I’m a passionate guy. Or, more precisely, I tend to get extremely interested in topics that I haven’t had much exposure to but that overlap with my other passions. I even have developed a pattern of behavior over time in which I undertake an episodic deep dive into a subject sparked by a glancing exposure to a factoid or detail encountered while focused on something entirely different.

Writing articles for Quill & Pad might be the biggest culprit of these diversions: one minute I am double-checking a date for a random reference and an hour later I am knee-deep into the exhibitor layout of the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. Many of my informational detours are small, but some spark real passion – like finally delving into the craft, art, and science of gemstones and gem-set jewelry and their relation to watchmaking.

We have always talked about jeweled watches here, perhaps more intensively during the annual round-table GPHG discussions, where I often lament how little I know about the subject and so can only comment on appearance and design.

Colorfully gem-set Rolex Yacht-Master 40 in pink gold

Thanks to one of my more substantial detours occurring during the design and engineering of my next watch project, I became somewhat informed about gemstones and techniques related to the application of these precious stones in studying for the jewelry-heavy GPHG pre-selected categories. This new information has sparked a significant amount of passion for the topic and has me wanting to share some of what I’ve learned about one of the most beautiful sides of haute horology: gems and their settings.

Today’s article is by no means intended to be an exhaustive guide and instead will act as a broad-yet-detailed introduction with emphasis on definitions, some techniques, and a bit of focus on how to appreciate the myriad of gemstones found in watches (and jewelry) today.

Types of gemstones: precious and semiprecious

Let’s begin with the most important thing to know first: what are the different types of stones?

The broadest answer is that there are two main categories: precious and semiprecious. This non-scientific classification going back a couple millennia is used to separate four main gemstones from all others simply due to their historic rarity.

Jaquet Droz Grande Seconde Tourbillon Opal combines the beauty and rarity of a fire opal with a mechanical delicacy

The list of precious gemstones is easy to remember as it consists of only diamond, sapphire, emerald, and ruby. These four are traditionally considered the most sought-after stones, though in reality there are numerous semiprecious stones that are much rarer and highly coveted in their faceted form.

Semiprecious stones include all other stones or materials that can be cut or polished and used in a decorative piece of jewelry or ornamentation. This includes things like opal, amethyst, tanzanite, and garnet but also extends to organic materials like coral, amber, ammolite, and pearls. There is no definitive list of semiprecious stones as it is extremely varied based on naming conventions and separations based on rarity, color, and even treatment.

A great example of this is the mineral species beryl. This mineral generally composed of beryllium aluminum cyclosilicate takes on a variety of forms based on the trace inclusions within the atomic structure. When chromium or vanadium is present, that form of beryl takes on a green hue and is known as an emerald, one of the four precious stones. But when iron is present, it can be either an aquamarine or golden beryl, depending on the specific type of iron ions. If manganese is present, it could be pink morganite or the darker red beryl. All of these are semiprecious even though they are the same mineral species as the emerald.

The Fabergé Lady Compliquée Peacock Emerald makes fabulous use of Gemfields emeralds

So in discussing precious versus semiprecious it is only for identifying four specific stones among the hundreds of gemstones used for jewelry. The reality is that all the stones can be considered precious and are – compared to something like sandstone or granite – rare when found in nature.

But there is also another category, and one that some might disregard, but is very important to understand: synthetic gemstones.

These are exactly what they sound like: stones produced within a lab environment to either mimic or copy naturally occurring stones. This might sound like these are stones being pumped out on a mass scale, but the production of synthetic gemstones is still a highly specialized and complicated process roughly mimicking the natural formation, with certain types of manufacturing taking up to a year to create a crystal of usable size.

Synthetic stones are largely chemically and structurally identical to naturally occurring stones, though with a few key differences including the possibility of microscopic air bubbles or growth lines that indicate the process used and often being completely free of impurities unless they were added during the crystal formation.

In many ways this often makes synthetic gemstones visually superior to natural stones as they can be inclusion free and consistent in color and saturation (not to mention they aren’t dug from the ground in dangerous mines located in war-torn countries).

Can you tell that these diamonds are natural?

Yet that emphasizes that the natural variability is also what many like about natural stones: each one is unique and has its own character from the flaws of nature.

The most expensive and rare natural stones still exhibit consistent color, are inclusion free, and have no issues that would make for an imperfect stone. Many make arguments for and against synthetic, but given that they are growing in popularity due to the lower cost and high quality of the stones, they are already a major part of the gemstone industry.

Cuts of gemstones

I could continue for pages on the types of gemstones and the specifics of their varieties, but let’s move on to what makes rough minerals dug from the ground (or grown in a lab) a worthy investment: the cutting and grading of stones. Grading is the evaluation of color, cut, clarity, and carat weight.

Properly assessing the grade begins with the cutting and finishing of a stone. Rough stones can be graded, but it is often an estimate so that the cutter knows the ballpark to expect from the stone; a true grade will be determined once the stone is shaped and polished.

This is the most important step in creating a high-quality gemstone as an unskilled gem cutter can ruin the value with a misplaced facet, improper proportion, or simply mishandling during the cutting process, leaving chips and cracks or completely destroying more delicate gemstones.

There are a few main categories of stones based on how they are prepared: faceted, cabochon, and mixed. Within each category there are many options for cut shapes, but no matter what form a stone takes, it falls into one of these three categories.

Faceting stones is crucial to bringing out the beauty of the internal structure as it creates the ability for light to reflect internally, magnifying the radiance of the mineral and making the stone shine.

Faceted stones are further broken down into three more subcategories to differentiate the faceting strategy, which pretty much covers all possible shapes.

These three main subcategories are brilliant, step, and mixed. “Brilliant” is the cut used for most round gemstones as it follows a standard proportion ratio and faceting layout to create bright, sparkly, and reflective stones.

Uncut diamonds

Step cuts are usually found in the baguette and emerald-cut styles and use facets that meet each other at right angles, which highlights the colors and features of the stone instead of maximizing internal light reflection. The mixed cut utilizes both the step and brilliant-cut strategies and is often applied to stones that are custom designs or “fancy” cuts, meaning not round, oval, or rectangular.

A quick run-through of the most common cuts includes the previously mentioned baguette and emerald and expands with the cushion, octagon, square, heart, marquise, oval, pear, trillion, and briolette cuts.

Styles can also be modified based on the stone and these can also be standardized such as the square-modified brilliant cut known as the princess cut or the square step cut with beveled corners called an Asscher cut.

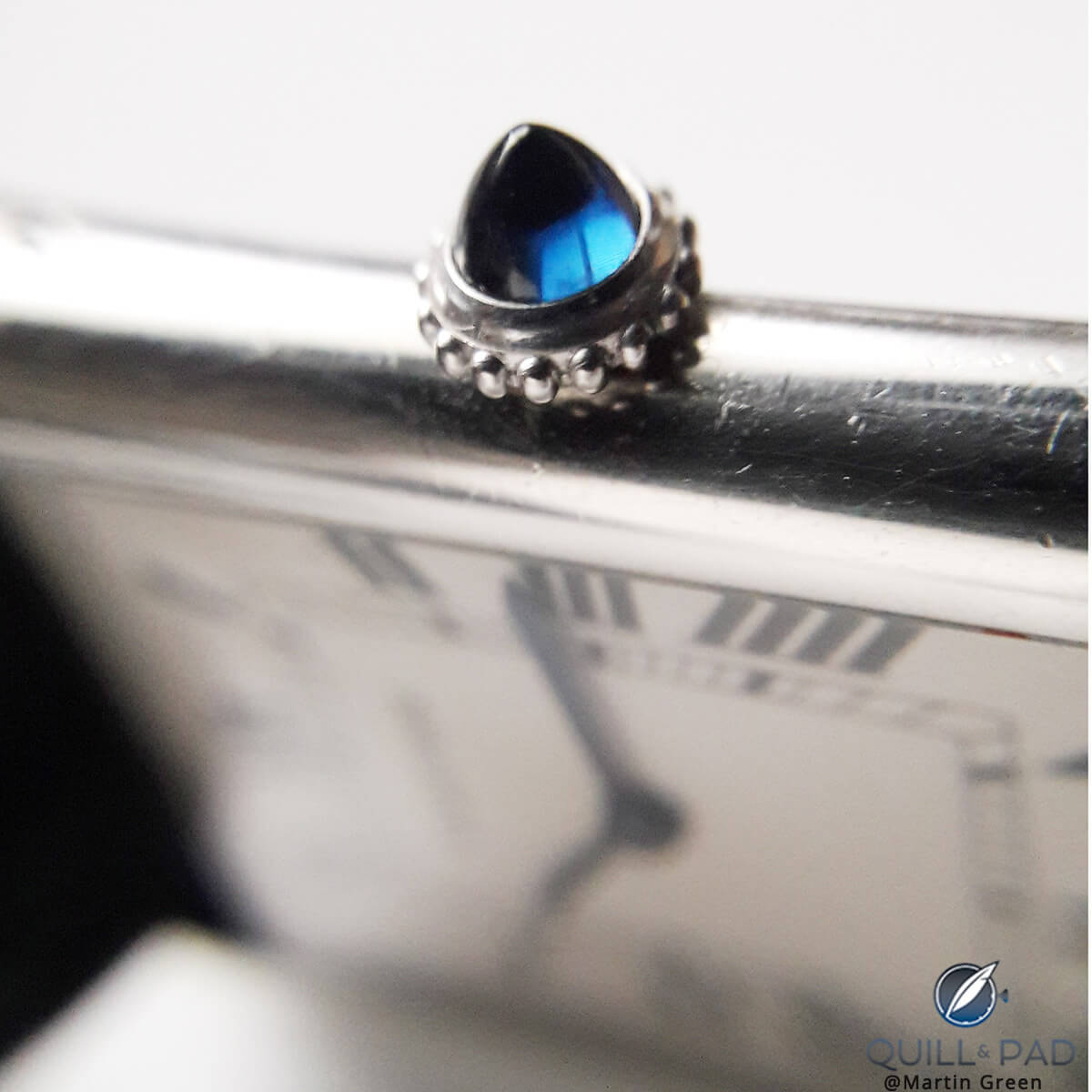

Cabochons are a bit of a different story. A cabochon is usually cut flat on one side and smoothly rounded or domed on the other, typically in a round or oval shape. We often see cabochons set into watch crowns.

The pointed blue sapphire cabochon of a vintage Louis Cartier Tank

This cut is often used for stones that aren’t necessarily translucent or transparent like an opal or a moonstone. Or a gemstone that has a high number of inclusions (characteristic flaws inside the stone).

As with the faceted cuts, sometimes cutters will shape a cabochon or completely facet the dome for a mixed style. One example of this is a sugarloaf cabochon, a square or rectangular cabochon that is softly faceted to a point, making a domed four-sided pyramid.

My favorite example of this is the gorgeous Van Cleef & Arpels Taj Mahal ring featuring a massive blue sugarloaf cabochon sapphire.

Van Cleef & Arpels Taj Mahal ring with sugarloaf cabochon sapphire

Beyond all of these are the vast unique creations of fancy and asymmetrical cuts that skilled gem cutters experiment with. Some become popular and get a name; others are specific to a single cutter. The possibilities are endless for creative gem cutters, allowing passionate jewelry lovers more options than they can imagine.

But it is only once these stones are cut that the value can finally be determined when the stones are professionally inspected and given a grade.

Gem grades: the 4 Cs

A large portion of colored semiprecious gemstones are never officially graded, either because they are too small or not the cream of the crop. But also because colored gemstones aren’t as easy to grade as diamonds.

These gems are given unofficial grades to help set a base price for lower to middle-end jewelry, but getting a certified gemstone is where the real value arises.

Diamonds on the other hand, have a much more specific grading system compared to other gemstones since they are usually desired to be perfectly white and as brilliant as possible. Many colored stones are appreciated for their uniqueness rather than their perfection.

All stones are technically graded based on four main attributes, the famous 4 Cs: color, clarity, cut, and carat. These standards chiefly apply to diamonds as the variety within colored gemstones doesn’t require as detailed of a grade.

The 4 Cs: color

Diamonds are graded according to two schools: the GIA (Gemological Institute of America) and the AGS (American Gem Society).The GIA system is more commonly used today.

Diamond color is graded on a scale of D to Z (GIA) or 0.0 to 10.0 (AGS). The best stones are perfectly colorless and receive a grade of D (0.0), while on the opposite end the stones can take on a visibly yellow hue when you get to a Z (10.0) grade stone; grade J (3.0) or higher denotes functionally colorless stones.

Colored gemstones are graded on the tone and purity of the main color (the redder the ruby, the bluer the sapphire and so on) and use a system based on two scales. The color is rated from 1 to 10, with 1 being the purest color and 10 being a mushy, bland color.

Colored gemstones rarely get better than a 3.5, which can be comparable to a D-grade diamond (so pretty much perfect).

How perfect are the Gemfields emeralds used on this Fabergé Lady Libertine I?

The tone is rated on a scale of 0 to 100, with a 0 being practically colorless and 100 nearly so opaque it is dark. This rating doesn’t necessarily denote a better or worse stone, it simply tells you if it is lighter or darker.

The ideal for vibrant dark-colored stones (ruby, sapphire, emerald) usually falls into the range of 65 to 85, while the typically lighter colored stones (topaz, aquamarine, citrine) should be between 20 and 65.

Color can be a bit of a debate as not every stone you see naturally started out that way. A wide variety of stones undergo heat treatments to achieve their color, either enhancing the natural hue or outright creating a new one.

Some may think this deceptive, but stones such as topaz and quartz (and even sapphire) are found naturally white/clear and nearly always undergo treatments to achieve their brilliant colors.

This does mean that naturally richly colored stones will fetch a higher margin compared to the treated stones, but by no means should one shy away from treatments. Heat treating should be declared when buying the stone.

The 4 Cs: clarity

Diamond clarity is graded on a 0 to 10 (AGS) or abbreviated scale (GIA) to determine the amount of visible inclusions in the stone. Inclusions can be foreign bodies, cracks, bubbles, or other minerals.

The GIA scale, which is the prevalent measure of clarity in the watch and jewelry industries, reflects the definitions of inclusions running from Flawless/Internally Flawless (F/IF), Very, Very Slightly Included (VVS1, VVS2), Very Slightly Included (VS1, VS2), Slightly Included (S1, S2), and Included (I1, I2, I3). Anything above a VS2 will look pretty much perfect to the naked eye.

Colored gemstone clarity is much different. Since many gemstones specifically have inclusions as features of the stone, using the diamond grading scale here would make most colored gemstones seem like low-quality stones.

Instead, these stones use a system of classification as a preamble and then a clarity scale that is only relative to that type of stone.

First, gemstones are categorized into three types: Type 1, which is typically inclusion free and looks relatively perfect to the naked eye or under a loupe; Type 2, which commonly has inclusions as a feature yet some of the best examples look clean to the naked eye; and Type 3, which is almost always included with even the best examples offering inclusions visible to the naked eye.

Three uncut emeralds from Gemfields

Emeralds fall into the Type 3 category, while aquamarines fall into the Type 1 category.

After sorting the gemstone species into the categories, a scale for relative clarity is applied.

Some use the GIA diamond scale of VVS, VS, S, and I or a different AGS scale that breaks stones down into Free of Inclusions (FI), Lightly Included (LI1, LI2), Moderately Included (MI1, MI2), Heavily Included (HI1, HI2), and Excessively Included (E1, E2, E3).

Stones in the excessively included category are often structurally unstable and usually not used for jewelry, but above that you can find really lovely stones in every grade. An M2 emerald (Type 3) can still be an heirloom-quality stone, though an M2 aquamarine (Type 1) will probably be a poor-quality stone with low value.

The 4 Cs: cut

Cut grading is based specifically on the type of cut and what are considered to be the ideal proportions of that cut. Diamonds and colored stones both use the same scale as it is based on the shape and has nothing to do with the type of stone.

The 0-10 scale breaks down to 0 (Ideal), 1 (Excellent), 2 (Very Good), 3 and 4 (Good), 5, 6, and 7 (Fair), and 8, 9, and 10 (Poor).

Symmetry and proportions play very strongly into how brilliant a cut stone looks as it alters internal reflection, so depending on the type of stone and the cut shape a stone with a cut grade of 6 in a round brilliant cut could look much more sparkly than a cut grade 1 in a baguette cut, even if the stone type and clarity are the same.

So while cut grading is still important, it plays different roles based on the cut shape and stone type.

The 4 Cs: carat

Carat grading is by far the most straightforward as it relates specifically to the weight of the stone.

Different stones have different densities so a dense stone in a one-carat weight could be much smaller than a less dense stone also cut to one carat.

For this reason, carat has more to do with how much of the stone is in each piece, and value is relative to that. Price jumps occur at every half-carat, so a 1.95-carat stone could be dramatically less expensive than a 2.05-carat stone.

When it comes to using stones in jewelry and watches, carat is the least important factor unless the stone is a centerpiece (or used for a solitaire engagement ring) as the cut shape and size is more critical to the actual setting of the stone.

The Graff Venus is the largest D Flawless heart-shaped diamond in the world at 118.78 ct: it was cut from a 357-ct rough diamond (at left)

Further grading can be applied to colored gemstones such as finish quality (perfectly polished faces, no chips on the corners of facets, consistent facet size) as well as brilliancy (the amount of flash that returns to your eyes) for a more detailed description of the basic cut grade.

A finish quality higher than a 6 (same 1-10 scale as cut) is preferred, and an average brilliancy higher than 50 percent (meaning at least 50 percent of the light is returned from internal reflections) means it will be a pretty scintillating stone.

Language nerd side note: “carat” and “karat” are often used interchangeably, but please note that the correct usage dictates that “carat” refer to gemstone weight and “karat” to gold purity.

Settings

Now that we know enough to appreciate the stones individually, we can begin to understand why settings matter and the application of stones is no trivial task.

There are thousands of variations on settings based on stone shape, type, and the structure supporting the setting, but they can be divided into five general categories: bead, bezel, channel, flush, and prong.

Look closely: the small diamonds surrounding the tourbillon cutaway on the Jaeger-LeCoultre Rendez-Vous High Jewellery Tourbillon are bezel-set

The bezel setting is believed to be the oldest style and consists of a strip of metal wire-wrapped around the shape of the stone and rubbed or hammered over the top of the edge to hold the stone in place, which is then soldered to the base.

Commonly seen with cabochon stones, a popular variation is the tube setting for smaller round stones.

The flush setting sees a piece of metal wrapped around the stone, while a hole for the stone is drilled directly into the solid metal. The hole is sized for the stone and once placed, the metal surrounding the stone is burnished over the edge to hold the stone securely.

This is also commonly referred to as shot setting, burnish setting, or gypsy setting and makes a very secure, very low-profile setting.

A fabulous example of flush setting fancy-cut diamonds: the attractive folding clasp on the Graff GyroGraff

The channel setting consists of a groove or channel between two strips of metal, or cut into a solid piece, with subsurface notches cut to hold the stones. Once the stones are set the metal is again hammered or burnished down to capture the stones. This type of setting is a fair bit more difficult than other settings as it requires precise tolerances to maintain the channel shape and hold the stones without them coming loose.

A platinum ring with brilliant-cut, channel-set diamonds (photo courtesy mappinandwebb.com)

The bead setting might be the most widely used in jewelry and requires probably the most prep work for any setting. It precipitates a precise hole drilled into the material to hold the stone. Then the sides of that hole and the area around it are filed and engraved away to leave a set number of edge sections intact.

The stone is then set into the hole and the intact sections are pushed over the edge of the stone with a graver to secure it. Then the remaining material is shaped a bit with a tool to round over the top, and the area around the stone is shaped a bit more. This extra work has the added benefit of making the areas around the stone reflect light in a variety of ways, visually increasing the stone’s sparkle.

The prong setting might just be an evolution of bead setting, or vice-versa, as it functions similarly but uses tall posts of metal to support the stone.

Found regularly on engagement rings – and very rarely on gem-set watches – the prong setting sees the posts notched to match the shape of the stone, a stone set between the prongs, and the tips of the prongs bent over the edge of the stone to secure it.

The Dazzling Jaeger LeCoultre Rendez-Vous Night & Day uses the prong setting to emphasize the larger stones around the outer perimeter of the case to beautiful effect

Then the tips or the post are cut off and shaped to finish the setting. This type of setting is usually the best at maximizing light within the stone since it can usually let light enter from many directions, not just the top like most of the others. It also is rather easy and quick to set, as well as easy to service later.

It is seen only very rarely on watches as it requires more room to execute properly. Jaeger-LeCoultre has taken to using the prong setting on its Dazzling Rendez-Vous collection of late, which has resulted in some serious added sparkle.

Setting variation

These settings all have thousands of manners of implementation, some resulting in much more complicated setting techniques than those they are based on. The ever-popular pavé setting is a form of bead setting in which an entire surface is covered in stones set very close to each other.

The MB&F FlyingT with an extreme pavé dial

This makes for a complicated preparation and very little room to make mistakes without compromising the entire piece being set. Snow setting is a variation on the pavé that uses randomly sized stones and avoids lining them up in rows for a more “natural” appearance.

Snow setting diamonds around a Hermès Arceau Temari case band

Another complicated variation is the tension setting, which is based on the channel setting. This type of setting sees a stone suspended between a gap in a ring or some shape and only supported within a small notch and held by the tension of the material. This is often the riskiest setting as the stone is most vulnerable to dislodging and being lost if the material moves, bends, twists, or expands and loses pressure on the stone.

Niessing is perhaps the world leader in tension setting

But nothing, in my mind, can compare to the most complicated setting I have seen: the invisible setting is derived from the channel setting and typically uses stones with straight edges like baguette cuts. Its appeal is mainly based on the fact that no metal can be seen between the stones so that it looks like a scintillating carpet of sparkle.

This setting avoids any visible retention technique and provides the smoothest and uninterrupted surface possible, but at a cost. Precision is the key with invisible settings, and there is no room for error. The invisible setting uses a set of rails machined into a recess that must be hand-shaped to create tiny flanges that interlock with a groove cut into the stone.

The unbelievable Chanel Première Tourbillon Volant with invisibly set baguette-cut rubies

The groove in the stone is very small and varies based on how it was added to the stone during cutting. The rails are fine-tuned to mesh with the stone before it is set.

One stone might be straightforward, but this setting consists of many stones set directly next to each other, so the tolerances for each rail must include the fact that another stone with the same tiny tolerances will be directly next to it. The best invisible settings are so precise that there is no visible gap between stones, meaning the underlying structure meshes perfectly with all the stones in the setting.

But the best/worst part of an invisible setting is how the stones are finally held in place. The stone is pressed or gently hammered down, causing the stone to deform the wings on the metal rails underneath, locking into the groove on the stone. There is no way to visually inspect the setting or modify it once the stone is set, one can only pry out the stone if there was an error, likely damaging or destroying the setting.

Invisibly set, baguette-cut diamonds carpet the floor of the Jacob & Co Astronomia

For this reason, invisible setting literally looks magical, making a pavé dial look like child’s play.

Gemstone application

The application of these stones in a watch dial, case, bezel, crown, or bracelet is where the real magic happens. With jewelry, mechanical precision is rarely an issue: so as long as the stones are secure and the finished product looks clean and even it is a success. But on a watch, one works with tolerances that cannot change lest they prohibit the watch from functioning correctly.

Also, depending on the chosen stone, some may be more delicate and easier to damage or destroy through rough setting techniques. Stones with a lot of inclusions, like emeralds or rubies, are particularly prone to being broken with a rough stone setter, so extra care must be taken compared to handling sapphires and diamonds.

A stone-set case is the easier option since the external surfaces are the least critical, but depending on the size of the case there may not be the needed thickness to the material, which can require the case to grow in size.

Compare the case sizes of the Greubel Forsey Balancier Contemporain (39.6 mm) and Diamond Set Balancier Contemporain (41.6 mm): the diamond-set version is 2 mm larger thanks to the sparkling addition

This is why some watches are slightly larger in the stone-set versions: the minimum material thickness needed to be maintained. Invisible settings are often used on bezels with square or baguette cut stones, which makes these simple components much, much more complicated to create.

A cabochon crown is fairly straightforward, though space is still needed in the center of the crown for the threaded stem to attach, requiring very careful application of the stone on the outside.

Stone-set dials can be relatively normal, though in very thin watches the thickness of the stones again becomes an issue. It is possible that the dial thickness needs to increase or the tolerance between the movement, dial, and hands passing over top need to be carefully maintained.

The Piaget Altiplano 38 mm 900D is a masterpiece in thinness, particularly taking that extensive gem-setting into account

Movement plates and bridges with settings are by far the riskiest application when it comes to the intended function of the watch. Most movement proportions cannot be changed for anything, so the stones need to be carefully selected to fit within the dimensions allowable, often leading to shallow cut shapes and a reduction in the brilliance of the stone.

Also, movements are usually not made in relatively soft precious metals but harder materials like brass or steel. These are harder to set stones in namely because most stone settings require burnishing, hammering, or engraving of the metal to hold the stones. Those actions can often alter the geometry of the components, possibly causing a failure of the movement’s function.

And that brings us to the most impressive technical achievement of stone settings in watches, settings in hard materials like stainless steel, titanium, ceramic, or even sapphire crystal. Some brands have invested a lot of effort to develop ways to set stones in these materials, though as the material hardness increases the settings are usually limited to a few specific shapes or styles simply due to the difficulty in the setting.

What a case: a Richard Mille RM 07-01 with carbon fiber case invisibly set with diamonds

A clever workaround has been to manufacture a recess into the very hard material, and then use a gold insert that actually holds the stones to create a bit of a hybrid setting. Though if anyone can figure out how to do an invisible setting, directly in ceramic, and not use adhesives (oh yes, adhesives are sometimes used) I will be astounded.

Gemstone appreciation

So now, knowing all of these details, I come to my conclusion: the appreciation of diamonds, gemstones, and stone-setting in watches. The craft of stone setting is as wide and varied as the stones themselves.

Choosing the right stones, cuttings, and settings can be a smorgasbord for designers and allow creativity to flow in every direction. But it also is easy to lose sight of what the stones are meant to do – provide added beauty – and overdo it with excessive settings or disconnected designs.

Design disconnect? The Jacob Co Epic X Chrono Messi Only Watch Special Edition with invisible-set sapphires

Like most design, restraint can often amplify the aesthetic appeal of something, so large applications of stones must be very carefully considered in regard to the overall effect the settings have. Every brand has its hits and misses, but the best among them consistently deliver beautiful and cohesive designs incorporating stone shape, brilliance, color, and their relation to the whole.

As I have learned more about difficulties with types of stone settings and the variety of stones, I have changed how I look at a stone-set watch and can now more greatly appreciate the hard work, craftsmanship, and ingenuity that go into each piece.

It also allows me to understand why I like certain pieces more than others, usually because they are good examples of a considered design.

Many out there may still disregard stone-set watches as too feminine, overly flashy, or simply too extravagant for their tastes. But I have come to greatly admire stone-set pieces and understand their place within the industry and within the larger landscape of jewelry, metalsmithing, and the history of decoration.

When you add all that together, it makes for a very interesting topic that I can deep-dive into all day.

For another take on diamonds in watches, check out Martin Green’s awesome Diamond-Set Watches: Who Knew Fine Craftsmanship Was So Complicated?

* This was first published on September 29, 2019 at Detailed Primer On Gemstones And Their Appreciation: An Introduction To The Finer Things.

You may also enjoy:

Diamond-Set Watches: Who Knew Fine Craftsmanship Was So Complicated?

Shrouded In Mystery And Fire: Opals In Jaquet Droz And Piaget Timepieces

Controversy Or Not? Synthetic Vs. Natural Diamonds In Watchmaking (Video)

Can A Man Wear A 60.66-Carat Diamond? The Roland Iten R60 Diablo Belt Buckle Says Yes

Hublot’s Dashing Diamonds: Classic Fusion Aerofusion Chronograph High Jewellery

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

A great write-up. Very thorough.

It’s worth mentioning that the rough guideline used by the second hand market to arrive at the estimated worth of any bedazzled wristwatch is to take the value of the un-bedazzled wristwatch and discount the gems entirely. You will never make back the premium you pay for all that ice.

That is very interesting, thanks for the information!

Your article is quite helpful! I have so many questions, and you have answered many. Thank you! Such a nice and superb article, we have been looking for this information about the concept in detail. Indeed a great post about it!!