The How And Why Of Patents, Including The World’s Most Famous Watchmaking Patent Granted For Abraham-Louis Breguet’s Tourbillon

Patented inventions are present in every aspect of human life. Electric lighting glows in our rooms due to patents held by Thomas Edison and Joseph Swan; plastic is omnipresent thanks to patents registered by Leo Baekeland; and even ballpoint pens would not be on every desk if Laszlo Biro hadn’t patented them.

A patent is not something you are going to run across every day. Anyone working in a technical field may know a little about the process, which basically grants exclusive rights for an invention, a product, or a process that has generally made a new way of doing something available or perhaps offers a new technical solution to a problem. The patent, which is usually granted for a period of 20 years, provides the owner with protection from others copying and selling the invention.

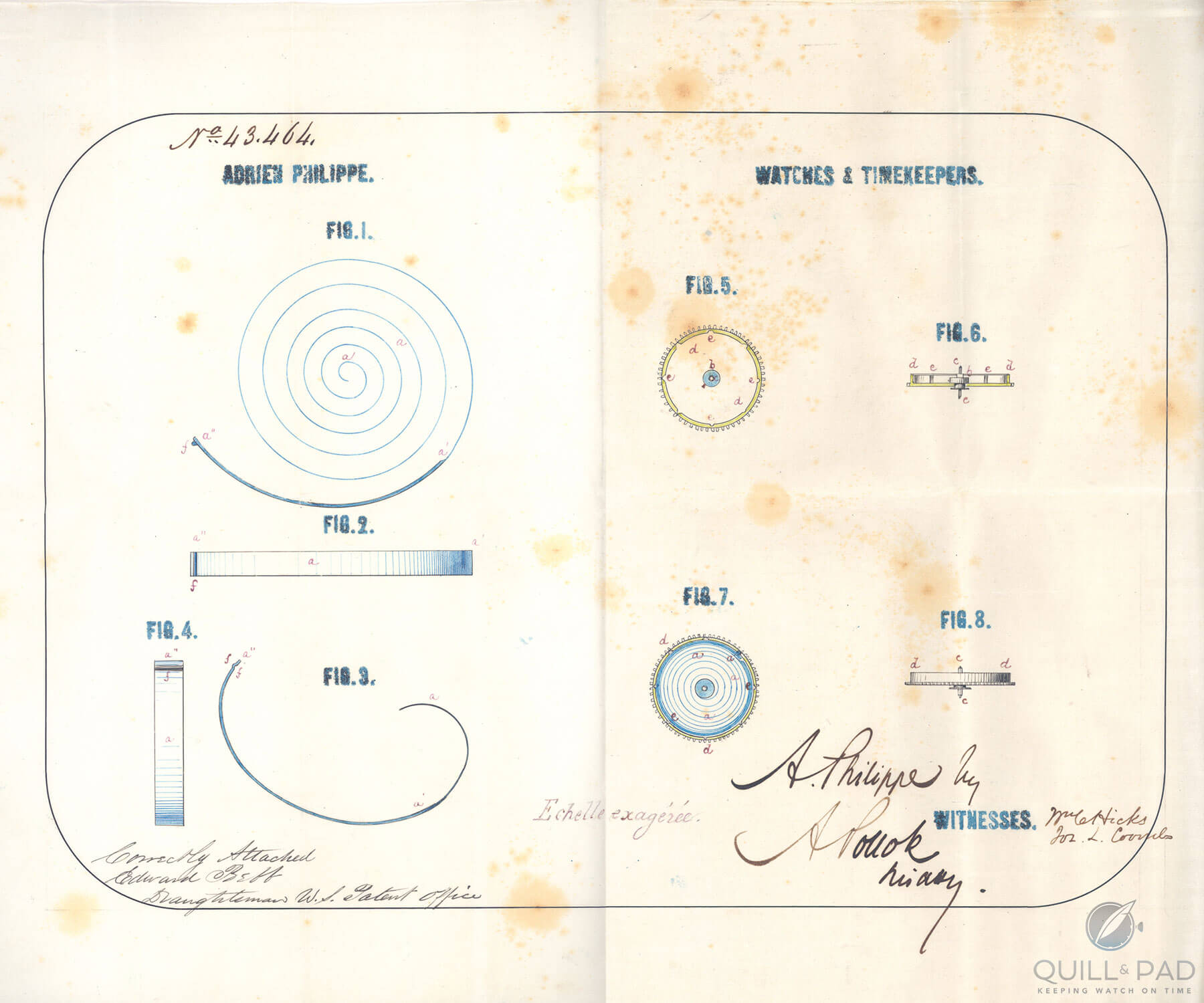

Adrien Philippe’s patent from 1863 for a slipping spring, which ensures the mainspring isn’t damaged by overwinding

The first step toward getting a patent is to file an application, which will usually contain the name of the invention, an indication of its technical field, its background, and a description of the invention. The latter may be accompanied by visual materials, and watch industry-related patents almost always contain horological drawings and plans.

The field of horology is currently patenting more inventions than ever before – or at least so it seems – but are all these official certificates justified?

Worldwide patents

Patents are granted by national and regional patent offices such as the European Patent Office. The Patent Cooperation Treaty has the same effect as national applications filed in designated countries but allows the owner to only have to file one international patent application.

At present, no world or international patents exist according to the World Intellectual Property Organization, a specialized agency belonging to the United Nations. Patents are granted and enforced in each separate country. However, the European Patent Office and the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization both grant patents in the member states of their respective regions.

Watch industry CEOs have told me that worldwide patents are not as important to a watch company as the consumer might think, with the most important registered in Switzerland and the European Union, where the cradle of the watch industry is located. Many also register patents in the United States.

The most famous horological patent: Abraham-Louis Breguet’s tourbillon

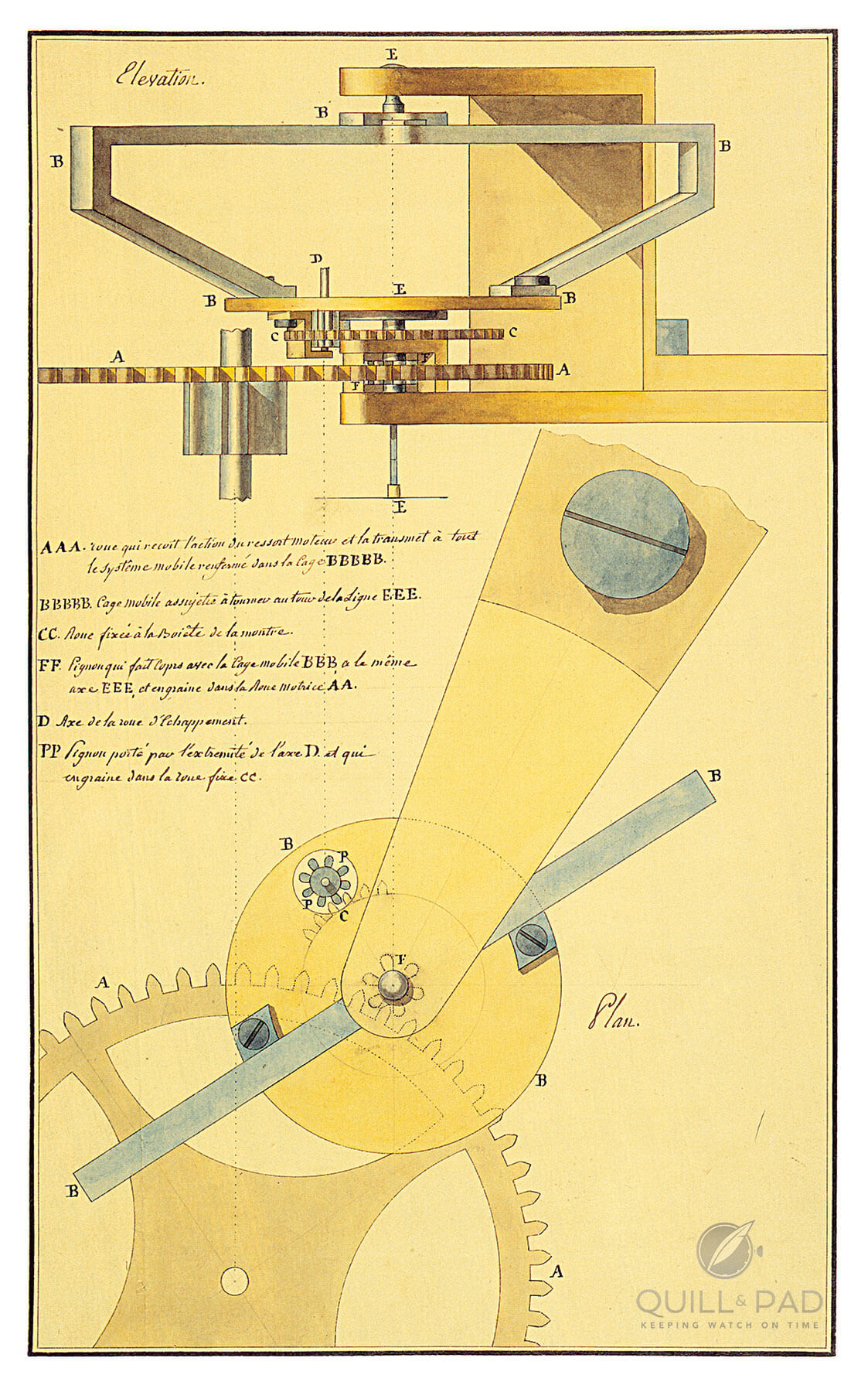

The most famous patent in modern wristwatch history – the stuff of legends, actually – is Abraham-Louis Breguet’s April 14, 1801 patent on his tourbillon, granted to him by France’s ministry of the interior.

The patent for Breguet’s now 200 -year-old tourbillon has long expired, so his invention is free for all to use. Modern-day Montres Breguet SA in L’Abbaye, Switzerland, is perhaps the most justified in using tourbillons – and has filed a number of other patents based upon it, such as U.S. patent number 7350966, describing a “watch including at least two regulating systems.”

Abraham-Louis Breguet’s 1801 patent for the tourbillon

Watch aficionados are likely to understand that Breguet’s phenomenal Double Tourbillon Reference 5347 is the timepiece described in its technical text.

This patent protects the invention of the mechanical movement comprising at least two “regulating systems,” better known as escapements. The movement is described as containing a gear train that conveys energy from the spring barrel to the escapement, while a differential gear connects each gear train’s barrel so that the rate of the two subgroups is averaged out. The two regulators are attached to a common rotating support, while the tourbillons make an orbital movement around the center of the dial.

Breguet Double Tourbillon Reference 5347

Breguet’s original tourbillon patent has long expired, but Christian Lattmann, former vice president of products at Breguet and now CEO of sister company Jaquet Droz, once explained to me why patenting remains so essential to the Swatch Group brands.

The reasoning is simple: nobody disputes the patent that Breguet had for the tourbillon device. Breguet is recognized by all as the inventor of the tourbillon. On the other hand, according to Lattmann, Breguet was also the first watchmaker to use winding crowns instead of keys for winding watches. However, Breguet did not patent this device.

Today, Breguet cannot claim to have invented winding crowns because another brand deposited a patent on this. So now, the R&D department requests patents on all new devices to ensure legitimacy on new inventions.

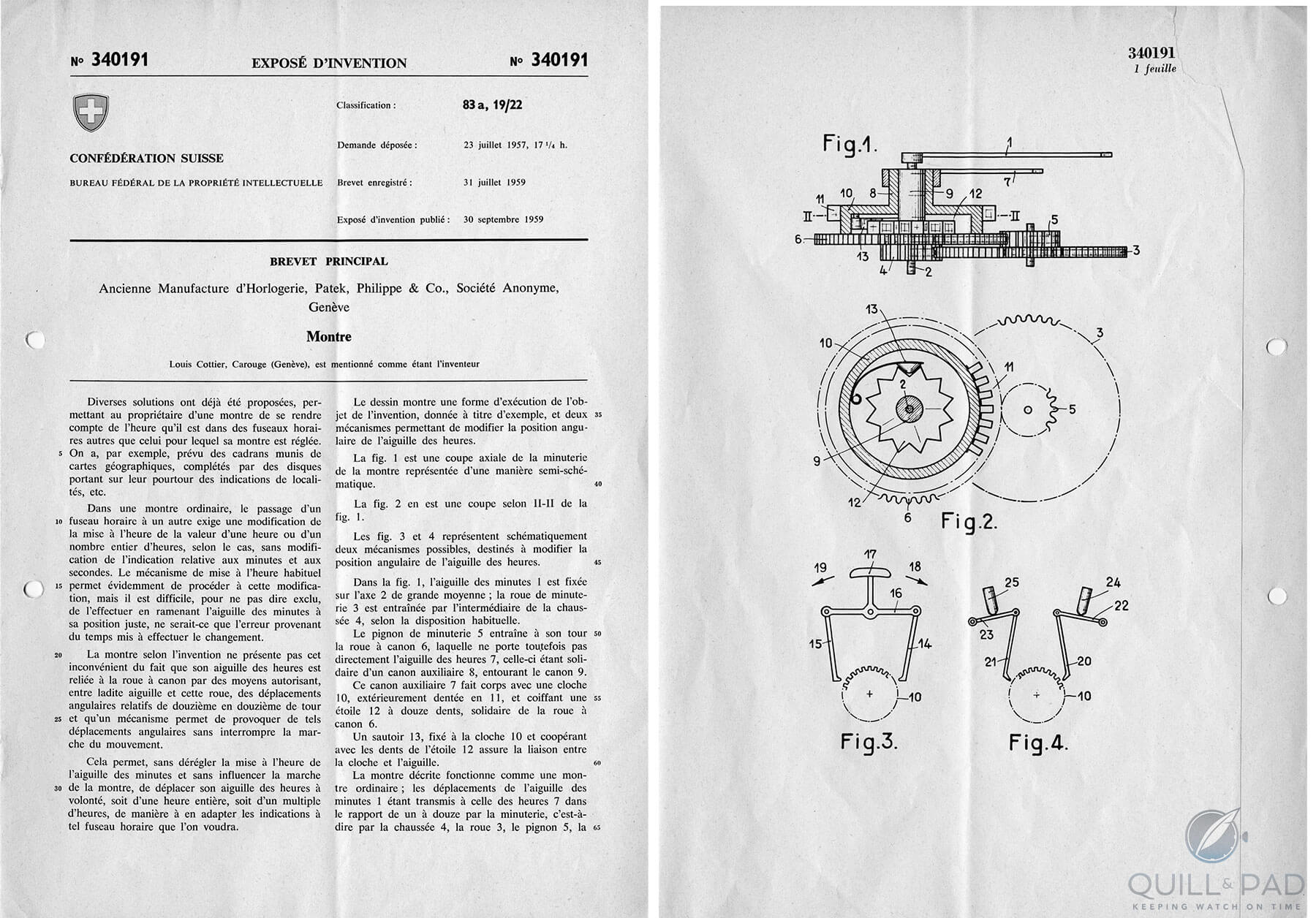

Patek Philipp patent 340191 for a universal time mechanism

Earning respect with patents

As we saw in Tim Mosso’s comprehensive four-part history of Rolex movements, patenting is an almost automated process for big brands like “the crown” today.

Small brands always have to prove themselves first, needing to earn respect, an important factor in their continued success. Something that helps is the fact that inventions for technically challenging or innovative mechanisms or processes can be patented.

Armin Strom Masterpiece 1 Dual Time Resonance

One small brand with an outsized patent portfolio is Armin Strom, which has registered its unique Resonance Clutch Spring with the European Patent Office. The spring, an almost butterfly-shaped component establishing resonance, was calculated, simulated, prototyped, and shaped to scientific perfection within the four walls of Armin Strom’s Biel-based manufacture.

And that important element in the Mirrored Force line was well worth protecting.

Another is independent watchmaker François-Paul Journe, who fastidiously patents his inventions. The movement of his Sonnerie Souveraine from 2006 alone had ten new registered patents.

U.S. patent number 6948845, published in 2005, was used in the Geneva-based watchmaker’s Centigraphe. The object of the “storage device” registered was to eliminate problems involved in conveying energy from the spring barrel to the timepiece’s escapement by improving the balance wheel’s isochronism, giving it an even rate and using only a small number of components.

Journe primarily patents his innovations to make sure they are not copied. It is his desire to protect his ideals of haute horlogerie and his hard work researching at the bench. He is adamant about not having his inventions used unlawfully.

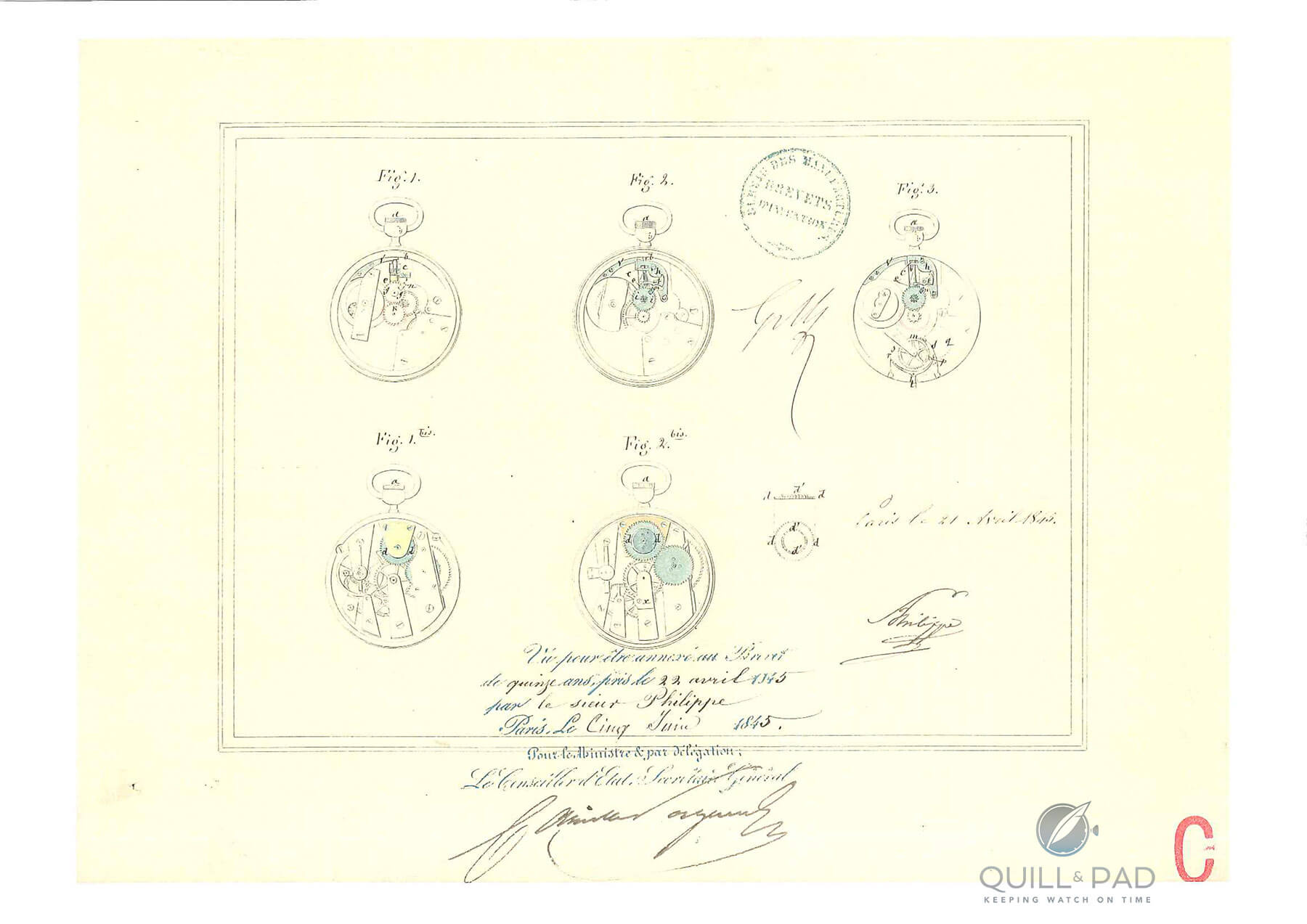

Patek Philippe patent 1317 for th invention of a new winding system for the pendant watch

Too many patents?

Today the patent has become a watch brands’s “proof” that it is continuously innovating. Whether the current fill of patenting is justified or not is something that consumers must decide for themselves.

In the end, I feel that a certain percentage of patents are registered to gain attention, impress others, and possibly create a little hype, while others are certainly justified as elements worth protecting.

It is important for a manufacturer of luxury mechanics to put its technical prowess on display, and a patent emphasizes that.

However, do remember that a patent can also be a marketing instrument – especially if the element loudly and proudly touted as patented does no more than make one wonder if it’s really a technical marvel or indeed a marketing tool.

You may also enjoy:

A Synchronistic Technical Tour De Force: Armin Strom’s Mirrored Force Resonance

The Sonnerie Souveraine By F.P. Journe: A Legend In Its Own Time

The Golden Age Of Rolex Movements Part I: Sowing The Seeds Of Greatness

The Golden Age Of Rolex Movements Part III: Branding vs. Breakthroughs In Recent Years

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!