Tim Mosso Builds a Custom Road Bike Part I: Who, Why, and What’s Involved in getting a Custom Fitted Bike

by Tim Mosso

Twelve years both isn’t and is a long time. It feels like a blink of the mind’s eye, but those years can take a fierce toll on all other parts of the body. As a road cyclist and runner with a raft of leg injuries, my first move was to ditch the running.

That helped, but less pain is still pain. My next move was to revisit my bike fit, and that led to a logical conclusion; it was time for a new bike.

This is a tale of two Tims. The other Tim in this story is Tim Gresh, a professional bike fitter in West Chester, Pennsylvania. As a former competitive cyclist with his own injury issues, Tim obtained a BA in Exercise Physiology after a life changing positive experience with targeted fitting solutions.

Since 2012, he’s owned and operatedGreshFit, a bike shop that manages the complete pipeline from fitting to ordering to building custom bicycles of all descriptions.

Tim Mosso’s old bike, a 2012 Bill Holland Exogrid

My old bike remains a good friend. It’s a 2012 Bill Holland Exogrid that was fit to me by Bill’s former pro cyclist and fit specialist Cody Stevenson in San Diego. I highly recommend Bill and Cody at Holland Cycles if you’re on the west coast and need a custom bike.

But the inevitability of follow-up fit adjustments and need to stay close to my office dictated a local solution. GreshFit was recommended by riders in a local group ride, and I was impressed enough to consult the shop’s online feedback.

Not only were the client reviews stellar, but many of them involved success with exactly the kind of lower back, wrist, and knee pain that was limiting my rides. Tim’s small but focused YouTube channel impressed with unique perspectives on fore-aft weight balance, crank length, hip dropping, and body asymmetry. Almost all of it applied to specific problems I was experiencing.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

Having pursued a decade’s worth of physical therapy, medications, various kinds of injections, ice packs, and rest, a new bike fit was the only unexplored avenue for relieving the worst of my discomfort.

Tim Gresh, founder of GreshFit bike fitters

After a few failures to launch, a fit appointment was made, and I paid a mid-January visit to GreshFit. Following introductions, Tim spent two hours leading me through efforts on a stationary trainer, positioning on my existing bike, flexibility tests, and evaluations of my current fit.

This is a good time to mention that GreshFit is an observational fitting studio. While it sounds self-evident that a bike fit would involve a supervisor “observing” a rider, primary reliance on firsthand observation is something distinct.

Since the 2000s, bike fit studios have been overrun with technological gimmicks of varying value. Lasers, cameras, video playback, motion capture software, and computer analytics have promoted secondhand observation that leaves the fitter’s eye and judgement dependent on the output of an electronic filter.

Tim Mosso testing his balance on a bike

At best, this tech can supplement an experienced fitter’s expertise. At worst, it can be a crutch for deficits of understanding and skill. The less foundational experience a fitter brings to the job, the greater the likelihood that standardized tech will produce standardized solutions. In general, the best fit studios have less of this.

Frankly, I was relieved to see nothing but a turbo trainer and a virtual road screen inside of the fitting space.

Evaluating knee tracking for pedal width and shape

Tim spotted issues immediately. Viewed from behind, my knees were moving diagonally; vertical motion is ideal. Knee tracking corresponds directly to knee health, and mine had been declining for years. Special-order Speedplay pedals with dramatically longer 59mm spindles – up from my old 53mm – were selected.

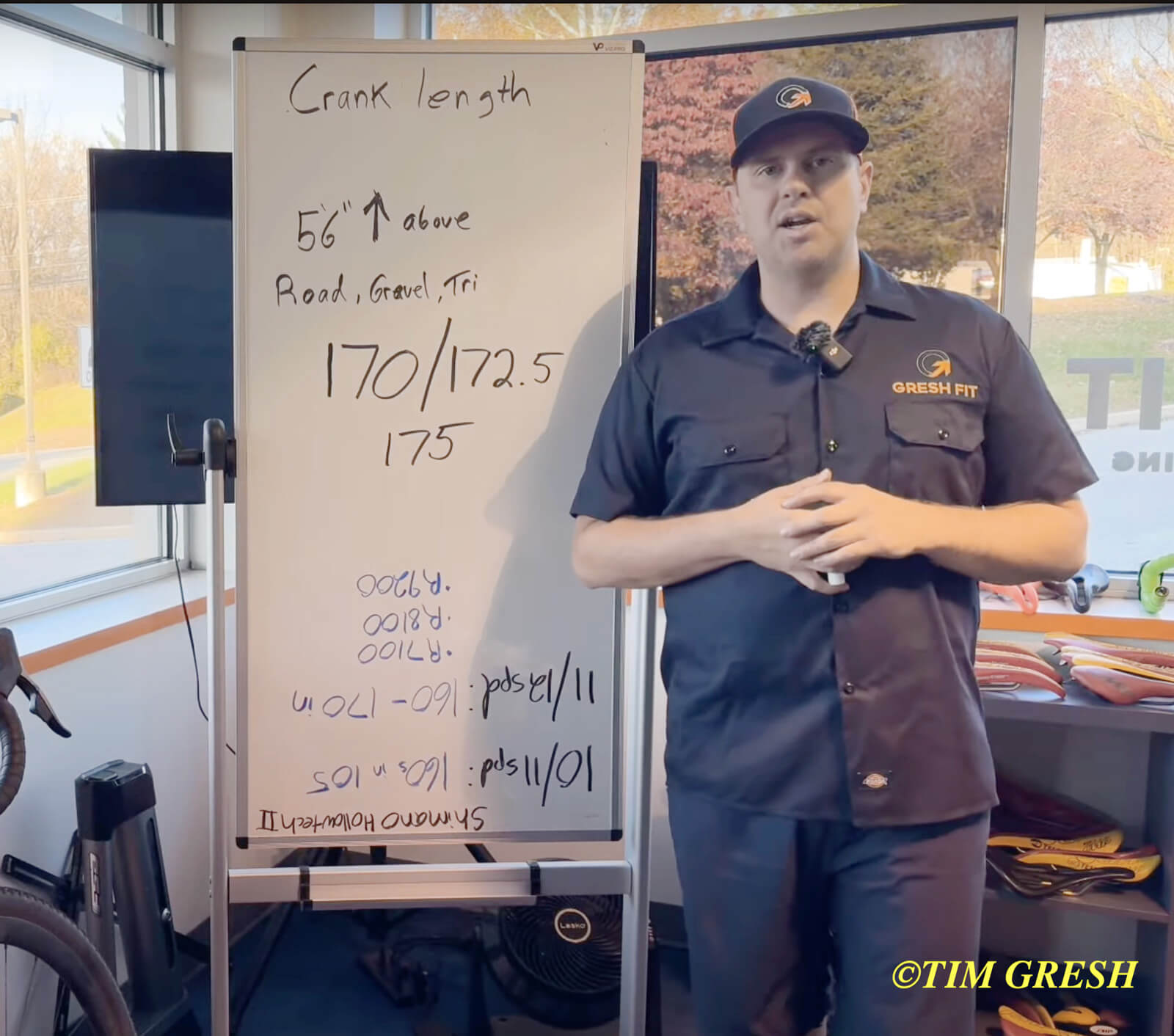

Evaluating pedal crank length

Knee flexion at the top and bottom of my pedal stroke was excessive; new crankarms of 165mm – down from 175mm – were specified. All of this helped to close my hips and remove potentially aggravating motion.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

After years of riding with my hands exclusively on the drops of the bars, it was time to rethink my riding position. Since the end of downtube shifters in the late 1980s, the customary riding stance of road cyclists has involved hands on the shifter hoods. Tim moved me upward and backward from my race-like forward tuck. Not only did this relieve the pressure on my wrists, but it reduced the strain on my lower back.

Previously, my wrists had been supporting my entire upper body; moving back let core muscles share the burden. In doing so, the small lower back muscles no longer needed to act as the sole bridge between my leg muscles and upper body.

Tim Mosso’s new riding position with hands on top of the bars

With the reduction in crank arm length, my pronounced toe-down pedal stroke became an agenda item. While useful for explosive efforts (e.g., racing), plunging extensions of the forefoot also increase knee flexion. Since race sprints have been off my radar for years, it made sense to pursue a flatter pedal stroke. Tim fit me to a new mid-foot cleat position to keep my shoes level at the upper and lower extremes of leg extension.

Pedal cleat positioning

A change in gearing was specified to replace high-torque efforts with lower-force efforts. Since my knee injuries, I’ve spent considerable time changing my pedaling style from low-RPM/high torque to high-RPM/low torque while raising sustained power.

But even with this move towards high pedal speed, I was locked into gearing biased towards slow turning.

A drivetrain change to a compact crankset (50-34) was specified to favor the 95-100 RPM average I maintain to preserve my creaky knees.

My previous bike had been designed with racing in mind. American style criterium racing involves mass starts on small circuits built in parking lots or around city blocks. It’s fast, explosive, and demands agility.

A bike built for this kind of riding will be sensitive to input, stiffly built, and only as stable as necessary to avoid tossing the rider. My old Exogrid – by my own request – had been designed this way. It was a sports car of a bike – a Corvette.

—————————————————————————————————–

Out with the old . . . Tim Mosso’s soon to be superseded Bill Holland Exogrid

The only problem is that I injured my knees through running shortly after taking delivery of the Exogrid in 2012. Racing – which involves violent acceleration and weight training of the legs – suddenly was off the agenda.

So, I focused on fitness, endurance, and fast group rides for over a decade; my old bike wasn’t built for that.

I realized that my Corvette really needed to be a Cadillac V-Series. Long-haul comfort and refinement demanded equal billing alongside raw performance.

Following two hours of watching, riding, and discussion, Tim and I had choices to make. First, we agreed on the overriding goal of relieving my assortment of acute and chronic pains. Second, we decided that a clean slate offered the best potential to address that challenge.

The second installment of my custom bike experience discusses the process of planning and building my bespoke frame – the core of the bike.

For more information, please visit https://greshfit.com/

You might also enjoy:

Tim Mosso Builds a Custom Road Bike Part 2: The Frame

Tim Mosso Builds a Custom Road Bike Part III: The Parts

Building a Custom Road Bike Part IV: The Ride

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Hi Tim!

Thanks to a fellow cyclist and Q&P contributor. I replaced a hip earlier this year. Subsequently, during my endurance rides I just didn’t feel right. Then I read your piece and it dawned on me that something has changed and just maybe I should get a refit on my bike. Without your article, I’d probably continue to suffer.

Best to you,

Chris

No Campy bikes?

I had a technical fitting done in the early 2000’s and it was one of the worst fitting bikes I had. This place is quite famous and expensive for fittings. Had to sell the frame and for a smaller and different geometry (Fondriest to Pegoretti) and replace the cranks from 172.5 to 170. Some sites offer bike fit calc’s and they say 172.5, but I never liked the way the spun.