by Ashton Tracy

Since the dawn of time (well, almost) watch brands have charmed us with the allure of precious jewels in their movements.

At one time this went further than just advertising their inclusion in an accompanying booklet. Some manufacturers ventured as far as printing the number of jewels in the movement on the dial, a conceit that that has thankfully practically disappeared.

Vintage Jaeger “Panda dial 4 ATM”: proudly professing it has 17 jewels in the movement

Seriously, who cares how many jewels their watch has?

You’d be surprised.

Having spoken to watchmakers with many more years at the bench than myself, I came to realize that the confusion around jewels in decades past was a hotly debated topic. I’ve even been recounted tales of customers accusing watchmakers of stealing the jewels from their watch to fund their lavish lifestyles!

My personal favorite is the story about the customers who sternly informed their watchmakers they would be counting the jewels once the watch was returned from repair. A friendly warning, just in case they were thinking about pocketing them.

While some customers may have believed their watches made use of precious stones that in some way contributed to the value of the watch, the reality is that watch jewels are (practically) economically worthless.

So what is the truth about the jewels and why do they matter so much?

The answer (as so often) is friction.

Friction is the enemy of the watch movement as watches are required to work on a scale that most of us can not even comprehend.

Rolex’s Parachrom balance endstone shock protection in Caliber 3135: of course a ruby jewel

When manufacturing pivots for train wheels and balance staffs, tolerances are generally 5 microns either side of the actual number. Five microns is equal to 0.005 of one millimeter. Yes, of one millimeter.

So reducing friction is necessary to ensure top performance for a watch movement. And this is done by setting such watch components in bearing jewels instead of having metal rub metal.

“Boules”

The jewels that we use in watches today and decades past are synthetic, the most common being synthetic ruby. These jewels are grown in a controlled environment as something called a boule, the French word for a cone-shaped chunk of the material.

The ruby jewels must then be milled, sawed, and polished into the desired shapes, which is time-consuming and difficult, necessitating the use of diamond-tipped tools.

Where the natural rubies would have impurities called inclusions that made them difficult to work with as a bearing jewel, when grown in a laboratory setting inclusions do not occur: the grain in the jewel is minimal and they can be polished to a very high standard.

On the Mohs scale of hardness both synthetic and natural rubies rate at 9. Diamond is the hardest material on the Mohs scale, coming in at a rating of 10, making synthetic rubies a logical, cost-effective choice as a bearing jewel.

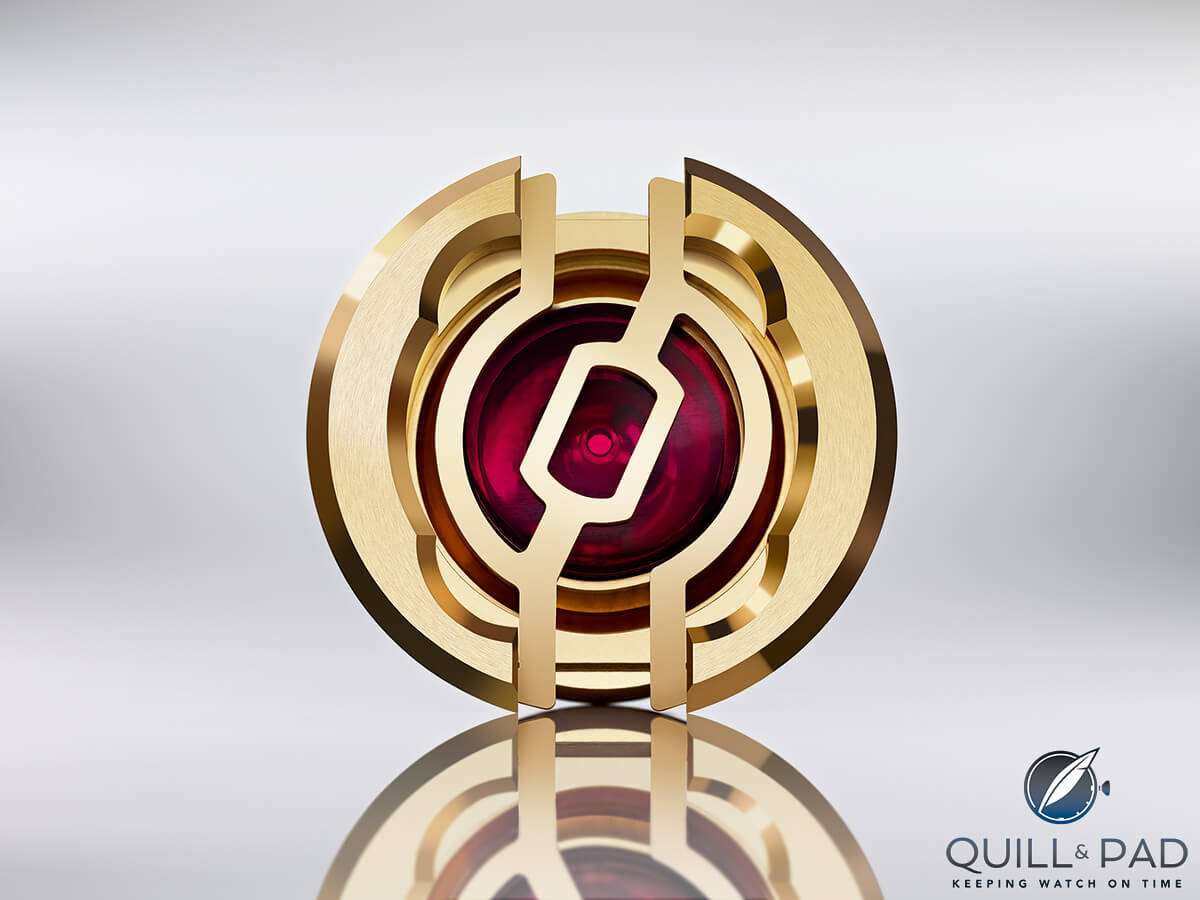

Synthetic ruby bearing jewels set in gold chatons in the movement of Raúl Pagès’ Soberly Onyx

Modern watch jewels

Jewels today are friction-fit into main plates and bridges, however that process only began around the 1930s.

Before then jewels were “rubbed in” to a brass setting. The great disadvantage with this style of jewel setting is the time and effort needed to replace them.

Modern friction fit jewels are just pressed in and out with ease, but with a rubbed-in jewel great care and time must be taken to burnish the new setting.

Contemporary watches utilize jewels in a variety of areas, including as pivot bearings for wheels, automatic winding components, and calendar mechanism as well as pallet stones.

The gear train wheels of a watch are the means of transmitting power from the mainspring to the escapement. In order to make that process as efficient and friction free as possible, jewels are used as bearings for the pivots of those wheels. Steel or brass bearings would cause excessive friction, thus consuming unnecessary power from the mainspring.

The use of jewels in combination with the highly polished steel of the pivots drastically reduces that friction.

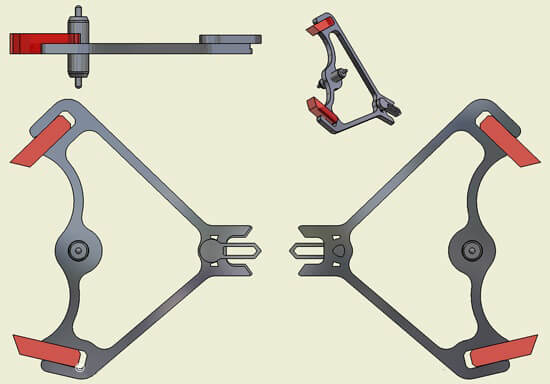

Romain Gauthier’s triangular anchor with ruby pallet stones

The same is true for the escapement lever’s pallet stones, which work against the highly polished steel surface of the escape wheel teeth and reduce the friction experienced there.

Balance pivots use jeweled bearings, though their setup is slightly different: they utilize a standard-style train wheel jewel bearing except that it has metal seating around it. That metal seating holds another jewel in place that is positioned on top of the balance pivot, keeping the lubrication for the jewel in place but also greatly reducing friction.

Watches of a higher quality, such as those receiving C.O.S.C certification (or higher) are manufactured to a higher level of precision. One area this particular aspect stands out is the spring barrel.

Traditionally, barrels would have brass bushings as bearings for their arbors on the main plate and barrel bridge. However, a watch manufactured to a higher tolerance would swap those out for jeweled bearings.

Assembling a patented ruby link constant force chain for Romain Gauthier’s Logical One

Other areas in which movements utilize jewels is the calendar work. In examples such as Rolex’s calibers, the jewel is used to reduce the friction when a lever actuates against a steel cam to ensure the watch changes exactly at midnight. The jewel is mounted on the lever, thus reducing friction with the result being a smooth, precise date change.

Ruby jewels are also used for the roller jewel. The roller is positioned on the underside of the balance wheel and has an impulse jewel, which swings back and forth in an arc, engaging with the pallet to allow the release of energy. The jewel for the roller is combined with highly polished steel of the pallet fork to again reduce as much friction as possible so the watch will run at peak performance.

The automatic rotor also is an area where friction consumes power, which causes the watch to not wind as efficiently as possible. In some movements, ball bearings are used to increase the winding efficiency, but in calibers that use an axle, jewels are employed.

The axle is generally seated against two jewels that are fitted into the upper and lower bridges of the automatic work.

Movement detail of the Vacheron Constantin Malte Squelette showing automatic winding system elements and an attractive selection of ruby bearing jewels

Jewels can also be used in countless other areas of more complicated watches such as chronographs, minute repeaters, and countdown timers.

Unfortunately, your synthetic rubies won’t be funding your next trip around the world trip, but they do play a vital role in the accuracy of your watch, making these little gems truly precious.

* This article was first published June 29, 2018 at The Number Of Jewels In A Watch Movement Indicates Value, Doesn’t It? A Myth Debunked.

You might also enjoy:

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] Primero, la entrada en Quill & Pad explicando el número de rubíes que portan los calibres, y si justifican el valor de un reloj: The Number Of Jewels In A Watch Movement Indicates Value, Or Does It It? A Myth Debunked – Reprise. […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

It was an interesting article to read, with the reasons why synthetic jewels are used in combating friction, but tell me, was the question in the title of this article ever really addressed as to the amount of synthetic jewels used and if more or less of them in a movement contributed value, or not?

In other words, it seems that value can be more than the financial value of the jewels.

That is exactly right: the bearing jewels in a watch have no bearing on the value of it whatsoever actually (see what I did there?). What you can take home from the number of jewels is that the more of them there are, the more “complicated” a watch is, meaning it has more functionality, which might in turn have an influence on overall value. The value of a wristwatch is determined by things like precious metals, gemstones (if any), degree of work done by hand, and in today’s world the brand making the watch. The synthetic ruby bearing jewels inside the movement do not influence a watch’s value or price by themselves.

Nice read, thanks!

As a collector of pocket watches and marine chronometers, I can only say that jewels are useful … in moderation. Standard chronometers such as used by the Royal Navy habitually made do with 7 jewels and were really very accurate. I like to contrast that with the first wave of Swiss watches that ended up destroying both the British and American watchmaking industries towards the end of the 19th century, when jewels were actively promoted as sure indictors of quality and accuracy to such an extent that makers even added them, quite uselessly and in vast numbers. One pocket watch I used to own proudly advertised itself as having 35 jewels — for a mere three-hand timekeeper with lever escapement!

Nor did this bad habit die out until quite recently. I remember vividly handing a first-generation Lange 1 at a store in Munich, Germany, and being told by the sales attendant in hushed tones that it had 20-something jewels, and that this was a sign for superior German quality …

I’m sorry to tell you then that the sales attendant didn’t know what they were talking about. In my estimation, Lange never does one thing that is superfluous. Nor would Lange ever consider putting “extra” jewels in a movement. That is a vintage practice (as you noted, chiefly perpetuated by the Swiss) that is thankfully gone. No one today talks about jewels, which are functional instruments for keeping friction at bay. The sales assistant obviously was not well trained.

Oh, I know! The chap was utterly clueless. Sad to say, his display of ignorance talked me out of buying the watch. I still regret that ….

As a sidebar, is there any reason why jewels are always a shade of red? I own a couple of American pocket watches with blue jewelling, and I always considered that a most beautiful look….

Red, blue, and colorless are all colors of corundum (and have almost the exact same properties), so no actually. I think the reason is that historically watchmakers used real rubies, so red became the traditional color (hence the use of the word jewels for these bearing elements). Synthetic rubies are far better quality and more suited to this use because there is no fear of hidden inclusions or other flaws.