by Ian Skellern

Blast from the past! This post is a “reprint” of an article first published on The PuristS way back in 2005.

Part 1: Felix Baumgartner and Urwerk

Many companies set out to wow the public at the annual Baselworld watch fair with luxurious booths, lavish parties, and very occasionally an innovative watch or two. Unfortunately, we tend to see much more of the former than the latter. Not because of lack of will, but evidence that even with the huge research and development budgets available to the big brands, conceptualizing and realizing something with a horological wow factor is no easy task. Too often we see the same old thing dressed in new clothes and being marketed as the next big thing with a massive publicity campaign.

Under then CEO Maximilian Büsser, Harry Winston Rare Timepieces took another approach; with its Opus series, it harnessed, nurtured, and promoted the incredibly creative talents of a few small independent watchmakers and, not surprisingly, managed to wow us five times in a row.

The Opus series was inaugurated with the Opus 1 by François-Paul Journe in 2001. Antoine Preziuso’s beautiful Opus II followed the year after. The year 2003 saw the totally original, innovative and crazy Opus III by Vianney Halter, which showed the risks and commitment Harry Winston was prepared to both take and make. Christophe Claret continued the series with his amazing musical Opus IV in 2004. For more on the Opus series see The Harry Winston Opus Series: A Complete Overview From Opus 1 Through Opus 13.

Harry Winston Opus 1 by François-Paul Journe

The Opus 2 by Antoine Preziuso for Harry Winston

The Harry Winston Opus 3 by Vianney Halter (with later help from Renaud et Papi)

Harry Winston Opus 4 by Christophe Claret

Each of these Opus watches generated enormous publicity and horological respect for Harry Winston, and the Opus V by Felix Baumgartner not only continued that tradition, it rocked the world of haute horology like very few watches before it.

2005: Harry Winston Opus V by Urwerk

Love it or loath it, the Opus V is not a watch to leave one feeling indifferent. So it may well be worth having a closer look at the team behind the project and the watch.

The Baumgartner brothers and Martin Frei

Felix Baumgartner and his brother Thomas are third-generation watchmakers – and you might nearly add a fourth as their great-grandfather worked for a watch company as well, although in the office not the workshop.

The Baumgartners grew up in Schaffhausen, where their father had a shop selling and repairing watches: this was a shop he had taken over from his father. One day, dad came home and surprised the family by saying that he had had enough; he didn’t like modern watches enough to devote his life to them anymore. He sold the shop and devoted himself to his hobby, which was restoring antique clocks in his atelier.

Felix Baumgartner presenting Urwerk at the AHCI stand at Baselworld 2005

The atelier was the room beside Felix’s bedroom. And with his father now working at home all day, Felix, at this time only seven years old, spent most of his spare time learning and helping his father. A few years later, Thomas (the older of the two brothers) started an apprenticeship with IWC as a precision machinist. Felix went on to study watchmaking at the renowned watchmaking school in Solothurn. Not surprisingly, he found he had a significant head start on his class mates.

In 1995, toward the end of his final year at watch school, Felix saw an advertisement from Svend Andersen, who was looking for a young watchmaker to join him in Geneva. The announcement read, “If you wish to be independent then now is the time to do it!”

Felix had no definite plans at that stage; however, he did feel strongly that he wanted to be an independent watchmaker like his father, and the magic word “independent” leapt off the page. He arranged an appointment with Andersen and traveled to Geneva for an interview. Despite Felix speaking no French at that time, they got on with English and German (Andersen is quadrilingual).

The interview went well and at the end of the meeting Andersen asked for Baumgartner’s CV; Felix had not prepared one as he thought his experience was not yet worth writing about. Andersen scribbled Felix’s name and phone number on a small piece of scrap paper, which he then placed on a tall pile of impressive-looking CVs.

Incredibly, that scrap of paper was not lost, and two weeks later Felix was offered the position. He spent the next two and a half years with Andersen.

“When Felix finished watchmaking school in 1995, he came to me to work as an independent watchmaker and learn French,” Andersen told me. “At that time we started making the famous erotic automaton watch (see Worldtimers, Erotic Watches, And Poker-Playing Dogs: AHCI Co-Founder Svend Andersen Has (Semi-)Retired, But His Brand Lives On), and Felix developed the technique for cutting out arm parts for the automaton figures and preparing them for painting (while also working more technically on a retrograde perpetual calendar). Felix worked here for nearly three years and started to experiment and develop the mechanism for his 101/102 watch.

“His interest was also in restoring old watches and see how they were made: a very important step for a creator. The last couple of years have seen him really develop as a exceptional watchmaker. The Opus V is a functional masterpiece, and Felix is a fine representative for the AHCI: he has a real ‘Academie’ spirit.”

While this was going on, Thomas had completed his apprenticeship at IWC and traveled to England where he spent a couple of years learning to restore antique English clocks and about their history. A short period in his father’s atelier followed before moving to Saint-Croix, where he worked for a few years with François Junod designing, constructing, and repairing automatons, including Jaquet Droz’s famous Writer android.

Thomas then moved to Geneva and set up a small atelier in which he continued to work for Junod as well as other clients. After a year, the brothers joined forces and opened up a new workshop together. Felix continued to work for Andersen; he also worked one week per month for Vacheron Constantin, which helped to pay his bills.

The brothers first discussed making their own watch around 1995 as something to do for fun. They had seen too many complicated watches on which they thought that reading the time was difficult because of the many hands on the dials. They decided to design and construct a minimalist, modern, and innovative watch. Basic sketches were drawn up of a watch with a traveling hour.

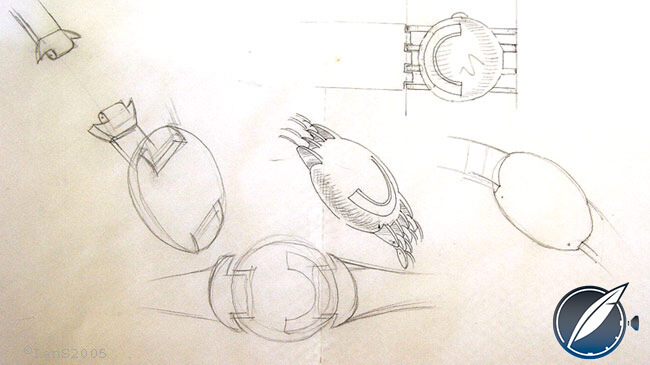

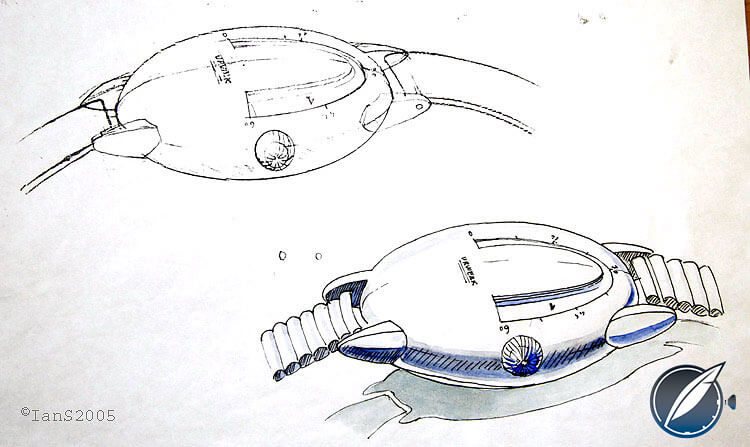

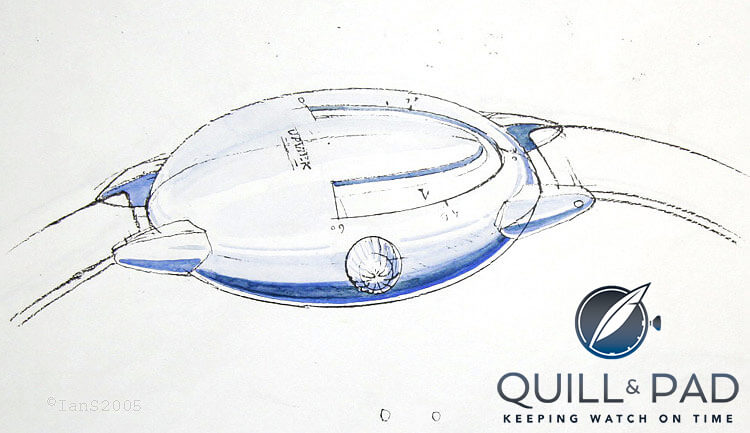

An early sketch by Martin Frei of what would become the Urwerk’s first watch, the UR-101

Martin Frei was an artist who had been a friend for years, though he was not just an artist. Frei was an artist who had loved and collected watches since childhood, therefore it was natural that the Baumgartners explain their ideas to him and ask for his input. Frei immediately grasped their concept and drew a few sketches, which the brothers loved. He had come up with a very distinctive and new design!

An early sketch by Martin Frei of what would become the Urwerk’s first watch, the UR-101

Slowly the sketches become slightly more refined and a look emerged. The Baumgartners built a steel prototype, which they showed to friends; the reaction was extremely positive . . . so they built another.

An early sketch by Martin Frei of what would become the Urwerk’s first watch, the UR-101

In 1997 Thomas and Felix Baumgartner joined Martin Frei, and with 20,000 Swiss francs (approximately $16,000) formed their own company called Urwerk. Their philosophy was to develop original and innovative new complications and to show that haute horology could encompass more than tourbillons and minute repeaters.

Svend Andersen was looking out for young watchmaking talent for the AHCI. He was worried that if the association did not recruit younger members as the existing members grew older it would just fade away . In 1997, with Andersen’s support and encouragement, they presented a brass prototype of the UR-101 (representing a gold watch) and a steel prototype of the UR-102 at Baselworld as AHCI candidate members.

The Geneva/Maltese cross compared with a star wheel

The original prototype had used a star wheel arrangement to turn the hour disks; this was similar to the one used in Audemars Piguet’s iconic Starwheel watch. They found, however, that the star wheel system, which has a spring under permanent tension on the wheel, had too much friction because of that tension, which caused it to use too much energy. This in turn reduced the power reserve.

View from the top of the Urwerk Maltese cross satellite system in the UR-101/102

They looked for alternatives and found that the Geneva cross offered a number of advantages: much less friction because there is no spring tension and no tendency to jump an extra step if turned too quickly. The Geneva cross system does demand much tighter manufacturing and assembly tolerances as there has be a slight play between the parts.

View of the Maltese crosses under the hour cones of the UR-103 orbital satellite mechanism

The terms Geneva cross and Maltese cross are interchangeable. Because of possible copyright concerns, Geneva cross is becoming more commonly used.

You can view an animation of a Maltese cross used in a stopwork mechanism to prevent over-winding at www.clockwatch.de.

The Geneva cross system requires more exacting fabrication tolerances, while the star wheel requires more precise regulation and uses more energy.

The UR-101/102 watches are minimalist in the extreme: no dial, no hands; nothing much that might lead you to believe it is a timepiece at all. A lonely hour digit moves across a semicircular arc, while discrete points mark the quarters and half-quarters.

Urwerk UR-101 “Millenium Falcon”

If the design of the case and complication was not enough to get you into orbit, the UR-101 was dubbed the Millenium Falcon, and the 102 Sputnik, with good reason: the traveling hour looks like a satellite moving across space. A variant of the 102 called the Nightwatch had a black, ceramic, anodized aluminum case with platinum back and luminous hour figures.

Urwerk UR-102 “Sputnik”

Even at that embryonic stage, and remember they had not sold one watch at this time, Urwerk created a minor scandal among the traditionalists with its avant-garde watches. While it attracted plenty of press coverage, sales did not exactly flood in. Though more sales came with the steel UR-102 watches, which went into delivery a year later.

Using the proceeds from those sales, the team built a gold watch. And 1998 saw Urwerk increase sales to two gold UR-101 watches and eight steel UR-102 models. The partners were overjoyed with the increased turnover and held a party held for each watch sold: luckily, though, they still had their day jobs!

From these small beginnings, turnover increased steadily and has roughly doubled each year.

2001: Urwerk Chronometer for the Goldpfeil Seven Masters project

In 2001 Urwerk made 200 watches for Goldpfeil, which not only resulted in more public recognition, it also introduced the brand to Christian Gros, who ran a small, extremely high-quality precision machining company specializing in watch cases and parts. Urwerk and Christian Gros formed a relationship that has endured and deepened to this day to the mutual benefit of both parties.

Urwerk UR-103 in yellow gold

The big year for Urwerk was 2003. Baselworld saw the company presenting its new UR-103 model, which replaced the discontinued UR-101/102 models. The 103 was a major evolution of the previous models as the hours were now shown by three-dimensional satellites at the bottom of the dial allowing for reading the time at a glance, i.e., without having to turn the wrist.

Urwerk UR-103 Control Board

The back of the watch saw the Control Board make its debut. This enabled Urwerk to keep the dial clean and clutter-free while providing useful (but not often used) complications. Innovative functions such as the precision adjustment displayed on the back of the watch enables the user to fine tune the watch’s regulation forward or backward up to 30 seconds per day. A 15-minute and second dial allows for precise time-setting.

The UR-103 was not only a much more sophisticated and upmarket evolution of previous models; it also attracted a much larger pool of clients and admirers . . . and among the latter was Maximilian Büsser, managing director of Harry Winston Rare Timepieces.

Part 2: Harry Winston Rare Timepieces and the Opus V

Perhaps emboldened by the very positive reaction at Baselworld 2003 for their new UR-103, the Baumgartners paid a visit to the Harry Winston booth and introduced themselves to then managing director Maximilian Büsser. While it may well have been a spur of the moment, friendly social call, the Baumgartners were aware that Büsser was a good man to know. The brothers were well acquainted with Vianney Halter; in fact they had acted as sponsors for Halter’s candidacy into the AHCI a few years before. Halter and Büsser were behind the mind-blowing Opus III.

Further discussions with Büsser followed in Geneva, and both parties’ interest in collaboration grew. Büsser wanted to alternate a crazy Opus model with a more traditional one. Halter’s Opus III was as zany and crazy as they come; Christophe Claret’s reversible Opus IV with tourbillon, cathedral gong minute repeater, date, and a huge central moon phase was a traditional model (in what other series of watches but the Opus could a watch like that be called traditional?). Büsser was on the lookout for someone who could think outside of the box to create the Opus V.

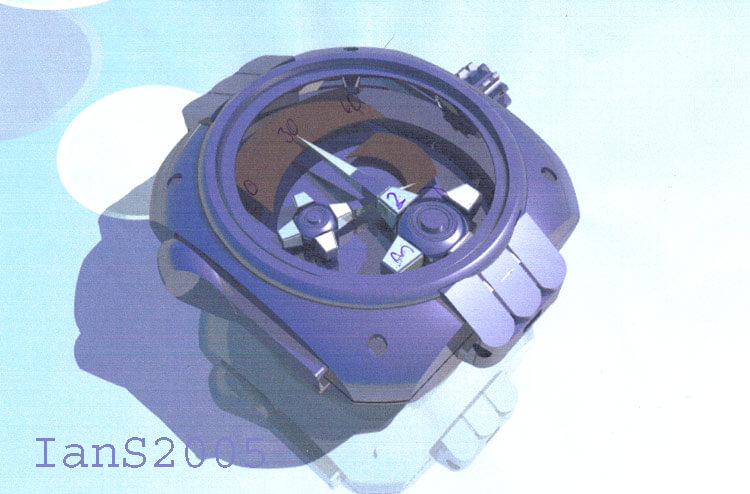

By the middle of 2003, Büsser decided that Urwerk had all the qualities he was looking for. Urwerk put three initial proposals to Harry Winston; the first was considered too risky in a technical sense to complete in the time frame available (see The Urwerk Opus 5 For Harry Winston That Almost Was); the second had the time going past on a type of continuous band; the third showed the little cubic satellites. The latter was the one chosen.

Early Urwerk CAD concept of a Harry Opus V case and dial layout

Frei drew up further sketches on the satellite theme, and finally the layout of that radical system was agreed upon. Büsser had stressed that central to the Opus series was the merger of the “DNA” of Harry Winston and the independent watchmaker. Feeling that the satellites represented Urwerk, they consequently searched for a complication to represent Harry Winston. As Harry Winston is well known for its use of retrogrades, the idea of a retrograde minute soon emerged – a decision Baumgartner nearly came to regret!

Suggestions and proposals flew back and forth, and by the end of the year the final design was agreed. The end result was very much a partnership with Harry Winston contributing essential design elements to the case, including the crown cover and the back of the watch.

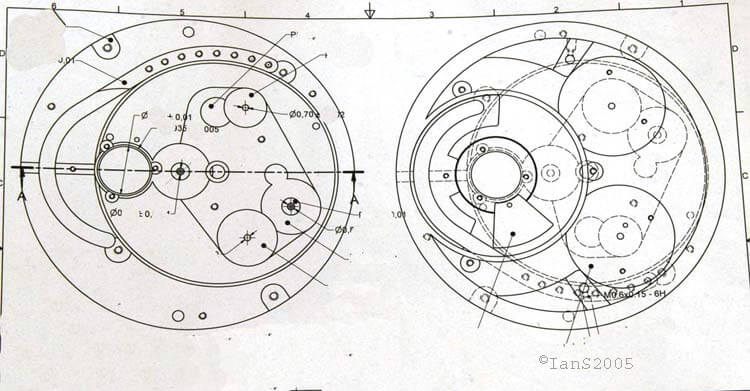

Technical drawing of the base plate of the Harry Winston Opus V by Urwerk

Urwerk and Harry Winston now had just over 12 months in which to turn a technical drawing of something never dreamed of before – let alone constructed – into a functioning and reliable timepiece.

Technical drawing of the dial of the Harry Winston Opus V by Urwerk

Here Urwerk’s relationship with Christian Gros more than proved its value. Thomas Baumgartner had decided to go back to a quieter life in Schaffhausen, and Felix, looking for a new atelier, moved into some spare space at Gros’s workshop. Having a world-class case and part-making precision machine shop virtually on tap, was vital to the quality and punctuality of the final product.

Christian Gros and Felix Baumgartner in 2005

Anybody under the impression that the use of modern CNC machines makes manufacturing parts child’s play may be surprised to learn that just programming, tooling, setting up the CNC machine, and making the 100 base plates for the movement took a team of three nearly three months. And that was for just one part!

Once the technical details of ensuring that operating the Geneva crosses on the satellites at 90 degrees to the norm was worked out, the satellite system progressed relatively smoothly. Baumgartner invented an ingenious and simple solution (now patented) for operating the satellites with Geneva crosses; the satellites function as their own crosses.

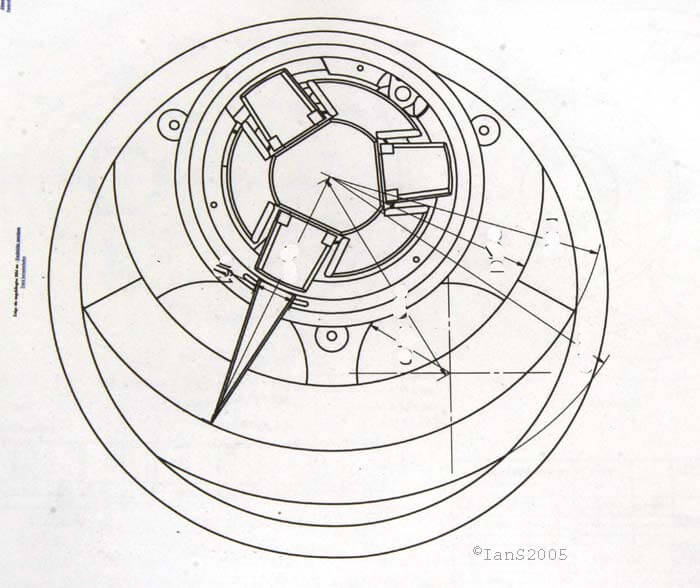

Proof of concept prototype of the hour satellite complication of the Harry Winston Opus V

The retrograde minute, on the other hand, proved much more troublesome. Retrograde mechanisms are traditionally controlled from the center axis; in the case of the Opus V, the center of the retrograde was occupied by another complication – the satellite system. Baumgartner knew of no other retrograde mechanism that dealt with another complication in its center and, therefore, had no technical reference to go by. This was breaking completely new ground.

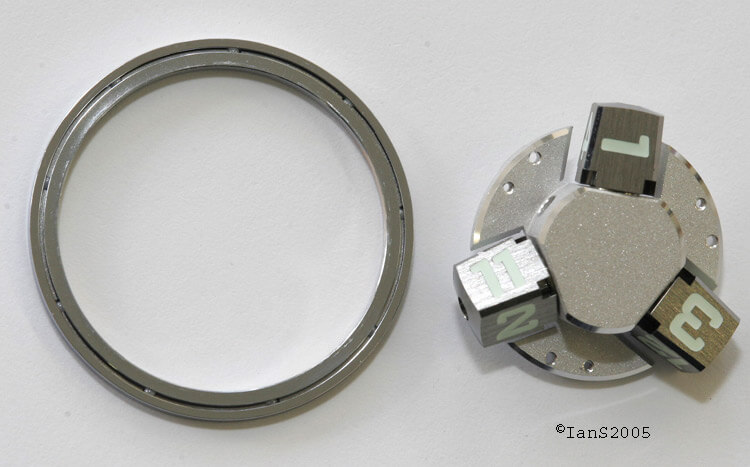

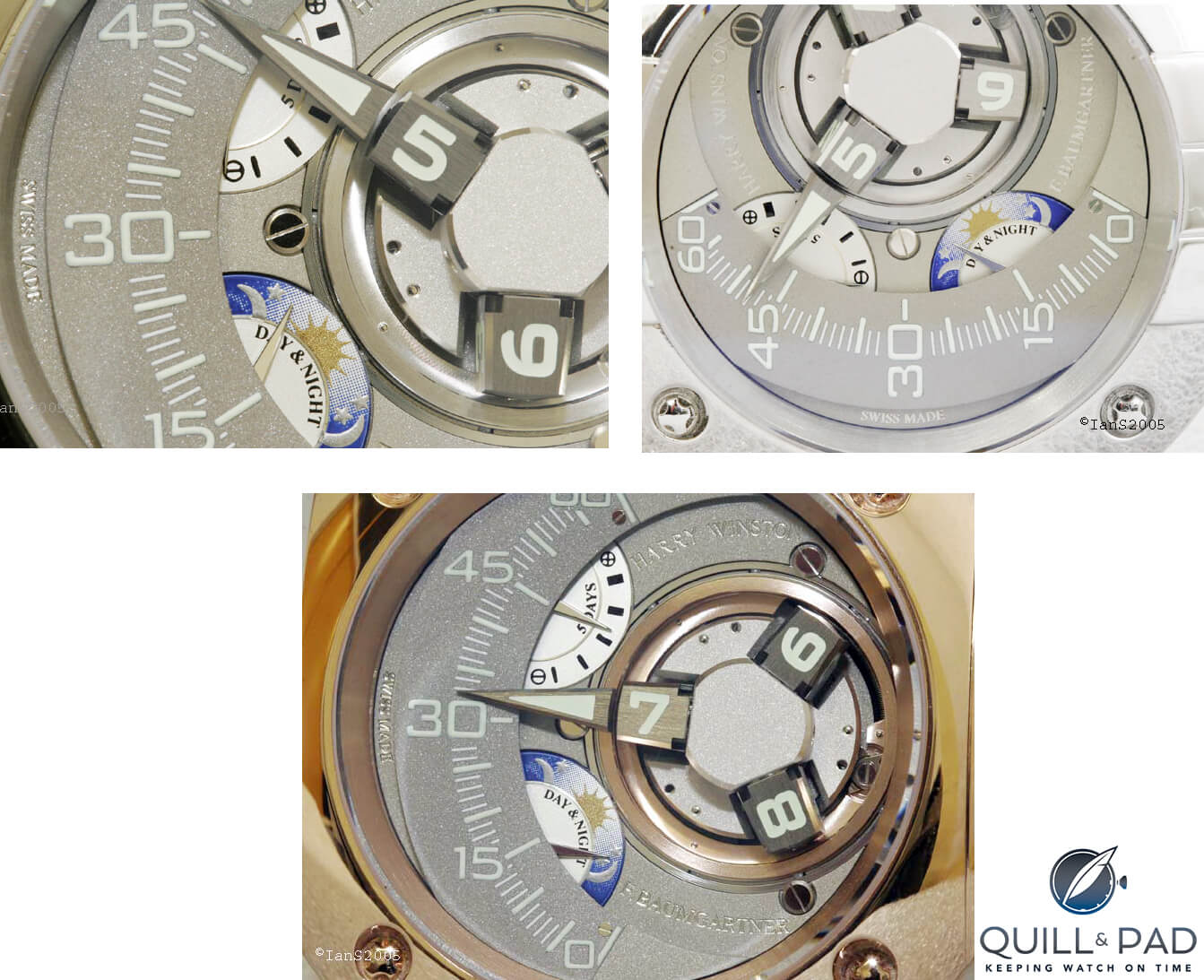

Harry Winston Opus V retrograde minute ring and hour satellite mechanism

Baumgartner had already solved the problem months before . . . on paper, that is. The minute hand would be attached to a large-diameter precision ball-bearing encircling the satellite system and powered by a double star. The problem was that specialist micro bearing manufacturers told him repeatedly that making a large-diameter ball bearing with such a thin cross section was impossible.

Impossible? The word isn’t in Baumgartner’s vocabulary.

Oversized-diameter retrograde minute hand mechanism of the Harry Winston Opus V by Urwerk

From a design sense, the minute hand is on the left of the hour indications for a number of reasons: firstly, technically it makes sense on the left; secondly, aesthetically it helps to balance the visual weight of the hour satellites on the right; thirdly, Urwerk’s research showed a strong preference for time indicators moving in a clockwise direction. Placing the minute hand on the left allowed Urwerk to fulfil all three criteria.

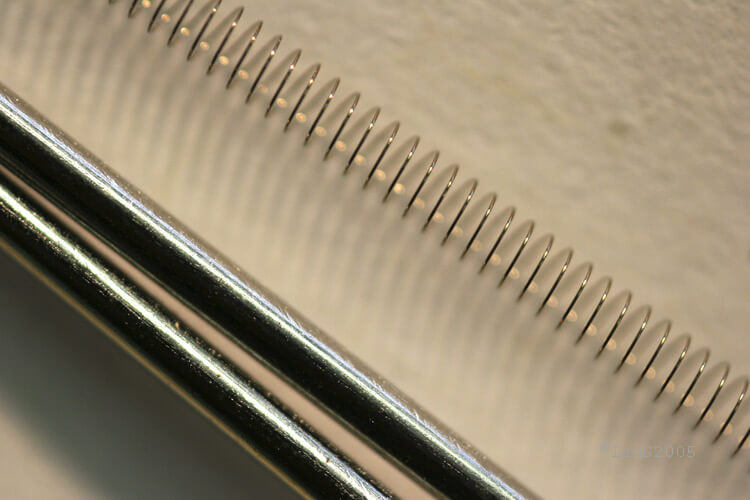

Eventually Baumgartner found someone who managed to develop the techniques to make the bearing. However, when it was trialed in a prototype, he found that the 12 mm (1/2”) traction spring that returns the retrograde – itself a non-traditional solution – was too strong; this caused large variations in torque across the arc of the minute hand and used far too much energy overcoming the spring. The solution was to make a spring with a smaller-diameter wire, however, they were already at the limit of the possible with a minuscule cross section of 0.1 mm (100 microns).

Retrograde minute traction spring for the Harry Winston Opus V by Urwerk inside a paper clip

He experimented with ever-decreasing wire diameters until he obtained the characteristics he needed at 0.05 mm (50 microns) or half what was previously thought to be the bottom limit. Unfortunately, to get those perfect springs meant throwing away 90 percent of them. Obtaining the traction springs needed for the 100 Opus V watches necessitated testing each one of a 1,000 springs and rejecting 900 of them.

Retrograde minute traction spring for the Harry Winston Opus V by Urwerk

Note: to put the diameter of the 50-micron wire of the traction spring in perspective, the average human hair is 70-100 microns.

As Felix Baumgartner explained, “Less than two months before Baselworld I was still not sure if I would be able to have these traction springs made to the specifications I needed. I was certain that the movement would work; however, there were a couple of little doubts at that stage as to whether it would work in time.”

The painstaking effort was worth it because the retrograde mechanism ended up using only 15 percent of the movement’s power. This, coupled with incredibly tight tolerances and precision in the manufacture and assembly of parts, resulted in the watch having a five-day power reserve. There are not many relatively “simple” watches around with a five-day power reserve, let alone one with a complex three-dimensional satellite system turning over two axes, an extremely large retrograde minute (possibly the largest ever made) moving across 120 degrees, a day/night indicator, a power reserve indicator, and a service interval indicator. This is a truly incredible feat and testament to the quality of design and construction.

Three specially shaped springs under the satellite system not only permit the whole system to be turned counterclockwise without damage, they also permit the deliberate playful bounce of the minute hand when it returns to zero.

Before and after finishing of the ARCAP base plate for the Harry Winston Opus V by Urwerk

Many parts have been machined from ARCAP P40 because it is an extremely resistant and stable alloy. ARCAP is a copper nickel alloy that is more stable (and expensive) than brass and does not corrode; brass is usually plated with gold, rhodium, or palladium.

ARCAP base plate for the Harry Winston Opus V by Urwerk

The special finish, in which the parts are micro blasted and then polished with a fine cashmere brush, is rewarding upon close examination under various light sources: sometimes it sparkles like a finely cut stone and sometimes like polished marble. This very distinctive finish make the indicators easier to read (with little reflected glare) and contrasts perfectly with the few highly-polished surfaces.

The massive looking minute hand is actually also made of ARCAP and has a hollowed out back. While titanium would have been lighter, Baumgartner preferred ARCAP because it was possible to manufacture the minute hand with an extremely sharp point and to use the same diamantée finish as the rest of the polished surfaces. Urwerk’s signature fine adjustment screw sits discreetly on the back where the owner can regulate the accuracy +/- 15 seconds per day.

Harry Winston Opus V by Urwerk

A close look dial side of the Harry Winston Opus V

Power reserve and timing precision adjustment screw on the back of the Harry Winston Opus V

Side and bottom views of hour satellites of the Harry Winston Opus V

Watchmaker Sébastien Billières assembling an hour satellite for the Opus V in 2005. At that time Urwerk’s watchmaking team comprised only Felix Baumgartner and Billières, who went on to co-found Genus Watches and win the 2019 GPHG Mechanical Exception prize for his Genus GNS 1.2

Complex case of the Harry Winston Opus V

This is what the platinum Opus V cases look like before machining

Harry Winston Opus V on the wrist

Part 3: The Urwerk 103.03

As if a project of the complexity of the Opus V would not be enough to keep anyone busy for a year or two, Baumgartner and Frei also found time to design and construct a major evolution of the 103. This watch, the 103.03, is in my opinion, their best model to date. While their previous watches have been space-age, minimalist, and functional time machines (with the emphasis on machine), the targa-shaped crystal on the 103.03 transforms it from watch that stunned because of its unique design into a truly stunning watch.

The 103.03 was a radical re-think of the Urwerk philosophy as well as the look. Until this model, the idea had always been to show only the absolute minimum on the dial. It was only as the design developed that Frei and Baumgartner realized how much more was added visually in showing how it all worked. The large crystal gives another major advantage over previous models in that it is much more resistant to scratches than a fully metal cover.

Urwerk’s strengths include the fact that designer Martin Frei does not come from a horological or technical background. Unshackled by knowing what is believed to be technically feasible allows his imagination to roam without limit; he can concentrate purely on art and form. To physically manufacture the complex crystal he designed for the 103.03 stretched the very limits of the possible – par for the course from Frei. Within the form of the crystal are a series of complex curves making production extremely difficult. The form first runs parallel to the rotating satellite and then flattens out slightly to match the reduced curve at the top of the case. Difficult by itself, that was actually the easy part!

Urwerk asked five specialists in crystal manufacture to make prototypes: four failed completely and one had only very limited success. The problem was cutting the inner bite from the crystal where it faces the crown. Whereas external cuts and shapes are relatively easy, internal cuts are extremely problematic. Further research and development meant that while these elaborate forms are now possible, the reject rate is still one in two. For every 100 watches Urwerk makes, it orders 200 crystals and throws half of them away.

Brass is one of the most common metals used in watch component manufacture; however, it is usually plated with gold, rhodium or palladium to minimize tarnish. Urwerk fabricates many components from ARCAP P40 instead. ARCAP is an extremely resistant copper-nickel alloy that is stabler (and more expensive) than brass and does not corrode like brass. That intriguing finish, made by micro blasting the parts then polishing them with a fine goat-hair brush, is a unique Urwerk specialty. In addition, the dials of the gold models receive a coating of black PVD, whereas the limited edition platinum models have perlage.

The look of the Control Board on the back brings us closer to earth, but not too close: just from outer space to a low earth orbit. The dials on the back are actually black; however, when caught at certain angles to the light, the anti-reflective coating on the crystal makes them look blue.

One unusual feature about the movement in this watch is that it is upside down. The minutes, seconds, and power reserve on the Control Board (back) are actually on what would be normally the dial side of the movement. The satellites on top are driven by a tiny 0.3 mm pinion that passes through a friction-fit hole in the center wheel.

The future?

And the future? Well, we will have to wait and see, though one thing is for sure: whatever else Urwerk has in store for us next year, it is unlikely to be boring. This is a company where thinking out of the box is just standard operating procedure and the impossible simply means trying again a little harder.

If Urwerk could come up with a watch like the 103.03 while developing, constructing, and managing a project like the Opus V, what might they come up with in a “quiet” year?

And that should have been the end of this three-part trilogy; however . . .

Part 4: The Urwerk 103.03 User Review

Urwerk UR-103.03 in white gold

As I was getting ready to leave from my last visit to Urwerk, I said something to Felix Baumgartner along the lines of, “I really like your 103.03, however it is a shame it is far too big for my small wrists.” He replied that he thought that the watch wore very comfortably on small wrists – including his own – and why don’t I take his (watch) home for a couple of weeks and try it out for myself?

Not needing to be asked twice (and worried he might change his mind), here I am a week later typing away with his white gold 103.03 on my wrist and sore facial muscles from a fortnight of continuous smiling.

Ian Skellern at “work” wearing a slim Urwerk UR-103.03

Warning! As I fastened the watch to my wrist in Urwerk’s atelier, I noticed from the corner of my eye a fleeting movement above and behind Felix’s workbench. Turning quickly, I was just in time to see the last vestige of my objectivity fly out the window. For those looking for, or expecting, a disspassionate and objective review, I wish you the very best of luck in your quest . . . because you will find precious little trace of that here.

Please note: the watch I review here is Felix Baumgartner’s own watch and is a prototype (due for a service). It does not have any anti-reflective coating on the crystal and please do not be too harsh if my images have highlighted any grime, dust, or scratches.

Urwerk UR-103.03 on the wrist

While I am an unabashed fan of this timepiece, I am not at all a fan of large watches. I have tiny wrists (17 centimeters or just over 6 ¾ inches) and I have never felt comfortable wearing anything larger than a 38 mm watch. In fact, when Felix made the offer, I was wearing a vintage ultra-thin Vacheron Constantin Caliber 103 that is 33 mm in diameter and so light that it would float off the wrist if not for the strap holding it down. Taking that off and replacing it with a 50 mm long, 128-gram time machine was a considerable shock to the lower arm . . . for about five minutes. After that, it felt like it had always been there.

The following comments were made after wearing the watch virtually 24 hours a day for two weeks. I have a fairly varied and active lifestyle – probably much more active than Felix realized – and the watch has accompanied me while working with horses daily (including cleaning stables), driving tractors, flying in helicopters, a dinner party, (suit and tie) business meetings, and press conferences. Not a typical fortnight, I’ll admit, however, the 103.03 never looked or felt out of place once. I found it a very comfortable, easy-to-wear watch in all those situations and I do not remember having ever worn a watch as versatile before.

Lume shot: Urwerk UR-103.03

By any standards, at 50 mm long, 36 mm wide, and 13.5 mm high, this is a large watch: yet I was surprised not only how well proportioned it looked on my wrist, but also how comfortable it was to wear. One problem that I have with larger watches is that the lugs extend straight out past the curve of my wrist; this usually results in either the watch either moving forward (down the arm) and the crown pushing into the back of my hand or it slides around my wrist and ends up upside down – neither of which has happened (or feels likely to happen) with the 103.03.

So why doesn’t it look so big? I believe that is due to two main design features. From the wearer’s main point of the view, the watch is only 36 mm across and it does not even have a crown out to the side, which usually makes that dimension look even wider. And while a thickness of 13.5 mm may seem substantial, this is only in the very center of the case: at both ends the case tapers down to the wrist giving an overall appearance of a much thinner watch. Usually it is not the diameter that makes a watch look big and bulky to my eyes, but the height.

Urwerk UR-103.03 in white gold

As the images above show, the 103.03 does not look like an oversized watch; however, does it wear like one? In a word, no. Even with my small wrists, the watch is very comfortable and wears like a much smaller model. I believe this is due to a number of factors:

1. While the watch is 50 mm in overall length, that does include the integrated lugs. The strap pins are “only” 43 mm apart, which means that the lugs do not extend past the curve of the wrist.

2. The strap is very wide (30 mm at the pins), which provides a very stable base and a comfortable feeling on the wrist. The weight is distributed over both a large surface area of watch and strap.

3. While looking at the case edgeways gives the impression that the base of the watch actually curves up and away from the wrist at each end, in reality it hugs the wrist by curving down and around it, resulting in a very snug and secure fit. This clever feat is made possible by placing one of the lugs below the watch and complementing that with an angled form jutting up to the large crown.

The impressive and tactile Urwerk UR-103.03 crown

Another big design feature is that massive crown. It is relativity discreet when seen from above as the crenelations match the grooves in the top of the case. The pleasure comes from viewing that imposing form from the back and actually winding the movement. I have never enjoyed winding a watch as much as this one and found myself wishing, for the first time in my life, that the power reserve was shorter!

While the winding mechanism has been especially strengthened to avoid any possible over-enthusiastic over winding of that large crown, I found that it is very easy to feel when the movement is fully wound as it stops quite clearly when it has had enough.

Expecting that telling the time would not be as intuitive as reading a classical watch, I was surprised once again. Within twelve hours of wearing the 103.03, I found myself not so much reading the time as simply noting the position of the satellite; much as we do when glancing at a normal dial. A major (and deliberate) advantage of Urwerk’s design is that you never have to tilt your wrist toward you to see the time; even when driving you can usually see very clearly where the hour satellite is and know the time at a glance.

Urwerk UR-103.03 views

Another unexpected result from wearing this watch has been that I have found that I do not usually need to know the time as precisely as I once thought. When wearing a watch with standard hands and dial, I am as fussy as anyone in checking the time against an atomic clock at regular intervals or feeling a little peeved if I am reminded that my watch is a couple of minutes out. While it it easy to tell the exact time if you feel you need it, with the the 103.03, I find myself in the habit of just looking at which fifteen-minute period it is in rather than bothering with anything more precise. Unless I have a train to catch, I can see myself needing no more than the hours and half-hours before long.

As much as I am biased towards the watch, in the quest for balanced reporting I have searched high and low for flaws . . . and believe I have found one, a very small one. While not everybody will spend as much time as I have looking at the Control Board with a loupe or macro lens, my own experience has revealed that it is fiddly to (perfectly) clean the edges of the dials where they meet the base plate. If the crystal was flat with the base plate, that “problem” would be eliminated.

While not at all ostentatious, especially in white gold or platinum, this is the first watch I have ever worn where I have noticed strangers surreptitiously glancing at my wrist trying to work out what it is I am wearing . . . and the braver of them even asking. Friends who would not blink an eyelid at a $300,000 repeater – because of ignorance, not being blasé – immediately want to know what the watch does and how it works, and it gives me much pleasure to demonstrate.

Ian Skellern wearing a slim Urwerk UR-103.03

There is however one very major flaw with this watch; I have to give it back!

“Better to have loved and lost . . . .” I tell myself. Without much conviction.

Thank you very much, Felix, for trusting me with your baby. It has truly been my pleasure.

For more information, please visit www.urwerk.com/en.

Quick Facts Urwerk 103.03

Case: 50 (including lugs) x 36 x 13.5 mm, white gold

Movement: manual winding Caliber UR-3.03, 3 Hz / 21,600 vph, hour satellites in grade 2 titanium with black PVD coating, orbital cross in grade 2 titanium

Functions (front): wandering hours on cone-shaped satellites indicating minutes

Functions (back): Control Board, 15-minute dial, seconds dial, 43-hour power reserve indicator, fine-tuning screw (adjustment +/- 30 seconds per day)

Price: $30,000 – $40,000 on the secondary market, depending on model and condition

* This article was first published on ThePuristS in 2005 and on Quill & Pad on March 19, 2018 at Felix Baumgartner, Urwerk, Harry Winston, And The Opus V: Where On Earth Did That Come From? Plus UR-103.03 User Review.

You may also enjoy:

The Urwerk Opus 5 For Harry Winston That Almost Was

Urwerk UR-220: Spacetime Curves And Satellites Reign Supreme

Urwerk UR-111C: A New Titan Among Titans (Plus Video)

Urwerk Vs. MB&F: How Do They Square Up?

Urwerk And The Gustave Sandoz Clock That Doesn’t Tell The Time

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!