Apostelwein Vintage 1727: How does a 3 Hundred-Year-Old Wine Taste? Sensational!

by Ken Gargett

Old wine is always a lottery. The provenance, the chances of the wine being a fake (an entire topic just in that alone), did the cork hold up, how was the storage, and so on.

I also have a theory. We are continually told how wine gets better with age. How often have we all read about something “maturing like a fine wine.” We are constantly told that old is better when it comes to wine. It is not always so. Sure, for many of the world’s great wines, time in the cellar is an essential component. For a majority of wines, though, they really are made to drink young.

Figures suggest that the vast majority of wine is purchased to be drunk almost immediately. In Australia, we are often told that 98% of all wine purchased is drunk within 24 hours. I doubt it is much different in many other countries. So, simply aging any wine will not always make it better. Often, the reverse.

I have a second theory (two for one, today, no extra charge). Most people prefer young wine. That is simply because they have almost no experience with old wine and when they see one, it is often so different to expectations that it is dismissed. Or at the very least, found to be confusing.

That said, genuinely great wine really does almost always include an aging component. That extra time allows the best wines to develop secondary and tertiary characters, rather than just the primary fruit flavors. It allows extra complexity to build.

————————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

As good as top young Riesling, Semillon, Champagne and many other whites are, that extra time allows the extra complexity to take them to a new level. Reds, even more so. Today, while many wines are made to be far more approachable as young wines than they ever were, that does not mean there is no room for improvement.

Some years ago, on one of my regular jaunts to a friend’s tasting (and wine competition judging) in Scandinavia, I was invited to a small tasting the night before the real work began. Truly mind-boggling – everything served blind. After a couple of stellar champagnes, which included a magnum of the Dom Perignon P3 1973, a small glass was handed to each of those in attendance, about eight of us (small as it came from a 50cl or half bottle).

While a cavalcade of fabled wines followed – 1923 DRC La Tache, 1929 DRC Romanee-Conti, 1870 and 1982 Lafite, 1950 La Fleur, 1950 Cheval Blanc, 1953 Petrus and the red and white versions of the 1945 La Chapelle – this was the one that caused most head-scratching. For me, the nose was that of an extremely old nutty Oloroso while others saw Madeira-like characters. No one expected a non-fortified table wine, but that is what it was. The 1727 Rudesheimer Apostelwein, Bremer Ratskeller.

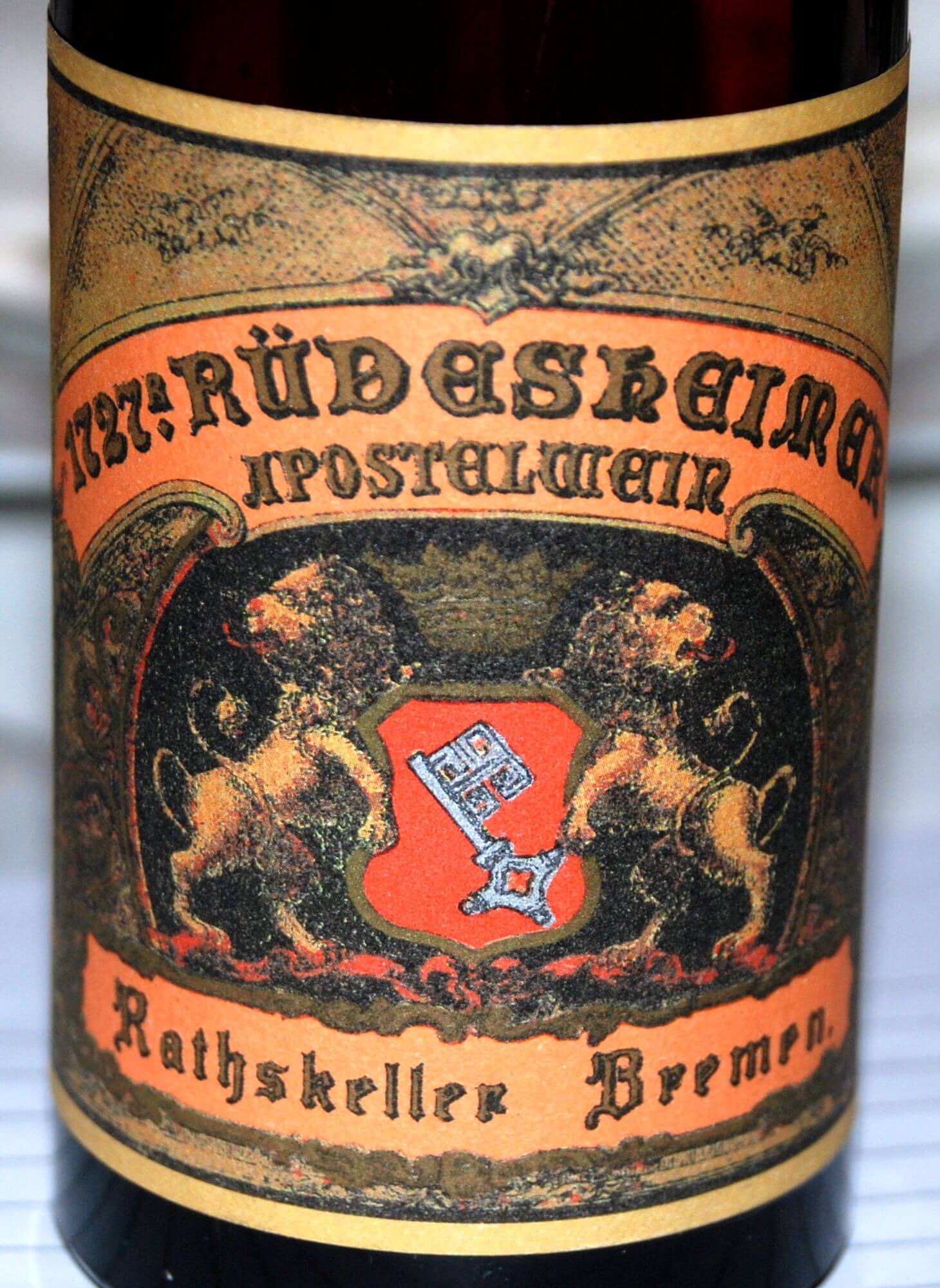

1727 Rüdesheimer Apostelwein (photo courtesy www.oldest.org)

A little research at the time provided a number of theories as to its history.

We assumed Riesling, but in truth, for a wine that ancient, every chance it is a blend of various varieties – whatever happened to be in the vineyards at the time.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

One report, from a tasting in the Bahamas (well, just as likely as Scandinavia, I guess), reported that the Graycliff Hotel in Nassau had a bottle that they priced at US$200,000. That would exceed prices, even though it is extremely rare, suggested by Winesearcher today. There, the one half-bottle which is on offer at the moment – in France – is offered at A$30,000.

The Bremer Ratskeller in Bremen

My Scandinavian friend had tried it half a dozen times before that evening, so probably knows the wine as well as anyone. At the time, he advised us that it had been a combination of three vintages held in barrels in the ancient Bremer Ratskeller winery, 1683, 1717 and 1727. The town of Bremen owns the Bremer Ratskeller winery. The cellar is under the town hall and apparently, town councilors do have access to the barrels (so perhaps evaporation is not the only culprit as is about to be suggested below).

Wine barrels stored in the Bremer Ratskeller cellar

Many, many years ago, there were twelve barrels of these wines, but evaporation reduced the contents, and they were blended into a single barrel. The Apostelwein name came from the fact that originally there were those twelve barrels. Apparently, that final barrel had been dubbed the ‘Judas’ barrel. Make what you will of that.

The barrel/bottles were labeled 1727, as this was the youngest vintage in the mix. But who really knows? My friend believed that 6,000 half bottles of this wine had been taken from the barrel, bottled, and then offered for sale back in 1960. The alcohol is believed to be extremely low, as can happen with certain German wines with considerable sweetness. One suggestion was that the wine had 300 grams/liter of sugar.

The reports that still exist suggest that 1727 was a great vintage in the region. No surprise there.

Michael Broadbent, who ran Christie’s wine auctions in London for many years, has stated that his/Christie’s first record of the wine dated back to 1829, when a dozen bottles were sold for the sum of five pounds. He noted that this was a considerable amount at the time.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

There is a famous practical joke thatwas played in relation to this wine. The godfather of Australian wine, Len Evans, had sourced a bottle and was featuring it at a very special dinner for some close friends in Sydney, many years ago (first half of the 70s). Evans had even included the Australian Prime Minister of the day, Malcolm Fraser, as a guest. As the time for serving the 1727 grew closer, anticipation reached fever pitch. One of Evans’ friends, Anders Ousbach, was acting as sommelier for the evening.

As Evans announced the imminent arrival of the 1727, with all the pomp and ceremony that only he could muster, a god-awful crash came from the kitchen. Out came Anders’ voice, “Sorry Len. Any chance you have a bottle of the 1728?” Apparently, Evans almost needed a defibrillator, but Anders emerged with the unscathed 1727. Seems he had waited for the precise moment and then smashed an empty bottle in the kitchen.

Interestingly, Broadbent has described the wine, which I believe he saw twice, both in terms of it resembling an old Madeira, and also an aged sherry.

Label of the 1727 Rüdesheimer Apostelwein

For me, as well as the nose resembling the nuttiness one might see with an extraordinarily old Oloroso sherry, it was surprisingly drinkable. Great complexity, there were also notes of leather and smoke and rather lovely, caramelized ginger. The sweetness was still more than apparent, but the wine was balanced. Better days? Sure, but still an amazing experience. It is one of those wines so difficult to score. Based purely on what was in the glass, I gave it 93. But how much do we give (or in other cases, subtract) for the interest, history, the fact that a wine pushing three centuries was still enjoyable, even if perhaps past its peak?

For what it is worth, I mentioned that my friend had seen half a dozen examples. He told us that they had varied enormously in quality, as one would expect for something of this age. This one was neither the best nor worst he had tasted.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

So what induced me to write about this now, especially given the tasting was seven or eight years ago? Well, it is not often that one has the chance to enjoy a once-in-a-lifetime wine twice, but just recently, another bottle came my way. Again it was from my most generous friend in Scandinavia when a group of us gathered to judge the Best Wine in the World competition for this year.

His most recent bottle far exceeded the first one, for me. Served blind, no one got close to picking what it was. No one got close to picking the century!

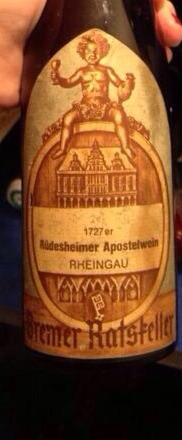

1727 Rüdesheimer Apostelwein (photo courtesy Vivino.com)

Incredibly complex, rather elegant and still with hints of sweetness. Orange marmalade was a noticeable character here. For me, it reminded me for all the world like a mango croissant (I have no idea whether anyone has ever made or tasted a mango croissant but if they had, I believe that this is what it would taste like).

There was a character like a hint of teak on the finish, which lingered seemingly forever. Some also found the merest hint of quality blue cheese and I could see that. An extraordinary wine. This time, for me, 99.

In case you are wondering, what else was happening back in 1727, King George I died from a stroke and was succeeded by his son, King George II (who allegedly later passed away from the decidedly unregal mode of death, diarrhea). Sir Issac Newton also passed away in 1727, while the famous English portrait artist, Thomas Gainsborough, was born. Sir George Washington would not even be born for several years yet. As for us Downunder, it would be more than sixty years before the First Fleet would even arrive.

This wine was nothing if not an extraordinary glimpse into history.

You might also enjoy:

The Joy Of Port, Especially Vintage Port (With Tasting Notes)

How Long Can We Age Champagne, Should We Age Champagne, And Is Late Disgorged Or Aged On Cork Best?

Tips For The Wines And Vintages To Buy In 2023

Strange Laws in the World of Wine and Spirits: The Good, The Bad, and The Idiotic

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!