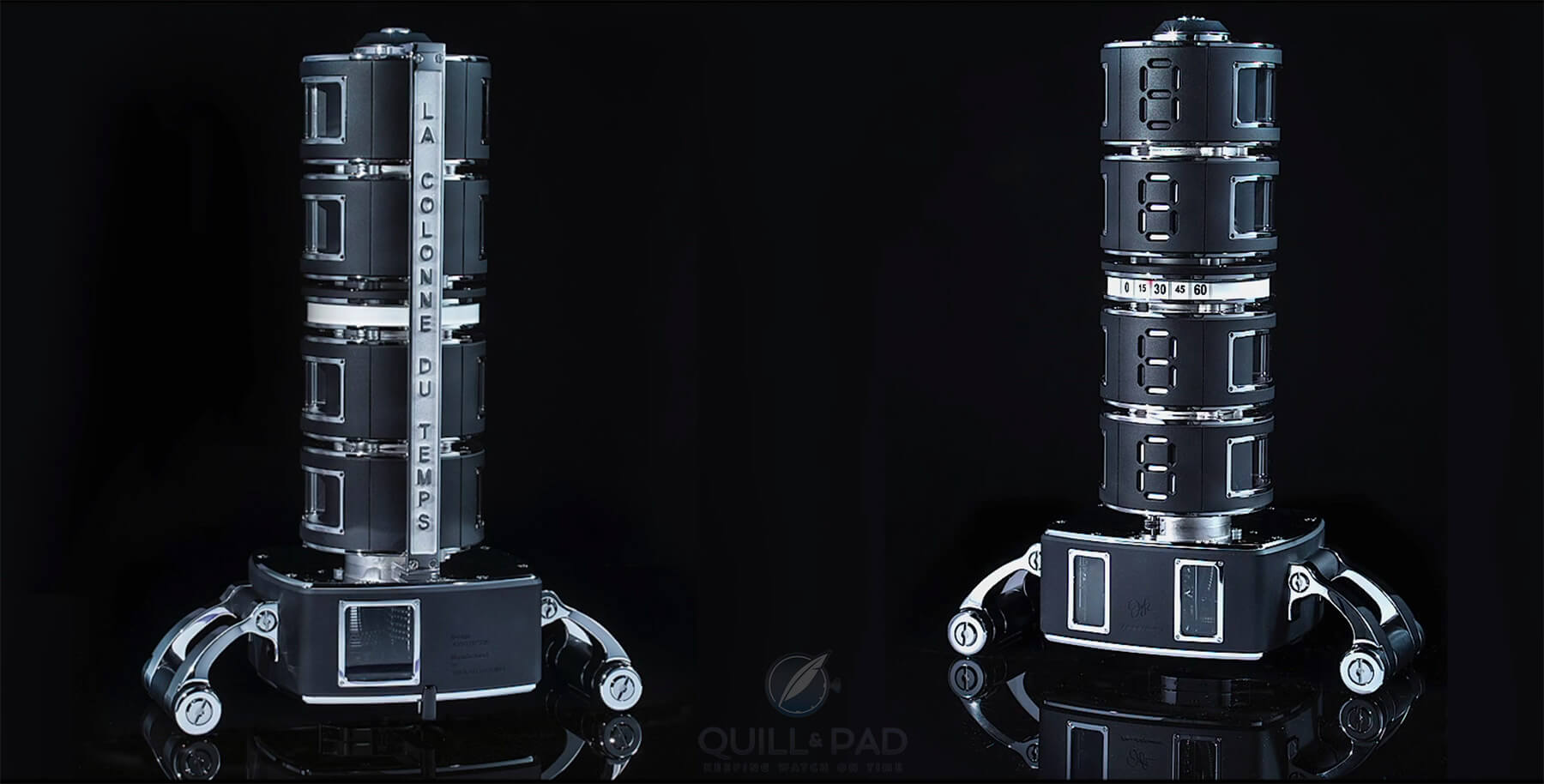

Two views of the Hysek Design Colonne Du Temps (image courtesy Hysek Design/Clayton Creative)

Hysek Design Colonne du Temps

The resemblance between the Hysek Design Colonne du Temps and a Roman column is more than just fleeting, and since it even has the word column in its name the connection couldn’t be more obvious to me. Released at Baselworld 2018, it marked the return of Jorg Hysek, a prolific watch designer and founder of an eponymous brand who has spent the last two years sailing his boat in quasi-retirement.

Of course, Mr. Hysek couldn’t turn his creative mind off and so the development of the Colonne du Temps began in earnest after a discussion with clockmaker Sinclair Harding, who manufactures this stunning clock.

Ideas become mechanical reality

While the inspiration for Mr.Hysek isn’t clear, I can’t help but feel that, at least subconsciously, Romanesque columns had some influence over the design. Jorg Hysek had a concept that formed over time and spoke with various manufacturers about the possible viability of the idea.

As happens when anything new is suggested, Jorg Hysek received hesitation and pushback over the concept, suggesting that it might not really be possible. After speaking with Robert Bray of Sinclair Harding, who, according to Mr.Hysek, is “also a little bit crazy,” a plan was made to develop the column of time concept into a real mechanical masterpiece.

Hysek Design Colonne Du Temps (image courtesy Hysek Design/Clayton Creative)

The Colonne du Temps concept focuses on six segments, five of which tell the time and one of which houses the movement. The time is displayed in two large segments divided from another two large segments by a thin segment featuring the running seconds display. The layout is as far from a standard clock as possible and yet it feels sort of inevitable, like the idea was just waiting for the right creative mind to put it into action.

The main movement is found in the base, an eight-day fusée and chain-driven masterpiece wound via a lever extending from underneath the lugs. Yes, you heard that right, this clock has lugs: the base segment sits up off the table thanks to legs shaped like watch lugs, an appropriate touch from a designer that has spent his career working almost exclusively on watches.

Watch lug-like legs and movement in the base of the Hysek Design Colonne Du Temps (image courtesy Hysek Design/Clayton Creative)

Every segment has multiple windows into the mechanisms inside allowing the entire ballet of gears, cams, and levers to be viewed. Each segment displays a different numeral, with the time being read from top to bottom.

The upper segment shows the tens of hours and below that are the hours. In the center is a small segment with a running seconds display with sweet retrograde action. Moving down, the fourth segment (third large segment) displays the tens of minutes and below that are the single minutes.

Simplicity from complexity

But how does it all function? The answer is relatively simple: cams, lots and lots of cams. The movement includes more than 20 cams, with each digital display requiring five cams just to adjust each numeral’s appearance.

But I am getting ahead of myself. The power for the clock comes from the base segment, which drives shafts up through the individual segments and to the central running seconds segment. The mechanism inside the center segment is a retrograde second display that features a snail cam releasing the mechanism after each minute to fly back to zero.

At the same time, a geared jumping mechanism on the base segment drives the majority of the rest of the displays. The base segment does the most changing while the upper segments change much less often, so this is the obvious choice. A a series of shafts connects each segment so that each changes display at the right time.

The function of each segment is similar, with the main differences being the gearing ratios for activation. The basic operation sees a shaft with a ratchet wheel on the bottom activated at the jump of each minute (or tens of minutes, hours, or tens of hours respectively). This shaft has five cam wheels interacting with the display levers thanks to a channel milled into each. A small pin rides inside the channel that is attached to one of the display levers. The levers pivot with each change in the cam position, continually changing the display.

Hysek Design Colonne Du Temps

The time presentation is based on a seven-segment display requiring numerous openings that change at different times. Each display has seven of these openings, four vertical and three horizontal, which allow them to alternate between black and white (accomplished via painted screens behind the segment wall).

These screens attach to the levers and pivot back and forth to display a different configuration for the openings. Each level in the display is controlled by one lever, meaning two vertical openings are driven by one screen requiring four positions, while the horizontal openings only require two positions. This method improves upon other brands’ attempts at a similar display style, largely thanks to the available space to operate in.

The symmetry of the segments is underscored by the outward simplicity of the shape: a simple cylinder with a single number on one side; it can’t get much simpler than that. Of course, the windows into the mechanisms remind you that this is clearly a complicated creation; from a distance, the visual effect is stunningly simple.

You might even be convinced that it was electronic or digital if you saw it across a room without up-close inspection. That comes down to good design: the shapes flow well together yet are different enough with their separations that they promote visual movement from the sturdy and substantial base moving up the column to the very top.

It clearly is very avant-garde, and that is one of the main reasons I liked it when I first saw it.

But what truly hooked me was the mechanism, the pure and logical cam systems driving a deceptively simple seven-segment display, which puts into stark relief that just because something has been tried before doesn’t mean it was done as well as it could be.

While many watch fans may not look at clocks with the same zeal (unless they are made by the star power of MB&F), I feel like this clock goes down the right path in pushing the edges of mechanical creativity and may just be the start of something far greater.

So let’s break it down!

- Wowza Factor * 9.4 Interesting clocks always have a chance at wowing crowds, and the Colonne du Temps doesn’t disappoint!

- Late Night Lust Appeal * 92.8 » 910.057m/s2 The power of this piece to keep people lusting all night is due to its incredible construction and mechanical awesomeness!

- M.G.R. * 66.8 The complexity of the movement belies how simple the concept is in theory and stands out as a mechanical gem!

- Added-Functionitis * N/A Another time-only creation that surely doesn’t seem like something simple when you really look at it. Still, there is no need for Gotta-HAVE-That cream even though I still gotta have that!

- Ouch Outline * 11.8 Squishing the tip of your finger under 250 pounds of urethane foam! Yes, foam can be really heavy if the density is high, and a three-inch-thick, four-foot-by-eight-foot sheet of 31-pound density is a beast. So of course, while moving it at least one digit will get nearly crushed. Still, I wouldn’t hesitate to take that pain again for a chance at having the Colonne du Temps on my desk!

- Mermaid Moment * One minute! With the function of the Colonne du Temps being a jumping minute and hour, it doesn’t take much time to fall deeply for this masterpiece. It actually takes longer to figure out a seating plan and select the caterer!

- Awesome Total * 968 Add the weight of the clock in kilograms (15) to the number of components in the clock (953) and the result is a heavily awesome total!

For more information, please visit www.hysek-design.com/en/produit/la-colonne-du-temps.

Quick Facts Hysek Design Colonne Du Temps

Case: 40 cm tall, 11 cm in diameter, anodized aluminum

Movement: manual winding (key) Sinclair Harding movement with 953 components, chain and fusée

Functions: jumping hours and minutes, retrograde seconds

Limitation: 55 pieces

Price: 60,000 Swiss francs

* Please note that Hysek Design and Jorg Hysek have no current personal or business relationship with the brand Hysek.

You may also enjoy:

Word For Word: Qlocktwo Presents A New Approach To Telling The Time

The Magic Is In What You Don’t See: MB&F Destination Moon Clock With L’Epée 1839

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!