by Ken Gargett

“Champagne Charlie” means different things to different people. For some, it is a person who is a bit of a show pony and who lives life large. Others may think back to the 1944 movie (and possibly even the nineteenth-century song). Some may go as far as the man for whom the sobriquet was created (and we’ll get to him). And some of us may turn to that incredible champagne once created by the house of Charles Heidsieck in a run of five vintages: 1979, 1981, 1982, 1983, and 1985.

Champagne Charlie

It has long been rumored that Charles Heidsieck was planning to revive this label. Certainly, champagne lovers have long encouraged the house to do so. Such would be the likely support it seemed crazy not to.

It was, inevitably, a question I would put to Cyril Brun, Charles Heidsieck’s chef de cave since 2016, or Stephen Leroux, the house’s very popular executive director, every time they set foot on our shores or on the rarer occasions when I got to visit them (no doubt, I was not alone in doing that). And inevitably they would smile and suggest that all things were possible.

Cyril Brun, chef de cave at Charles Heidsieck

Finally, news filtered through that Charles Heidsieck had not only made Champagne Charlie again, but it was being released. Naturally, it was not that simple.

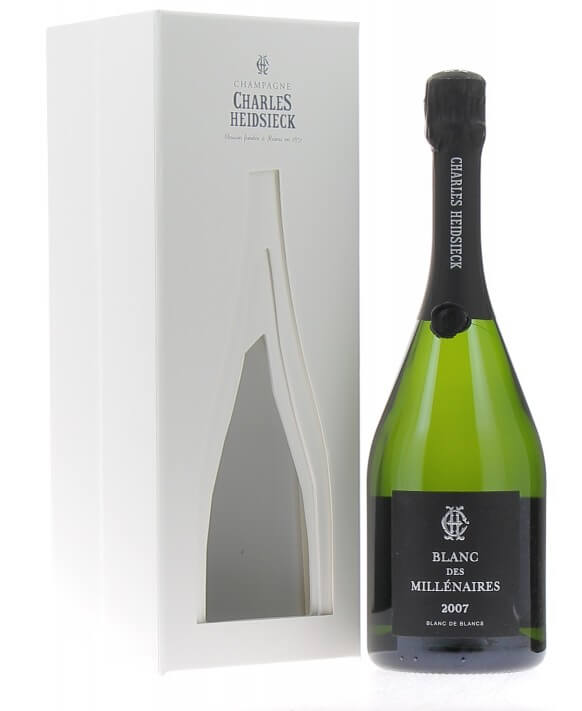

I have looked at the house of Charles Heidsieck previously, writing not only about those amazing earlier Champagne Charlies but the prestige cuvee that replaced it: the wonderful Blanc des Millénaires.

Charles Heidsieck Blanc des Millénaires 2007

Who was Champagne Charlie?

Charles Camille Heidsieck was born in 1822. He was the nephew of Florens-Louis Heidsieck, who founded Piper-Heidsieck, while his cousins established Heidsieck Monopole. Champagne is very much a family affair as he married Amelie Henriot from yet another famous house, Henriot.

In 1851, he founded the third and youngest of the Heidsieck houses. The three have been intertwined over the years in various complex ways. Charles Heidsieck is generally considered the star of the trio, but each has had periods of glory. Ostentatiousness ran in the family as Charles’ father, Charles-Henri, was famous for riding into Moscow on a white stallion in 1811 in advance of Napoleon with both champagne and an order book – he was happy to take orders from whichever side proved victorious.

It was in the United States where Charles garnered most of his fame and his catchy nickname as a regular at the very best social gatherings. He was selling serious quantities of his champagne, but it was not all plain sailing. During the American Civil War, Charles was imprisoned as a suspected French spy.

This came about as one of his American partners had dudded him. In need of funds, Charles headed to the south in secrecy seeking to recover other unpaid debts. This time he at least managed to recover something, being paid in cotton, which he attempted to smuggle back to Europe, an activity that was frowned on by the locals as cotton in the time of war had important uses. He split his bounty across two ships to minimize the risk, should one be discovered. Unfortunately for Charles, both ships were sunk.

Charles then attempted to get himself back home and was given a diplomatic pouch to help facilitate this by the French consul. Bad went to worse as the French consul had slipped some documentation about Confederate business and orders for supplies into the pouch. Charles found himself in prison, not Europe. After seven months, he finally returned to Europe after Napoleon III petitioned Abraham Lincoln for his release. He arrived penniless.

A few years later, his fortunes turned. The brother of one of the debtors who had avoided payment contacted Charles and sent him deeds to land as an apology. The lands turned out to be around a third of the small town that was Denver in its early days. Sales of the land covered all his debts and allowed him to re-establish his champagne house.

Charles Heidsieck today

In more recent times, the man who set Charles Heidsieck on its current road to greatness was the extremely talented Daniel Thibault. Thibault joined Charles Heidsieck in the mid-1970s at the age of just 29 (coincidentally, as I have mentioned previously, the same age as the original Charles Heidsieck when he founded the house).

Tragically, Thibault passed away in 2002 at just 55 but had made a major impact. He had introduced, and subsequently moved on from, that extraordinary range of champagnes, Champagne Charlie, and also introduced the wonderful Blanc des Millénaires. He made, among other great champagnes, the legendary 1995 (of which, executive director Stephen Leroux confessed, they had made some 40,000 cases – a brilliant move by Thibaut).

Stephen Leroux, executive director of Charles Heidsieck

It is probably highly unfair to suggest that Thibault had anything to do with the decision to stop making Champagne Charlie. It was far more likely to have been the hand of the then new owners, Rémy Cointreau (the house was subsequently sold on to Christopher Descours’ luxury goods group EPI in 2011). Rémy Cointreau also owned Krug at the time and the thinking was that other champagnes had to be shoehorned into less exalted niches. There were also suggestions that there was simply not enough topflight material for two prestige cuvees, but the fact that Blanc des Millénaires and Champagne Charlie overlapped for two vintages – 1983 and 1985 – surely disproves this.

Some wondered why the house made the move from a prestige cuvee that was often Pinot Noir dominant to a blanc des blancs, however the house has a close history with the style. It can claim the first ever blanc des blancs when it released its 1906, also the first of the style to be served on a 707 flight (which may or might not make one more inclined to buy a bottle, but they’d like you to know it).

Daniel Thibaut was not the only individual to advance the cause. At a more managerial level around the turn of the century, the decision was made to hold off production of vintage champagnes for several years to build reserve material – so we missed potential stars like 2002, but it paid off with the development of the non-vintage, now considered one of the very best.

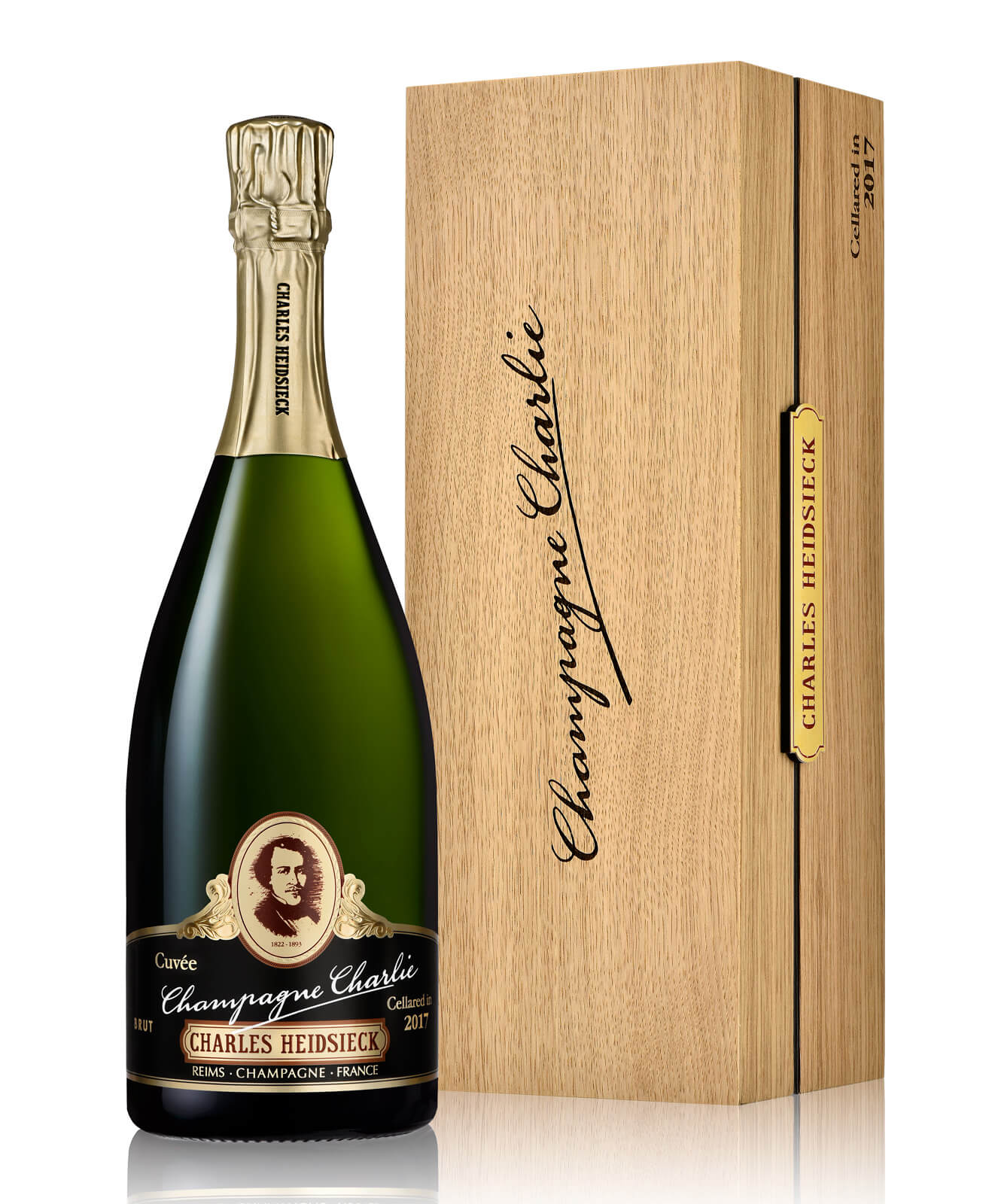

Champagne Charlie re-released

Returning to Champagne Charlie and its most welcome resurrection, as mentioned, only five vintages were ever made: 1979, 1981, 1982, 1983, and 1985. All reasonable to stellar vintages.

Nineteen eighty-one was not widely declared and may raise some eyebrows, but those few houses who did make one had a long-lived wine on their hands. Nineteen seventy-nine was a generous, attractive year, as was 1983. The stars were undoubtedly 1982 and 1985, but they were very different years. Nineteen eighty-two produced a very large crop of classic wines with magnificent Chardonnay. Nineteen eighty-five was a tiny vintage handicapped by extreme cold, but the wines were of sensational quality, this time with Pinot Noir the star.

Some of these wines pop up today as small quantities were included in the Oenothèque program (extended time on lees for even greater complexity) run by the house. Originals are much rarer. Current chef de cave Cyril Brun has described Champagne Charlie as “a wild animal, aiming to encapsulate something unique. Sometimes it contained more Chardonnay or more Pinot Noir, sometimes very different components, but it was always the product of the intuition of the chef de cave.”

Like most champagne lovers, I have been waiting for the reintroduction of Champagne Charlie and could not have been more excited when it was announced. Naturally, there was a twist. Perhaps two or three.

Stephen Leroux was in Australia for the release of this new wine and a few more. It seemed appropriate timing, given that this year is the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Heidsieck.

The big surprise was that Champagne Charlie is no longer a vintage wine but has been released as a non-vintage (multi-vintage is such a better way to describe these wines, but most recognize the term non-vintage). It is rare for prestige cuvees to be non-vintage though certainly not unknown, but I cannot think of one that swapped from one to the other. Laurent Perrier’s Grand Siècle is traditionally a multi-vintage (a blend of three vintages each release), but for a while, and for the American market, that house also released a vintage. Otherwise, none spring to mind.

Why would Charles Heidsieck do this? The cynic might immediately think that it was to gain publicity, but the wine’s reintroduction will do more than enough of that. Leroux then came up with an eye-popping reason: apparently, not all of the original Champagne Charlie releases were 100 percent vintage wines. Today, that might bring the authorities running from everywhere, but back then things were a little more lax (nowhere was that more so than here in Australia, so it would be a touch disingenuous for any finger pointing from this quarter). Leroux was able to confirm that the 1982 was 100 percent from that vintage but most had around 10 percent reserve material, the 1985 a little more. Hence, the reasoning for the move to multi-vintage.

This first release is around 80 percent reserve material – extremely high and a major factor in contributing to the wine’s complexity. The base 20 percent is from 2016 (mostly Pinot Noir from Aÿ) and the reserve wines involved go back into the mid-1990s. More than 30 percent of the wine is reserve material older than 15 years. The split is 52 percent Chardonnay, 44 percent Pinot Noir, and 4 percent Meunier (although other reports suggest 48 percent Pinot Noir and no Meunier). Around 700 six-packs were made, so if you want any move quickly. The price is AUD$900 per bottle.

Despite the wine’s obvious class, the base year is a slightly curious choice for me. Two thousand sixteen is very far from the most thrilling vintage of this era. Surely using vintages like 2008, 2012, 2013, and even waiting for 2018, ’19, or ’20 would have been the wiser decision? Two thousand sixteen was Cyril Brun’s first vintage with Charles Heidsieck, so perhaps he has a soft spot for it. And it is impossible to argue with the result, so they have certainly been vindicated.

Charles Heidsieck Champagne Charlie: tasting notes

Before we get into the tasting, one tiny issue. I have previously discussed my dislike for the mis en cave program run by the house some years ago. In a perfect world, a great idea – putting the year in which the non-vintage wines are laid down in the cellars on the label – and one we are seeing variations of with houses like Krug and others numbering their multi-vintages.

Charles Heidsieck Champagne Charlie

But they should have done it in much smaller font and on the back label from the start. It was very obvious that a great many consumers, sommeliers, and even restaurant managers simply did not understand the concept, assuming the wine was a vintage. As someone who does a lot of wine list judging, I couldn’t tell you the number of times these wines appeared in the vintage sections (we see it today with the champagnes of Ulysse Collin – Olivier Collin makes mention of the base year of his wines on the back label, in very small font, and yet we still have plenty of today’s sommeliers making the mistake of thinking his champagnes are vintage).

It was a system I hated as, deliberately or not, it was misleading. One assumed it had died a natural death, but it has been revived here. Fortunately, it is nowhere near as obvious on the label and given that only a few thousand bottles have been made at a serious price, it is unlikely that many buying the wine will not understand the concept.

This is undoubtedly a superb champagne. Bright aromas permeate every nook and cranny with lemons, spices, florals, lemongrass, and a minerally backing. Ideally balanced with impressive length, this is ripe and exuberant (one suspects that the 2016 material contributes to this). There is complexity to be found here, and even notes of stone fruit, golden apples, and tobacco leaf, finishing with some pear and beeswax. Fresh, long, delicious, this will age and improve for more than a decade. 96.

Allow me a prediction. I think future releases (and there will be future releases, though possibly not every year) will be even better, as I think they will emanate from better base years. That said, this is a wonderful reappearance, a most welcome one.

Charles Heidsieck Blanc des Millénaires 2007

Charles Heidsieck has also released the latest vintage of its Blanc des Millénaires, the 2007 (AUD$400). Not 40,000 cases unfortunately, but around 8,000. The first release of this wine was the 1983, followed by 1985, 1990, 1995, 2004, 2006, and now the ’07. For me, this is the house’s best since that amazing 1995.

Two thousand seven might be a vintage that gets very little love, but do not neglect the Chardonnay-based wines. They are a bit special. As usual, this wine came from five villages in the Côte des Blancs. We have covered all this with past vintages so I won’t drag you through it all again, but they are Avize, Cramant, Oger, Le Mesnil, and Vertus – around an even split from each. More than 12 years on lees and a dosage of 7.3 grams/liter.

This wine is exquisite and beguiling, a glorious 2007. Lemongrass notes with ginger, citrus and fresh florals, jasmine, and lemon zest. A line of chalky salinity, a hint of green apple and the touch of honey on the finish. Good, bright acidity, knife-edge balance, and immense length. The previous release, 2006, was an excellent wine but riper and more powerful. This has class and finesse. Superb persistence with those notes of lemon, ginger, and florals all lingering. Twenty years ahead of it. 98.

I am delighted to see the Champagne Charlie make such an impressive return, but if I was forced to pick one, I could not go past the wonderful Blanc des Millénaires 2007. And how exciting that the next release will be the 2008 (well, I am assuming so as that is the sort of information that not even an FBI raid would uncover) and that we will have another Champagne Charlie. Bring them on!

For more information, please visit charlesheidsieck.com.

You may also enjoy:

Charles Heidsieck Champagne Charlie: A Man, A Bottle, A Legend

Charles Heidsieck Blanc des Millénaires 2006: Champagne Charlie Would Approve

Charles Heidsieck Blanc Des Millenaires 2004: Long Live The King Of Chardonnay Cuvées

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!