How Long Can We Age Champagne, Should We Age Champagne, And Is Late Disgorged Or Aged On Cork Best?

by Ken Gargett

Champagne is a lot more robust than people think. While reds and even whites get a fairly rough hand on occasion, there is a feeling that champagne must always be handled with the proverbial kid gloves. Now, all wine should be treated as gently as possible and left undisturbed in the cellar until you are ready to bring out the bottle and enjoy it, but the best laid plans . . .

Perrier-Jouët’s champagne cellar

When discussing or presenting champagne, I am often asked how long it can be kept. The answer is far longer than we sometimes suspect. The question should be perhaps how long do we want to keep champagne before drinking it. Another regular, and related, question is, what is a late-disgorged champagne and is it better than normal champagne?

As Charles Curtis puts it in his excellent book on champagne vintages, Vintage Champagne 1899 to 2019, “Do you prefer bright, newly disgorged champagne or do you start to swoon only when it reaches 20, or 30, or 40 years from the vintage date? Do you prefer champagnes with extra time on lees or those that have much post disgorgement aging and relatively less time on the lees?”

This is a question that anyone half serious about champagne must answer and they can only do that for themselves. And only then by trying as many examples of each as they can.

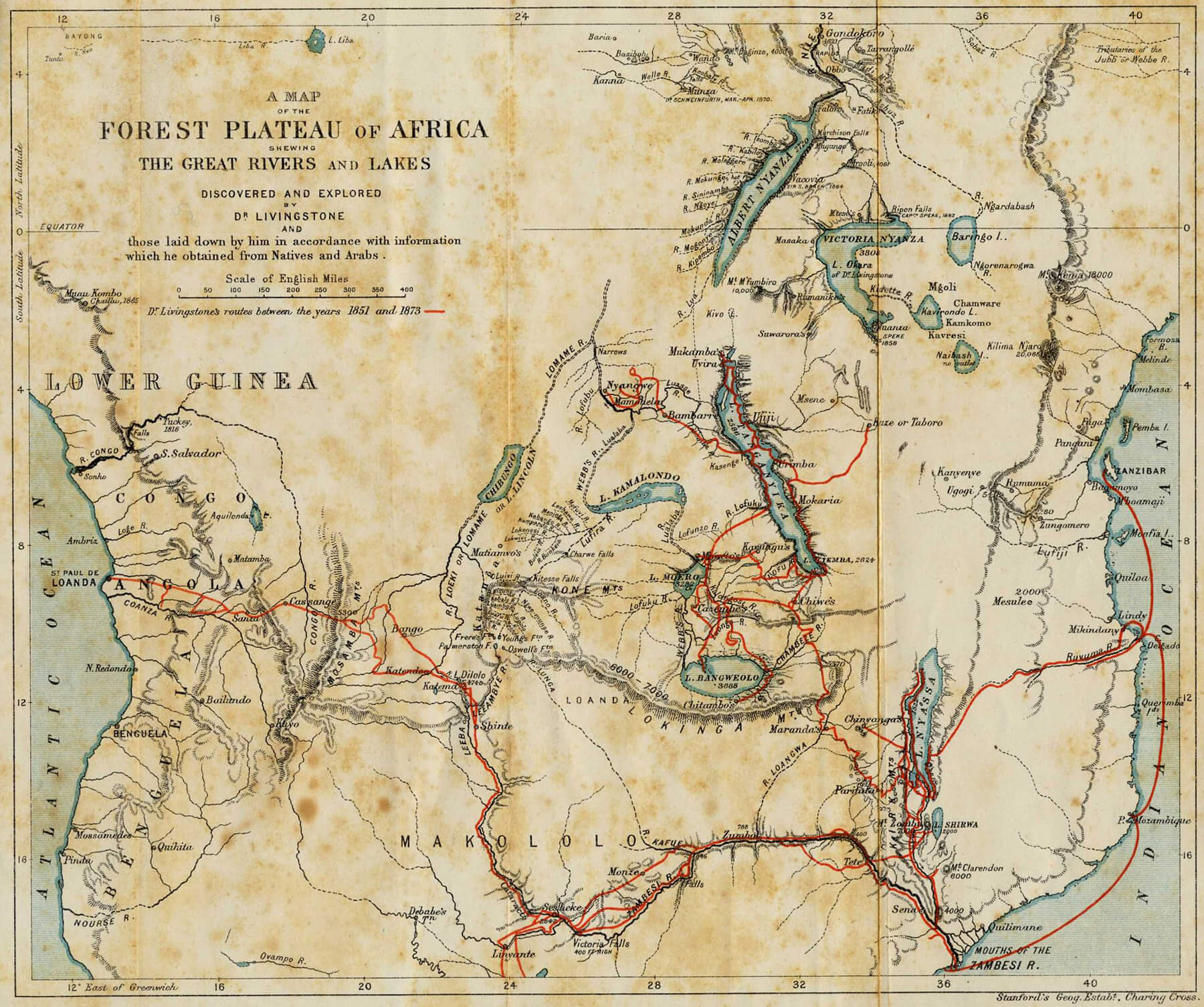

Dr. Livingstone, I presume? A favorite story illustrating how champagne can age

One of my favorite stories about this wonderful wine comes from the most unlikely source: African exploration. Every schoolchild, at least of my generation, was told the story of the Scottish missionary and explorer, Dr. David Livingstone, and how he was supposedly lost in the wilds of Africa, no one having heard from him for around half a decade. He was finally “discovered” by American journalist Henry Morton Stanley, who uttered the immortal words, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume.”

Map of the travels of David Livingstone in Africa, 1851-1873 (photo courtesy Gutenberg Project/Wikipedia)

What happened next was never the subject of our young lessons, but there are versions. One suggests that Livingstone then said, “I feel thankful that I am here to welcome you,” but Stanley removed these pages from his diary and Livingstone’s suggests no evidence of that. An alternative scenario from Stanley’s diary – and given his character this is something that seems far more likely – Stanley then brought forth a bottle of champagne and, on the banks of Lake Tanganyika, opened and shared it with the missing missionary.

They record how glorious the foaming liquid was, raved about the quality of the wine, and noted it as a “Sillery.” Sillery is one of the great Grand Crus of Champagne, but its use on labels has been extremely limited for many years. Houses might name their wines a Grand Cru, but very rarely then name which Grand Cru. Still, that the name Sillery was recorded at the time does give one some confidence that the report is true. Even today it is still highly regarded. Fruit from vineyards in Sillery often ends up in wines like Dom Pérignon.

So where am I going with all this? Stop for a moment and think about this.

Stanley’s editor at the New York Herald, James Gordon Bennett Jr, wanted to show up the Brits (he was decidedly not fond of our friends from Great Britain) by finding the Scottish missionary, given that the British had not managed to do so (or, in Bennett’s view, not even bothered to try). That it would boost the circulation of his already popular paper was a bonus. So Stanley was dispatched to find him. Bennett was apparently unaware that Stanley was actually British, even though he had fought in the U.S. Civil War (for both sides at different times).

In those days, an expedition to rescue Livingstone was a massive undertaking. It involved lengthy sea travel and much more. If our friends were to have the opportunity to enjoy a bottle of champagne if and when Stanley located Livingstone, the only way to do so would be for Stanley to bring the supplies with him. No picking up a bottle at the local markets on the way through the swamps. So our bottles head off on board, but certainly they would not be in refrigeration at the time.

Then, once he had arrived in Africa, Stanley and his porters set off on their search. For some three months they crossed deserts, traversed mountains, forded raging streams, slogged through fetid swamps, and fought skirmishes with the locals, some of whom they believed to be cannibals. They endured searing heat and suffered freezing cold temperatures. Through all this, the porters bounced the supplies around on their backs and heads or in boxes on any mule so fortunate as to have survived the diseases, predatory animals, and heat.

And, yet, when the long-suffering bottle of champagne was pulled from the supplies on the banks of Lake Tanganyika to celebrate the moment, it was described as ‘”glorious.” Treatment like that should have seen the poor thing rendered undrinkable at best (there are some who subscribe to the theory that after what they had both been through, anything would have tasted glorious, but I like to believe that they actually found the wine to be in good shape).

In other words, champagne can take a great deal more punishment than we sometimes think. Of course, as they say in the classics, don’t try this at home.

What is disgorgement?

During the champagne method of making sparkling wine, the second fermentation occurs in the bottle when the makers have added a little sugar and yeast (liqueur de tirage). The yeast consumes the sugar, creating CO2 and alcohol, and as the wine is sealed the CO2 gas cannot escape (creating those bubbles). Meanwhile, the yeast eats itself to death as the alcohol it has created as a byproduct of this process eventually kills it. This means you have dead yeast in the bottle – called the lees – and that is not a selling point. No one wants cloudy, silty champagne. So we need to get rid of it. But first, the time that the wine spends on these lees helps it to build complexity and character.

Inverting champagne bottles (photo courtesy www.champagne.fr)

The process for ridding bottles of this unwanted excess was eventually developed by the widow Clicquot, who slowly inverted bottles so the dead yeast slid to the base of the seal; she did this by carving holes in her kitchen table and putting the bottle on an angle.

The inversion of the bottles has to happen slowly; if it is done quickly then some of the muck sticks to the sides of the bottle. When the lees are finally on the base of the upended cork, it is frozen and the seal quickly removed. The plug of dead yeast shoots out and a small amount of wine with a little dosage (usually) is inserted into the bottle, which is then sealed again.

Pol Roger champagne disgorgement line (photo courtesy Tomaser/Wikipedia)

So, in a nutshell, late disgorging is when the wine spends a lot longer on its lees before going through that process, and then is usually sold without any great length of time aging on cork.

We are seeing more and more, although sadly not all, champagne houses putting the disgorgement date on the back labels. This gives the consumer vital information as to whether the wine has recently been disgorged or whether this happened some time previously.

It matters. It won’t indicate the quality of the champagne, but it will give a clue as to what it will be like in general. You may have two bottles of, say, non-vintage Moet et Chandon on the shelf before you. If you can see disgorgement dates, you can get some idea as to whether the champagne will be very fresh or whether it might have been there for some time.

How long can champagne age?

The oldest champagne I have seen was a half-bottle of 1900 Deutz, which had lost its fizz – no surprise – but was still fascinating drinking, like a very old white.

A 1914 Pol Roger was certainly fresher (I suspect that this might have had far more time on lees than was usual). A 1928 Krug from the Collection series was also largely bereft of bubbles but still a brilliant, aged wine, complex and textured. Although lacking fizz in the glass, there was a prickle/sparkle on the palate. I am told that is because old champagnes will sometimes have lost the fizz that would appear in the glass but still have a touch of CO2, which gives this sparkling impression.

1907 Heidsieck Monopole Gout American

I have discussed the bottles of the extraordinary 1907 Heidsieck Monopole Gout American previously and how that despite almost a century on the bottom of the ocean, one of the bottles opened foamed up and out like a brand-new vintage. Others showed far more age and maturity – it does show that at these sorts of ages, bottles can vary considerably.

For many years, the Champenois would always insist that they released their wines at the perfect time for drinking them. They were ready at that moment.

Now that is all well and good, but it does reek a little of self-interest. Of course they’d say that. Just means that you need to keep buying. What tended to get up some Champenois nostrils was what they termed le goût Anglais. Basically, this referred to the English preference for aging champagne before drinking it, and it gave many French an excuse to add another item to the long list of reasons to disparage the British.

Le goût Anglais is basically a preference for champagne that has been aged. Really, it is simply a matter of personal preference. I have friends who think that all champagne should be opened as soon as possible; others for whom opening a bottle before it has had a chance to spend decades in the cellar increasing in complexity is a crime against humanity.

Personally, I think there are champagnes that fit both categories. Plenty of fine non-vintage champagnes will be at their best when they first hit the shelves, exhibiting freshness and vitality. Others, some of the great vintages and the prestige champagnes, will benefit from more time in the cellar. You just need to work out what you like.

It is, however, no longer quite as simple as it once was. The category of late-disgorged champagnes has muddied the waters somewhat. These are basically champagnes that are ready for release but a then given more time on the yeast lees before they are disgorged and sold.

Bollinger R.D. 2007 champagne

The most famous example is the Bollinger R.D. The “R.D.” stands for “recently disgorged.” Basically, it is the “standard” Bollinger vintage, which has been held back on its lees and then released, having gained extra complexity from the procedure. If drunk reasonably soon after that delayed release, there should still be a degree of freshness and vibrancy. At the other end of the spectrum, if that extra time was spent on cork, there would be complexity certainly, but it would be much more mature, richer, perhaps offering toffee and honey flavors.

Is either style preferable? I would say different rather than better, but the late disgorged champagnes do have one advantage: despite the experiences of our intrepid African explorers, the longer a champagne spends under cork the more chance it has of falling out of condition.

Reflecting on an extraordinary tasting

I went back over some of the champagnes served at the extraordinary tastings held annually in Helsinki, which included both styles. In looking at these, remember that corks play a massive role and that at these ages the old saying about “no great wines, only great bottles” should really be “no great wines, only great corks.”

A 1959 Charles Heidsieck was showing amazing life with length and complexity. A 1955 Veuve Clicquot was still full of interest but had seen better days. Both a 1979 Heidsieck Monopole Diamant Bleu and Mumm Rosé from 1973 had struggled to stay the course. The 1964 Dom Pérignon, however, would make you believe angels had arrived on earth for the sole purpose of extending hitherto unforeseen pleasures. All champagnes that had been aged further under cork.

Looking at champagnes that had undergone late disgorging, a 1996 Philipponnat Clos des Goisses was glorious while a 1996 Dumangin Chigny les Roses Vinotheque was impressive but it really had not survived quite as well as one might hope. Another from 1996, the Pierre Gimonnet Special Club was intriguing without being scintillating, whereas the 1996 Duval Leroy Femme, another late disgorged style, was creamy and complex.

The 1990 Veuve Clicquot Cave Privée was half and half. Having been disgorged in 2008 (so a later disgorged style, but also time on cork for aging further). The result seemed to suggest it really was not one thing or the other. A bottle of the 1990 Jacquesson disgorged in 2005 suffered the same fate. A 1990 Bollinger R.D., disgorged in 2003, had some positive aspects but again not the greatest bottle.

The Telmont Grand Couronnement Grand Cru Brut 1998, another Vinothèque style (another way of saying late disgorged), was beautifully perfumed and balanced with immaculate length. A 1999 late disgorged Cattier drank more impressively than any of us imagined it could. And right up with it was a magnum of late disgorged Pol Roger from 1999.

But then, in contrast, a bottle of 1998 Piper Heidsieck Rare aged on cork was extraordinarily good.

And so it went. A 1993 Veuve Clicquot La Grande Dame, aged on cork, was looking magnificent; the 1995 less so. Also superb was a 1998 Krug and the Clos de Mesnil from that vintage as well as the Charles Heidsieck Blanc des Millenaires 1995. The late disgorged styles from Palmer and Billecart-Salmon impressed. The 1995 Henriot Enchanteleurs, from time on cork, superb. We could go on.

Perhaps the superstars were the Plenitude series from Dom Pérignon. These were uniformly stunning. The 1998 P2, 1990 P3, 1995 P2, 1995 P2 Rosé, and, perhaps the pick of the lot, a 1988 P3 Rosé. The Plenitude concept is something that I will be looking at very soon so I will not go through it here other than to say that the winemakers at Dom Pérignon decide when to release their wine. Then they hold some back on lees for a subsequent release (the P2 series) and some for a third release (the P3 series) even later.

Magnum of Mumm champagne vintage 1961

Does all this shed light on which style works best?

So does this tell us which method works best? which Not really. There were wonderful champagnes from both styles and lesser ones as well. The style that did not fare so well on the day was the half/half, where a late disgorged style then saw time on cork. But then, as many prestige champagnes have extended time of lees before they are disgorged, without technically being “late disgorged” styles, I am really not sure if we have learned anything other than both styles can have their successes and failures.

So where does all this leave us? To be honest, I am not sure we have got anywhere at all. So many houses are giving their wines extra time on lees these days that the concept of late disgorged has blurred. Aging on cork is very much as it has always been. Good cellaring conditions are essential and you should pick your wines.

While multi-vintages from producers like Krug will age and improve for many years, many don’t. But the top years will age magnificently: 1988 is still brilliant and good bottles have time ahead of them; 2008 is a recent vintage that will give decades of pleasure.

One factor to consider is that bottles aged for lengthy periods on lees in the cellars of the champagne houses (or even on cork) will always cost far more than if you buy an original release and age yourself – but only do this if you have the correct cellaring conditions.

Piper-Heidsieck Hors-Série 1971

The idea for looking at all of this came about because of a few wines encountered recently. I met the amazing 1971 Piper-Heidsieck Hors-Série, and Mumm recently held tastings that included a couple of great examples for both sides of the argument. Mumm’s Cuvee Lalou 2006 aged on cork (another champagne I have looked at previously and one that is now part of the RSRV series) and a magnum of the 1961, which had been disgorged just 18 months ago (sadly, this one is not commercially available).

So a champagne that had basically spent half a century on lees. This was never going to be the bright, vibrant, effervescent style we might see in a non-vintage. Seventy-one percent Pinot Noir from Grand Cru vineyards in the Montagne de Reims – Verzenay, Verzy, Ambonnay and Bouzy – with the remaining 29 percent Chardonnay from the Cotes des Blancs. The dosage is four grams/liter.

What can one expect from a wine that has spent 50 years on lees? As I said, not the vibrancy of youth, of course. This was deep gold with coffee bean notes, honeycomb, and even cigar box touches. Certainly still fresh but seriously complex. Notes of ripe stone fruits and glacé mandarin. Almost chewy in texture. Wonderful mature, complex champagne. I had it 98. But then I had the 2006 Lalou at the same score.

Taittinger Champagne

Late disgorged or aged on cork? Both offer so much. Take your pick.

You may also enjoy:

Bollinger R.D. 2004: When It Came To Champagne (And Much Else), Madame Bollinger Had Excellent Taste

Piper-Heidsieck Launches Hors-Série 1971 Champagne: An Incredible 48 Years On Lees!

Mumm RSRV R. Lalou 2006 Champagne: A Revelation (With Or Without Usain Bolt)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Interesting from one who’s family makes champagne, a small grower producer it depends on a few variables. I happen to prefer a young champagne.

Josette

Hi Josette.

Many thanks for the comments. I have many friends who would agree with your, preferring younger champagnes. Do your grower champagnes make it to Australia?