Khanjar and Qaboos Rolexes: Are they the Vintage Watch Industry’s Blood Diamonds? (Updated with New Information)

Desirable artifacts sometimes come with uncomfortable truths

On May 18, 2018, a Rolex Daytona chronograph Reference 6263 known as the Red Sultan sold at auction by Phillips for more than 1.2 million Swiss francs.

Rolex Daytona chronograph Ref. 6263 ‘Red Sultan’ (photos courtesy Phillips)

This is a recent example of serious watch collectors expressing increasing interest in vintage watches (mostly Rolex, and to a lesser extent Audemars Piguet, IWC, Patek Philippe, and even Seiko) bearing either the Sultanate of Oman’s khanjar (traditional Omani dagger) and crossed swords emblem or the signature, usually in red, of the current Sultan Qaboos bin Said Albu Saidi (قابوس) on the dial.

The author’s 1960s Omani khanjar (photo courtesy Colin Alexander Smith)

Increasing demand for watches with the Omani emblem is understandable given the high quality, good condition, demonstrable provenance, and rarity of most of these watches, combined with the fact that they had often been presented to their first owners in the 1970s by Sultan Qaboos in person as a token of gratitude for services rendered to the then nascent sultanate.

They are therefore comparable to watches produced by Rolex for the Peruvian Air Force and French diving company Comex, especially where a special dial was printed for the watch, thereby guaranteeing its rarity.

Other very sought-after “Omani” timepieces include sports/diving watches such as the Reference 1665 Rolex Sea-Dweller, Reference 1675 GMT Master, and Reference 16800 Submariner, often presented to Oman’s army and police forces, and more classic styles of dress watches such as the Datejust and Oyster Perpetual, often in gold.

Some of these watches are in pristine condition, having been treasured by their owners in their presentation boxes, while others, having been exposed to the Omani heat and humidity have developed pleasing patina on the hands and indexes.

Rolexes as rewards for bravery

Of particular interest to European and especially British collectors were the watches believed to have been presented by Sultan Qaboos to members of Britain’s official and mercenary military staff who were involved in the 1970 coup where British forces arranged for Qaboos to depose his father, Sultan Taimur, who had ruled Muscat and Oman (as it was then known) as a medieval backwater since 1932.

“Red” (referring to the color of the Omani emblem) Rolex Khanjar Sea-Dweller (photo courtesy www.vintage-db.com)

According to Daniel Bourn’s very informative article on vintage-db.com: “The Rolex 1665 Omani Sea-Dwellers with either RED Khanjar or Qaboos dial script, were commissioned by Sultan Qaboos bin Sa’id via Asprey of London in the early 1970s and presented to the British Military SAS troops who had served in Oman during the Dhofar rebellion between 1970-1976.”

Bourn goes on to state that some 80-90 red Khanjar Sea-Dwellers ordered by Sultan Qaboos via Asprey in London rather than directly from Rolex in Switzerland (more on this later) were presented to military staff. The whereabouts of around 30 of these watches is known.

“Gold” (referring to the color of the Omani emblem) Rolex Khanjar Sea-Dweller (photo courtesy www.vintage-db.com)

Interestingly, four “gold” Khanjar Sea-Dwellers have also come to light, which on a purely statistical basis suggests that some 9-12 gold Khanjar watches were presented (gold considered more prestigious than the red Khanjar), and that this number might correspond to the nine SAS members who took part in the battle of Mirbat on 19 July 1972, where nine SAS members saw off an attack by 250 Dhofar rebels. The battle has allegedly been compared by some to the Battle of Rorke’s Drift.

However, in an update to my previous information, I spoke recently to a UK-based Rolex and Patek Philippe collector going by the name of the “Watch Baron,” who bought one of the gold Khanjar Sea-Dwellers about seven years ago after hearing the story of the “Mirbat nine.” He has since sold the watch, but says that curiosity got the better of him and that, armed with one of several books that relate the Mirbat story, he managed to track down one of the former SAS members involved.

When asked whether he had been awarded a gold Khanjar Rolex Sea-Dweller for his involvement, the SAS man laughed incredulously and replied categorically that neither he nor his colleagues received any recompense of any sort for their role in that battle, let alone a Rolex. Former SAS men being what they are, and given the clandestine nature of British military involvement in Oman at the time, one might argue that “he would say that, wouldn’t he?” But Watch Baron assures me that from the manner in which said SAS man responded, he is 99.9 percent sure that he was telling the truth.

Unless somebody comes forward to confirm it, it is therefore perhaps time to put to bed the Mirbat Rolex myth that has through constant repetition become accepted as gospel truth among collectors, even though it was only ever put forward as a mathematical hypothesis (see Mythbusting: 3 Persistent Patek Philippe And Rolex Myths Debunked for more).

My own theory, which is just an educated guess and no more valid than anyone else’s, is that in the absence of clear provenance of any of these Khanjar Sea-Dwellers from the early 1970s, they may have been presented to the assorted crew of British officers and “political residents” who both organized the 1970 coup and oversaw the transition of power to the new Sultan for several years thereafter and can be seen posing stiffly behind their young protégé in many photographs from that period.

Given the extent to which the UK government concealed its role in the palace coup, the recipients of these watches were and are unlikely to ever admit to playing that role.

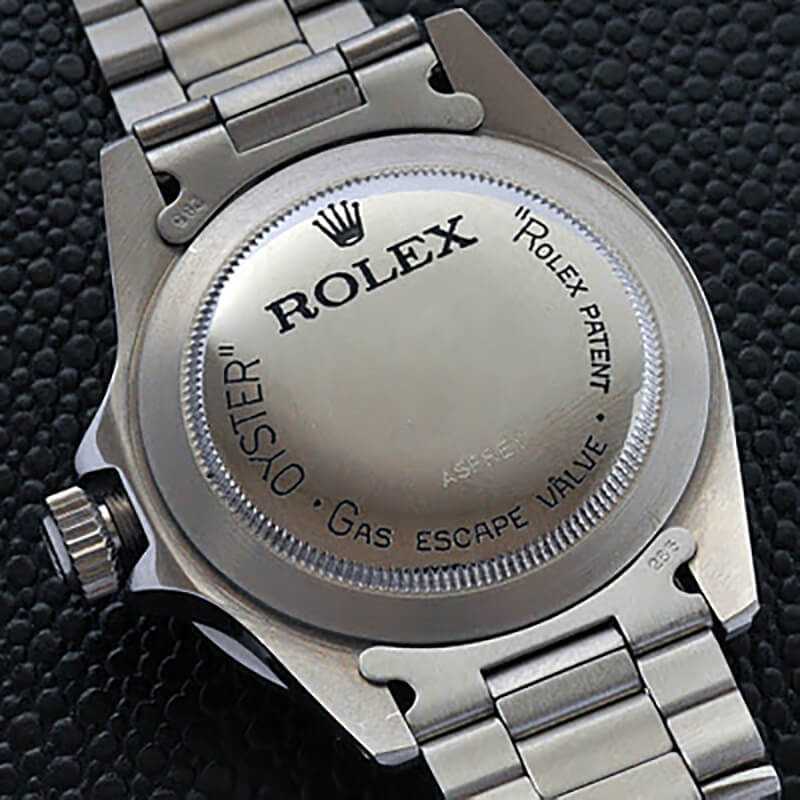

Back of a Red Rolex Khanjar Sea-Dweller from 1965 (photo courtesy www.vintage-db.com)

In any event, combinations of a demonstrably limited number of Rolex watches produced to order with special dials and presented to war heroes by an Arabian sultan is a heady mix making for a perfect storm of collectability (Bourn is by his own description a “dealer in rare and important vintage watches”).

But would you want to own one?

Dark am I, yet lovely, daughters of Jerusalem.

Do not stare because I am dark, for the sun has gazed upon me.

My mother’s sons were angry with me; they made me a keeper of the vineyards, but my own vineyard I have neglected.

Song of Songs, 1:5, 6

In 1969 I was seven years old and lived with my parents in a brand-new house built in a small enclave built at Ras al Hamra, a few miles west of Muscat, for the employees of Petroleum Development Oman (PDO), the consortium set up to exploit Oman’s newly found oil reserves. Built on a rocky spur running down to the sea, an area subsequently identified by Italian archaeologists as the site of thriving mangrove swamps and hunter-fisherman settlements during Arabia’s pre-desertification era 6-10,000 years ago, as a potential target for the British-backed sultan’s political opponents the “camp” was enclosed at a discreet distance by a wire fence and security gates.

But one day while I was playing in the sand and gravel that served as a garden in front of our house, a herd of goats came cantering across our garden from the western side of the camp, hotly pursued by a little girl in a dirty ragged red dress carrying a stick.

She was probably only six or seven years old and would have lived in one of the desperately poor villages we passed on the way to Muscat consisting of huts whose walls and roofs were made of date palm branches.

When she saw me, she stopped in her tracks and stood looking at me for what seemed like an eternity. Her skin was darkly tanned but her tousled hair was bleached blonde by the sun, and her eyes were large and alert, scrutinizing me at length, both of us intruders in each other’s world. Eventually she set off in pursuit of her goats.

During the four years we lived in Oman, this was the closest I ever came to meeting an Omani child.

First watch in Oman

I was watch-aware from an early age. My father took me to buy my first watch in Dubai when I was eight years old (Oman didn’t have watches for sale in those days, and certainly not for children); it was a manual-wind, steel-encased boys’ watch on a steel bracelet with a red second hand and luminous Mercedes hour and minute hands that lit up like Blackpool tower at night.

It fascinated me; in bed at night I would admire the tumor-inducing glow of the hands and indexes before laying it on my pillow to listen to it ticking.

I also learned the dynamics of “tropical” aging of a watch at a very young age. My best friend at the time was an English boy called Nigel, whom I held in great esteem because when I first met him in the departures lounge at Heathrow airport, he was wearing a Blue Peter badge.

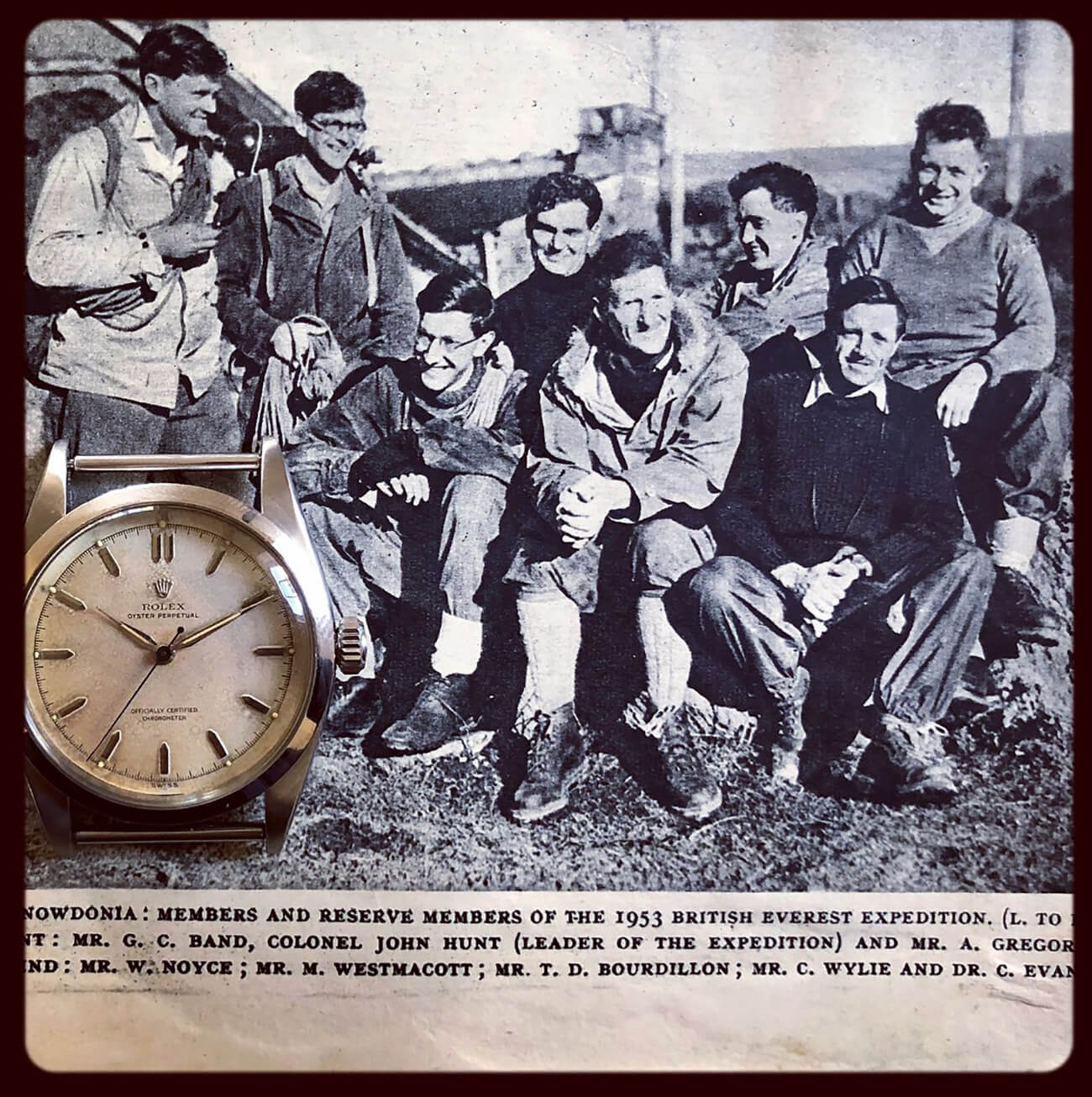

George Band with fellow Everest climbers on the 1953 Hillary/Tenzing expedition (photo courtesy Rolex Passion Report)

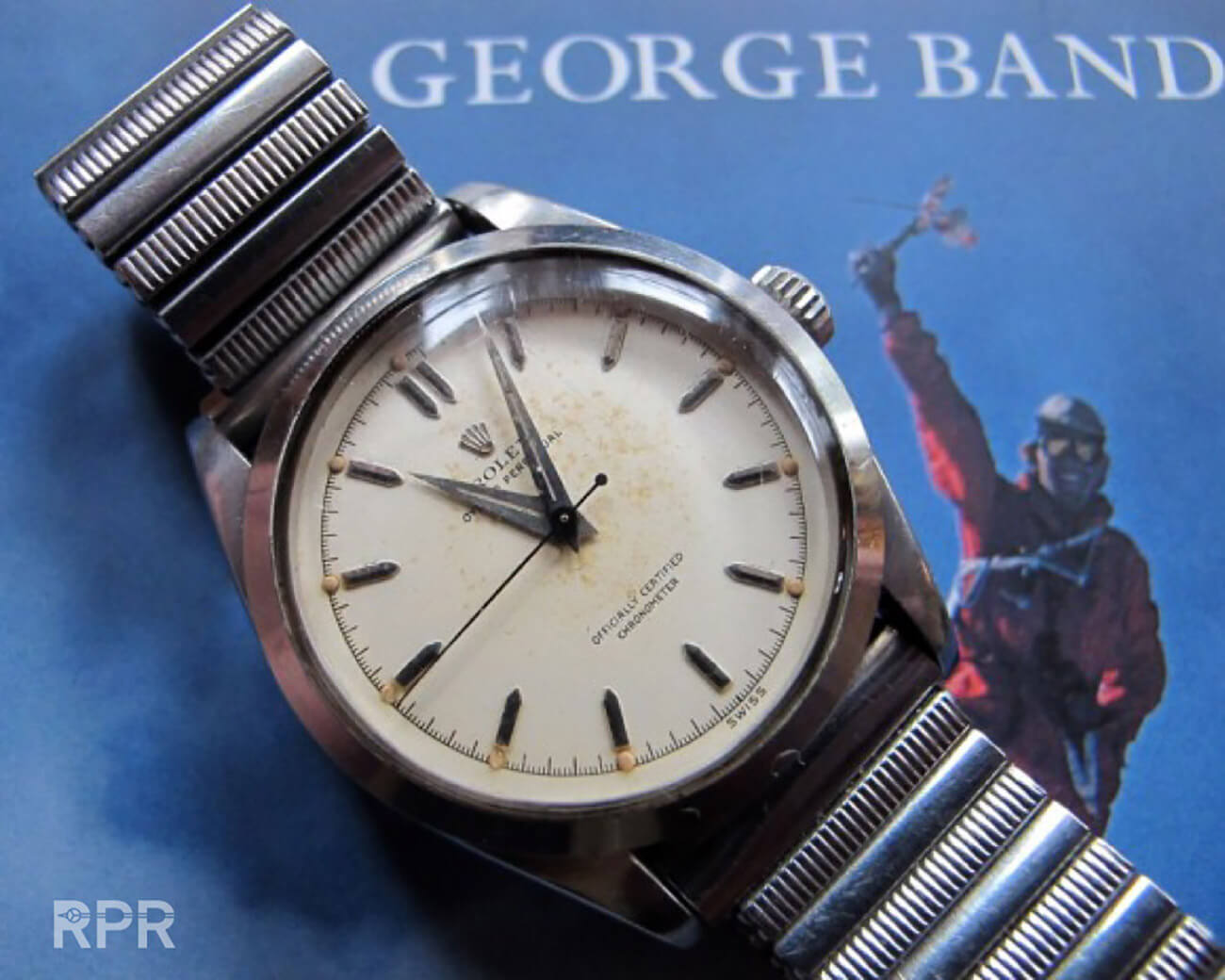

Almost as significant to me at the time, his father George Band had accompanied Edmund Hillary on the successful 1953 Mount Everest expedition (wearing a white-dial Oyster Perpetual like the rest of the team). Perhaps as a result we used to spend a lot of time climbing things – walls, roofs, in and out of wadis, whatever was available.

Rolex Oyster Perpetual worn by George Band on the 1953 Hillary/Tenzing expedition (photo courtesy Rolex Passion Report)

Once, after scaling a ten-foot partition wall by the patio to the rear of their house, Nigel let out a joyful shout and picked up a watch from the top of the baking hot wall. “So this is where I left it!” Several months of Omani sun and temperatures over 40 degrees Celsius had stripped the watch of its original color scheme since his previous ascent of the wall; I don’t remember whether it still worked.

Some Omani history

In her book Sultan in Oman, Jan Morris (who was James Morris at the time) describes an Omani tribesman with whom she was having tea in an oasis leaning over to inspect her watch, asking “is it a Longines”?

This demonstrates the level of watch brand awareness in mid-1950s Oman, probably due to Saudi influence, where the giving of prestige watches had become an established practice and an indicator of the recipient’s standing.

Morris’ watch was not a top-tier brand known to the tribesman, leaving him uncertain as to whether his knowledge of Swiss watch brands was inadequate and Morris was possibly a person of great importance, or Morris was merely a nobody with an unremarkable watch.

Britain’s role in Oman

As far as Oman is concerned, the British press has in general either simply not reported events or followed the official line of portraying the UK’s relationship with Oman as “friendly support,” providing resources military and otherwise for a “bloodless coup” and helping the current sultan embark on the long overdue reform and modernization of his country by helping him to depose his dreadful, despotic father.

While the latter is not in dispute, this is a very selective and misleading reading of history.

It attempts to portray Oman as being separate from and immune to the post-World War II upheaval whereby the United Nations rejected colonialism and the European powers withdrew from their African, Asian, and Arab colonial territories, sometimes voluntarily, sometimes at gunpoint, as in Algeria. Oman was “different,” although it was never explained how or why. Oman had no need for Algerian-style independence because it was an “independent sovereignty” already.

The insurgency in the mountainous Dhofar region to the south, which gathered strength throughout the 1960s and 70s and at times looked poised to undermine the new sultanate, was presented as a Soviet and Chinese-backed plot to lay claim to Oman’s oil, and therefore a threat to the UK’s interests that merited harsh military intervention. Only in 1972 did the Observer and Sunday Times newspapers dare to describe the conflict as “Britain’s secret war.”

A typical description of the situation in Oman at the time reads as follows:

“Oman itself was about as backward as any country could possibly be. It was poor and ruled by a sultan who was medieval in his attitude to progress. Despite the recent discovery of oil in commercial quantities, he was in no hurry to modernize his country. Outside of the capital Muscat, there were no roads, no hospitals, no schools, no electricity, no piped water and no authority other than the sultan. . . . In July 1970, the sultan’s son Qaboos bin Said ousted his father in a palace coup and declared himself ruler of Oman. This was a popular move and brought about immediate changes, as the new sultan was prepared to modernize his country.”

The reality was that Britain had run Oman as a de facto colony in all but name since the decline of Portuguese and then Ottoman influence in the 1870s, and had maintained the India-educated Sultan Taimur in power since 1932 by funding 50 percent of the country’s modest budget and continuing to do so until the the 1970s when oil revenues began to pour in.

Oman (1996 CIA map courtesy Wikipedia)

Strategic value of Oman

Situated on the Indian Ocean at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, Oman’s sole interest to Britain was as a strategic outpost on the way to India from where it could control shipping coming from the Gulf and later on via the Suez Canal, so living conditions for the population in this “protectorate” were of little concern to Whitehall.

In 1970, Oman had an infant mortality rate of 75 percent, and trachoma, venereal disease, and malnutrition were widespread. There were only three schools, the literacy rate was five percent, and there were only six miles of paved roads. Given that its army officers and “political agents” occupied all but one of the senior military and administrative posts in Muscat and Oman, this was an appalling situation for which Britain was almost entirely responsible.

More significantly, the war in Dhofar was more than British-backed: British soldiers and “contract officers” (mercenaries) actually did much of the fighting, using “scorched earth” techniques similar to those used in Vietnam, burning and destroying villages suspected of having rebel sympathies as part of a “hearts and minds” strategy.

One officer is quoted as saying, “We burnt down rebel villages and shot their goats and cows . . . Any enemy corpses we recovered were propped up in the Salalah souk as a salutary lesson to any would-be freedom fighters.”

UK academic and writer Fred Halliday managed to visit the Dhofar region during the fighting in 1972 and reported in his book Arabia Without Sultans: “The greatest difficulty caused by the new counter-revolutionary strategy was the suffering inflicted on the population. Everybody one met had lost animals in the recent fighting, and many had lost members of their family . . . the economic blockade had let to intense malnutrition, especially in the east and in the center as a result of the cutting off of imports from the coast and the systematic SOAF burning of crops at harvest time…such developments only confirmed the people in their hatred of the British and the Sultan . . .”.

Britain’s responsibility

To sum up, while press and media reports and articles of the time describe Sultan Qaboos’ removal of his despotic father as an honorable venture that merited Britain’s full moral, logistical, and military support, the greater picture has always been that it was only necessary because Britain had kept Taimur in power for so long.

And the only reason it had finally been motivated to do something about it was that Taimur was increasingly becoming an obstacle to the extraction of Oman’s oil reserves – by PDO, a consortium eventually dominated by Shell, a Netherlands/British-owned company. The subsequent Dhofar rebellion and its suppression were a war much like any other war, with atrocities perpetrated on both sides.

However, Britain’s continuing control over the country made it possible to completely block press access to the war zone, thereby controlling information that only became public knowledge at a much later date.

Last bastion of slavery

According to Guardian journalist Ian Cobain, until 1970 “Oman was the last country on earth where slavery remained legal. The sultan owned around 500 slaves. An estimated 150 of them were women, whom he kept at his palace at Salalah; a number of his male slaves were said to have been physically deformed by the cruelties they had suffered.”

The fact the new sultan continued to order Rolexes and other watches via Asprey in London, rather than directly from the manufacturer, merely confirms the grip that Britain continued to exert over the country.

Where does this leave watch collectors and their highly sought-after Omani Rolexes?

These watches are generally presented by Rolex dealers and enthusiasts as romantic mementos of a bygone era, awarded to unsung military heroes for acts of bravery by the progressive sultan of one of the more liberal Arab countries.

According to Halliday in the same book, the official British line expressed in a 1970 Defense White Paper (at a time when Secretary of State for Defense Ian Gilmour was very reluctant to give out information on the conflict) was that “The Sultan of Muscat’s armed forces, most of whose officers are British, have continued to be engaged in operations against the Dhofar rebels in the rugged hill country north of Salalah. The Sultan has made awards for bravery to some British officers for their conduct in these operations.”

Presumably some of these awards included watches produced to order by Rolex via Asprey in London with the Omani khanjar on the dial. Some of these watches may indeed constitute recognition of the bravery in combat of British soldiers (and to a significant degree, mercenaries) that went unacknowledged for many years by the British government as it was reluctant to be seen to decorate military staff who were supposedly there in a purely “advisory” role.

As a former resident of Oman in the late 1960s and early 1970s, I am the first to recognize that my family’s safety was guaranteed during that period by the presence of the British military, both in the Muscat region and at Natih and Fahud in the interior where the oil platforms stood.

However, these watches also represent a less appealing aspect of the country’s history: namely Britain’s share of responsibility for the country’s complete failure to develop economically and socially from the nineteenth century until the 1970s, and the consequent suffering of the indigenous population due to the lack of education and healthcare, poor nutrition, and military conflict.

Sometimes desirable artifacts come with uncomfortable or even unpalatable cultural and historical truths. A summary check of the various watch dealing websites reveals that a nice red “Qaboos” Submariner with patina’d hands and indexes is currently available, but “price on request” – a popular euphemism for “if you have to ask, you can’t afford it.”

Perhaps one day I will have the means to acquire one, but if I do the red signature will always remind me of the little girl in the ragged red dress.

Quick Facts Rolex Sea-Dweller Reference 1665 Red Khanjar/Qaboos

Case: 40 x 17.7 mm, stainless steel with helium escape valve

Dial: Omani Khanjar or Qaboos signature in bright red instead of “double red” lines, tritium-filled hands and markers

Movement: automatic Rolex Caliber 1570, 26 jewels, officially certified C.O.S.C. chronometers

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; date

Years of manufacture: early 1970s

* This article was first published on December 5, 2019 at Khanjar And Qaboos Rolexes: Are They The Vintage Watch Industry’s Blood Diamonds?

You may also enjoy:

Mythbusting: 3 Persistent Patek Philippe And Rolex Myths Debunked

Tracing The History Of My Grandfather’s Pocket Watch And Delving Into English Watchmaking

Gerontohorologyphobia: A Young Man’s Fear Of Being Seen Wearing An Old Man’s Watch

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!