The Schmidt List: Signature Movement Screws – Reprise

by Ryan Schmidt

The components of a mechanical watch movement are little more than a series of springs and wheels, held together by plates and/or bridges. No matter the configuration, complication, or finish, the ensemble is secured by the humble movement screw.

Although the movement screw is among the more ubiquitous of horological components, its simple properties and purpose don’t offer the watchmaker an abundance of opportunities to demonstrate their creativity and flare. Nevertheless, etching creativity and flare into some of the most obscure and unexpected places is what some of the best watchmakers seek to do; and so, it’s a pleasant surprise that several have boldly ventured beyond thread and slot to reimagine the movement screw.

This installment of the Schmidt List covers a handful of particularly unusual movement screws. And by “movement screw,” I refer to the screws found within the watch case, not upon it.

However, before we jump into the exotica let us first satisfy the conservative purist by considering the classic screw.

Ultimate classic slotted screw

It’s hard to imagine a purer movement screw than one made according to the George Daniels method of watchmaking. The heat treatment of such a screw gives rise to a purple hue, and the gentle curvature of the head is delectable. Of all these “Daniels” screws, the extra-tall balance cock screw, found on the Daniels Anniversary Watch movement among others, is king.

Note the classic balance cock screw in the Daniels Anniversary Watch movement

The collaborative project known as Le Garde Temps – Naissance d’une Montre brought watchmakers Robert Greubel, Stephen Forsey, and Philippe Dufour together to instill in one pupil, Michel Boulanger, the dying art of traditional watchmaking by hand. The first fruit of their labor was the “School Watch,” a magnificent living documentary of the techniques.

The production version of Naissance d’Une Montre, Le Garde Temps on display at SIHH 2016

Unsurprisingly, the Le Garde Temps contains a host of exemplary components, but let’s just take a moment today to admire that tourbillon cock screw.

Like the Daniels Anniversary Watch screw, it stands tall and proud, but in the School Watch it is perhaps even more special as it is the only heat-tempered screw on the watch, the deep blue accent resonating with the hands of the main dial and subsidiary seconds. Unlike the Daniels, it doesn’t have a large cylindrical head, instead featuring a more regular head with a collar further down its shank.

There are other blued movement screws that equally catch the eye, not because they stand tall but because they sit wide and deep within a beautifully chamfered countersink.

F.P. Journe Tourbillon Historique T30 tourbillon bridge

It’s hard to imagine a better example than that seen behind the hinged case back of the F.P. Journe Tourbillon Historique T30. Five giant blued screws secure the bridges for the tourbillon, the twin spring barrels, and the center wheel. The proportions of these beautiful oversized screws are further exaggerated by a sprinkling of tiny screws for the chatons and other components.

The strong shine of classic screws on the Voutilainen Vingt-8

Finally, if it’s a strong shine you seek from a classic screw, you might prefer yours not to be tempered. When combined with the large frosted or striped plates of a manually wound movement, a set of well-polished screws can become decorative highlights. Take the superbly polished and chamfered screws on a Voutilainen Vingt-8, including the very large ratchet wheel screw that is visually beaten only by the oversized 2.5 Hz balance.

Cross-slot screw

While commonly used in our everyday lives, it’s surprising that cross-slot screws are rarely featured in watches. And so they certainly jump out when MB&F presents two large polished cross slots holding the sapphire crystal tourbillon bridge of the LM1 Silberstein.

Check out the large cross-slot screws holding the visible sapphire crystal bridge on the MB&F LM1 Silberstein in red gold with frosted “dial” (actually the movement’s top plate)

A mix between a true cross-slot and a Phillips screw, these two beauties are the perfect addition to an already quirky mechanical design.

I liken it to a strong tartan pattern on a tweed jacket.

Triple-slot screw

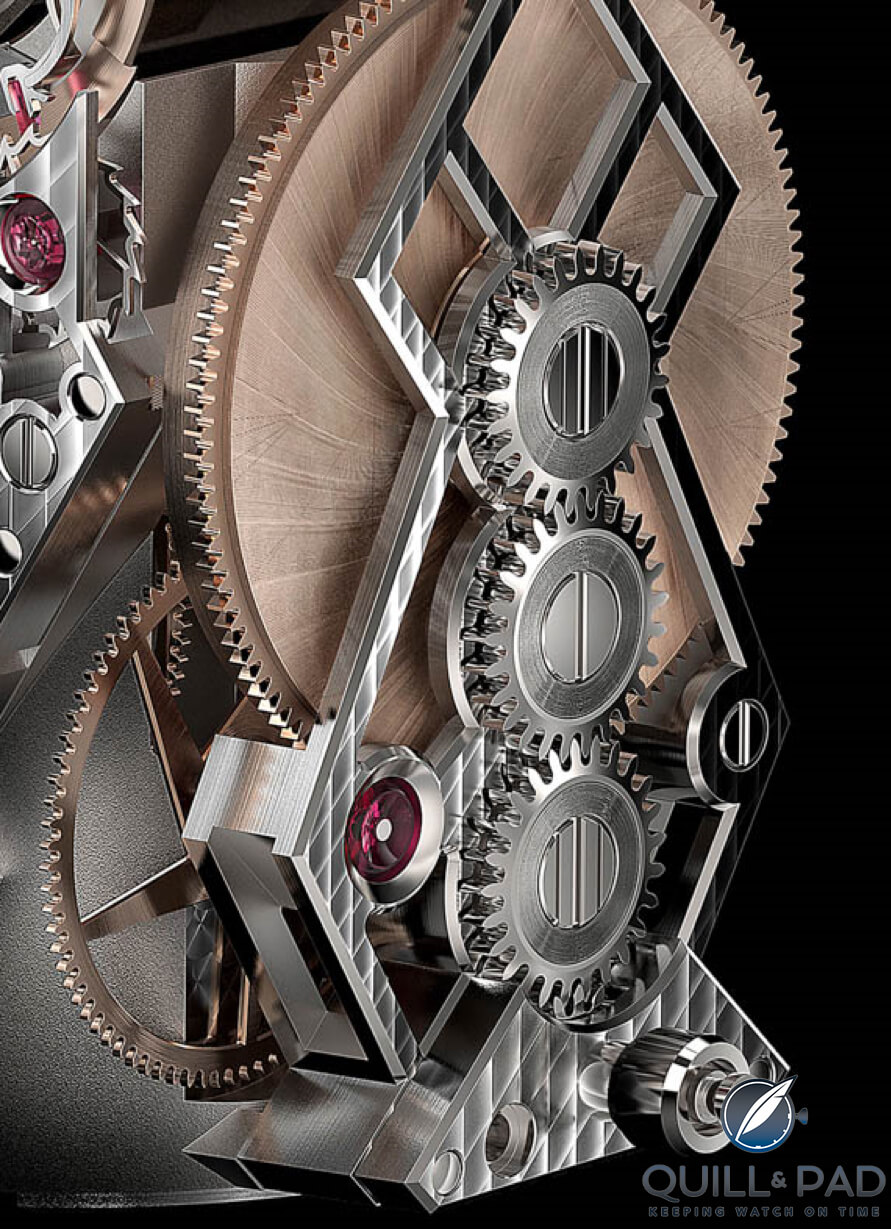

From the foundation of a basic single-slot screw, the simplest way to upgrade is to cut two parallel slots on either side of the functional one. In doing so, the surface achieves a somewhat sporty and contemporary aesthetic. The triple-slot screw can be found on the ratchet wheels and intermediary winding wheels of some of the most pioneering of contemporary movements, from the HYT H2 Tradition to the Angelus U20 Ultra-Skeleton Tourbillon.

Look closely to see the triple-slot screws on the intermediary winding wheels of the U20 Ultra-Skeleton Tourbillon by Angelus

But the triple-slot buck stops with Dominique Renaud’s staggering DR01. More of a mechanical sculpture than a movement, the DR01 features a revolutionary escapement housed within truly avant-garde architecture.

The triple-slot buck stops here: Dominique Renaud’s staggering DR01

It’s easy to overlook the two triple-slot screws among some of the most unusually presented and seemingly alien mechanics.

* Update February 1, 2018: Thank you to the numerous attentive readers for pointing out in the comments below that the triple slot is not primarily an aesthetic choice, but rather indicates that the screw is reverse threaded and requires unscrewing in a clockwise direction, e.g. mainspring barrels.

Curved-slot screw

Surveying the spokes, bridges, and plates of a watch by Romain Gauthier, one might notice an absence of straight lines. Instead, the contours of every structural and aesthetic element flow in sympathy with the wheels and rotors beneath, a strong sign that the movement has been designed and built in-house from the ground up.

It’s particularly apt, therefore, that Romain Gauthier should extend this approach even to his screws.

Do you see the curved-slot screws on the winding system and power reserve of the Romain Gauthier Logical One?

The Romain Gauthier curved-slot screw (or “coffee bean screw,” as I call it) is visually refreshing and simple yet deceptively harder to execute than one might first think. That combination is a great reason for a master watchmaker to further forge his identity into each component, the accumulated effect exceeding anything that could be mimicked by competitors with an appetite for corner-cutting.

Perhaps more applicable to an exotic case screw, there is also a security angle to such a move: exotic screws often require bespoke drivers to be built. A friend once showed me a listing for a particularly rare watch being offered for a staggering discount on the market value – a quick pinch of the screen revealed that a “watchmaker” had decided to service the piece and heavy-handedly opened it with a slotted driver, mashing the slots of the exotic case screws. Buyer beware!

Hex-socket screw

Venturing further beyond the simple slot, some screw heads are carved out, leaving behind a geometric socket and requiring a similarly shaped key to turn it. Such is the case with the hex-socket screw, which is used to secure some very unusual wheels, plates, and dials in HYT’s liquid-indicating H4.

The hex-socket screws are front and center on HYT’s H4 Alinghi (the time shown here is 5:58)

The hex-socket screw has a utilitarian feel to it: the surface is not used to showcase impeccable finish, but instead to evoke the spirit of advanced engineering.

It may also trigger flashbacks of flat-packed furniture, but fortunately the H4 comes pre-fabricated!

Inverse spline screw

Most commonly found adorning the cases of Richard Mille’s creations, there are some occasions that the inverse spline screw is used on the movement, such as the RM 67-01. Instead of cutting a spline slot into the screw heads, the edges are cut to produce an inverse (or male) spline.

The movement side of Richard Mille’s RM 67-01 showcases the movement’s inverse spline screws

It’s another utilitarian effect that no doubt requires some equally utilitarian tools to be developed by the watchmaker in order to screw and unscrew.

Reticle crosshair screw

The final screw is the reticle crosshair. So close to being a simple cross-slot screw, the reticle crosshair is certainly not simple.

Christophe Claret X-TREM-1

Resembling the view of a high-tech rifle crosshair, Christophe Claret uses this screw to hold in place the plates and winding gears of the X-TREM-1.

Venn screw

Found on many case backs of MB&F’s Horological Machines, the HM4 is one of the few to use these screws on the movement. Effectively just three overlapping holes cut into the head, and reminiscent of a three-set Venn diagram, this screw evokes the kind of playfulness that runs deep throughout the brand.

The elegant MB&F HM4 balance cock is held by Venn screws

I would imagine the Venn screwdriver is rather a tough one to create.

Bonus: case screws that just have to be mentioned!

Although this particular Schmidt List was dedicated to the movement screw, one cannot pass this close to the topic of the case screw without being pulled in by its strong gravity.

Here are some of the most notable case screws that have not yet found their way into a movement.

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak bezel screw (nut/bolt?)

And now, deep within the tail end of an unrelated article, it’s time to answer an age-old question: are these really screws?

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Ceramic Perpetual Calendar: are these really screws?

The answer is “no”: they are slotted bolts.

Although Audemars Piguet refers to them as hexagonal screws, they are bolts because a) they do not turn, b) they have threading along the full shank, c) the shank is not tapered, and d) because the bolts engage with receiving screws/nuts on the other side.

Back in 2012, Walt Odets deconstructed a Royal Oak and concluded that they were screws, but this appears to be a conclusion drawn by the presence of a slot and not the other information listed above. Audemars Piguet apparently referred to them as hexagonal nuts back then, so they themselves seem a little unsure of the identity of these iconic components.

While Odets likened the concept of Royal Oak case bolts without threads to a queen without her crown, their threads are nevertheless redundant as the bolt is held from rotation by the countersinks in the bezel. Were they rounded and free to rotate, we would be back into screw territory. But it’s my opinion that the redundant slot is the only ambiguity in what is otherwise a bolt.

Hublot bezel screw

It might well be because Gérald Genta designed the Royal Oak within a matter of high-pressured hours that there is ambiguity as to its exact inspiration. The general understanding is that it was named after the HMS Royal Oak. But the bezel was not based on a porthole (hublot in French), but rather a diving helmet.

That may be the case, but make no mistake here: the Hublot Big Bang was inspired by a porthole (the French word hublot means “porthole”).

Hublot Big Bang Unico Sapphire Usain Bolt Only Watch 2017: those bezel screws, though . . .

This porthole may hold a passing resemblance to the Royal Oak bezel, but unlike the Royal Oak’s nuts and bolts, those are bezel screws. They are turned at their head to affix to a receiver. With the Royal Oak it is the receiver that is turned from its head on the case back.

The Hublot Big Bang receiver has two female ends to receive a set of screws from the front and back.

It’s a powerful aesthetic, but what makes the screws particularly special in my opinion is the subtle “H” that is formed by interrupting the slot in the middle. It’s a double-protected screw, conveying some intellectual property and requiring a two-pronged driver to manipulate it.

Pig-nose / spanner-head screw

Common to the case backs of watches from Kari Voutilainen and Greubel Forsey, the pig-nose screw can also resemble a pair of wide eyes or, in the right lighting, a yin and yang symbol.

Greubel Forsey GMT Earth case back screws

Voutilainen Vingt-8R case back screws

In the case of Voutilainen, the design echoes that of the crown wheel, which is held down by two small screws.

F.P. Journe’s tri groove

F.P. Journe case backs are held in place with the tri-groove screw. That is exactly the sort of security you need for a complicated 18-karat solid pink gold movement.

Gold movement of the F.P. Journe Chronomètre à Résonance

In this series Ryan Schmidt, author of The Wristwatch Handbook, delves deep into horology to uncover, explain, and celebrate the unusual and the exceptional in the world of watches. For more of Ryan’s articles, please see www.quillandpad.com/author/ryan-schmidt.

* This article was first published on February 28, 2018 at The Schmidt List: Signature Movement Screws.

qual o valor watch scoolth?

Cool! Concerning the Royal Oak, I guess the ambiguity is due to the fact that the one with the non-turning head (in front) is the one whith the external thread, while the one with the turning head (in the back) is the one with the internal thread. Not being a native english speaker, I don’t know which one is supposed to be called screw and which one is supposed to be called nut…