by Ian Skellern

As with most things in my life, I came to Breguet late. My horological interest was the independents; the large brands were really a sideshow for me.

But when my wife, who until then had expressed little interest in haute horlogerie, decided that she would like a nice watch, it became quickly apparent that the decision wasn’t about which brand, but which Breguet.

That that was an eyeopener about the power of the name.

And if you are curious, she ended up choosing a Breguet Marine.

Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747-1823) is considered the greatest and most influential watchmaker in history thanks to his horological inventions and innovations, many of which the industry still cherishes and produces in large quantities today – including the tourbillon, repeater gongs, automatic winding, balance shock protection, balance spring overcoil, and sympathetic clocks (okay, the latter perhaps not in any sort of quantity).

But what really made Abraham-Louis Breguet’s reputation was that his technical genius was complemented by an excellent sense of design plus superb management and marketing skills.

While born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, Abraham-Louis Breguet worked and created most of his watches and clocks in Paris. He went to Switzerland briefly in 1793 at the start of the French revolution, returning to Paris two years later when the politics had stabilized.

Breguet and The Naked Watchmaker

The Naked Watchmaker (TNW), aka Peter Speake-Marin, has recently began a series of deconstructions of a broad selection of modern Breguet watches and movements, starting with the Classique 5177, a relatively simple (for Breguet) three-hand dress watch with date.

Breguet Classique 5177

While I very much appreciate and learn from the deconstructions on The Naked Watchmaker, I wanted to find out a bit more. So here are a few things that The Naked Watchmaker didn’t tell us about the Breguet Classique 5177 that you might find as interesting as I did (use of Speake-Marin’s excellent photographs with permission).

Breguet Classique 5177: essentials

While the Classique 5177 is a relatively uncomplicated wristwatch – as a dress watch should be – it’s worth highlighting that it is often the apparently simplest things that require the most attention as there is little to hide or distract from any perceived flaws.

Breguet Classique 517 dial and movement sides

The basics include the display of hours, minutes, (hacking) central seconds and a date window, a hand-guilloche 18-karat gold dial, tempered steel pomme-shaped hands (generally known to enthusiasts as “Breguet hands”), a three-piece clip case, and a coin edge case band. It is powered by automatic Caliber 777Q with a free-sprung silicon balance spring and a hand-guilloche solid gold rotor.

Breguet Classique 5177: hand guilloche

While the modern Breguet is known for many different styles, techniques, and finishing, one stands out above all others: guilloche dials.

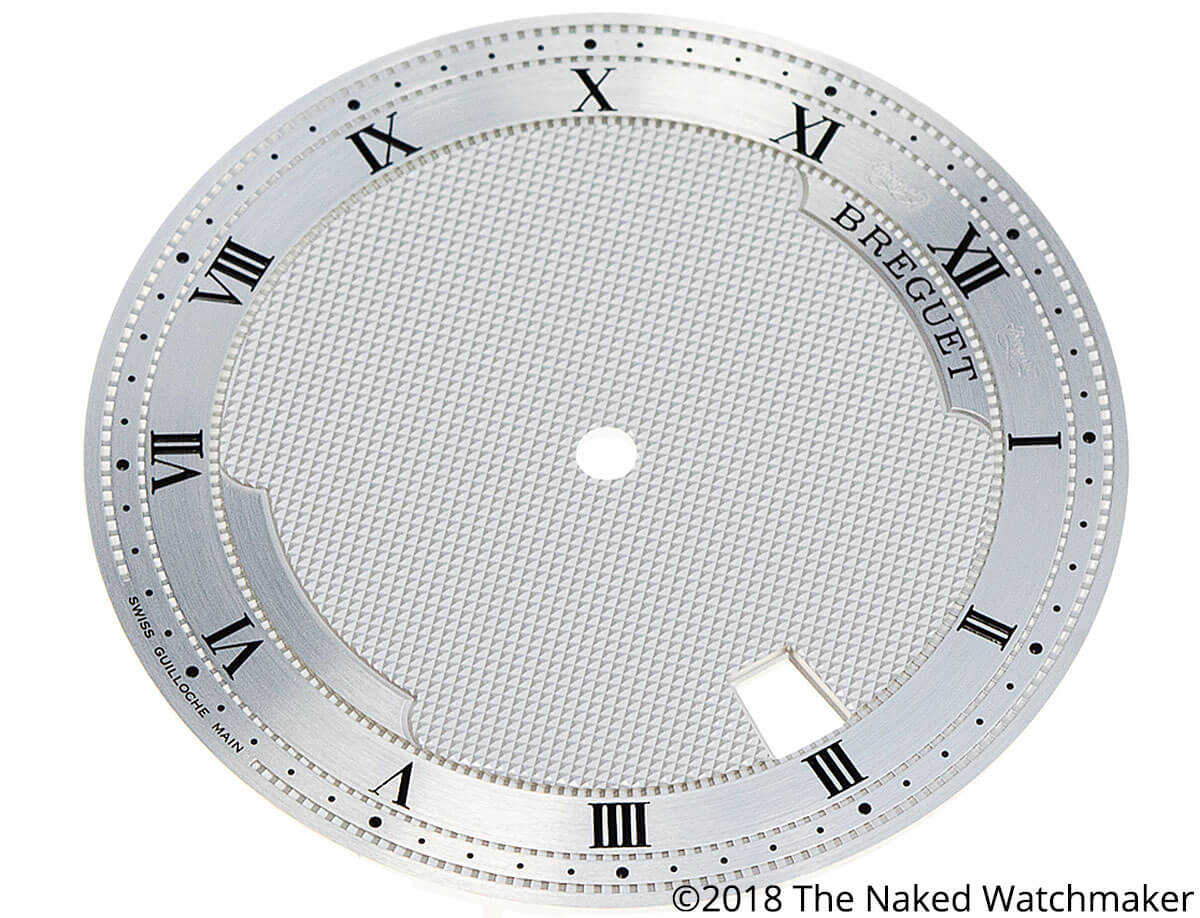

Hand-guilloche dial of the Breguet Classique 5177

Guilloche is a decorative technique dating back to the sixteenth century comprising decorating an object with finely engraved lines. At the beginning, guilloche was mainly used to embellish relatively soft organic materials including ivory, soft stone, wood, horn, and even coconut shells.

Around 1786, Abraham-Louis Breguet started using guilloche to decorate his dials and watch cases, and from that time onward the popularity of the finish steadily grew and evolved with more intricate patterns on more complex surfaces.

My introduction to high-level hand-guilloche began inauspiciously more than a decade ago with a visit to an atelier on the ground floor of a residential apartment block in Geneva. I had gone to visit the guilloche workshop of a certain Mr. Tille, a master of the art, who Daniel Roth had entrusted to guilloche the quite complex dial of one of his Jean Daniel Nicolas Two-Minute Tourbillons that a friend of mined had commissioned. I wanted to see how it was done. (For more on that watch, see The Watch That Changed My Life: The Jean Daniel Nicolas Two-Minute Tourbillon By Daniel Roth.)

On arrival, I thought that I must surely have the wrong address. After knocking on a few doors, I found Tille in his office surrounded by old motorbikes and even older machines, none of which seemed to have the slightest connection to guilloche.

However, when I expressed to Tille my surprise at the lack of the large machinery I was expecting, he smiled and beckoned me to a closed door in his office, which opened to reveal a surprisingly large room filled with many guilloche machines. The noise of them working and the smell of oil told me for the first time I was in the right place.

The reason for the lack of machinery in Tille’s office was that he had retired. The workshop was now being managed by his son Daniel, and the rose engines (for circular and curved patterns) and straight-line machines were busy engraving special dials for the biggest names in the business.

Jean Daniel Nicolas Two-Minute Tourbillon by Mr. Daniel Roth in pink gold (photo courtesy Guy Lucas de Peslouan)

I followed the process for setting up and engraving the dial of the Two-Minute Tourbillon I had come for and left a little bit wiser. Roth had spoken very highly of Tille’s guilloche, and I now had a better understanding of what was involved.

A few years later I learned that Tille’s Geneva atelier had closed down. The reason: in 1999, Swatch Group chairman Nicolas G. Hayek had bought Breguet and planned to make it the crowning glory of the group. And guilloche was a significant part of his plans.

He made an offer to Daniel Tille to move from Geneva up to the Vallée de Joux with his staff and machinery to teach Breguet and bring the art of handcrafted guilloche in-house.

Breguet restores and modernizes guilloche machines at the manufacture in Swizterland

The story I heard was that it was supposed to be a three-year project, but now more than ten years later Daniel Tille is still at Breguet. And, not surprisingly, Breguet is once again making superb handcrafted guilloche.

Hand-guilloche solid gold rotor of the Breguet Classique 5177

And not just the art of guilloche itself: Breguet also makes its own guilloche machines, often based on very old examples that the brand finds, restores, and modernizes.

Breguet takes guilloche very seriously.

A few of the rose engine guilloche machines and team members at the Breguet manufacture

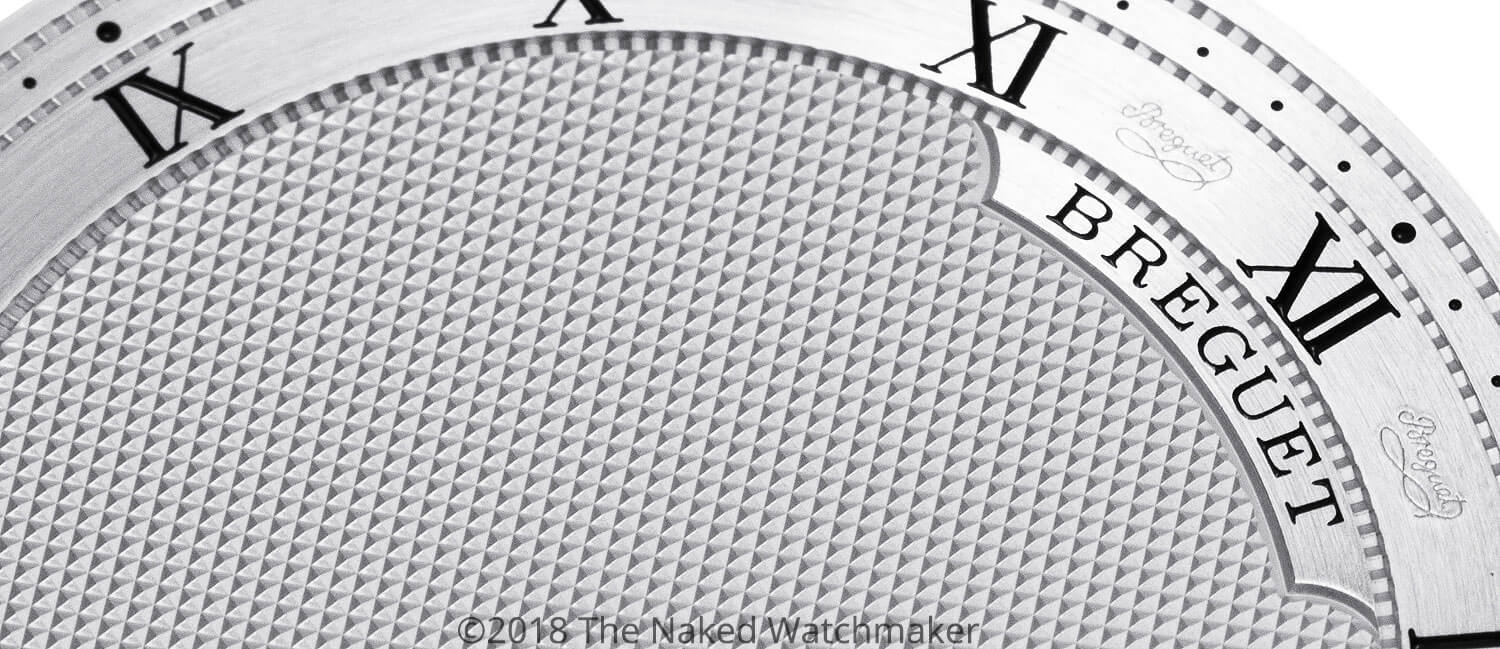

And then there’s the Breguet secret signature that is all but invisible to the naked eye.

The secret signatures are only visible under high magnification, here either side on the XII; A-L Breguet introduced his secret signature to help foil fake copies of his watches (which was already a problem 200 years ago)

Which is all a long way of saying, please take a good look at the relatively simple, unadorned guilloche dial of the Classique 5177 and appreciate how much work went into this one component.

Breguet Classique 5177: hacking seconds

“Hacking” is a horological term that denotes the ability to stop the second hand while the crown is pulled out to more precisely set the time. Hacking is usually achieved by stopping the balance wheel from oscillating by applying some type of break. Because hacking mechanisms are usually out of sight under movement plates and bridges, the majority of hacking mechanisms are simply a single flat piece of stamped-out metal.

The hacking mechanism of Breguet Caliber 777Q, on the other hand, is comprised of six different machined components, all of which are all nicely hand finished.

‘Golf club head’ hacking seconds balance wheel break on the Breguet Classique 5177 Caliber 777Q

The “golf club” balance wheel brake is worth highlighting here: a lot of work has gone into this small mechanism that few will ever see. The hacking mechanism wasn’t made to this level to show off, as it can’t be seen. It was done well because the basic approach appears to favor horological quality over cost-cutting.

Conclusion

While at $28,700 the Classique 5177 is by no means bargain basement, the attention to detail reflects a level of thought, care, and execution usually reserved for much more expensive timepieces. And perhaps even more importantly, the movement, like the solid gold (rather than silver) dial with invisible secret signature as well as the hand-guilloche gold rotor, are all consistent with Abraham-Louis Breguet’s approach more than 200 years ago to creating innovative, high-quality watches.

Easy-to-use strap bar locking screws (rather than simple spring bars) on the lugs of the Breguet Classique offer further evidence of thoughtful attention to quality

On The Naked Watchmaker, Speake-Marin goes into much more detail with an absolute plethora of macro photos of all major and minor components of both case and movement in his Breguet Classique 5177 deconstruction.

Breguet’s automatic Caliber 777Q powers the Classique 5177

For more information, please visit www.thenakedwatchmaker.com/decon-breguet-classique-5177 and/or www.breguet.com/en/timepieces/classique/5177.

Quick Facts Breguet Classique 5177

Case: 18-karat yellow gold, 38 x 8.8 mm, sapphire crystal case back

Movement: automatic Caliber 777Q, silicon free-sprung balance spring, 55-hour power reserve, 4 Hz/28,800 vph frequency, 243 components, Swiss straight-line lever escapement

Functions: hours, minutes, hacking seconds; date

Price: $28,700

You may also enjoy:

- Breguet Marine Alarme Musicale 5547: Keeping Technological Traditions Alive

- Breguet Classique Tourbillon Extra-Plat Automatique 5367 Grand Feu Enamel: What A Difference A Dial Makes

- The Breguet A2: It Does Up To 40 Kilometers Per Hour And Doesn’t Tell The Time

- Battles Of Breguet Part One: Conquest Of The Seas

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

As far as guilloche dress watches go, Breguet’s Classique range is one of my favourites, along with Urban Jurgensen’s 1140 selection, and FP Journe’s Souveriane models.

That’s a good selection, Gil, our tastes in guilloche coincide.

Regards, Ian

Thanks, Ian. Mind you, if only Breguet made brown or dark grey guilloche dials for some of their Classique range, I’d forget all about Jurgensen and Journe. My 5157 is the only silvered guilloche I need.

C’mon Breguet, make the 5277 in brown or dark grey. Pleeeease.

My two cents:

1. My UJ’s brown guilloche dial looks less prominent under a sub-optimal light or greater distance.

2. In my humble opinion, UJ’s guilloche dials are not inferior than Breguet’s, but UJ’s hands are way better than Breguet’s.

Hi Chia-Ming, I never knew it was the brown Jurgensen you had (I knew you had a 1140 from comments on Monochrome); beautiful piece, you’re very lucky. Thanks for letting me know about the reality of the brown dial – that’s something I suspect most coloured guilloche dials may suffer from. But you know, that’s still OK with me..

Have you seen the Voutilainen Vingt-8 with brown guilloche? There’s one on ‘A Collected Man’, and it seems to look amazing in the wrist-shots.

Thank you! Enjoyable read on a very specific, but beautiful subject. Was fortunate enough to see Breguet exhibit in San Francisco a couple years ago. Amazing.

I had the good fortune of visiting the Breguet exhibition in Switzerland, Anthony, and I also thought it was sensational.

Regards, Ian

Great article. I’ll miss their display at Basel this year. Last year they actually had one of the rose engines in their booth where you could try guilloche for yourself. That was the highlight of the show for me!

I agree, Ray, there is no better way to appreciate how difficult intricate guilloche is than trying it yourself. The machines are really just tools guided by hand rather than automating the process, and the work requires intense concentration.

Regards, Ian

@Gil

Thanks for your kind words. Yes, after more than one year of ownership, I am still deeply fascinated by its beauty and it also gets my most wrist time.

I haven’t seen any brown guilloche dial Voutilainen in real, but from the photos of “A Collected Man”, I guess they are quite the same(from what I know, UJ’s dials are produced by Voutilainen). They will still shine under a good light, but be rather understated under a muted light.

Well I learn something new every day – I didn’t know that Voutilainen/Comblemine made UJ’s dials. Always a good thing.

What I did know (at least I think it’s true) is that Voutilainen is involved with Chronode – who make the P4 movement in conjunction with UJ – and he supervises the finishing of the calibre.

It’s my turn to learn it, I don’t know Voutilainen has supervised the finishing of the P4 movement. But frankly speaking, I rarely care about the movement because most of the time it is on my wrist and its dial, hands even case catch all my attention.

Wonderful article, Ian! Breguet’s guilloche is extraordinary and I am pleased that Daniel Tille is still in the shop teaching and keeping the art alive. The Le Réveil du Tsar 5707 is one of my favorite timepieces. I love the way all the various guilloche techniques are perfectly integrated on a single dial.