by Martin Green

Adding a few diamonds to a watch: how hard can that be?

As it turns out, stone setting is a lot more difficult than many appreciate. Diamond-setting watches requires the expertise and craftsmanship of about half a dozen highly skilled craftsmen, each a master of their craft.

Setting a watch case with diamonds at Chopard

Personal preferences aside, a diamond-set watch is a work of art, especially when we move away from the simple diamond hour marker or gem-set bezels and into the territory of more elaborately set pieces.

Let’s start with . . . diamonds!

While diamonds are mainly known for being expensive and sparkly (“fire” and “scintillation” being the more professional terms) there is so much more to them.

The Backes & Strauss signature ‘jewel in the crown’ is designed to look like the pavilion (lower portion) of a diamond

Even before humankind was able to cut and polish diamonds, they were already revered items: not surprisingly, as they constitute the hardest natural material in the world.

As if that is not cool enough, it takes the mass of the entire planet to create a diamond, about 160 kilometers under the earth’s crust, with its extreme pressure and high temperatures. There carbon elements form an isometric structure, which means that all the carbon atoms are connected in the same way in all directions.

A diamond is nearly pure carbon, typically consisting of 99.95 percent carbon atoms and 0.05 percent of what are called trace elements. While these trace elements don’t make up the essential chemistry of the diamond, they can influence its color for example: the hues of yellow, blue, and pink diamonds are influenced by the trace elements in them; in general diamonds are colorless.

A variety of diamond sizes at Chopard

Many are unaware that the majority of diamonds are more than one billion years old. After they were formed deep in the earth’s crust, they slowly pushed up from the core of the earth to depths more accessible to humans.

That still doesn’t make diamond mining a walk in the park and it requires significant cost and effort. The yield of each diamond mine is different, but in general to find one carat’s worth of diamonds – a mere 0.2 grams – 200 kilograms of rock need to be mined and processed.

If that is not dazzling enough, think about the fact that only a very small percentage of these diamonds is of a quality high enough to be used in watches and other jewelry.

There are four Cs, but only three matter for watches

While rare and precious, a diamond that is uncut and unpolished does not have the same appeal as one that is.

With gems in general, and diamonds in particular, what’s important in determining their value are what’s called the four Cs: color, clarity, cut, and carat (weight).

When it comes to watches, though, that last one is of almost of no concern. Unlike, for example, a ring, a watch set with diamonds becomes a piece of art due to how the diamonds are integrated into the overall design of the watch, not how large they are.

The value of a diamond-set watch is more based on the number of diamonds, and therefore the total carat weight, rather than the weight of an individual stone.

The GyroGraff Drive displays Graff’s uniquely cut diamonds on its bezel

With the cut, we don’t only mean the proportions, symmetry, and polish of the stone, but also its shape. On watches brilliant-cut and baguette-cut gems are the most popular, but many watches, especially those with more elaborate settings, feature unique-cut shapes, which add a whole new dimension to the complexity of the watch. The watches of Graff are a good example of the latter.

Designing a diamond watch

This process starts off with the design of the watch. When an artistic design has been created, different crafts come together to turn it into reality.

Especially if the diamond-set watch is based on an existing model, designers often prefer that the shape of this design is still recognizable.

If they want to fully set the watch with baguette–cut diamonds, chances are that the vast majority of the diamonds used on this watch are not cut in the baguette shape. To follow the contours of the design, the cut of many diamonds are adapted to their places on the watch.

Designing a gem-set watch at Bunter, Switzerland

Technically this is quite difficult because it means that the diamond cutter needs to create shapes specifically for the watch. The criteria here is not only that the stone will perfectly fit the place designated for it, but also that it still shows off the unique beauty diamonds are so renowned for.

Adding to the complexity is also that watches are three-dimensional objects, meaning that in some cases it also needs to cover a difference in height, for example, near the edge of the watch.

How challenging must it have been to cut and polish the 118.78 ct Graff Venus diamond? Granted, it was not conceived for use in a watch, but still . . .

The diamond cutters are not the only ones facing challenges; the diamond setters do as well. It is up to them to incorporate the cut and polished diamonds into the watch.

There are several ways to do this, but the most popular, especially with fully set watches, is what is known as invisible setting. This means that you can’t actually see how the stones are secured to the metal, and this is indeed as difficult to accomplish as it sounds.

In either case, to secure the diamonds the diamond setter needs space/volume and does so by drilling and carving into the case.

While this is fairly easy – as these things go – with a diamond-set bezel or even lugs, it is quite different to set the whole case with diamonds. Often the watch must be redesigned in a CAD program, which allows the designer to map out the different diamonds and cuts needed in addition to how much of the case needs to be carved away to accommodate them.

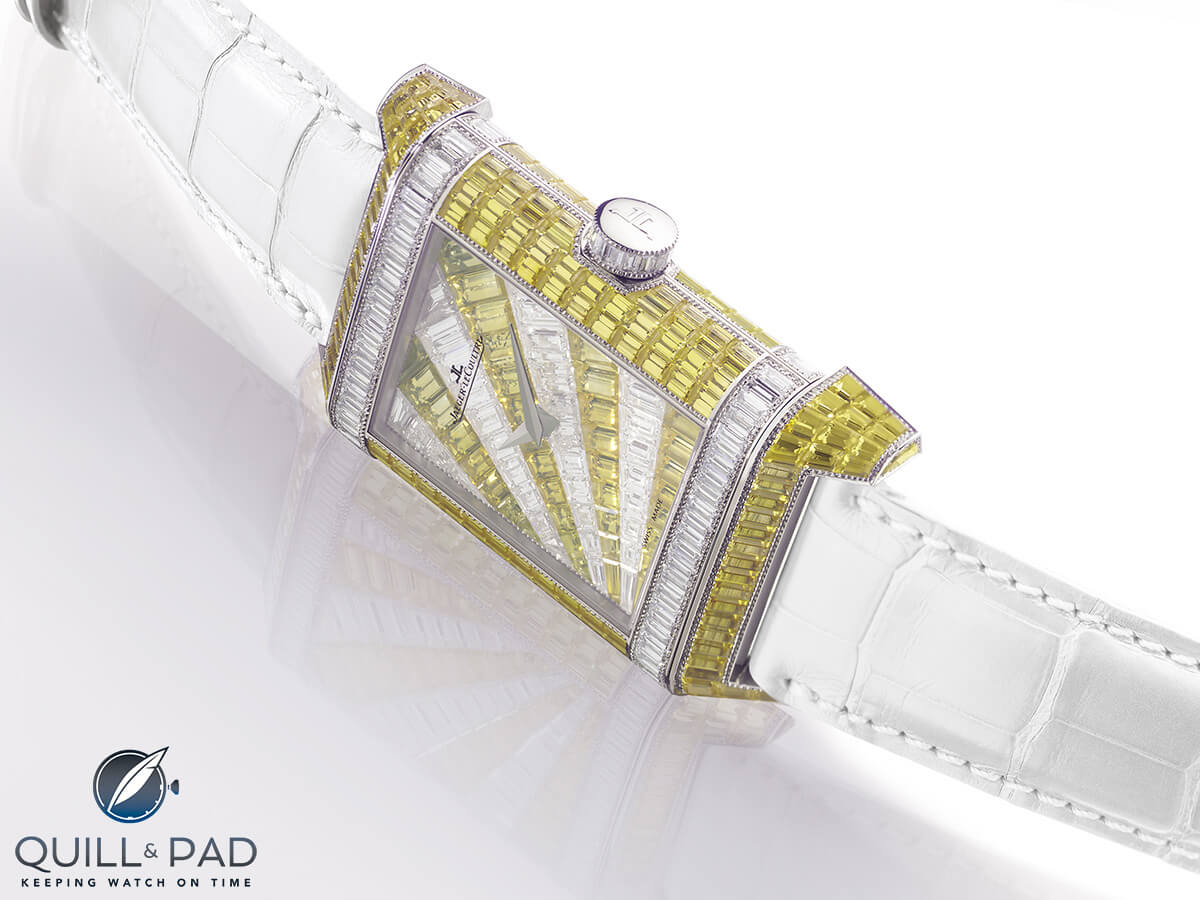

A Jaeger-LeCoultre Grande Reverso with the impressive rock setting invented by master gem setter Alan Kirchhof, which sees baguette-cut diamonds turned upside down; molten gold between the stones secures them to the case

Taking metal from the case means that its integrity is also weakened, and by planning ahead the correct amount of metal can be removed. This also helps to prevent a common problem with aftermarket-set diamond watches: punctured cases. This means that the integrity of the watch is still intact, but by drilling too deeply, a tiny opening was created in which moisture and dust can enter the watch case, wreaking havoc on the movement and dial.

Raising the stakes

Just like watchmakers, clever diamond cutters and setters also enjoy a good challenge. As if setting a watch with diamonds isn’t complicated enough, they raise the stakes by putting a pavé setting on an ultra-thin watch.

Piaget’s Altiplano 38 mm 900D, the world’s thinnest high jewelry watch

The challenge here is of course that these watches are so thin that only so much metal to place the diamonds can be cut away. Of course, the cut of the diamonds used also becomes rather shallow, at which point they show off less of their fire and scintillation.

This provides diamond cutters and setters with a whole new dimension to showcase the considerable skill that they need to have to even attempt a project like this.

If that is not enough, brands like Piaget and Graff also like to fit their watches with skeletonized movements whose bridges are set with diamonds.

A proper skeletonized movement sees as much of the bridges and the main plate cut away as possible while still maintaining the rigidity to ensure its timekeeping capabilities. Cutting away even more to accommodate the diamonds is like walking a haute horlogerie high wire – and further proof that diamond-set watches are a complication of their own.

* This article was first published on April 26, 2018.

You might also enjoy:

Can A Man Wear A 60.66-Carat Diamond? The Roland Iten R60 Diablo Belt Buckle Says Yes

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

hi

It’s regrettable that this author didn’t mention the fact that tons of diamonds are dumped in the ocean every year and many of the best are stashed in vaults by manipulative diamond companies to increase profit from inferior stones. Diamonds are a con. Nothing more.

I really like the Jewel in the Crown of Backes & Strauss watches. Diamonds on just about anything will make it look nicer but looking at their collections, it is refreshing to see a watchmaker integrate diamonds into the structural design of the piece rather than just decorating the case with them. This is visible in collections like the Royal Piccadilly Princesses, where the stones become part of the strap and case and are far less bulky than you expect with such a high number of diamonds, which is an all too often setback in trying to find the right ladies’ watch.