by Ryan Schmidt

Why watches? What is it about a watch that captivates us?

Ask what makes a watch enthusiast tick, and the idea of the “soul” of a watch might well feature in the response – the idea that something elevates the watch from a cold object of engineering to something of greater import; the idea that there is some essential nature in a watch connecting with us on a deep and inarticulated human level.

As enthusiasts we carry accumulated experiences of this connection. It’s something that is at once both deeply personal and a joy to be shared. The connection drives us to consume vast amounts of time and money, and it ignites a passion in us that emboldens us with strong opinions and even to fierce debate at times.

Some of us struggle to define our loyalties: where they crystalize and where they drop off.

We can’t put our finger on it, but the soul is there. We just know it.

Longines Heritage Avigation over ‘Day and the Dawnstar’ by Herbert James Draper (image courtesy @thehealer74)

Mechanical versus quartz

Some settle on the binary position that the mechanical watch is superior to a battery-powered, quartz-regulated one. The mechanical watch has the soul; it has more integrity, honesty, and human quality than a quartz watch. But when we probe a little deeper we are confronted with the kinds of underlying contradictions that bubble under the surface of any form of fanaticism.

For some, that’s fine; there is enough comfort in knowing exactly what they like and what they don’t like. It’s controllable and reliable. With enough effort, they can structure enough objective support for their position and there ends the journey.

But for others, enthusiasm is an infinite path of discovery and rediscovery. This path can only be traveled when we let go of the need to know today what lies around the corner tomorrow. If this is you, perhaps you might like to join me on a special journey: to the soul of the watch.

F.P. Journe Octa Calendrier over ‘The Mirror’ by Frank Dicksee (image courtesy @thehealer74)

Is there “soul” in the kinetics of the escapement?

Is the soul of the watch in its beating heart?

The primary function of a balance wheel might be to regulate the movement, but with its hypnotic dance we attribute a more personal, human aesthetic to it. Each oscillation animates the movement, bringing the watch to life from a metallic slumber.

We know it’s the result of calculated mechanics, but there is a warmth to experiencing it. It’s similar to birdsong or the bioluminescence of a jellyfish, which are bewitching to observe despite our knowledge that they exist for some essential and utilitarian function. It seems to be our nature to celebrate and even to anthropomorphize such phenomena, and this is certainly the case with a mechanical escapement.

Whether it is the simplest Swiss lever escapement or a 60-second flying tourbillon, our connection with the mechanical watch is often forged right here, in the beating heart of a watch, the regulator.

The swing of the balance wheel, the throb of the hairspring, the twitching of the lever, and the rapid stop/start rotation of the escape wheel; it’s impossibly fast and inescapably impressive.

There is little more enchanting than the dance of a mechanical escapement.

The dance goes uninterrupted in total autonomy for days, even weeks.

Even when the watch is on the wrist and the kinetics of the escapement are concealed the rapid sound of impulses can be heard, even felt, through the walls of the case and the crystal; a tiny tick with every vibration, eight per second in most cases. Unseen, time passes beneath the dial like a winter stream rushing below its frozen surface.

Vacheron Constantin Harmony Complete Calendar in pink gold over ‘The Assualt’ by William Bouguereau (image courtesy @thehealer74)

Is there “soul” in the kinetics of the automatic winding rotor?

The animation of a watch is not limited to its escapement. If your mechanical watch is automatic and features a sapphire crystal case back, you will be able to enjoy another visual treat: the oscillations of the rotor as it winds the mainspring.

This often gloriously decorated chunk of precious metal will dance with you. One moment it’s sedentary, the next it’s caught in a whirlwind of its own momentum inspired by yours. Then you have the second hand, each impulse exaggerated by a circumnavigation that is both juddering and smooth.

The action of a hand making six to eight stops per second takes place in the deep twilight of what is visually perceivable, but between the right and left side of the brain we experience something that both makes perfect sense and delights.

Simply put, movement is life, and mechanical movement brings life to the watch. This is the animation that forges a personal connection. However, this doesn’t explain the allure of the two-handed watch, of the deadbeat second, or the sealed case back.

There are indeed watches that dampen the kinetic spectacle of the watch, yet we retain our connection. Is it because we have been conditioned to visualize what we know is going on under the dial or is there something broader forging the connection?

Certainly there are watches that dangle kinetics in front of us like a cheap trick and it leaves us cold. There are few elements of a watch that draw louder objections from an enthusiast than a superficial rotor that does not wind the mainspring or a second escapement that adds nothing to the first.

Maybe it’s not the actual kinetic movement, but how that movement is enabled, the form, and purpose of that movement?

Vacheron Constantin Historiques American in platinum over ‘Seduction’ by William Bouguereau (image courtesy @thehealer74)

Is there “soul” in the earthly mechanics?

The kinetics on a dial deliver the first impression of a watch, but there are conditions attached to them. When observed on the wrist of a new acquaintance, many enthusiasts will suspend their appreciation of a watch (indeed, perhaps even its wearer) until the sweeping second hand confirms to them that the movement is mechanical.

The watch may look very promising, but we hold back on our emotional attachment until we know that the feeling is mutual. The juddering second hand sweep is something of a Pavlovian bell that waters the mouth of an enthusiast. But it’s just the bell; where lies the food?

Fantasy watch inspired by early 2000s limited edition Audemars Piguet and A. Lange & Söhne models over ‘Lucifer’ by Franz von Stuck (image courtesy @thehealer74)

Do quartz watches have “soul”?

This brings us to one of the most common standpoints in watch enthusiasm: that mechanical watches have a soul and quartz-regulated examples do not.

There is something undeniably brilliant about a device made from earthly materials harnessing the power of a spring and self-regulating its release in order to document the passing of time to an accuracy of just a few seconds per day.

That it does this within a diameter of a few dozen millimeters is astounding. This is human micro engineering at its best, and there is something entirely and palpably human about the wheel, the spring, and the documented second. The shared DNA of this phenomenon is evident in countless everyday machines and experiences, from the combustion engine to the dog leash.

Hold this up against a quartz-regulated movement and it’s perhaps easy to choose sides. What happens on an integrated circuit board between two quartz tines is simply too fast and too small to observe or to relate to.

This is not mechanics; this is electronics.

Add a few more circuits and you have yourself an artificial intelligence capable of enslaving the human race. Naturally, when AI takes over, it will be good old-fashioned analog mechanics that will enable mankind to regain control. In the wheel and spring we trust.

Surely the soul of the watch is simply in its mechanics and visible engineering?

Perhaps, but most quartz watches are also somewhat mechanical. Unless you have an LCD digital quartz watch, the movement is likely to employ wheels and gear ratios to deliver the different rates of rotation to the hands on the dial. Some quartz-regulated watches have mechanical power sources, mechanical complications, even electro-mechanical escapements.

There are quartz-regulated watches offering nearly every element of horological mechanics, but it’s the addition of that electronic regulator – or the absence of a mechanical escapement – that draws sighs of disapproval from many enthusiasts.

Perhaps it is critical to know that the mechanics are more earthly, and there is nothing post-industrial assisting the process?

Then what about the fact that many mechanical movements in existence are made by robots and from materials making quartz crystal seem entirely down to earth by comparison? Beryllium, rhodium, corundum, Nivarox, silicon – some of these materials are rare, some exotic, and some are even deadly when consumed.

Horology may have started with the basics, but today’s movements have plundered the periodic table in search of materials that defy the most basic earthly laws. There is nothing grounded or simple about them. Take bearing jewels as an example; early watches employed natural jewels such as rubies or diamonds. Today’s jewels are made from synthetic ruby (corundum). It’s not unlike a synthetic diamond, but whereas the market has been very slow to adopt synthetics in jewelry, they are completely accepted in watchmaking.

Not convinced? If your dislike of quartz has built a wall around your opinion, I urge you to consider peering over it.

Patek Philippe Gondolo Reference 5098R in pink gold over ‘Blue Bird’ by Sergey Solomko (image courtesy @thehealer74)

The case for quartz

A quartz watch is lifeless, they say.

There is nothing to be seen here but the robotic precision of a single tick per second. Everything else happens on a level that is faster and smaller than anything we can enjoyably experience.

Surely the soul of a watch cannot be found here?

But there is hope for quartz. As mentioned earlier, not every quartz-regulated movement is just a circuit board sandwiched between a small battery and a smooth-ticking zombie second hand. There is more to be appreciated in that simple setup than it seems today.

Let’s start with quartz itself. This is a naturally occurring mineral comprising silicon and oxygen; in fact it’s one of the most common minerals on earth. Seiko, a thoroughly established master of quartz, has a facility for growing its own crystals in-house. These are simple, beautiful crystals, deserving of human connection.

These crystals also possess a gift: piezoelectricity. When placed under mechanical stress such as twisting or vibrations, a quartz crystal generates electricity. And the process is inverted, passing electricity through quartz makes it vibrate, and it vibrates very constantly at a very specific high frequency that’s 10,000 times faster than a typical mechanical balance.

A quartz escapement is as every bit as magical as it is incredibly reliable. Electronics are the key to unlocking the kind of accuracy in timekeeping that a mechanical movement will never compete with. The resonating frequency of quartz is so uniform that it can be relied upon to regulate a watch in terms of seconds per month, rather than per day.

How can the piezoelectric magic of quartz be dismissed so readily against the elastic properties of a hairspring? We forgive the latter for being machine milled, laser/ion etched, and made from almost the same material. The former is judged harshly for receiving electric rather than mechanical impulses and for performing its task with near perfect and imperceptible excellence.

It’s too perfect, too clinical; it’s therefore soulless.

Perhaps that’s not the crux of the issue; perhaps it’s the inferior visual aesthetic. It is indeed harder to love a movement that has a visible microchip, plastic components, and a relatively large battery occupying a space usually reserved for Geneva stripes, jewels, and wheels.

But there are some quartz models so good that their makers have proudly made an art form of them; the Bulova Accutron and the Transparent Swatch, for example, are not without their passionate fans.

There are others who apply fine traditional finishing techniques to the plates that cover the movement or go even further with techniques that rival the criteria of the Geneva Seal and component mechanisms that speak of true engineering.

F.P. Journe Elégante 48 mm in platinum over ‘The Red Cross’ by Evelyn de Morgan (image courtesy @thehealer74)

The spring drive-regulated Credor Eichi II and quartz-regulated F.P. Journe Elégante are just two examples that surely claim more than a handful of ubiquitous mechanical movement scalps.

Perhaps you’re still not convinced; a purist? Well, that’s fine, but there might be some similarities between your beloved mechanical archetypes and these “cyborgs.” And if we triangulate their common allure, we might fall upon the soul of the watch.

Chronoswiss Flying Regulator Jumping Hour over ‘Serenity’ by Edgar Maxence (image courtesy @thehealer74)

Is there “soul” in memories and dreams?

Consider the watch as a vessel within which we place fragments of our past and our future. Certainly, when passed down from a loved one, the watch exists as an echo of a person that we once had a deep connection with. This is perhaps the most potent of human experiences that can imprint itself on a watch of any merit.

But, there are more subtle ways in which the watch can capture our past.

I have several brief but powerful memories that I cannot separate from my enthusiasm for watches: a blue rubber digital Casio on a kitchen counter in 1988 England, a stopwatch in secondary school physics class, a skeletonized tourbillon pulsating in a Parisian boutique window in the autumn of 2006. I recall these moments vividly; they are intoxicating drinks of discovery, wonder, and confusion, with only the precise constant of time holding it all in.

It may be on an unconscious level or as clear as day, but the watches that stop us in our tracks will likely bring forth momentary memories of these experiences. Or if not visual, they might give rise to a feeling that takes us back to that place. The shape of the numerals, a complication that can’t be immediately deciphered, the glow of the lume; they transport us to a room that only we know exists, and in doing so a bond is formed with this particular watch.

Then there are watches that hint at a past that did not occur, but somehow the effect resonates with our combined imagination and sense of the past. This is the realm of steampunk and fantasy, where innovation enables artifacts from the past to be brought to life vividly. Meteorite dials, hydraulic pistons, alternative pasts forging new futures: a cloaked spaceship 15 miles above Geneva with an onboard workshop of Abraham-Louis Breguet clones busily producing the De Bethune portfolio.

A watch is capable of capturing the past and present and merging it with the logical and the whimsical unlike anything else. In this sense, perhaps the soul of the watch is not a specific detail, but comes to exist by a combination of details, collectively compelling us to project an image of our own soul into this inanimate object?

Patek Philippe Reference 5496P in platinum over ‘Vanity’ by Frank Cadogan Cowper (image courtesy @thehealer74)

Is the “soul” in the reflection of its maker and beholder?

What if the thing that connects us to a watch is the array of cues that remind us of who we are and what we are capable of? That’s not to say that watch enthusiasts are like Narcissus, falling in love with their own reflections. This is about theories of collective consciousness, identity, craft, and our relationship with time itself.

What does a fine mechanical watch say to us?

It makes better sense when you consider an imaginary spectrum of horological perfection. Between a stick in the sand and the atomic clock there is a spectrum of accuracy and engineering execution. Someone who knows very little of horology might expect that our enthusiasm would run in a tight positive correlation with this spectrum. But it doesn’t.

In most cases there is rather a high level of enthusiasm for the most rudimentary timepieces. It likely grows as these objects become more complex and refined. But there is a point at which this enthusiasm starts to drop off. We can appreciate the leaps in accuracy and automated production, yet somewhere our passion has been left behind. Where on the spectrum does this take place?

There is an apex that represents the limits of our ability to comprehend and a watchmaker’s ability to execute. When you elevate beyond this point, the watch may objectively improve, but humankind is left behind. Perhaps the soul of a watch is made up of reminders that a lathe has milled this wheel at the command of a human, the dial has been turned or the ink applied by mortal hand?

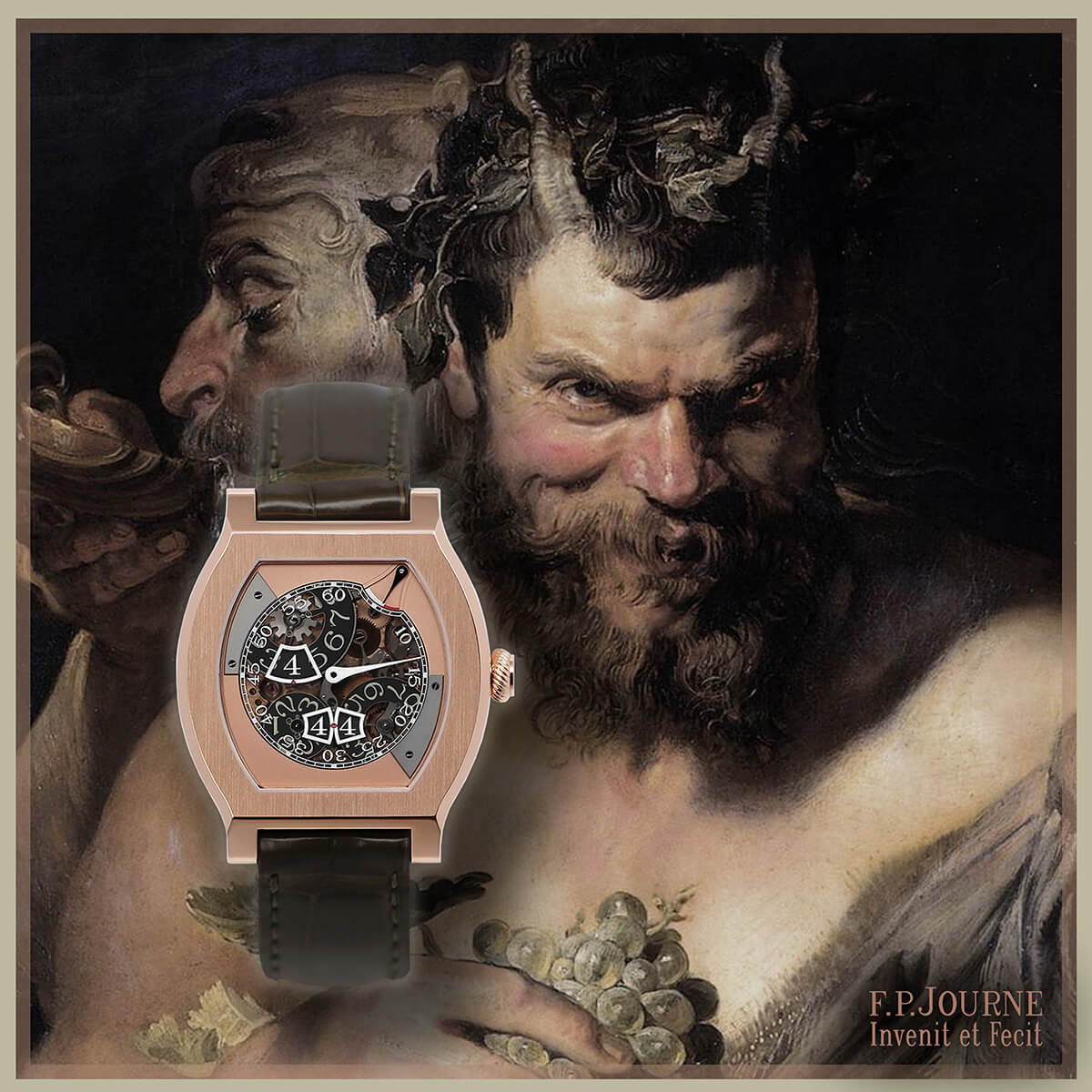

F.P. Journe Vagabondage III in red gold over ‘Two Satyrs’ by Peter Paul Rubens (image courtesy @thehealer74)

You can look at a Philippe Dufour Simplicity, an A. Lange & Söhne Datograph, a Roger Smith Series 2, or a Patek Philippe Reference 5078 Minute Repeater and be forgiven for uttering the words “perfection.” But these are not perfect watches.

To the naked eye, even under a loupe, these appear as perfect timepieces, but they are not.

There are blemishes and microscopic burrs; the movements still endure the slow and terminal effects of friction, still give rise to error. And if the movement beneath the crystal appears to show no signs of visual imperfection, its exterior eventually will.

Think of the human face. While a degree of symmetry is seen to correlate with the perception of beauty, there is a drop-off after which the face is too symmetrical and becomes unrealistic, even unnerving.

In the same way, we heavily scrutinize the application of luminous paint on the dial, striping on a bridge, chamfering on an edge. And once the expected standard is met or exceeded, our mind discounts the miniscule details that separate what we see in front of us from what is truly perfect: perfectly parallel, perfectly curved, perfectly meshed, poised, and polished.

You could say that our mind does not actually discount this information as such; instead it subconsciously seeks it out. It is not looking for a reason to dismiss the watch; it is looking for the reflection of its maker. Each reflection is a thread that binds us. Each forms a component part of the soul of a watch.

And what about its beholder?

Audemars Piguet Royal Oak perpetual calendar over ‘The Doom Fulfilled’ by Edward Burne-Jones (image courtesy @thehealer74)

The golden ratio; the unrelenting passage of time; solutions to a series of problems; the triumph of engineering; readings for the now, the was, and the soon to be; a warm glow or a stark line; the tick and the tock. Everyone can find something to see of themselves in a watch. However, this is where we leave each other. What it says to us and of us is as complex as understanding ourselves and our own souls.

But it’s there. I just know it is.

We were kindly granted permission by @thehealer74 to use his artwork to illustrate this post. All photography used in this artwork, which combines timepieces from his personal collection and historical paintings by nineteenth-century artists, is original. For more of this designer’s soulful and inspiring work, please follow him on Instagram.

* This article was first published on August 25, 2017 at What Makes Up The Soul Of A Watch: A Contemplation (And You Will Not Want To Miss The Imagery!)

You may also enjoy:

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

“Consider the watch as a vessel within which we place fragments of our past and our future”

It is a peculiar phrase worth pondering !