Benjamin Millepied is perhaps the most famous choreographer working in ballet today. And the 41-year-old has been a Richard Mille ambassador for many years.

You may have seen Millepied dance with the New York City Ballet (1995-2011) or you may have seen his work in 2010’s Black Swan, where he not only choreographed the Hollywood film’s dance scenes but also danced himself. Of late, you can catch his work in the L.A. Dance Project, with choreography linking classic ballet to modern dance in the same way Millepied’s own multidisciplinary artistry builds bridges to other art forms.

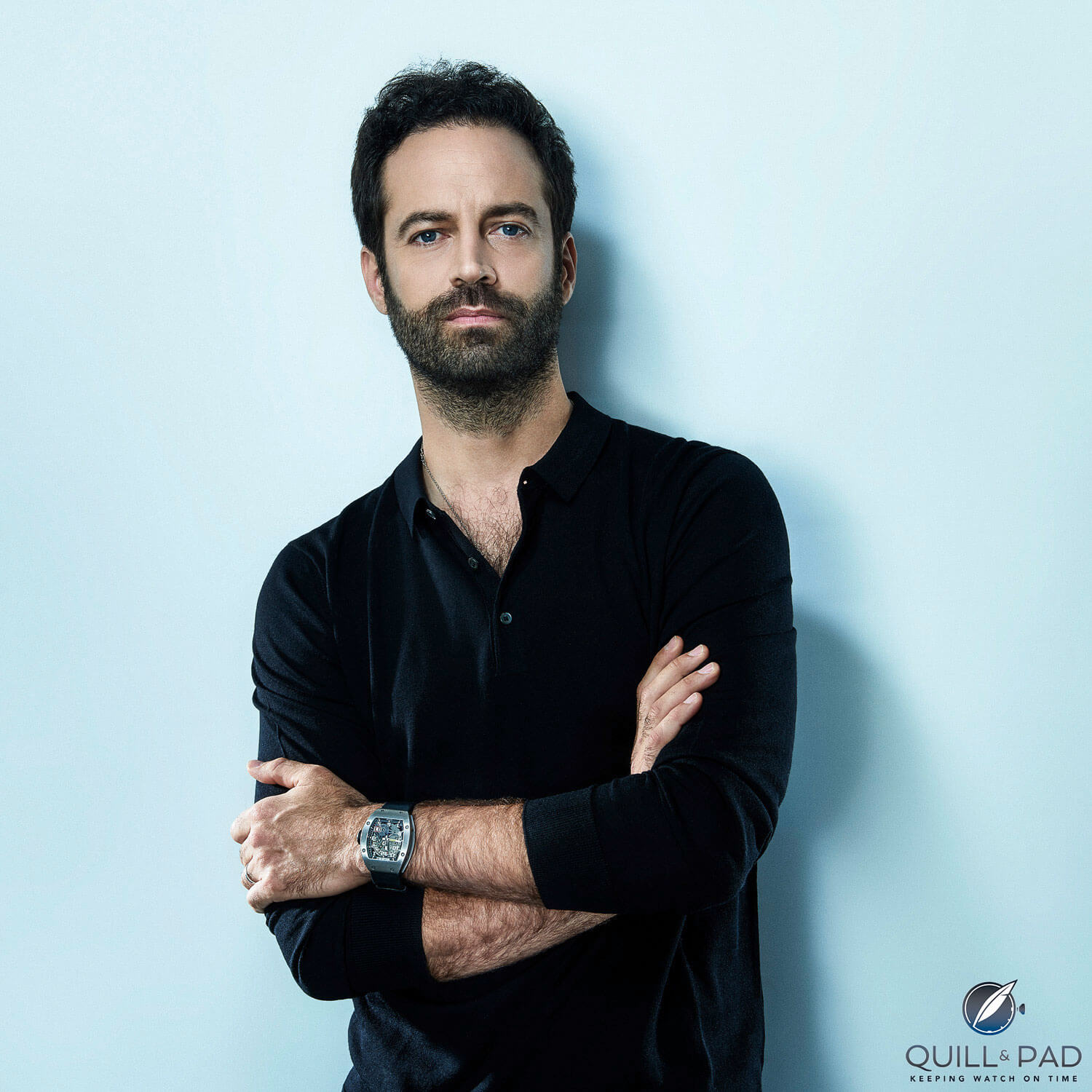

Benjamin Millepied wearing a Richard Mille RM 029 (photo courtesy Richard Mille/Jaso)

The native Frenchman’s L.A. Dance Project has been touring Europe, and thanks to Richard Mille I got a chance to take in one of the shows and have a quick chat with the man before a performance at Paris’s Théâtre des Champs-Elysées.

Millepied wears the RM 029, the first Richard Mille model to feature a large date.

Richard Mille’s RM029

Q&P: How did you meet Richard Mille and become part of the ambassador family?

BM: Well, he was working with [my wife] Natalie [Portman], and both of us being French we got along very well. I think it was a very simple, direct friendship that began and then we just started to work together.

Q&P: There’s a quote on the Richard Mille website characterizing you as “at the crossroads between classical ballet and modern dance.” Surely this is an apt description, but I think that this quote could also illustrate the artistry of the brand. Is this what drew you to it?

BM: No, I think the sophistication of the brand and the way that it seeks perfection [is what drew me to it] . . . it’s something that I try to achieve every day, in every performance. I take great joy in working with people who seek a kind of perfection when I look for collaborators. I think there’s a kind of excellence in what Richard does, so that was interesting to me for sure.

Benjamin Millepied wearing a Richard Mille RM 029

Q&P: Collaborators also in terms of dancers? When you’re putting on a production is that what you’re looking for as well? What draws you to particular dancers?

BM: You know, I think how clear their personality is through their way of moving and expressing themselves, their singularity is what draws me.

Q&P: I think it’s pretty safe to say that your choreography style is not classical. How would you describe it?

BM: Well, I think at the base I’m a classicist because there’s always very strong architecture and structure, and a lot of works. Like the first piece on tonight’s program [L.A. Dance Project at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in January 2019] is set to music, so it’s in a way classical even though the movements aren’t quite. Nowadays, I play with the way that I actually make the piece. But there’s still always classicism underneath all of it, you know, and in the architecture and in the structure always. I think there’s a richness to how space, rhythm, and timing are used.

Benjamin Millepied wearing his Richard Mille RM 029 (photo courtesy Richard Mille/Jaso)

Q&P: I can take that entire thing you just said and apply it to Richard Mille watches – that they don’t look like it, but underneath they’re classical.

So your choreography itself is a delicate dance between coming into the studio with your own ideas and allowing yourself to be inspired by what’s in front of you, with what the dancers are doing. How do you find the balance between these elements?

BM: It varies from piece to piece, but you’re lucky when you go in there and very inspired when you work with dancers you love, and, honestly, it makes all the difference in the world sometimes. When you’re really driven, and you walk in and there’s somebody really incredible. It’s what makes the art form so spontaneous and alive, the live element of having humans to work with; they’re not just paint brushes.

Q&P: But you are also involved in other types of art as well, aren’t you? You were telling me before about photography, making costumes, creating, but those are less alive things in comparison . . .

BM: Well, photography is an observation of the world, which is amazing and I love. Just spending time, but it’s also much lonelier, which is also very nice. Cinema is just a total art, so it brings all the things that I love: movement, narration, light, music.

Q&P: And how might you maybe incorporate the watch or something that has to do with this universe into what you do?

BM: Well, I think I’m an explorer of space and time to some extent.

Benjamin Millepied wearing a Richard Mille RM 029

Q&P: I’ve noticed a strong juxtaposition of your programs for the L.A. Dance Project. For example reviving historic pieces, such as those choreographed by Martha Graham, and placing them alongside modern pieces. What are your inspirations behind such contrasts?

BM: The really great works might be dated because of how they’re presented, but they’re undeniably timeless. And so I love to take something that’s old and reproduce it and show how timeless and how good it is and put it next to something new.

Sometimes it’s hard because you have masters like Martha Graham, who presented these small pieces for years, but they were incredible and you couldn’t put a time on them. I gave them contemporary simple costumes, you see them as pure choreography, it was really beautiful. So I love to do that. It’s also such an affirmable art form. And it celebrates all these choreographers that we used to celebrate but don’t anymore, and I always find that it’s great to bring their work back.

Q&P: That’s an interesting viewpoint.

BM: Yeah there are less and less revivals like that. But I’m starting to revive the work of a choreographer: Bella Lewitzky, a major choreographer from L.A. – but nobody really knows what the stuff looked like if they weren’t in L.A. in the 1970s or 1980s. There’s a crowd of people who were there in that moment and would go see the work and it meant something to them, but then the work just disappeared because she died and there was no internet, no film. So that’s really exciting.

Q&P: Is that easy to do in Los Angeles as opposed to France, where you’re from, for example?

BM: I think what’s beautiful with L.A. is that we’re kind of under the radar, you know, and that’s a good thing. If we were from here and we present a work, then we’d have to have all this press and so on; same with New York. In L.A. really there’s none of that. So you do your thing, you have your dance, and you’re just kind of doing your thing under the radar. It’s wonderful.

Q&P: Does L.A. have a big dance tradition?

BM: No, we’re the first company to have our own performance space in L.A.

Q&P: You’ve lived and worked in a number of places and you’ve got so much experience under your belt, you’ve been around the world and seen everything. Would you say your inspiration for the L.A. Dance Project is an accumulation of your personal experiences as a dancer and choreographer?

BM: Yeah some of it. It’s also a social understanding, too, of what art means to society – or should mean. I think the importance of creating a place where people gather and have a communal experience is interesting and enriching. There’s a lot more of a social understanding of our time. So, yes, as a dancer and as a choreographer I learned a bunch of things. But then you also really have to question yourself: what does it mean to have a dance company in a city? What are you creating and what’s the story here? So I think the implication of the place and the people means that the talent in that city has to be nurtured, it has to be diverse.

Q&P: And your inspiration for founding L.A. Dance Project?

BM: I just felt there was room for it. I thought there was room for a new company with a new proposal – we’re not like other companies, and that’s important.

Q&P: What is it like working with really famous – practically legendary – dancers like Mikhail Baryshnikov?

BM: It’s good, I mean I’ve had good experiences with these people and like everybody that I’ve worked with.

Benjamin Millepied wearing a Richard Mille RM 029

Q&P: How would these sorts of experiences influence your work as a whole right now?

BM: Well, they do especially if you work with people in other art forms, you kind of you understand their process and their field and their place in their field and the history of it. Usually it’s always an interesting parallel or you learn from working with collaborators in other fields.

Q&P: That’s a good thought. Have you worked with other renowned artists in other fields?

BM: Yeah, like Christopher Wool and Barbara Kruger.

Q&P: I’m a big fan of the film Black Swan, where you were a choreographer and where you met your wife, Natalie Portman. I’m curious how accurate you think the portrayal of a professional ballerina was in the film?

BM: Well, ballerinas don’t turn into swans (laughs). But of course, there are aspects that are pretty accurate in the life of a company. But I’ve only seen the movie once, so it’s pretty hard for me to say.

For more information, please visit richardmille.com/en/collections/rm-029 and/or benjaminmillepied.com.

Quick Facts Richard Mille RM 029

Case: 48 x 39.7 mm, titanium

Movement: automatic Caliber RMAS7, fast rotating spring barrel and carbon nanofiber base plate and ARCAP

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; large date

Retail price: $80,000 (titanium), $97,000 (red gold)

Year of introduction: 2011

You may also enjoy:

Richard Mille RM 53-01 Pablo Mac Donough: A Timepiece Warrior Persians Would Have Appreciated

Alexander Zverev’s Ultra-Light Richard Mille RM 67-02 Is Serving Aces

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!