Equipo Navazos No 85: A Surprisingly Different Sherry

by Ken Gargett

Regular readers will be aware that I am a great fan of quality sherry. For some, the mere mention of Sherry will bring a thrill; for others, rolling of the eyes and shaking of the head. It really is a love it or hate it style. And this one is something seriously different.

Regulars will also know that I often get material from various events put on by friends – these days, it is my best option to see many of the great old wines as the cost to source them now is simply prohibitive.

The latest such event was a Vosne Romanee Grand Cru lunch. The procedure is that we each dig through our ever-diminishing cellars to see what we can find. This time, some truly extraordinary gems, but as well as the theme, one or two of us will normally include a champagne or on rare occasions, a sherry, and then perhaps even a vintage port to conclude, to add to the event in addition to our contribution.

Equipo Navazos No 85

This time, I grabbed a Sherry from one of my absolute favorite producers, Equipo Navazos, their La Bota de Fino No 85 (although I believe that this one cannot technically be called Sherry – as we will explain). It was up against some stiff competition in the quality stakes with various Echezeaux, Richebourg, a Clos Parentoux and, most remarkably, a 1988 Henri Jayer Echezeaux in perfect condition, so it was going to have to perform well. That it would was never in doubt.

We have seen the story of Navazos before (see Equipo Navazos La Bota 65 Ron ‘Bota NO’: No Additives, No Coloring, No Sweeteners, No Aromatics, Unchillfiltered, And 98/100. Cheers!) but very quickly, it began with a couple of friends, Jesus Barquin, who is a criminology professor at the University of Granada, a great lover of Sherry and the co-author of “Sherry, Manzanilla and Montilla: A Guide to the Traditional Wines of Andalucía”, along with Peter Liem, better known for his work with champagne (it is just over a decade old now but it remains the essential work on Sherry), and Eduardo Ojeda, who is the technical director of Grupo Estevez, better known as Valdespino (and much more).

The pair were visiting cellars and tasting sherries, as one does, and while at the Ayala cellars, on a visit in 2005, came across a barrel of Amontillado that they loved, but which was surplus to Ayala’s requirements. It was not that it was not a superb Sherry, simply it had taken a direction that meant it was not in Ayala’s plans.

That happens, more often than you would imagine.

————————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

As Ayala had no plans for it, as it did not work in any of their blends, Barquin and Ojeda purchased the barrel and bottled 600 bottles. They shared them with friends, naming it “La Bota de Amontillado No 1” after the Edgar Allen Poe story. They number every release and are up to almost 130 – not all are sherries, as they have released a few spirits and vinegars.

Each release is very limited (and these days, not cheap to say the least), but once it is gone, it is gone.

The lucky friends who got hold of a bottle of No 1 quickly spread the word and soon there was serious demand for the pair to repeat the exercise. It took a few years before they turned it into a commercial operation. Every year, the pair find a few more barrels which they release.

They are simply not just some of the greatest Sherries I have ever enjoyed, they are some of the greatest wines.

All of which brings us to the curious bottle called No 85. It is described as a Fino Amontillado, which is something one does not expect to hear. Not only that, despite being a Fino, it is made from Pedro Ximenez and not the typical Palomino.

Most wine lovers think rich, concentrated and extremely sweet fortifieds when one mentions Pedro Ximenez, or PX as it is usually dubbed. In fairness, it usually is. PX is also crucial to the wonderful Spanish vinegars. And whisky lovers will be familiar with it as plenty of great whisky is finished in PX casks.

Of course, whether a grape gives a dry or sweet wine is down to the winemaking and fermentation processes. Some are much more suited to one style or another, others are very versatile. PX is showing some of that versatility here.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

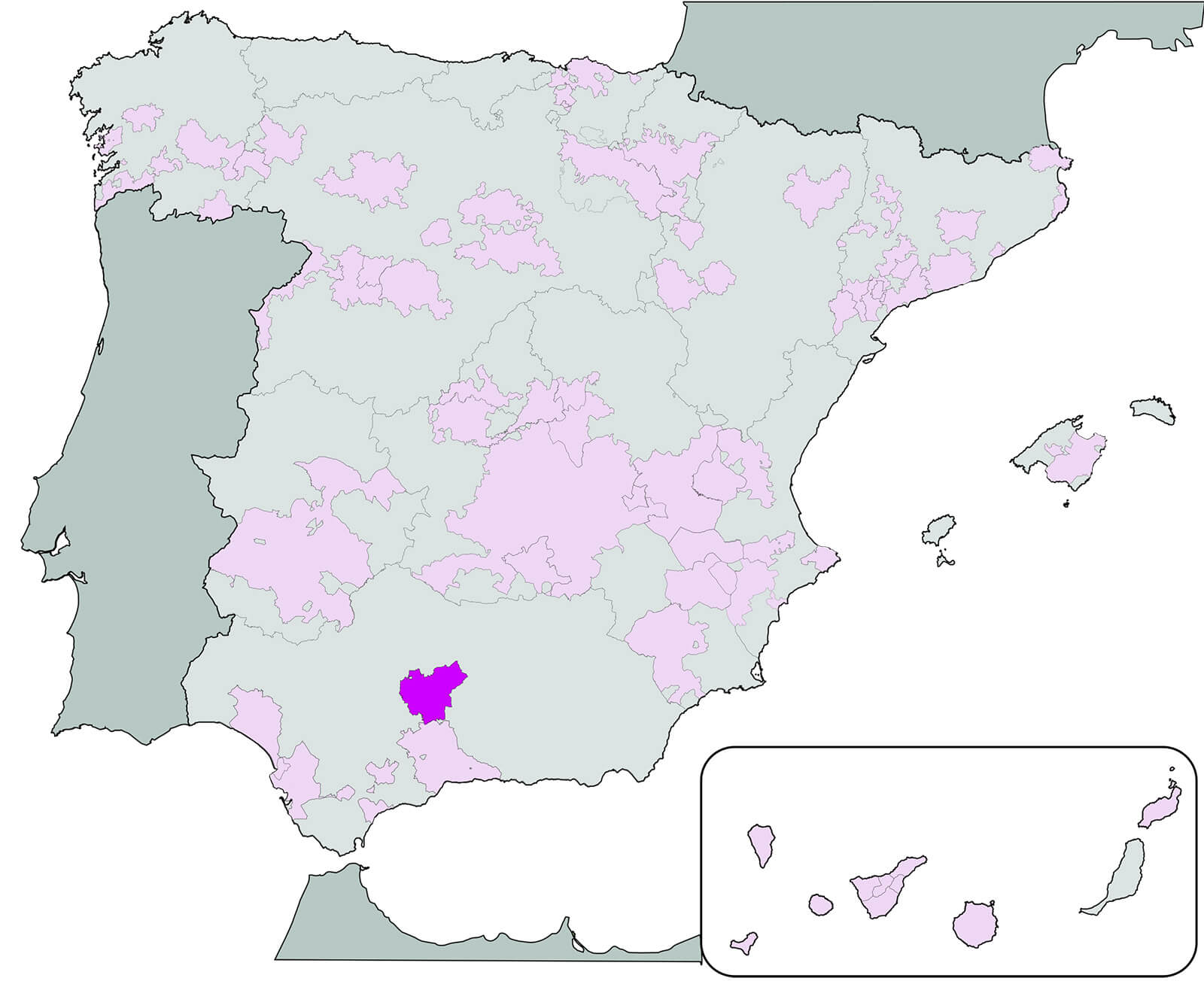

The reason we see a Fino from PX is because it hails from the third corner of the Jerez triangle (the designated region for producing Sherry and its ilk), Montilla-Moriles. This is from where those great and intense fortifieds made from PX come, but there is no reason that they can’t make other wines as well, though the public have not taken to them in the same way they have with their sweet wines and with the Sherries from other parts.

Montilla Moriles region in southern Spain (image courtesy Té y kriptonita/Wikipedia)

Montilla-Moriles often falls into the shadow of Jerez and Sanlucar, the other corners, especially when visiting the region. Ask any visitor to Jerez if they also made the effort to go to Montilla-Moriles and it is likely you’ll get a blank look.

If, however, you travel through Montilla-Moriles, you are every chance of seeing great swathes of grapes laid out in the sun on mats, drying and becoming ever more concentrated. It is impressive stuff. That said, beware, this is possibly the hottest wine region on the planet and temperatures can soar. But that is why PX is so successful.

Montilla-Moriles is an appellation on its own, not part of the classical Sherry Triangle (Jerez, Sanlúcar and El Puerto de Santa María).

Fortifieds from Montilla-Moriles usually cannot be named Sherry as the region is just outside the designated area, around 150 kilometers from Jerez, to the south of Córdoba, around the smaller towns of Montilla and Moriles (the rules are those as apply for the D.O. Jerez).

Although not called Sherry, they can be called Fino, Amontillado, Oloroso and of course, PX, if they fit the style. Almost all PX is grown around here (I think the actual figure is 95%). One point of interest – Amontillado originally means ‘Montilla-like’.

There are technical exceptions that allow PX from Montilla to be called Sherry, if the wine has spent at least two years in a bodega in Jerez. Production methods are effectively the same across both regions (close enough for our purposes).

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

At some stage, Montilla will have to find its own identity, especially in export markets. At the moment, it is seen as little more than a curiosity from the world of Sherry. It deserves better but it will have to work to achieve it.

The layer of flor under which Fino matures in Montilla is usually thinner than in Jerez/Sanlucar, as it is further from the sea and less humid. This leads to richer, fruiter styles. Occasionally, extra fortification is not required.

The heat of the region can see the degrees of alcohol reach levels that mean no fortification is necessary. In 2021, the Consejo Regulador of D.O. Jerez-Xérès-Sherry passed an amendment to allow for the production of unfortified Fino and Manzanilla.

Honestly, Sherry is like the proverbial onion. Every time one peels a layer, yet more is revealed.

The wines are incredibly versatile, from utterly bone dry to so densely sweet and concentrated that you’d swear a spoon could stand upright in a glass. The quality is so often enthralling and thrilling. There is no style of food, or even dish, of which I can think that a Sherry can’t be found to match it (one thought, if you are dining Japanese, the choice must surely be champagne or one of the lighter Sherries?).

The better ones are no longer the giveaway bargains they once were – and nor should they be – but they still represent amazing value.

So, back to No 85. It was released in 2018 and has been in my cellar ever since, until last weekend, at least. Jesus tells me that the first withdrawal and release of this was No 45, back in 2013, and that either very recently or very soon, the third of these, No 124, will hit the shelves.

Checking records, I suspect that this was also the source for their No 24.

—————————————————————————————————–

—————————————————————————————————–

The team talk of it as a Fino Amontillado, but this designation, around for centuries, has now been banned by the bureaucrats apparently with the intention of preventing consumer confusion. Good luck with that. I came out of all this very confused.

Equipo Navazos No 85

Basically, it is a Fino which has begun the journey towards Amontillado (think the caterpillar of Fino becoming the butterfly of Amontillado, although one should never demean Fino). The team look for aged Fino notes before they bottle. The flor will have started to fade.

It comes from the oldest Fino solera at the Bodega Los Amigos de Pérez Barquero in Montilla-Moriles. Jesus very kindly arranged a visit to Pérez Barquero for me a few years back and it was a wonderful experience.

The average age of the material bottled is twelve to fourteen years. Around 2,800 to 3,000 bottles made, depending on which source one quotes.

For me, an absolute privilege to drink a wine like this. I could hardly have loved it more. Such depth and complexity, with an incredibly long and lingering finish. Hazelnuts and almonds, a hint of an ocean breeze/saline touch, orange rind notes, florals, aged balsamic vinegar, tobacco leaves and teak.

Such a seductive texture. I gave it 97-98, but that it probably immaterial as if it is not in your cellar, the chances of locating a bottle are slim. Console yourself with the fact that there are so many stunning bottles of Sherry just waiting for you.

Every time I drink a wine like this I wonder why on earth am I not on the next plane to Spain.

For more information, please visit www.equiponavazos.com/en/

You might also enjoy:

Palo Cortado Sherry: An Accidental but Glorious Wine

Sherry Vinegar: A Truly Wonderful Indulgence for Your Kitchen

Primer On The Most Divisive Of All Wines: Sherry

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!