Discovery, Firsts, And The Louis Moinet Compteur De Tierces

I do hereby claim this article in the name of Quillandpadia and its emperor and empress, Ian the Clever and Elizabeth the Wise!

I can do that, you know, because I was the first one to write those words. That’s just one of the perks of being first: the ability to claim things, to have naming rights, and profiting from your endeavors.

There are many firsts in the history of the world that prove this time and again. There are examples of products, concepts, technologies, scientific discoveries, and most especially exploring the world.

But first take Q-Tips, Kleenex, Wite-Out, Super Glue, Velcro, Chapstick, Jet Skis, Frisbees, or Band-Aids for example. All of these were first examples of, or at least the first most widely known versions, products many people use every day. And because of that we know them by these names, rather than what the products are technically called, such as cotton swabs (which you should never put in your ear canal).

The inventing companies took, or landed by default, naming rights and so were also able to cash in mainly due to being first out of the gate.

There are scientific discoveries that happen all the time as well, like finding a new element in the remains of a particle collider experiment. The scientists who discover them get to name them, which is why we have so many elements named after scientists, research institutions, or places like Californium and Fermium. Middle Eastern and Arabic culture largely invented the discipline Algebra, which is why it isn’t Latin- or Greek-sounding like Trigonometry or Calculus.

Some of the longest-lasting firsts in terms of remembrance are the explorers of the world. The Wright brothers made the first motored flight and Charles Lindbergh the first transatlantic flight.

Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay were the first to successfully ascend Mount Everest . . . who can remember the second?

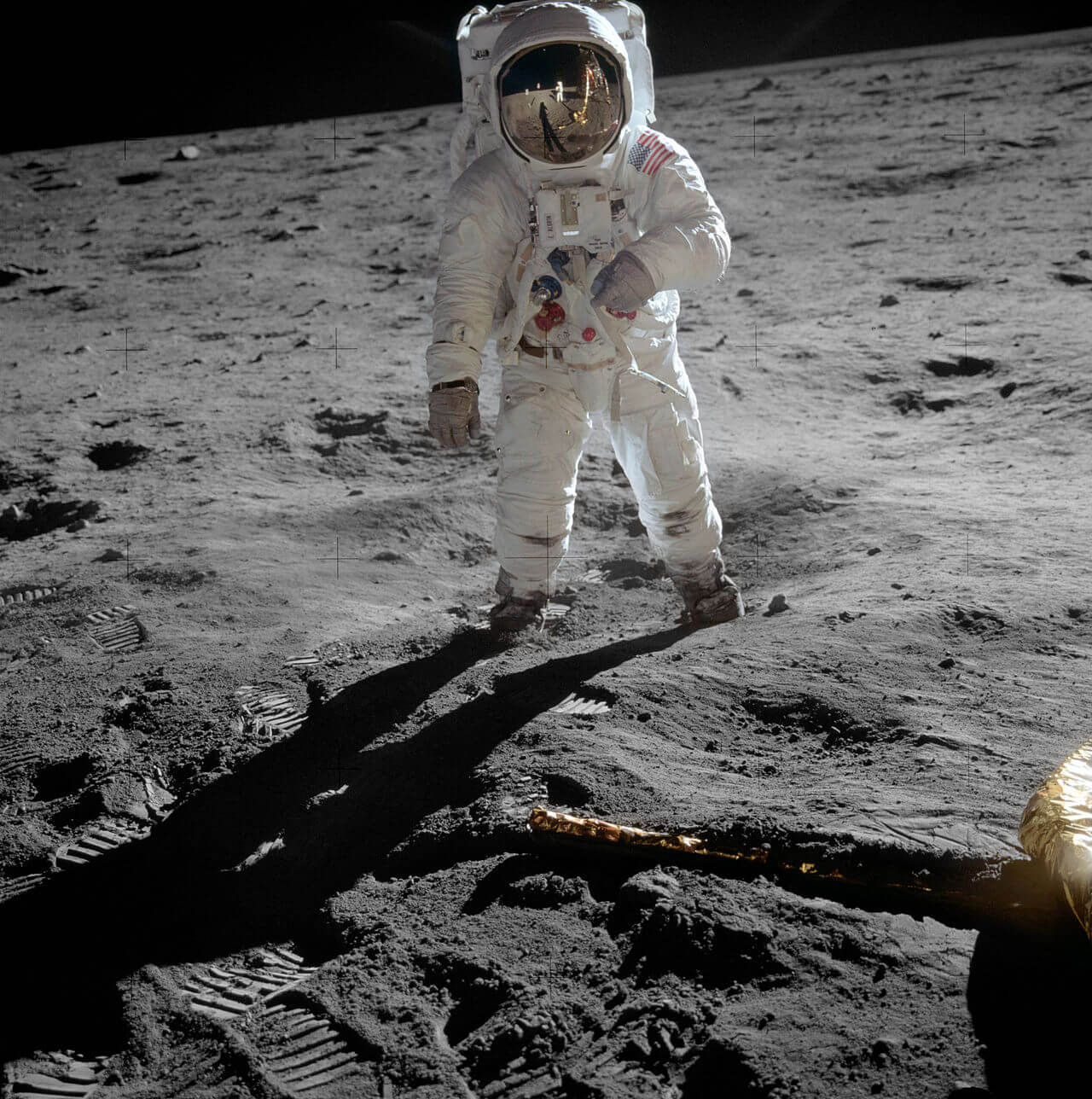

Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were the first humans on the moon; Ferdinand Magellan was the leader of the first voyage to circumnavigate the world; and Christopher Columbus was the first captain to take a wrong turn and wipe out an entire indigenous people.

Being first counts

But I digress from my point. Firsts are remembered and revered. So much so that for a while there was an internet fad to be the first person to comment (where comments were possible) by commenting, most appropriately, with “FIRST!!” Happily, that trend has died away, but our culture still respects the concept of firsts, and as such, being able to claim them can be very advantageous not only for pride, but also for the bottom line.

Many companies even bank their marketing strategies on being first, which has, historically, proven to be a reasonably sound risk.

But what happens when a discovery is made that takes your first and makes it…second!? What do you do?

Either you cross your fingers and hope the discovery is a mistake, or you try to re-categorize your first by a new aspect so that it retains the title of being first, if only for another reason.

But what if you are the benefactor to that discovery, and it takes your brand to new heights as the new first something-or-other? Then it is oh-happy-day!

In science, this happens rather regularly as new evidence changes the landscape of theories and the one regarded as being more accurate.

In history it happens with even more regularity; as research methods improve, the ability to search and compile documents increases, and the capacity to cross reference thousands of pieces of information while looking for patterns expands with technology.

So why is it that sometimes history surprises us? Especially when we think, even for a very long time, that there isn’t anything more to know? After a period of facts being presented as facts, we stop asking questions until something smacks us in the face as being so incredibly obvious it is a surprise nobody had noticed it before.

This happened in 2013 when word of an horological discovery was released to the watch community. People were dubious, surprised, and, rightly, very excited.

This news was of a first, one that redefines the progression of timing technology. The discovery was of the very first chronograph ever made, seven years before the previously known earliest chronograph and decades before anything remotely similar would be constructed.

It was the Louis Moinet compteur de tierces, or “thirds timer,” and I, along with many others, was very, very excited.

The compteur de tierces is one of the most remarkable finds in horological history in an extremely long time. It’s remarkable for a few reasons, and awesome for a few more, so let’s get to it.

Jean-Marie Schaller, CEO and creative director of the modern Louis Moinet band, proudly holding the Compteur de Tierces

It was first, period

It was the very first chronograph ever made. Louis Moinet (1768-1853) was a friend of Abraham-Louis Breguet and often worked with Breguet. He made himself the compteur de tierces for timing astronomical observations and transits and completed it in 1816. That was a full seven years before the next one to be made, and it was almost another decade before the next chronograph appeared.

Note: today we would call these stop watches as they only timed interval. Modern chronographs usually display the time as well as time intervals.

According to a letter Louis Moinet wrote in 1823, “I came to Paris in 1815 with the sole purpose of devising and making a compteur de tierces. The difficult and seldom attempted realization of this instrument of a new construction, has achieved my purpose most satisfactorily.”

This isn’t a story of two individuals developing something in tandem and one finishing a couple months earlier (which is the case with many inventions, including the printing press and, famously, the automatic chronograph), but instead of someone clearly building something long before anyone else ever had the idea… or at least the ability to.

This would be akin to a company three years from now announcing it had made a digital tablet device that can do everything your computer can do and it also features a touch screen and great design. People would politely reply, “Thanks, but Apple already made one seven years ago. Nice try though!”

However, two hundred years ago people didn’t have instant access to global information, and the compteur de tierces wasn’t a mass-produced item but a one-off piece of engineering art. So it is very reasonable to understand that it wasn’t known for this long.

It is even more impressive to think that it was discovered and verified after so much time of believing that Nicolas Rieussec had invented the chronograph in 1822.

It is a true chronograph in every modern sense of the word.

The compteur de tierces isn’t just special because it was first, it’s special because it was engineered like a chronograph and as such has features that would slowly be rolled out over the following decades. The list is as follows:

- The dial layout is comparable to almost every modern chronograph and would be considered an almost standard 3-6-9 layout, simply with the 6 and 9 squished a bit toward the 12.

- The layout splits time intervals into different sizes with the center being sixty parts of a second, the two top subdials being elapsed seconds and minutes, and the bottom subdial showing elapsed hours for the ability to time up to 24 hours.

- It contains a reset function, allowing for more accurate and repeatable measurements.

The Louis Moinet Compteur de Tierces has two chronograph pushers: one to start/stop the watch, the second to reset the central 1/60th second hand to zero; a second operation is required to reset the other counters

- The start, stop, and reset functions are controlled by two buttons on the top of the case.

- Compared to the Rieussec invention, which could mark off individual seconds, the compteur de tierces could measure down to 1/60th of a second thanks to a 30 Hz escapement. 30 Hz or 216/000 V/H, that’s not a typo, most modern balances beat at 4 Hz, a few fast balances beat at 5 Hz and there has even been the odd one or two at 10 Hz.

- 30-hour power reserve and power reserve indicator. Despite the ultra-fast balance frequency, it still had an incredible 30-hour power reserve AND you could wind it while it ran for extra-long timing intervals.

Basically, the compteur de tierces displays most aspects of what chronographs would become long before anyone else made them for production.

It can measure time intervals to 1/60th of a second

This is a big deal, and not just because it was accurate. It was revolutionary. Being able to time an event in an interval smaller than anyone else meant you were that much more accurate, so being six times more accurate than even the best contemporaries was ridiculously huge. While only the best of your competitors were timing down to 1/10th of a second, you were timing their timing to see who was running fast or slow because, well, just because you could.

This doesn’t even touch on the technical ability that it took to achieve this feat. A simple 2.5 Hz escapement is already an exercise in precision tolerances and fine adjustment. Escapement teeth need to slip and catch at just the right moment and exactly the right angles to allow for smooth action and proper engagement.

Increase the frequency up to the now somewhat standard 4 Hz and lubrication and precision need to increase. But if you jump all the way up to 30 Hz or 60 beats per second, the forces and the tolerances would need to be absolutely, positively spot on.

Finally, the compteur de tierces is a work of art.

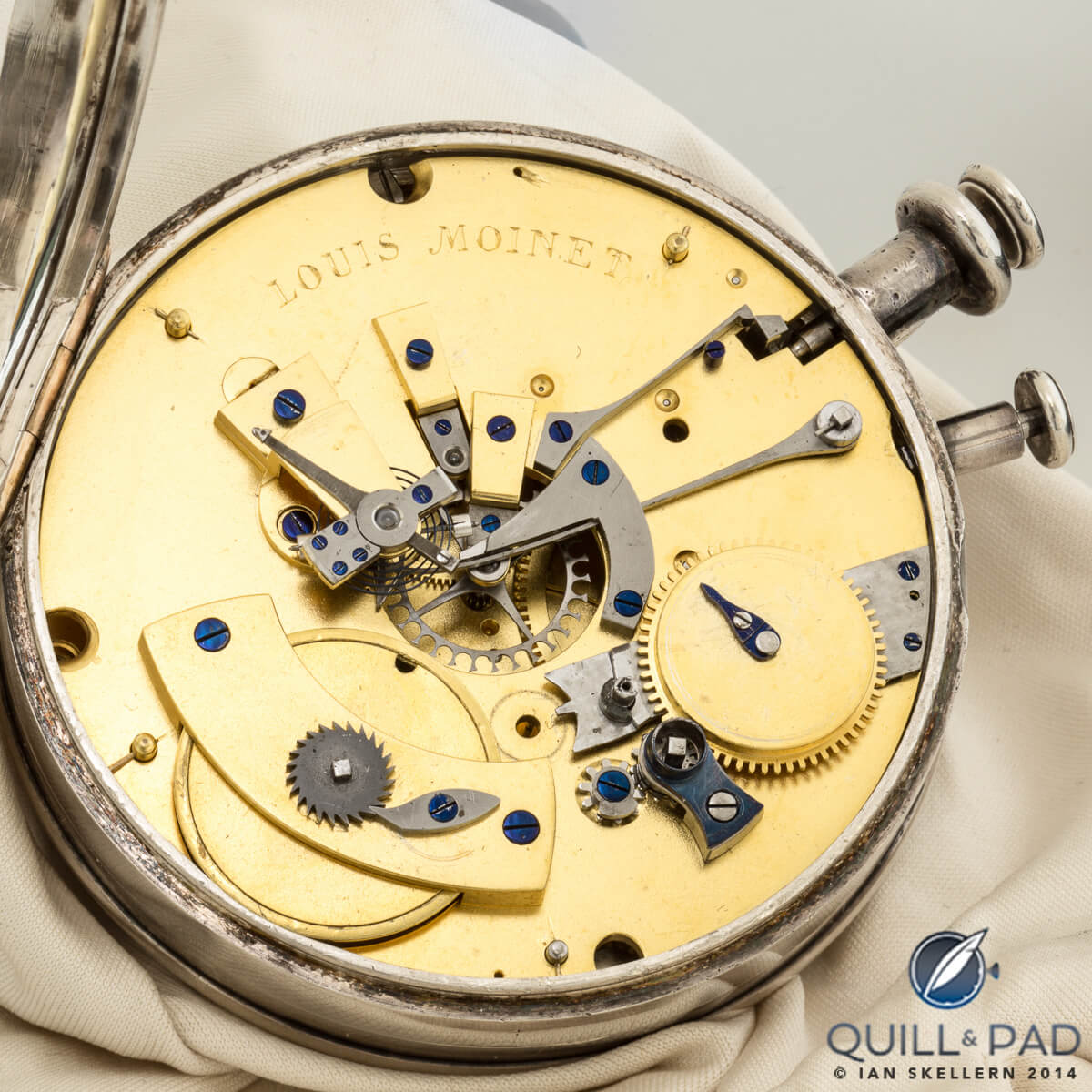

The case design and dial layout are understated, clean, and beautiful. The proportions of the dial don’t leave me wanting; instead it seems almost organic in its balanced shapes. But the real star of the show is the movement itself.

It is, if I do say so, ahead of its time in that it looks like it was created at a much later date with how clean and pristine the movement is. The bridges are simple and straightforward, the finishing very restrained but high-quality.

If I didn’t know any better, I would say it could have clearly been an inspiration for a modern Greubel Forsey piece like the Technique. It speaks very strongly of components built to display the precision engineering without needing to embellish or decorate.

The plates and bridges are gilded, probably for more practical reasons than decorative since, if done properly, gilding can be excellent corrosion protection.

When I look at the compteur de tierces movement, I feel that I am seeing something designed by a man that wanted to build an extremely functional and expertly made machine, and the beauty inherent in the construction is what should be focused on.

The Louis Moinet compteur de tierces is most definitely one of my favorite vintage pieces of all time because of every aspect behind it and all of the horological history that followed. It broke down barriers that others wouldn’t even come close to for years, and it did so humbly and without bravado.

Instead, it did its job perfectly (still does, too) without causing too much of a fuss. Most remarkable is how it laid low for almost 200 years before sauntering back into our lives with a simple, “What’s up guys? Oh, me? Yeah I could do all that stuff, no big deal, anybody wanna grab some shawarma?”

Mmmm, now I’m hungry.

The Louis Moinet Compteur de Tierces has four displays: a long central hand rotating once per second, and three subdials indicating elapsed seconds, minutes, and hours

For more information on the discovery of this amazing timepiece, please read History Rebooted: The Chronograph’s Inventor Is . . . Louis Moinet! and visit www.louismoinet.com/louismoinet-chronograph.

* This article was first published on August 25, 2014 at Discovery, Firsts, And The Louis Moinet Compteur De Tierces.

You may also enjoy:

Memoris By Louis Moinet: Paying Homage To Historical Chronographic Ingenuity

Louis Moinet Ultravox Hour Striker: Chiming Horology’s Mechanical Past

Louis Moinet Spacewalker: Spectacularly Highlighting First Human Spacewalk By Alexey Leonov

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

What a wonderful piece of engineering, and a great history lesson to boot! I also enjoyed your dig at the over-celebrated Columbus 😉

Also I must note that Fermium was named after famed physicist Enrico Fermi, not a place as far as I know.