by Ashton Tracy

Since the dawn of time (well, almost) watch brands have charmed us with the allure of precious jewels in their movements.

At one time this went further than just advertising their inclusion in an accompanying booklet. Some manufacturers ventured as far as printing the number of jewels in the movement on the dial, a conceit that that has thankfully practically disappeared.

Vintage Jaeger “Panda dial 4 ATM”: proudly professing it has 17 jewels in the movement

Seriously, who cares how many jewels their watch has?

You’d be surprised.

Having spoken to watchmakers with many more years at the bench than myself, I came to realize that the confusion around jewels in decades past was a hotly debated topic. I’ve even been recounted tales of customers accusing watchmakers of stealing the jewels from their watch to fund their lavish lifestyles!

My personal favorite is the story about the customers who sternly informed their watchmakers they would be counting the jewels once the watch was returned from repair. A friendly warning, just in case they were thinking about pocketing them.

While some customers may have believed their watches made use of precious stones that in some way contributed to the value of the watch, the reality is that watch jewels are (practically) economically worthless.

So what is the truth about the jewels and why do they matter so much?

The answer (as so often) is friction.

Friction is the enemy of the watch movement as watches are required to work on a scale that most of us can not even comprehend.

Rolex’s Parachrom balance endstone shock protection in Caliber 3135: of course a ruby jewel

When manufacturing pivots for train wheels and balance staffs, tolerances are generally 5 microns either side of the actual number. Five microns is equal to 0.005 of one millimeter. Yes, of one millimeter.

So reducing friction is necessary to ensure top performance for a watch movement. And this is done by setting such watch components in bearing jewels instead of having metal rub metal.

“Boules”

The jewels that we use in watches today and decades past are synthetic, the most common being synthetic ruby. These jewels are grown in a controlled environment as something called a boule, the French word for a cone-shaped chunk of the material.

The ruby jewels must then be milled, sawed, and polished into the desired shapes, which is time-consuming and difficult, necessitating the use of diamond-tipped tools.

Where the natural rubies would have impurities called inclusions that made them difficult to work with as a bearing jewel, when grown in a laboratory setting inclusions do not occur: the grain in the jewel is minimal and they can be polished to a very high standard.

On the Mohs scale of hardness both synthetic and natural rubies rate at 9. Diamond is the hardest material on the Mohs scale, coming in at a rating of 10, making synthetic rubies a logical, cost-effective choice as a bearing jewel.

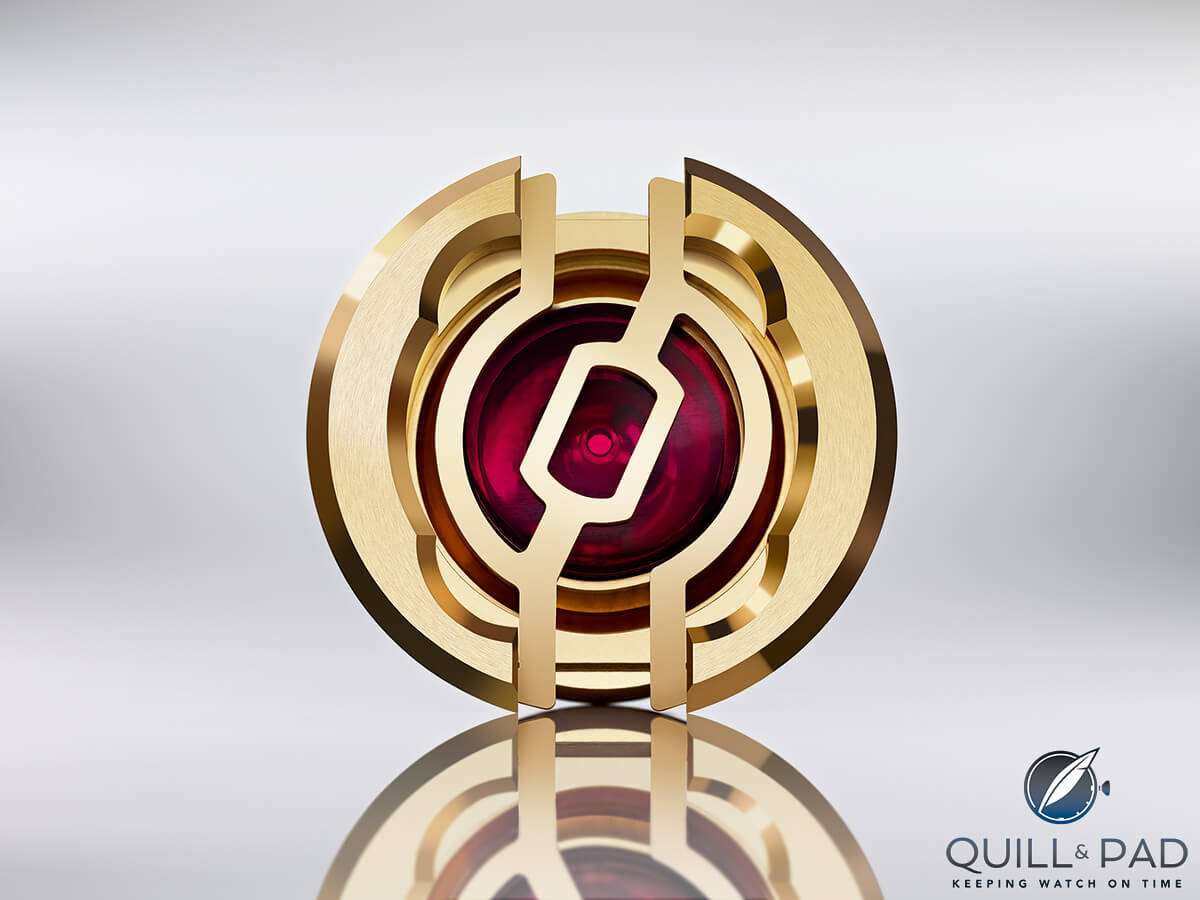

Synthetic ruby bearing jewels set in gold chatons in the movement of Raúl Pagès’ Soberly Onyx

Modern watch jewels

Jewels today are friction-fit into main plates and bridges, however that process only began around the 1930s.

Before then jewels were “rubbed in” to a brass setting. The great disadvantage with this style of jewel setting is the time and effort needed to replace them.

Modern friction fit jewels are just pressed in and out with ease, but with a rubbed-in jewel great care and time must be taken to burnish the new setting.

Contemporary watches utilize jewels in a variety of areas, including as pivot bearings for wheels, automatic winding components, and calendar mechanism as well as pallet stones.

The gear train wheels of a watch are the means of transmitting power from the mainspring to the escapement. In order to make that process as efficient and friction free as possible, jewels are used as bearings for the pivots of those wheels. Steel or brass bearings would cause excessive friction, thus consuming unnecessary power from the mainspring.

The use of jewels in combination with the highly polished steel of the pivots drastically reduces that friction.

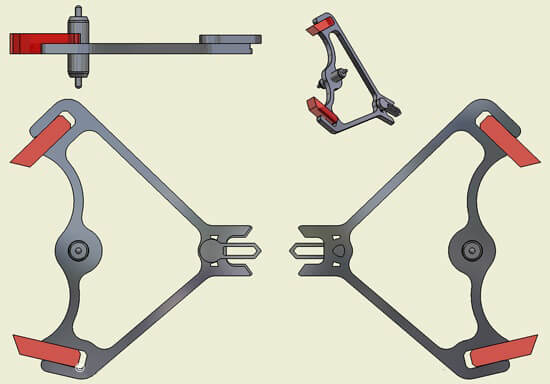

Romain Gauthier’s triangular anchor with ruby pallet stones

The same is true for the escapement lever’s pallet stones, which work against the highly polished steel surface of the escape wheel teeth and reduce the friction experienced there.

Balance pivots use jeweled bearings, though their setup is slightly different: they utilize a standard-style train wheel jewel bearing except that it has metal seating around it. That metal seating holds another jewel in place that is positioned on top of the balance pivot, keeping the lubrication for the jewel in place but also greatly reducing friction.

Watches of a higher quality, such as those receiving C.O.S.C certification (or higher) are manufactured to a higher level of precision. One area this particular aspect stands out is the spring barrel.

Traditionally, barrels would have brass bushings as bearings for their arbors on the main plate and barrel bridge. However, a watch manufactured to a higher tolerance would swap those out for jeweled bearings.

Assembling a patented ruby link constant force chain for Romain Gauthier’s Logical One

Other areas in which movements utilize jewels is the calendar work. In examples such as Rolex’s calibers, the jewel is used to reduce the friction when a lever actuates against a steel cam to ensure the watch changes exactly at midnight. The jewel is mounted on the lever, thus reducing friction with the result being a smooth, precise date change.

Ruby jewels are also used for the roller jewel. The roller is positioned on the underside of the balance wheel and has an impulse jewel, which swings back and forth in an arc, engaging with the pallet to allow the release of energy. The jewel for the roller is combined with highly polished steel of the pallet fork to again reduce as much friction as possible so the watch will run at peak performance.

The automatic rotor also is an area where friction consumes power, which causes the watch to not wind as efficiently as possible. In some movements, ball bearings are used to increase the winding efficiency, but in calibers that use an axle, jewels are employed.

The axle is generally seated against two jewels that are fitted into the upper and lower bridges of the automatic work.

Movement detail of the Vacheron Constantin Malte Squelette showing automatic winding system elements and an attractive selection of ruby bearing jewels

Jewels can also be used in countless other areas of more complicated watches such as chronographs, minute repeaters, and countdown timers.

Unfortunately, your synthetic rubies won’t be funding your next trip around the world trip, but they do play a vital role in the accuracy of your watch, making these little gems truly precious.

* This article was first published June 29, 2018 at The Number Of Jewels In A Watch Movement Indicates Value, Doesn’t It? A Myth Debunked.

You might also enjoy:

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Looks like this article been re-run more time than episodes of ‘Friends’. Nonetheless, very interesting and informative on the subject. I’ve been collecting for a number of years but still enjoyed. Thanks!!

Excellent show and tell.

I remember reading a story a while back that stated there was a period of time when 30-40 jewels became a bit of a trend because companies realized consumers thought more jewels was better.

That reminded me of a story about competing hamburger chains. One chain was offering a 1/3 pound burger to try and attract some business from the king of 1/4 pounders. That concept flopped because people saw 1/4 as being bigger than 1/3. D’oh!

Did the burger thing blow your mind or confirm what you already thought ? It did both for me.

Love the Jaeger , for sale ?

We do not sell watches, but thank you for asking.

Se os olvidó hablar de las joyas decorativas visibles en las ventanas traseras y en el frontal del reloj. Esas si pueden financiar su viaje

I fondly remember the Wimpy half-pounder burger. 😊

They were rejected by The British Public because they were British, which is just as stupid as confusing fractions.

No offense, but I, as a specialist, was quite surprised by the mention of such an ancient scale for measuring the hardness of materials as the scale of the “Reverend” Mohs. 🙂

Most watchmakers have long preferred to use the much more versatile Vickers scale to describe the hardness of materials used in watches. 😉

While this is definitely true for metals, in the watch world the Mohs scale is more often than not to provide a comparison between (synthetic) sapphire crystal and diamonds. It’s slightly easier to understand quickly.

But this is a certain hoax – the “superhardness” of sapphire. 😉After all, the difference between “9” and “10” is super negligible. But according to Vickers – between “2200-2500” and “10,000” is quite realistic from a technical point of view. And he suggests that sapphire glasses are not a panacea, but simply the best possible. But, careful handling of them will also not be superfluous. 🙂

By the way, dear Elizabeth, not so long ago (six months later than yours) my article on a similar topic was published. 😉

https://deka.ua/articles/dlya-chego-nuzhny-kamni-v-chasakh/48/

I have a watch written CALLIMA 1802/03,,,1959G, made in Switzerland, seventeen jewels, why can’t I find any information about the year of production, etc.