by Bhanu Chopra

Most of us are working from home during this unprecedented time. As someone who often travels, this has been a time for me to reflect on how fortunate I have been to visit some amazing places.

One was my first trip to Israel in the chilly winter of 2019. While I spent most of the time in Tel Aviv for business during the week, I had few hours before I returned home on Thursday evening to visit Jerusalem. My colleague suggested a short visit to see the historically important sites in Jerusalem, but knowing my passion for horology he said he had a special surprise for me: visiting the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art (now known as the Museum For Islamic Art).

I immediately Googled the museum and fortuitously discovered that the L.A. Mayer Museum holds one of the world’s most horologically significant pocket watch, clock, and automaton collections, and the star of the show is Breguet No. 160, otherwise known as the “Marie Antoinette.”

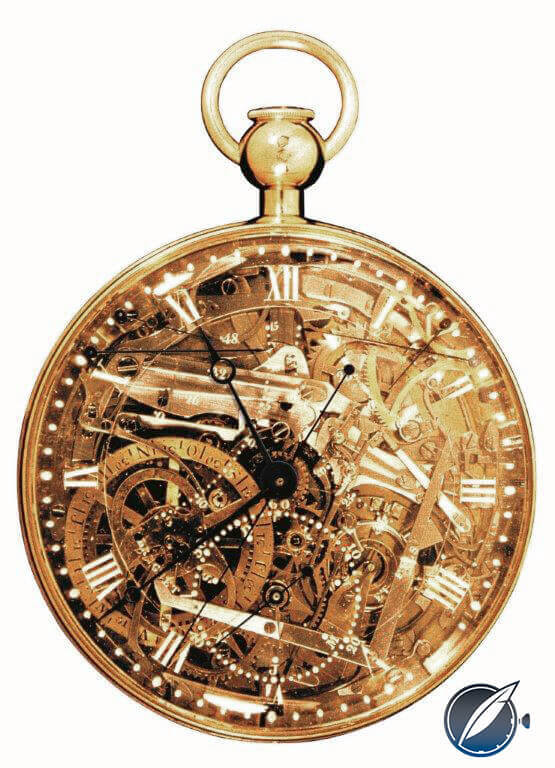

Abraham-Louis Breguet’s original pocket watch No. 160, commissioned for Marie Antoinette

It just so happened that we could not leave the office until later in the evening and then faced weekend traffic going into Jerusalem. The museum was open until 7 PM, and we reached it around 6:30 PM.

L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem (photo courtesy Jakub Grier)

As we walked through the front entrance, there were no lights or people around and I thought I had missed a golden opportunity to see the collection. But to our surprise, the door was open and a young attendant was sitting in the booth. We purchased our admission passes, and he told us to head down one level to see the watch collection and, graciously, to “take our time.”

Watch vault at the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art (photo courtesy Jakub Grier)

As we walked down the stairs, I noticed what appeared to be an old underground bank vault with a massive door weighing several tons. Having read the story of this watch in The Art of Time, co-authored by George Daniels, I understood why such security precautions were taken to protect the rare collection inside.

The theft and return of the Breguet No. 160 ‘Marie Antoinette’

On April 16, 1983, a thief broke into the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art in middle of the night and stole 106 rare watches and clocks. This theft has always been considered one of the most ingenious crimes committed in Israel.

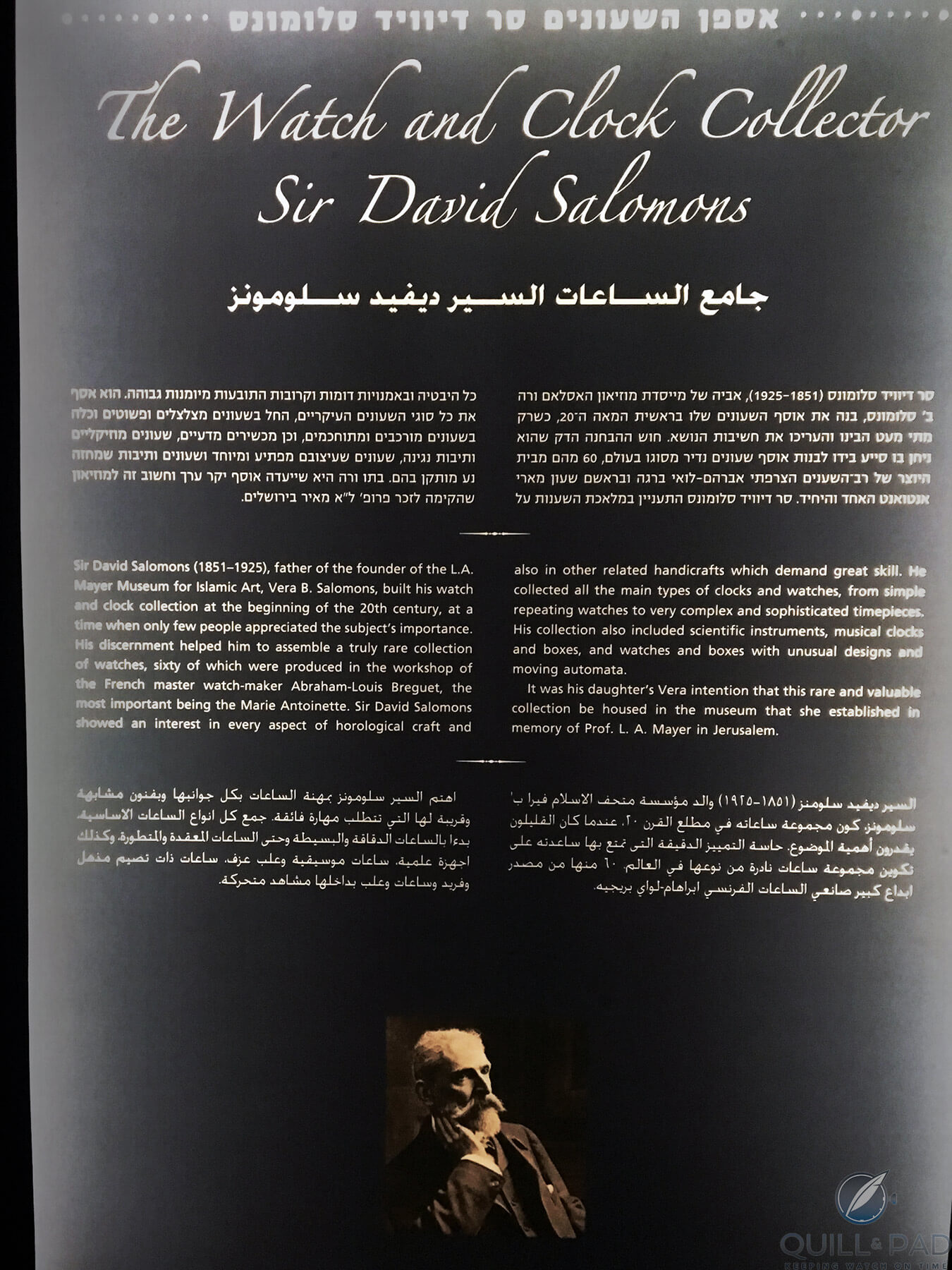

The stolen collection originally belonged to Sir David Salomons, the first Jewish mayor of London, and it was donated to the museum by his daughter, Vera Bryce Salomons.

Sir David Salomons and the collection synopsis, L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art (photo courtesy Jakub Grier)

Per Ms. Salomons’ wishes – she passed away in 1969 – the museum was founded in Jerusalem in 1974. She wished to establish the museum to cultivate peaceful relations between Muslims and Jews and to honor her friend, Professor Leon Arie Mayer, a prominent scholar of Islamic art and archaeology and professor at Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The L.A. Mayer Museum houses significant and rare Islamic cultural artifacts. There is no obvious connection between European timepieces and Islamic artifacts other than they are all works of art.

After two decades, the museum staff and Israeli police had given up on finding the precious watch collection. However, in August 2006 an art dealer from Tel Aviv visited Rachel Hasson, the museum’s artistic director, and informed her that someone was trying to sell pieces from the stolen collection in Israel.

Soon after, a woman named Nili Shomrat explained to the museum’s management that her deceased husband left some watches to her that may belong to the museum. She returned 39 watches and clocks, including some of the most significant watches made by Abraham-Louis Breguet.

One of the watches returned was Breguet’s No. 160, allegedly made for the queen of France, Marie Antoinette. See the entire story of this masterpiece, including the loss and return of No. 160, in Let Them Eat Cake: The Intriguing Story Of Marie Antoinette And Her Legendary Breguet Pocket Watch No. 160.

When the museum notified the Israeli police, their investigation broke open the 23-year-old case and began the process of recovering the missing watches and clocks. The thief responsible for this massive robbery was Naaman Diller, a well-known Israeli burglar.

Diller was married to Shomrat and had left all his loot to her when he died of cancer. Prior to his death, he confessed the stolen watches to his wife. Fortunately, he had only managed to sell a few pieces from the stolen collection. Most of the collection was found in a warehouse near Tel Aviv.

Singing bird pistol with timepiece by Frères Rochat, L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art (photo courtesy Jakub Grier)

Diller was so careful to hide the collection, though, that Israeli police had to cooperate with the French police to locate more than 40 watches and musical boxes in safes located in Paris. When all was finally tallied, out of the 191 total pieces from Solomons’ collection, 101 pieces had been stolen, 88 were recovered, and 13 have not been found to this day.

Now Solomons’ collection is displayed in the vault on the ground floor with no windows and an elaborate surveillance system. As I walked through the vault, I went straight toward the back where 55 pieces of Breguet’s most important work are displayed. The display itself is unique as the pocket watches are suspended inside the clear glass cases so that one may view them from every angle.

The Solomons collection, featuring the Breguet No. 160 ‘Marie Antoinette’

It was an overwhelming experience to see many of these sensational watches. And of course, the one that took my breath away was the Breguet No. 160.

Breguet No. 160, the ‘Marie Antoinette,’ L.A. Mayer Museum (photo courtesy Jakub Grier)

As the story goes, this very special automatic pocket watch was commissioned in 1783 by an officer of the guard in the court of the French queen, Marie Antoinette. It took Breguet 37 years to make and deliver the watch in 1820. Marie Antoinette never got to see the watch since she was executed in 1793, just a year after the French monarchy was abolished. The Breguet No. 160 is now unilaterally referred to as “the Marie Antoinette.”

In today’s terms, Breguet No. 160 can be classified as a mechanical super-computer. Only a master watchmaker like Breguet and the skilled technicians in his workshop could design and create a watch so sophisticated; it demonstrates Breguet’s unparalleled ability to construct watches with complex movements and multiple applications.

Apart from some steel movement parts, the metal on this watch is entirely gold, with the case surface set with sapphires. The front and case back are made of rock crystal through which one may appreciate the movement finish. On the side of the case is another engraving, Breguet’s secret signature, marked “Breguet No. 160.”

Breguet No. 160, the ‘Marie Antoinette,’ L.A. Mayer Museum (photo courtesy Jakub Grier)

The rock crystal dial is painstakingly engraved with Roman numerals and the “Breguet et Fils” signature. The hands – including the jumping hour hand – are made of blued steel. A display on the left is devoted to the equation of time and a 48-hour power reserve indications, while on the right we find the date and a thermometer scale.

Other functions include a minute repeater that strikes hours, quarter hours, and minutes on command as well as a full perpetual calendar showing the date, the day, and the month respectively at 2, 6, and 8 o’clock.

After spending several minutes in front of the Breguet No. 160, I went down each row to see more amazing work by Breguet such as a marine chronometer, a quarter repeater, a tourbillon, and equation of time watches.

Jaquet Droz singing bird circa 1790, L.A. Mayer Museum (photo courtesy Jakub Grier)

Aside from the Breguet collection, the museum also holds fascinating musical boxes, automata, shelf clocks, grandfather clocks, and scientific instruments like compasses, barometers, solar clocks, and telescopes by other masters of their crafts.

Quarter repeating Jaquemart watch, L.A. Mayer Museum (photo courtesy Jakub Grier)

Particularly fascinating were complicated watches and clocks with beautiful enamel work made in eighteenth-century Europe for the Turkish market.

We spent over an hour in the vault uninterrupted, exploring the watches and horological objects. As we exited the museum to visit the historical Western Wall, the attendant offered us a couple of postcards featuring a picture of Breguet’s No. 160.

As I sit here in my home office, admiring the postcard, I am already pondering my next visit to Israel. A single visit to this fascinating museum does not do it justice!

For more museum information, please visit www.islamicart.co.il.

Quick Facts Breguet No. 160

Case: 63 mm, yellow gold

Dial: rock crystal

Movement: automatic Breguet “perpetual” caliber comprising steel and gold components; Breguet natural escapement with cylindrical gold hairspring

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; perpetual calendar with date, month, and weekday; power reserve indication; equation of time; mechanical thermometer; minute repeater

Limitation: one unique piece

Insured value: $30 million

You may also enjoy:

‘The Grand Complication’ By Allen Kurzweil Delves Into The Mystery Of Breguet’s Marie Antoinette

Breguet Supports Versailles’ Marie Antoinette Exhibit At Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum

You Are There: Breguet’s Art And Innovation In Watchmaking Exhibition

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!