Early American historian and Harvard professor Laurel Thatcher Ulrich titled her 2008 book Well-Behaved Women Seldom Make History.

Ulrich, of course, was mainly referring to American women found in literature. But she would probably be very interested to know about three famous Swiss and French brands whose very first wristwatches were made for – and in a way by – women.

And not all of these women would have necessarily been deemed “well-behaved” in their day.

Caroline Murat and Breguet

Caroline Murat was the sister of Napoleon Bonaparte and the queen of Naples. The Bonapartes were relatively ambitious as well as proud of displaying their status and wealth.

Thus, Caroline often engaged in royal intrigue. According to a document reprinted by the Napoleonic Historical Society of America, she also possessed a pure, pale complexion and felt that wearing jewels was disadvantageous to her skin.

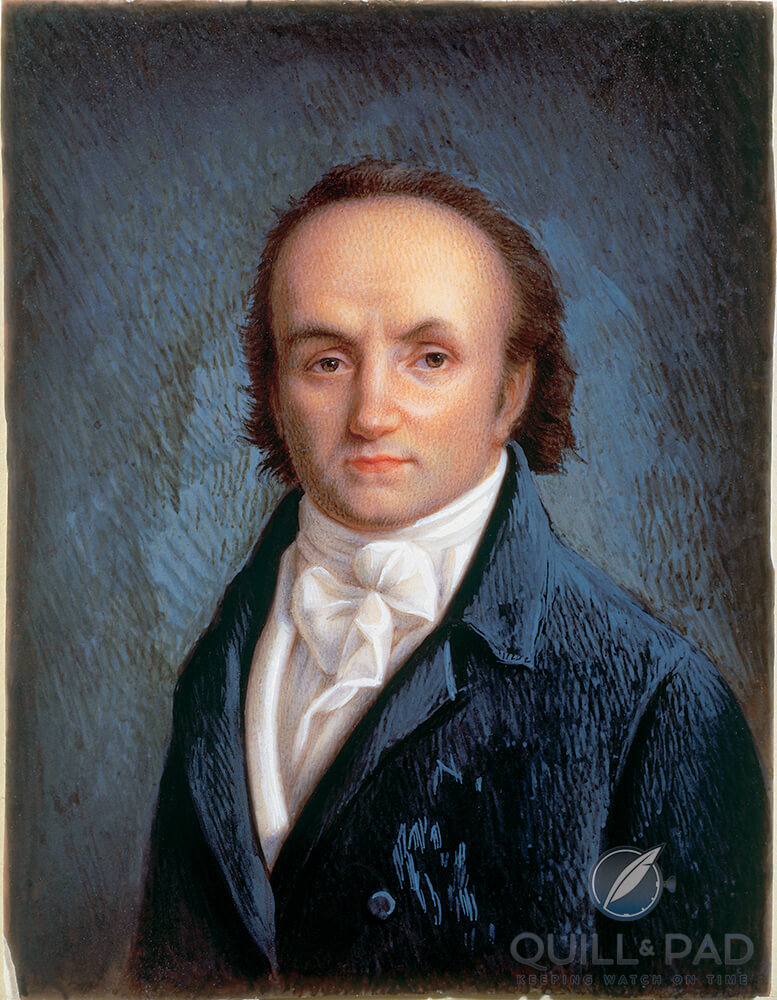

I conclude that perhaps this is why she became so enamored of the products created by the most prominent watchmaker of the time, Abraham-Louis Breguet, who lived in Paris. Breguet was the preferred horologist of Europe’s rich, famous and royal.

At the time, he generally made pocket watches and carriage clocks, sumptuously complicated and lavishly finished. Though these objects were as a rule almost always sold to men, there are always exceptions to every rule.

The world’s first wristwatch

According to Emmanuel Breguet, historian and descendant of the man considered watchmaking’s greatest personality, Caroline Murat bought her first Breguet in 1805, when she was just 23 years old. By 1814 Murat had bought 34 timepieces from Breguet, including one in 1812 that would become Breguet’s – and the world’s – first wristwatch.

Co-designed by the exacting queen, Breguet’s timepiece number 2639 was an “oblong repeater for bracelet.” The watch was delivered two-and-a-half years after it was commissioned, and sold for the princely sum of 4,800 French francs (as an aside, this was 200 francs less than his original estimate to her when she ordered it).

In addition to the unusual case shape, one jewelry element aided in distinguishing it from every other timepiece of the era: a wristlet made of hair woven with gold thread.

While the key-wound quarter-repeating movement, which also contained a mechanical thermometer, was typical of Breguet’s style, the oval case was decidedly not. Pocket watches were almost always round, and it was only a decade later that manufacturers frequently made “shaped” cases for wristwatches to signify that they were purpose-built for the wrist rather than being pocket watches with soldered lugs.

A modern interpretation

In 2002, the modern Breguet brand introduced the Reine de Naples line in tribute to this exceptional historical piece, which was last seen in 1855 when it returned to Breguet’s workshop for repair.

The modern line is characterized by an elegant oval case that is still unusually shaped even by today’s standards. It also displays technical movement prowess and playful bracelets like that of the queen’s original timepiece, descriptions of which have been handed down by watchmakers.

Breguet CEO Marc A. Hayek’s “authentic ode to femininity” became even more luxurious in October 2012 in Naples’ Reggia di Capodimonte (Caroline Murat’s palazzo, now a world-class museum) as he celebrated both ten years of the modern Queen of Naples line and 200 years since the completion of the queen’s original oeuvre by creating a unique anniversary timepiece, along with a platinum jewelry suite comprising a ring, a pair of earrings, a necklace, a tiara, and, of course, the very special repeating wristwatch.

The unique piece white gold wristwatch measures 38.45 x 30.4 mm and is adorned with 330 blue sapphires. Time is displayed on a silver-plated gold dial (luxuriously set with diamonds and sapphires like the case) that showcases the hammers of the repeating movement at 11 and 1 o’clock.

The diamond heart of a gold, engraved rose between the hammers indicates whether the hour will be sounded or the mechanism is set to “silent.” The petite automatic movement displays true pioneering spirit: it incorporates Breguet’s fundamental research into the acoustics of repeating movements in addition to the brand’s own silicon hairspring, ensuring that this unique piece is also cutting edge in terms of modern technology.

Hermès, an inadvertent trendsetter

In 1912, precisely 100 years after Breguet’s first Reine de Naples, a bold young girl was responsible for Hermès inadvertently creating the French icon’s first wristwatch.

The story goes that Jacqueline Hermès, a third-generation member of the Hermès family (founder Thierry Hermès’ granddaughter), disliked the way she had to carry her small pocket watch, considering that it was not “handy” enough for her active leisure activities. She thus asked her father to encase it in a leather “pocket” that would allow her to strap it to her wrist.

Her father called it the “porte-oignon.”

The result is visible in a famous photograph (above), and in late 2012 (precisely a century later) La Montre Hermès honored its creation with a new “pocket” watch simply and playfully called – as Hermès is wont to do – In The Pocket.

In The Pocket allows the owner to decide whether it should be worn in the pocket, on the wrist, or around the neck, thus making a delicate link to Hermès’ illustrious past.

Patek Philippe’s first wristwatch

In 1868, Patek Philippe manufactured a very lovely and dainty timepiece on a yellow gold bracelet. Its rectangular yellow gold case was embellished with enamel and diamonds as well as decoration belonging to the highest jeweler’s art.

This beauty hides a tiny 6-line (13.5 mm) key-wound movement with a cylinder escapement.

Sold to Hungarian Countess Koscowicz on November 13, 1876, Patek Philippe’s first wristwatch was specifically conceived to be a wristwatch rather than a transformed pocket or pendant watch.

Forty-eight years later, Patek Philippe created its first repeater for the wrist. Naturally, this was also made for a woman. A five-minute repeater with two gongs built upon a Victorin Piguet ébauche, this complicated platinum specimen with a richly hand-engraved 33.8 mm case and integrated bracelet was sold to a certain D.O. Wickham in New York.

Unfortunately, there is just about no historical information on either Countess Koscowicz or Ms. D.O. Wickham, so it’s impossible to say if they were “well behaved” or not. However, they were without a doubt trendsetters.

But I’m sure they would agree that technology never sounded – or looked – so appealing.

* This article was first published on July 8, 2014 at The First Wristwatches From Breguet, Hermès And Patek Philippe Were Made . . . For Women.

You may also enjoy:

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

The International Women’s Day brought us two rich and worth reading articles on Q&P at once, thank you dear Elizabeth. Less images, less celebrities, less show-off watches from todays production but more ‘long long long copy text’ with excitingly entertaining story-telling. That’s really brave in the SMS-world of superficial short text information. I often wonder why so many watchlovers neglect the contribution of women in this field (e.g. it is so many times suspected that a WOMAN may have commissioned the Breguet 160 – why?; but everyone names it ‘Marie Antoinette’). Das ist schon bisschen creepy, oder?

And a short question from my side: Do we know where the first wristwatch is today? Or is the Murat watch destroyed and lost forever? Thanks again, und tschüss, Thomas

Unfortunately, no one knows where Caroline’s lovely repeating wristwatch is today. The photo I showed here is a new watch made by Breguet based somewhat on its description, but of course in no way exactly. We know it exists because it was in Breguet’s ledgers, but that’s all we know for now. What an exciting find that would be should it ever turn up!