Creator Conversation: An In-Depth Discussion With Ming Thein Of Ming Watches

by GaryG

Polymath: an individual whose knowledge spans a significant

number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies

of knowledge to solve specific problems (Wikipedia)

Do you know anyone who truly fits the definition above? I’ve had the privilege to know a large number of brilliant and talented individuals over the years, but for pure diversity of knowledge and thoughtfulness in applying critical thought across domains I’m hard pressed to think of anyone who fits the bill better than physicist, consultant, corporate executive, photographer, entrepreneur, and longtime watch buddy Ming Thein of Ming Watches.

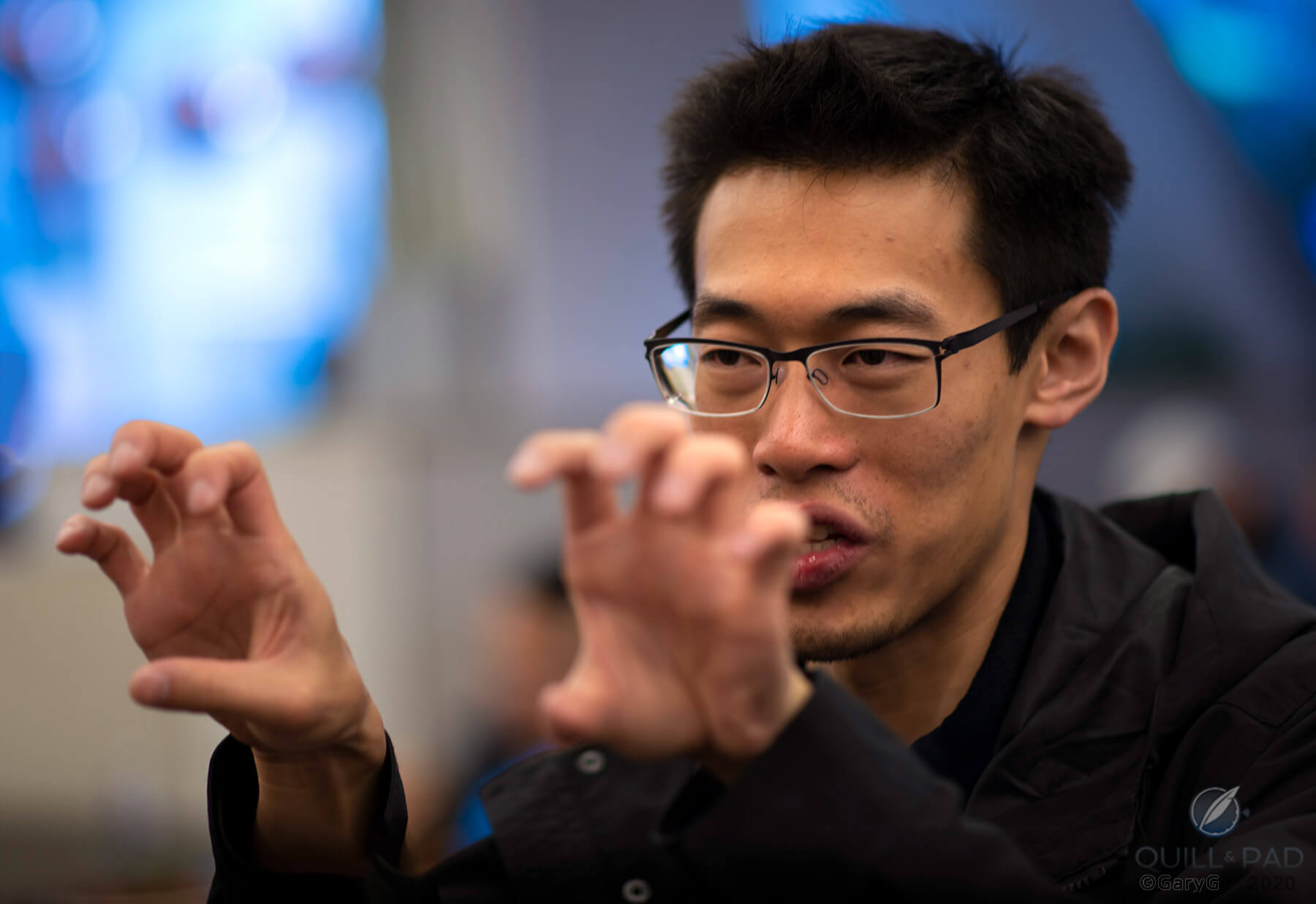

Ming Thein during a photography masterclass with the author, 2013

Recently, Thein was kind enough to discuss a far-ranging set of questions on his past, present, and future with me. What follows are what I consider to be the best of many highlights.

GaryG: Part of Ming lore is that you completed your university education at a very young age. I thought I was young when I finished my graduate work, but you make me look like a slacker! What was that experience like for you, and were there one or two key lessons you learned during that time that have continued to serve you well to the current day?

Ming Thein: I was basically too busy trying not to fail my exams to pay too much attention to what was going on around me! My time at university even pre-dated my interest in watches. But two things really stayed with me: first, I always felt that I had to make the best use of the time available; whenever I had the opportunity for free time, I felt the pressure to be working or figuring out how to do something better. I know that’s not necessarily healthy, but to this day when I have some time available, I am drawn to creating interesting results.

And I found that I struggled the most early in the curriculum when the syllabus was mandatory. Once I chose a concentration, I found that the things I was interested in became intuitive to me and therefore easier. Following your interests on that assumption is not necessarily a completely good thing, though: for instance, you tend to charge headlong into things like “you know what, starting a watch company’s a pretty good idea!”

Let’s start a watch company: Ming Model 17.01

GG: When we first met up, at least virtually, over a decade ago on the watch forums, you were clearly both a watch fanatic and a talented photographer. Which of the two came first for you and how does your photographer’s visual sensibility shape your watches?

MT: It might have been as long ago as 2001 or 2002! I had an internship and was making a little money and decided to look for a first “serious” watch that would tick all the boxes. Of course, we all now know that’s a fallacy; as soon as you acquire a watch it loses its Moby Dick status.

Before watches I was just a point-and-shoot film snapshot photographer, recording some of my experiences at university. As it turned out, both watches and photography were gateways to each other. But my fixation with finding out what that “one watch” was (an Omega chronograph I still own) was first.

Some of us used to meet in a friend’s flat in London to share watches, and in between I would visit watch boutiques – and photography was a way to prolong those experiences. What started as a piecemeal effort turned into something for which I became well known. After a stint in corporate life, I went pro as a photographer in 2011, starting of course with watches.

What I learned in shooting catalogue and promotional images for the big watch brands was that there’s a certain aspect to a physical object that a two-dimensional image does a very poor job of portraying. When an object contains reflective surfaces though, they overlap and interfere visually and give a sense of depth.

Being somewhat of a masochist, I decided that we needed to have this as a property of our watches. Tilting a watch and finding that it then has a completely different personality is what keeps it interesting, and visual layering is one of the most important aspects of our design language. Layering and the use of textures also makes the focal point of the dial clear; with both photos and watches, clarity of subject, including the hierarchy of intended viewing is really important; in our case, primary time display first, then secondary complication displays.

As with photography, composition is also critical. One thing that makes it much tougher with watches is that with an image you are composing in two dimensions, whereas with a watch it’s three – and you don’t know the angle from which the viewer will be seeing it. Early on I was doing design in Photoshop, but I had to learn how to use CAD software to be able to visualize in three dimensions from multiple perspectives.

Textures and layers: Ming Model 17.06 Monolith

GG: Speaking of composition and subject, in photography you’ve put forward the framework of the “four things” that make for a remarkable image (light, subject clarity, composition, the idea). Are there three to five “things” that make for a great watch and, if so, what are they?

MT: Oooh . . . that’s a good one.

There’s probably a nice parallel to be drawn between the redundancy/analog-ness of a still image (vis à vis a video clip) and a mechanical watch (vis à vis digital). They’re also both highly subjective in aesthetic preference; what I think is important might not necessarily be important to a fashion buyer or novice collector. Watches mean different things to different people, and I suspect that covers a broader gamut than an image, which is simply meant to convey the idea of the creator.

I think we all have a personally biased list for this, however. Mine would be:

- Originality – doesn’t look or feel like an imitation of anything else. Evolution is fine; duplication is not. But originality cannot also be simply for the sake of being different without any aesthetic or technical improvements.

- Aesthetics and dynamism – continuing on from “not just different for different’s sake,” it has to look good. This is perhaps the most subjective of all the criteria due to personal preferences, wrist sizing, wardrobe etc. I’d also argue that there are times when the difference between brilliance and a near miss is a really fine change of proportion or one or two lines more or less. A watch must be coherent. It’s also got to be legible: it’s a watch.

- Horological merit – this is a nice vague synthesis of points 1, 2, and 3 – perhaps equivalent of “the idea” in photography. Brains and beauty; an interesting movement with unusual aesthetics or function; and if there’s another way to read time, make it legible and at least somewhat intuitive.

An extension of this is honesty: I dislike watches that try to pretend or deceive into thinking they’re something they’re not; e.g., claiming a movement is “in house” by virtue of a rotor engraving, or subdials that are unnecessary, or give the impression there’s a lot more functionality than there actually is.

- Value – the concept of inherent value is very much what somebody is willing to pay. But the gap between that and what we as the creators feel it is worth can be large. I and everybody else like to feel like we’re getting more than we paid for, and I like to stay in business sustainably and have a healthy R&D budget to work with. Balancing those factors leads us to a price point, not working backwards from “what can the market bear?”

I really believe today that the majority of watch prices are out of whack either because of huge marketing budgets or profit margins or simple management laziness. This is reflected in discounting and subsequent lack of value on the secondary markets, which perhaps reflect market value better. Of course, some watches increase due to speculation or general recognition as “an investment” – if enough people believe it, it tends to become true. Unfortunately, this means pricing out a lot of potentially interesting pieces and loading them with unfair expectations at the price required to actually acquire one. A Daytona is a really solid piece at $10,000. It isn’t at $25-30,000. It’s important we do not confuse “value” and “price,” though. I’d be happy to pay $100,000 for a really unique grand complication, but not a steel sports watch.

Does it have the “Four Things”? Ming Model 19.02

GG: Let’s talk about organization. As a photographer you can to a large extent act as an individual; when you start making watches though, unless you are Philippe Dufour you need to build and manage a team. How did you pull together the Ming team and what have been the biggest organizational challenges you have had to overcome?

MT: The team was quite organic in that we had all been friends for a long time before we decided to make watches. I met Magnus Bosse on the PuristS around the same time you and I met, and the rest were members of the watch community here in Malaysia when I moved back in 2005. And the “newest” was one of my photography students I’d known for about four years before we launched the company.

The tipping point was at a watch show in 2014 when we decided that what we were seeing from other brands was not “what we signed up for” as watch enthusiasts.

One reason the team works so well is that we share interests beyond watches: cars, cigars, design objects, art, food, sim racing, and more.

Our team is dispersed across the world, and it took us a good couple of years before we established a workflow that functioned well for us. It’s now been over a year since we’ve had an in-person team meeting, which is a bit strange because many of the “a-ha” moments happen when we’re together, but we are coping with circumstances. It’s great that the members of the team have been so adaptable given our inability to leave our homes.

For me, the biggest challenge has been not trying to do everything myself!

Ming Thein (at right) and members of the prize-winning Ming team, Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève 2019

GG: You once told me that in watchmaking you believe you’ve found the one pursuit in which it’s easier to go broke than photography! What makes the path to sustainable profitability so tough, especially for a small independent brand, and how have you overcome some of the constraints and mitigated some of the risks?

MT: To start, I’ve now added motorsport to the list of least-profitable pursuits!

More seriously, like many businesses our biggest operating challenge has been cash flow. At the start, we went in thinking that we could price things less expensively than we actually could and still be viable; things like the need for spares and the cost of customer service were above our initial views. That led to another challenge: the need to make it clear to customers that watches at this quality level were not going to be priced at $900 anymore – it should have been double that or more from the start.

We also do a lot of R&D and initial experiments that don’t go anywhere, but that’s a critical part of our success model. And unlike many small brands, we have set up longer-term support and contingency plans to ensure that we will continue to support customers who have bought from us in the past during the warranty period and beyond.

Supply is a big challenge. As a small brand, we are right at the back of the queue with many suppliers. And we are buying many components, including some movements, on the secondary market where prices can swing wildly.

When demand exceeds the number of a given reference that we make, as with the Model 17.06, we can’t just go back and make more. We never make fewer watches of a reference than we think we can sell, but given lead times it is difficult to forecast demand precisely; and even components that would seem to be readily available often come in multiple sub-specifications, making some of the specific items we would need to expand production after the fact prohibitively expensive to source.

I’d like to add a tail-end chaser here: as a small brand without the marketing and advertising resources of the big guys we need to have a few aces up our sleeves. We always need to make something interesting, which drives R&D costs. And we need to give our partners and suppliers the most credit possible to ensure that we remain preferred partners for them.

Ming prototype watches sold at Phillips Geneva, November 2020 (photo courtesy Phillips)

GG: Just as Tesla started with the somewhat affordable Lotus-based Roadster before moving to the more expensive Model X and then diversifying its offering portfolio, Ming launched with quite affordable references and you’ve been progressing upmarket, most recently with the Agenhor-based chronograph prototype. How elastic do you think the Ming brand is regarding covering multiple product tiers and price points and do you see any risks in your strategy?

MT: Any strategy has inherent risks! I think we have been misinterpreted by the larger audience in some ways because the assumption that we’re going to be defined by our first products is incorrect. That’s one reason we went to a price point of around $9,000 with our second watch.

I like to think we can cover a variety of price points because our philosophy has never been about making watches for a price: it’s about making watches for value – the absolute best value at a given price point.

We’re also working to trickle down innovations from our higher priced items to more affordable parts of the line. So, for instance, you will be seeing some materials from our Agenhor-based chronograph prototype in new versions of the 17 series next year. I want to bring those sorts of things to a wider audience – and always bring you more as a buyer, both over time and in terms of production value at a given price point.

What we are doing also reflects where the members of the team are in our own collecting journeys. We have eclectic tastes, and one of our biggest challenges is to keep our watches interesting to us. This may point the way to some very small series of higher complications, both for our own interest and to demonstrate that we’re capable of more than people think.

GG: You’re my photography teacher, and my experience of your method is that it is highly Socratic – you allow me to struggle with an assignment before pointing out the errors of my ways and providing guidance. Is your own creative process similarly immersive and iterative?

MT: The design process is not so much Socratic for us; we do typically create multiple iterations, but the motivation is to avoid making mistakes. The photographic equivalent is curation; we leave a design on the wall, stare at it, and if we don’t like it, we keep changing it until we do. We typically do seven or eight major revisions and up to 15 minor ones before we make a prototype.

I do suppose that the way we work has become inadvertently Socratic: there’s no handbook about how to start a watch brand, especially one that doesn’t have other analogues in the industry. Hopefully our mistakes don’t kill us, and we learn and correct quickly enough to succeed. I like to think that our learning curve has been very steep, and I am aware that just because we have a model that has worked so far doesn’t mean that it will continue to work – I’m not that naïve.

Schwarz Etienne for Ming movement, Ming Model 19.02

GG: You’ve had great success working with supplier partners such as Schwarz Etienne and somehow convincing them to undertake very substantial modifications to their base products. What’s the secret to making that work?

MT: There’s not really a secret: it’s more about sharing the dream. I need to help them see what the end product will be and tell them they can do things others cannot to make the dream happen; that with them, it could be more.

We can’t tell them how to do their jobs; we can describe what we want and ask them whether it is possible and how they might do it. And regardless, we need to give credit for what others do; and sometimes things that are easy to overlook, like stabilizing the color of pink gold plating on a matte surface, are the toughest.

We seek out partners who will go above and beyond, and have stepped away from some others who will not; but when someone in Switzerland sends you a WhatsApp about an idea at 6:30 pm on a Saturday because they’re excited, it feels pretty good.

GG: To my eye at least, Ming is neither a traditional brand nor a Kickstarter-style micro brand, although it draws some elements from each. How do you create and sustain consumer engagement, and what are the primary differences between the Ming model and either of the bookend models I mentioned?

MT: We are a design firm first, but we are sensitive in that we understand the industry and how it works and the customers and their desires. We don’t make anything; we don’t commission full-blown products from contractors; we don’t outsource design; we don’t go out with a vague concept and ask for proposals; we don’t have traditional brand structures. Yet we have almost all of the benefits of an in-house manufacture with the Schwarz Etienne partnership and the flexibility to engage others as we wish.

In our view, people like us are our end customers; the entire experience has to be something that we would enjoy as buyers. Every single touchpoint and service component, from the speed of delivery to the quality of packaging to the number of times we contact a customer prior to shipment, is the subject of endless debate and fine tuning. We are transparent; we say it like it is and we deliver more than we promise.

When it comes to product philosophy, there are no “status” items in our selection; we don’t make pieces that are distinctive just to be noticed, but they may be noticed because they just look good. And given infinite resources, I wouldn’t expand volume for its own sake. nor would I just make small runs of highly complicated watches as I enjoy the challenge of making minimalist items that are interesting but still don’t break the bank.

Bank not broken: the author’s Ming Model 17.06 Monolith

GG: For whom do you create?

MT: For people like ourselves who still want to have the joy of discovery when they open that box.

That includes long-time enthusiasts like us, but also includes people who are entering the hobby with new eyes and don’t want something that’s just like what the rest of the industry is promoting.

It might even be someone like I was almost 20 years ago: researching, looking for that one piece that is going to be his first “really good” watch.

Expect a lot from us in 2021; it’s a full lineup up and down the range of prices with many new features and maybe a few world firsts. So far, we’ve made 30 references and significant variants in the past three and one-half years, and we have another 50 ideas on the board!

GG: Many thanks, Ming – I know I’m not alone in being very excited to see what comes next, and I really appreciate your candor and, as always, unique perspectives on our shared obsession.

For more information, please visit www.ming.watch,

You may also enjoy:

Ming 19.01 By Ming Thein, Unparalleled Quality For Price

Ming 17.03 GMT: A Brand On A Roll

Musing On The Ming Model 19.02: Micro Brand To Mega Brand?

Why I Bought It: Ming Watches Model 17.06 Monolith

Ming 18.01 H41 And 27.01: Revolution And Evolution

Design Your Own Watch? A Collector Explains The Pros And Cons With Ochs Und Junior

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Brilliant conversation gentlemen.

Many thanks for bringing this one!

Glad you enjoyed it, Alp! I’ve always found Ming to be a tremendously thoughtful fellow and it was a pleasure to be able to go beyond the “usual suspects” with our discussion topics.

Hope you are staying well, and that we’ll all be together again in person sometime soon!

Best, Gary

I have the Ming 17.06 copper and monolith ………happy with this , but comment on something that really has nothing to do with watches

a certain utuber , Paul Pluta,and followers, on the other side of the pond, Brisbane, i’m in Toronto

trashes anyone that owns Indie pieces , or dont have a hand in Patek or rolex

I DO HAVE A THERAPIST , and yes , he’s just a troll , leave it , ….but cant shake the guy off…any comments ?