Looking through the latest Phillips watch auction catalogue, I discovered a hidden gem among all the usual rare Rolex and Patek Philippe variations going up for auction on May 8-9, 2021: lot 165.

Phillips Lot 165: Richard Habring’s personal IWC Portugieser Split-Seconds Chronograph prototype Ref. 3712 (photo courtesy Phillips)

Lot 165 is one of the most important prototypes in the history of IWC. A true rarity and a true piece of watch history. It is Richard Habring’s personal split-seconds chronograph prototype. And in case you’re not acquainted with the history of the groundbreaking IWC split-seconds chronograph, this is worth revisiting.

Richard Habring and the creation of the IWC split-seconds chronograph

In the fall of 1990, Habring began working at IWC, which was then a much different company than it is today. He became project leader, responsible for developing a practical, cost-efficient split-seconds chronograph that also had to be as easy to assemble and maintain as possible. The split-seconds chronograph was at that time one of the most difficult complications to master – and it still is, exemplified by the extremely low number of them coming out every year; how many new rattrapantes came out in 2020? One?

Split-seconds chronographs are expensive to develop and expensive to produce. IWC, then not yet under the umbrella of the Richemont group and certainly more value-conscious than most at that time, was only just getting into high complications. These were kicked off in 1985 by IWC’s then head watchmaker Kurt Klaus’ masterful Da Vinci perpetual calendar, a watch that became an industry milestone and an almost instant classic.

A decade later, in 1995, the Da Vinci received a pinch of Habring’s genius as well: the addition of a new tenth hand in honor of the model’s tenth anniversary displaying the rattrapante function.

The rattrapante, as it’s known in French, is a synonym for split-seconds chronograph. In German it is Doppelchronograph, “double chronograph,” the literal word for this complication that enables two short time periods to be measured simultaneously.

IWC was not a full manufacture at that time, and it was a no-brainer to continue using the tried-and-tested Valjoux 7750 chronograph movement as the base, just as it had been the base of all IWC’s high complications to that point.

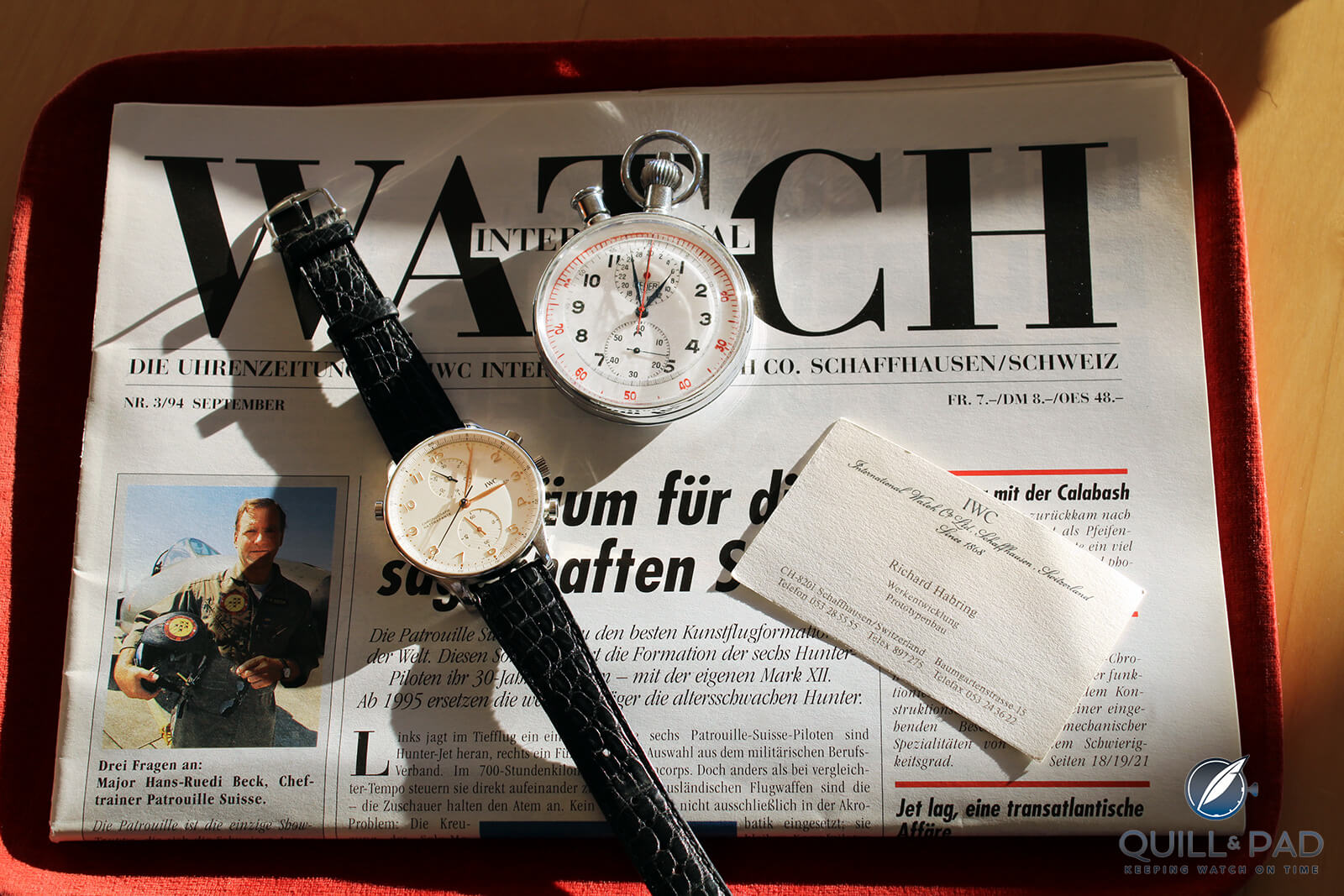

Phillips Lot 165: Richard Habring’s personal IWC Portugieser Split-Seconds Chronograph prototype Ref. 3712 along with the Heuer stopwatch and disassembled Valjoux 9 caliber that it comes with (photo courtesy Phillips)

To keep the watch as thin as possible, Habring, also the prototypist, removed the date, chronograph hour counter, and automatic winding system, transforming it into a hand-wound movement.

Habring developed his split-seconds mechanism to fit onto the 7750, but made another enormous change to the base workhorse: inspired by the study of a Heuer pocket watch with split seconds powered by Valjoux Caliber 9, he did away with the column wheel to further reduce the movement’s thickness, turning it into a more space-efficient, cam-controlled chronograph.

The base 7750 movement was readily available in those days and its parts were easy to machine, maintain, and repair. Habring expounded on its philosophy by engineering what is usually a very tricky mechanism to be relatively affordable and a lot more reliable. The split-seconds mechanism can be much more fragile in other configurations.

Patent DE000004209580C2 was filed in 1992, the core of which was the first use of a cam to operate a split-second chronograph function instead of a column wheel, which, as Habring told me, “IWC did not have the abilities to produce in-house as [then IWC CEO] Günter Blümlein had basically intended for this new movement.”

Only two years after he had begun working at IWC, in 1992 Habring’s split-seconds chronograph was ready to be added to IWC’s Pilot’s Watch collection to become the legendary Doppelchronograph (“double chronograph”). The large 42 x 17 mm case came complete with a third chronograph pusher for the extra chronograph measurement. In every sense, it fit the ethos of that era’s IWC.

IWC Pilot’s Watch Doppelchronograph Reference 371101 from 1992

As IWC itself says, this watch kicked off “the age of modern pilot’s watches,” which “began in Schaffhausen in 1992 . . . the Pilot’s Watch Double Chronograph (Reference IW3711) established IWC as an expert in creating robust, precise chronographs . . .”

The base 7750 movement with Habring’s cam-controlled split-seconds chronograph addition became known as IWC Caliber 76540 (and real fans might also know that internally IWC calls the 7750 Caliber “7920” – named so for the movement height of 7.9 mm).

Quickly thereafter, in 1993, the new movement went into what was then the world’s most complicated wristwatch: the IWC Il Destriero Scafusia featuring a perpetual calendar, minute repeater, tourbillon, and split-seconds chronograph – launched not uncoincidentally in the year of IWC’s 125th anniversary.

Richard Habring’s IWC Portugieser Split-Seconds Chronograph prototype

When the decision was made to put Habring’s innovative split-seconds chronograph into the brand’s Portugieser model, he first created a prototype. Habring used steel parts from Il Destriero Scafusia and applied a higher-grade finish to a nickel-plated movement with Geneva waves on the top bridge and balance cock. In order to admire the movement, and in keeping with what had become a trend by then, and he also added a display back.

Phillips Lot 165: back of Richard Habring’s personal IWC Portugieser Split-Seconds Chronograph prototype (photo courtesy Phillips)

These modifications did not make it into the final production pieces introduced in 1994, and Habring’s prototype remained unique. He wore it as his everyday watch until he left IWC in the early 2000s to partner with his wife Maria, also a watchmaker, to create the boutique brand Habring2, based in one of the most idyllic parts of Austria.

The IWC patent on this split-seconds chronograph construction expired in 2012, which allowed the Habrings to add it to their own eponymous line in the form of the Doppel-Felix and the Perpetual-Doppel perpetual calendar split-seconds chronograph.

Why part with this piece of history?

Which brings me to perhaps the most burning question that potential buyers might have – and which I know I always have when I see personal pieces like this at auction: why would someone – in this case Richard Habring – part with such a historical timepiece so intertwined in his own personal and professional histories?

So I asked Richard why he decided to sell it, and he replied, “I’m parting with this watch because I would like to close out my personal IWC chapter. My wife Maria and I founded Habring2 17 years ago, and since then our little Austrian manufacture has written its own successful chapter in watch history. With further chapters to follow. IWC is the past for me; Habring2 is my present and my future.”

Phillips Lot 165: Richard Habring’s IWC Portugieser Split-Seconds Chronograph prototype

This piece of history will go to its new owner freshly serviced by Habring2.

Phillips lot 165: personal IWC memorabilia from Richard Habring (photo courtesy Habring2)

The prototype is accompanied by an incredible set of accessories: a Heuer split-seconds pocket watch, a disassembled Valjoux 9 movement, a painting of the Doppelchronograph, a copy of IWC’s in-house newspaper International Watch in German (3/94 from September 1994) with an article on Habring from his time at IWC, Habring’s business card from IWC, a letter from Habring confirming this was his personal watch, and a signed graphic novel about Habring2.

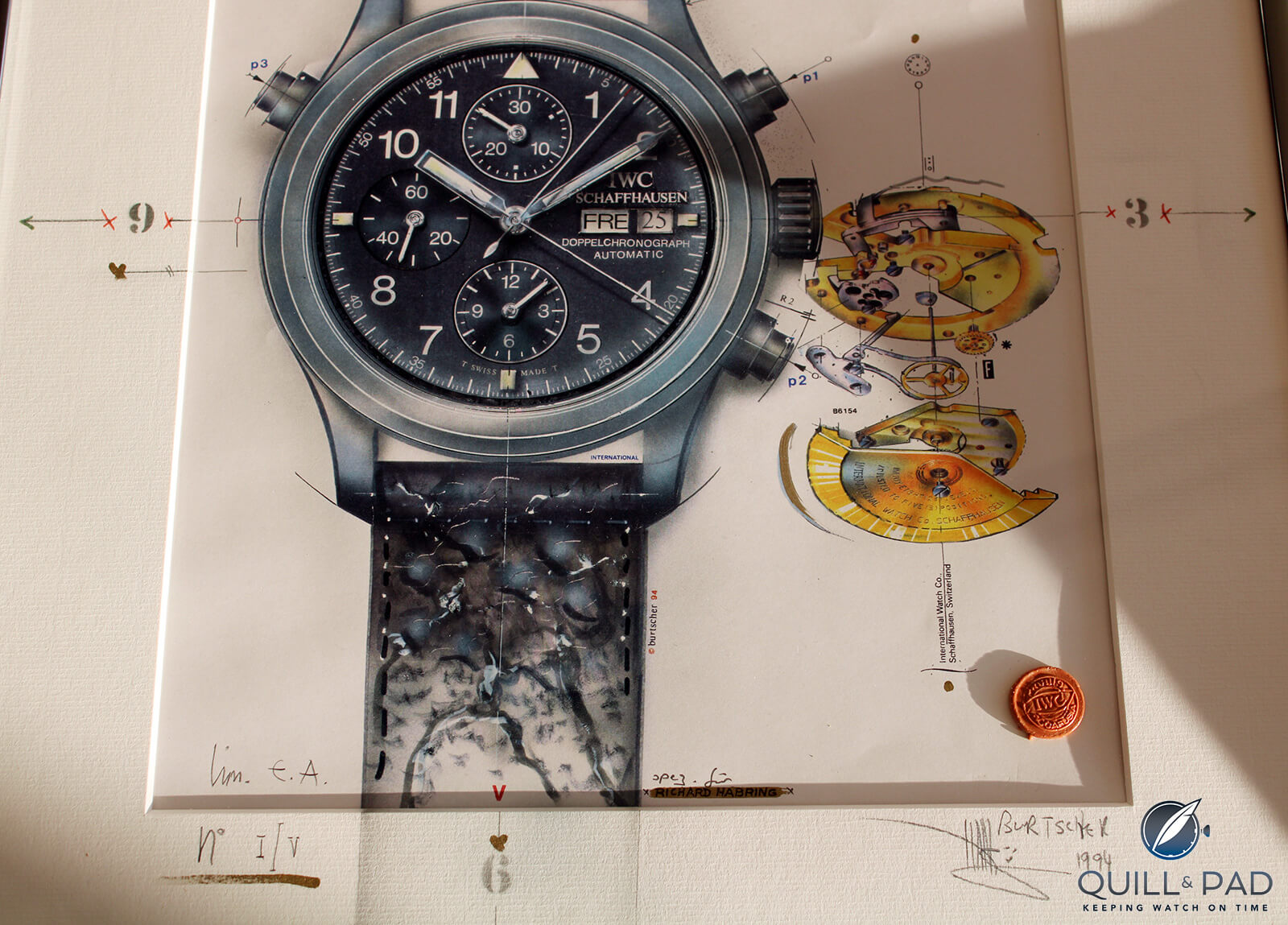

Part of Phillips lot 165: IWC Doppelchronograph painting (photo courtesy Habring2)

This IWC Portugieser Split-Seconds Chronograph Prototype is not only a historically important timepiece: it is proof positive of the gigantic hearts of Maria and Richard Habring as the proceeds of the sale will be going to charity. The largest portion will go to Caritas Austria, a nongovernmental organization helping the poor both locally and abroad, and the rest to support local schools and associations.

Big hearts and certain of their future: Maria and Richard Habring

As befits the Habrings’ own ethos, the Austrian Caritas was selected as the main beneficiary of the proceeds of this piece of history for its local and impartial qualities. “The donation will be given for the benefit of poverty-stricken people in Carinthia and to help refugees in the Balkans and Greece,” Maria Habring explained.

Maria and Richard Habring – the watch industry’s own “double trouble watch couple” – live in the here and now, and share their good fortune by helping to make a better future for others.

For more information, please visit www.phillips.com/detail/iwc/CH080121/165.

Quick Facts Phillips Lot 165 IWC Portugieser Split-Seconds Chronograph Prototype Ref. 3712 by Richard Habring

Case: 42 mm, stainless steel

Movement: manually wound Caliber 76240 (ETA Valjoux 7750 base) with added rattrapante, 28,800 vph/4 Hz frequency

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; split-seconds chronograph

Year of manufacture: approx. 1995

Estimated auction price: €7,300-€14,500/CHF 8,000-CHF 16,000, no reserve

You may also enjoy:

Valjoux 7750: The World’s Greatest Chronograph Movement By Far (By Popularity And Numbers)

Habring2 Jumping Second: Great Looking And (Relatively) Affordable Haute Horlogerie

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Bit of a bargain, everything considered.

No kidding! I am very curious to see what this watch goes for – and hope it goes for a lot!

Your wish came true – sold for just shy of CHF 120k! Well deserved.