by Martin Green

When I first got into watches, I was fresh into college. Although I worked two jobs on the side to feed my growing addiction, even in those days it didn’t get me as far as I would have liked to go.

I wanted one of every kind of complication: although tourbillons, perpetual calendars, and the like were still far beyond my means, an automatic chronograph was doable. I ended up getting a Hamilton Khaki Chronograph, which I bought from its first owner and only paid a few hundred euros for.

While that watch has come and gone now, something did stay and that was my love for its movement: the Valjoux 7750. I became impressed by its performance and enamored by its little quirks.

While my knowledge deepened and I got to know other chronograph movements made by Lémania, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Zenith, and Frédéric Piguet, the Valjoux 7750 stuck with me. Of course, this is a personal preference, and one can easily make a similarly passionate statement about any of the other chronograph movements. But for me the movement itself, the stories behind it, and its performance on the wrist transformed it into my favorite automatic chronograph movement.

The story of the turtle and the hare

The history of Caliber 7750 started when Valjoux found itself in somewhat of a predicament.

In 1969 Zenith-Movado introduced its first automatic chronograph movement: the El Primero. And Breitling, Hamilton, Heuer, Buren and Dubois Dépraz had joined forces and launched the Chronomatic movement in that same year.

Zenith El Primero chronograph movement from 1969

That put Valjoux in a tight spot, and the company decided that it was up to its fresh hire, Edmond Capt, to get the company out of it. Valjoux not only wanted him to develop the movement as quickly as possible, but it also needed to be a robust, reliable, and accurate automatic chronograph that was relatively inexpensive to make and included a quick-set day and date.

As if this wasn’t enough pressure, by this time the Japanese were already conquering valuable market positions with their quartz watches, which would later have a major impact on the history of the 7750.

To speed up the development Capt used the Valjoux Caliber 7733 as his starting point, a manual-wind chronograph. This wasn’t his only advantage because Capt also had the help of Donald Rochat and a computer to make drawings and calculations. The latter may sound like a given now, but back then it was a rarity, even in the Swiss watchmaking industry.

What made the 7750 so different was that its operating system didn’t rely on column wheels, but rather on levers to operate the different functions of the chronograph using an oblong-shaped cam. This resulted in a reliable chronograph that could be mass produced much easier than its column wheel-operated cousins.

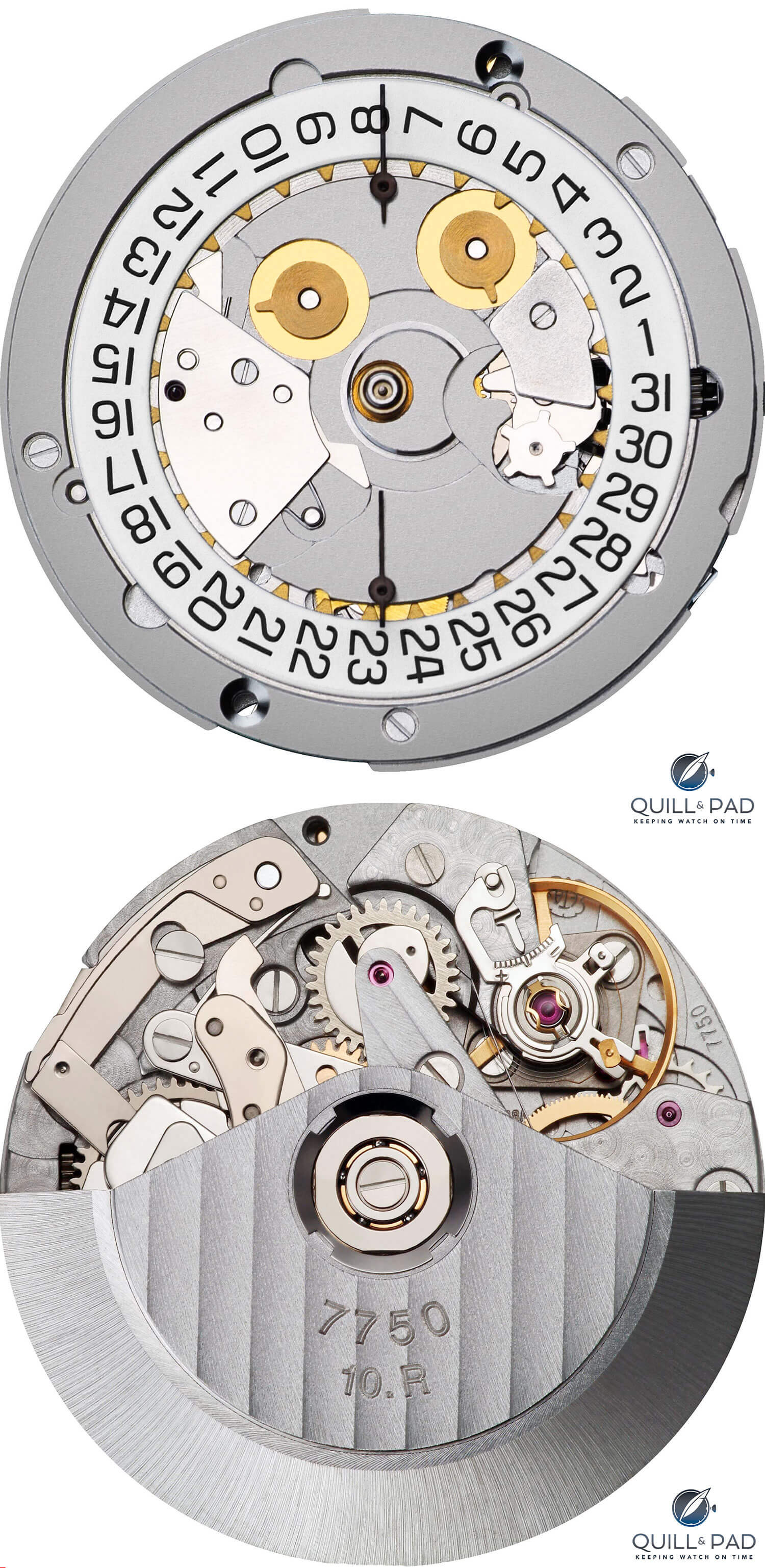

ETA Valjoux 7750 front and back

Capt and his team worked fast in creating what would become the Valjoux 7750. They worked so quickly that in 1973 the first movements were delivered to customers. But the Valjoux 7750 seemed to become a supernova, burning brightly for a very short time and then imploding.

By 1975, after only two short years, Valjoux customers felt the squeeze of the Japanese quartz movements to such an extent that orders plummeted and Valjoux decided to halt production of it completely.

Valjoux 7750: same script, different cast

Here the story takes a turn similar to that of the El Primero. Valjoux’s managers were convinced that the end of mechanical watchmaking was upon them and ordered the complete destruction of everything related to the Valjoux 7750. They trusted Capt to carry out these orders, but that is like asking a man to kill his own child. So Capt – like Charles Vermot at Zenith – simply stored everything instead of destroying it.

But then the unexpected happened. As the 1980s approached, there was a sudden a renewed interest in mechanical watches – and Swiss brands were in dire need of an automatic chronograph caliber to take advantage of this change in the wind.

Valjoux had joined Ebauches SA in 1944, which together with other important movement manufactures tried to regulate the production of movements. The quartz crisis brought it to the brink of bankruptcy, and they eventually ended up being consolidated into ETA, which became part of the conglomerate that we now know as the Swatch Group.

ETA’s main factory building as seen in 2008

The fact that Capt kept all the tools and drawings to make the 7750 was now considered a godsend, and production was resumed in the 1980s. From there on Caliber 7750, now belonging to what was referred to as ETA/Valjoux or simply ETA, would play a vital role in the fame and fortune of quite a few esteemed brands.

Valjoux 7750: powering progress

In 1984 Breitling was still in the hands of Ernest Schneider, who bought the ailing company in 1979 from Willy Breitling. It was the year in which the brand celebrated its centennial anniversary, and it did so with a completely new version of the Chronomat – powered of course by the Valjoux 7750. For its time it was a very large and robust watch, but even more importantly it would introduce a completely different design language, which would propel Breitling into a very successful chapter of its history.

IWC also quickly took a liking to the 7750, and it was technical director Kurt Klaus who used it as a base for what would become the legendary Da Vinci perpetual calendar chronograph. IWC was at that time owned by German instrument maker VDO Adolf Schindling AG, with Günter Blümlein at the helm as CEO (Blümlein would also later play a pivotal role in the resurrection of A. Lange & Söhne and the survival of Jaeger-LeCoultre).

Klaus himself received part of his education from Albert Pellaton, IWC’s famed technical director. When he was asked to develop a perpetual calendar with a chronograph, he took an entirely different approach than Capt. While computers were now available, Klaus used a calculator and sketched by hand.

IWC Da Vinci perpetual calendar chronograph

This makes the result all the more remarkable because not only did the Da Vinci combine a perpetual calendar with a chronograph, it also included a four-digit year indication. And the entire calendar could be set just by using the crown. Because it was based on the ETA Valjoux 7750, the watch was also very robust and reliable, something that cannot be said of all perpetual calendars, especially not those with additional complications such as a chronograph.

The Da Vinci was launched at Baselworld in 1985, and its success took even IWC by surprise, turning Klaus into a watchmaker with rock star status within the industry.

Valjoux 7750: complication upon complication

The Da Vinci wasn’t the only watch based on the ETA Valjoux 7750 that made a great impact on IWC, and again it was the genius of one man that made a difference. This time his name was Richard Habring, and he was asked to find an affordable way to create a split-seconds chronograph.

In those days you needed two column wheels to do so, but Habring took the ETA Valjoux 7750 and devised a clever way around this. The mechanism he designed was operated by a lever-and-cam system, his way of thinking continuing along the same line as Capt’s when he initially designed the 7750.

The fact that this solution also resulted in an extra pusher at 10 o’clock to operate the rattrapante was actually an advantage. It provided a subtle difference between IWC’s Fliegerchronograph (pilot’s chronograph) and Doppelchronograph (split-seconds chronograph), something that owners of the latter probably greatly appreciated.

IWC wasn’t done with the 7750 yet, though. In 1993 the brand celebrated its 125th anniversary with Il Destriero Scafusia (the “Warhorse from Schaffhausen”). This watch combined a perpetual calendar, split-seconds chronograph, flying tourbillon, and minute repeater. While somewhat disguised, the layout of the 7750 is still visible from the back, though the flying tourbillon and Habring’s rattrapante setup can cause distraction.

IWC wasn’t the only firm using the now-ubiquitous 7750 as a base for more complicated creations. In the 1990s Fortis became the partner of the Russian Roscosmos space program, and in 1994 its first official cosmonaut’s watch went into space as part of the standard equipment of the Russian cosmonauts, also worn by those in the International Space Station (ISS).

Fortis B-42 Cosmonaut Chronograph alarm

However, as timing is critical in space the cosmonauts soon requested their chronographs also be equipped with an alarm function. To achieve this Fortis enlisted the help of independent watchmaker Paul Gerber to create the world’s first automatic chronograph with alarm function.

Gerber used the 7750 as a base caliber, then added a second spring barrel to power the alarm, which was also wound by the movement’s rotor, which was slightly enlarged and made heavier to wind two barrels efficiently. To create room for all this, Gerber raised the rotor 1.5 mm higher.

This movement, named F-2001, was launched in 1998. In 2012 Fortis celebrated its centennial anniversary with an even more complicated version of that movement, which now also included a GMT function as well as a power reserve indicator for both barrels.

Porsche Design Indicator movement

Hardly recognizable as such, but still outfitted with a 7750 as a base movement, is the Eterna 6036, which powers the Porsche Design Indicator P’6910. This watch displays the elapsed hours and minutes of the chronograph function with jumping indicators at 3 o’clock combined with a power reserve indicator and running seconds. To achieve this, more than 800 different components are needed.

Renaissance of mechanical watchmaking included a lot of Valjoux 7750s

When the renaissance of mechanical watchmaking was in full swing, ETA Valjoux also began offering more complicated versions of the 7750, most notably the 7751, which combined the chronograph with a full calendar and a moon phase display.

Less well known is the 7758, in which the hour counter makes room for the moon phase, though the date remains at 3 o’clock. For those who preferred the more balanced tricompax layout of the chronograph functions, ETA also introduced the 7753 with its subdials positioned at 3, 6, and 9 o’clock.

As the interest in mechanical watches increased, so did the knowledge of collectors. Cam vs. column wheel became – and still is – a favorite discussion point, with quite a few preferring a column wheel to control chronograph functions.

This enticed some movement specialists to modify the 7750 by incorporating a column wheel. Alfred Rochat did this for example for Chronoswiss and La Joux-Perret for Panerai, Graham, Chopard, and Hublot. Although this of course went against the grain of Capt’s original design, it did provide these brands with column-wheel chronographs that were still much less expensive to make than if they had opted for a movement that was developed to include a column wheel from the beginning.

As watches increased in diameter, the 13 lignes (or 30 mm) of the 7750 were not enough to amply and elegantly fill cases, so ETA developed the Valgranges line. This increased the movement diameter by more than 20 percent to 16 lignes or 36.6 mm, while offering the same complications.

ETA Valgranges movements

Interesting to note is that this collection also includes several versions that lack a chronograph function, essentially creating a robust movement that combines the time with a date and perhaps a power reserve complication.

That was however not the first time that the 7750 was used in this way. Panerai took away all the parts supporting the chronograph function, leaving only the date at 3 o’clock and the running seconds at 9 o’clock, to turn the 7750 into its OP III caliber.

While this may look strange, it is also a testimony to the robustness of the movement itself. And it was a relatively easy way for Panerai to obtain an automatic movement that featured a date as well as subsidiary seconds at 9 o’clock, which fit nicely with that brand’s “DNA.”

You can strip down a Valjoux 7750 or build it up

In 2009, Longines wanted to strengthen its position in the chronograph market with an automatic column wheel-controlled movement. So the Swatch Group-owned brand took an ETA Valgranges A08.L01, which in itself was based on the 7750, and equipped it with a column wheel, vertical clutch, oscillating pinion, and a self-adjusting. two-armed reset hammer to create Longines Caliber L688.

It was this movement that Omega used as a base to create its own Caliber 3330, adding a co-axial escapement and a silicon balance spring.

Bread and butter

Forty-five years after the first 7750s were delivered to clients in 1973, the Valjoux 7750 is still going strong.

It can look back on a distinguished history powering an incredible variety of watches and serving as the basis for some very complicated conceptions.

Chronoswiss Opus on the wrist: believe it or not, this watch is powered by a skeletonized Valjoux 7750

It was the movement that made the Chronoswiss Opus 1996’s Watch of the Year in Germany and it also formed the basis of Marc Newson’s smartest mechanical watch, the Ikepod Megapode.

It is the movement that can be found in a humble Hamilton or an exotic Franck Muller; the one to power a generation of IWCs, Breitlings, and Omegas; and it strongly remains to this day the motor of current collections of so many other brands as well.

While watch snobs may look down on the 7750, they are probably also unaware of the delight that freshly baked bread with a generously applied layer of butter can offer.

* This article was first published on September 22, 2018 at Valjoux 7750: The World’s Greatest Chronograph Movement By Far (By Popularity And Numbers).

You may also enjoy:

Here’s Why: The Chronograph Is The New Tourbillon

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Absolutely a very informative and useful article. Thank you!

Nice article but whereas one image shows El Primero’s column wheel mechanism, the unique 7750 mechanism, the subject of the article, is obscured. Sorry but this is a disappointing piece of technical writing which should have been jumped on by the editor. (Or any author who re-read his work before pressing “send”)

Hi Tim, I’m not sure what it is that you are criticizing. The text above and below that first image of the El Primero explains that the history of the Valjoux 7750 began (in part at least) with the El Primero, hence the image of the El Primero movement (for reference and comparison with what follows.

If you are criticizing the writing, why start with a reference to the El Primero image? If you think the first photo should have been of a 7750, why not say that? I would have preferred the first image to have been of a 7750, but thought that might confuse some readers when the text surrounding the image referred to the El Primero.

Or have I missed something (which is entirely possible if not probable)?

Regards, Ian

I think he wanted to see a picture of the 7750 without a rotor so you could see the cam and gears of the chronograph. The El Primero movement image lacks the rotor, so you can see all the greasy bits and thereby better understand the text description of how they work. Without a view of the 7750 fully exposed, it’s a bit difficult to understand what’s being described.