As unbelievable as this may sound, scientific progress and athletic excellence usually go hand in hand. As technology advances, athletes receive assets to train harder and smarter with the best in new and novel equipment available.

These circumstances allow for world records to be broken, nay, shattered at ever faster paces, with athletes at times even seeming super human. This becomes most evident every two years when the largest and most prestigious global event commences: the Olympic Games.

For these next two weeks, Sochi, Russia will showcase the best athletes from around the globe as the host of the winter Olympics. What this country brings to the table is a long history of athletic prowess and technological ingenuity that many may forget about in the current geo-political climate.

Russia’s strong past includes birthing Olympic champions and inventing rugged technology; this is surely due in part to the hardy population that makes up the largest country by square mileage in the world. In the last ten games alone, Russia has racked up 488 Olympic medals, second only to the United States with 631.

It’s clear that athleticism is not a foreign concept, and neither is technology, clearly seen in the country’s aviation and space technology throughout history. And, of course, there is also a strong – yet relatively unknown in the west, anyway – back story in watches. Check back on Thursday when we present you a more in-depth look at the history of Russian watchmaking.

As we direct our attention to Russia and to the many outstanding feats of physical prowess on display over the next fortnight, I think it is a great time to draw some parallels between what we will be seeing and how the country’s watch history relates to a certain few events. Presenting some milestones of Russian watchmaking and aviation and their Olympic counterparts.

A famed navigator of 1961

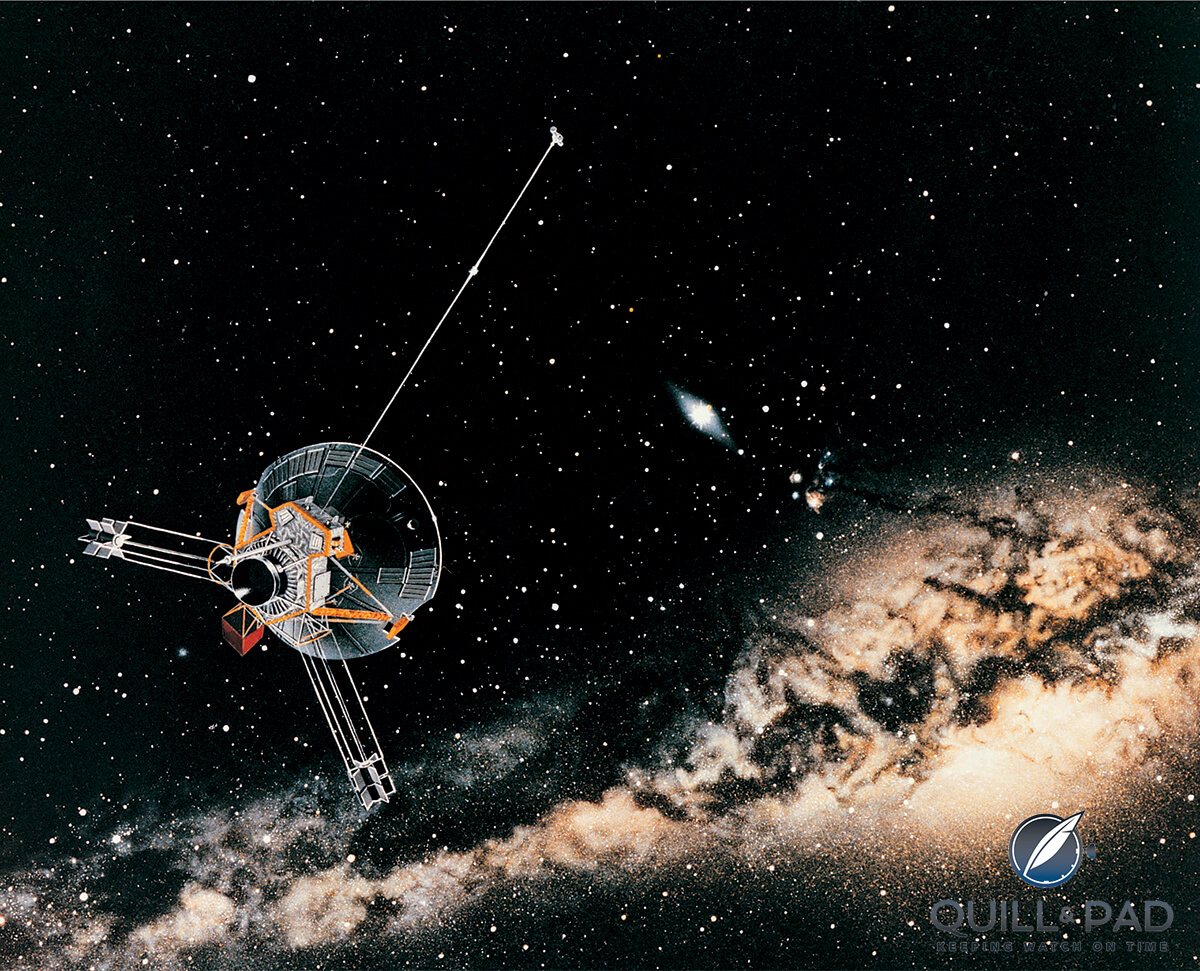

The first major milestone in Russian aviation (and for human spaceflight altogether) took place on April 12, 1961. The space race kicked off in earnest as Yuri Gagarin became the first human being to enter space and orbit the earth. To many modern observers, this may not seem to be a major technological feat.

These days, especially with the release of movies like Gravity, humans in space aren’t exactly breaking news unless that human is Sandra Bullock or George Clooney. It’s probably because there is always someone up there, either at the International Space Station, or launching every few weeks.

But when Gagarin successfully completed the flight in 1961, he made history for the entire world. He was the first, and that is something to celebrate.

Along for the ride on that flight was another Russian companion, though a less warm-blooded comrade: on Gagarin’s wrist was a standard-issue Russian pilot’s watch made by the First Moscow Watch Factory (FMWF). It was called Sturmanskie, which translates to “Navigator” (how appropriate), and contained a Russian-made movement.

So on that day, not only did Russia beat the Americans to space, they beat the Swiss as well!

That Sturmanskie was powered by the FMWF Pobeda K-26 movement, which was probably based on a movement from the defunct Dueber-Hampden Watch Company from Canton, Ohio. The equipment used to make it was bought and shipped to Russia around 1929 and the First Moscow Watch Factory was founded the next year originally under the name First State Watch Factory.

This watch was a simple, rugged, three-hand wristwatch that now has gone down in history as the first watch ever to orbit the earth. At least it was the first one to orbit our planet on a man’s wrist. I don’t know what weird things people may have put in early test flights or satellites.

Ski Jump

The historic flight and the watch that went along on it are perfect allegory for an Olympic winter games staple, the ski jumping competition. A fast and strenuous descent down a ramp (mirroring the rigorous rocket launch) gives way to a perfectly smooth and silent glide through the air (the vacuum of space).

In the silence, perfect angular momentum matched with a controlled fall is harnessed to provide a feeling of weightlessness. In my book, the ski jump is most like a quick trip to space out of any event at the winter games.

Quick trips to space

Gagarin’s quick trip to space had a profound effect on the world, Russia, and the First Moscow Watch Factory. Following further ventures into space and decades as the successful standard equipment for the Red Air Force, the FMWF was given a new name in 1964: Poljot, which means “flight.”

The following year, another major milestone happened for Russia and for watches that dreamed of being in space: on March 18, 1965, Alexey Leonov became the first human to conduct an extra-vehicular activity (EVA), which is more commonly known as a spacewalk.

The first human to be exposed to the vacuum of space, Leonov spent 12 minutes and 9 seconds outside of the Voskhod 2 spacecraft. Sharing that honor with Leonov was his spacesuit and a Poljot Strela chronograph, which had replaced the Sturmanskie as standard issue for pilots of that time.

Again, it was not a special-issue watch for the mission, but the same sturdy hardware that all Russian pilots were wearing. The Poljot Strela housed a FMWF 3017 column-wheel chronograph movement based on the Venus 150 caliber. Basically, it was a tried-and-true movement, and it performed very well in its new home.

The time spent outside the spacecraft on a spacewalk is obviously a dangerous experience by anyone’s standards. Unencumbered by a shell of a craft, having nothing between you and the earth but your suit, just makes me think of how liberating that feeling must be, almost blissful, a weightless wonder.

Freestyle aerial skiing

Comparing this to just one event of the Olympics is hardly adequate, so I think we need two: freestyle aerial skiing and figure skating. With freestyle aerials, you have danger, speed, and the feeling of being launched into the wild blue yonder. But it happens so quickly, and in my view, violently with the twisting, turning, and flipping that while it captures the flight and the danger, it lacks the beauty required for a fully accurate comparison.

Figure skating

So I proffer up figure skating as the “soul” to the freestyle aerials’ “body.” The figure skater, especially the female figure skater, glides across the ice with eloquence and grace, only to be shot into the air for a perfectly angelic triple axel, landing like a bird on the tiniest of branches. In my mind, those two events combined come close to the experience of a space flight combined with a spacewalk…if only for the purposes of my meandering.

Standard issue pilots

Fast forward to the late 1970s when Poljot develops Caliber 3133 based upon the Valjoux 7734 cam lever chronograph. This becomes the new standard issue pilot’s watch and brings us to the third major milestone for Russian space exploration.

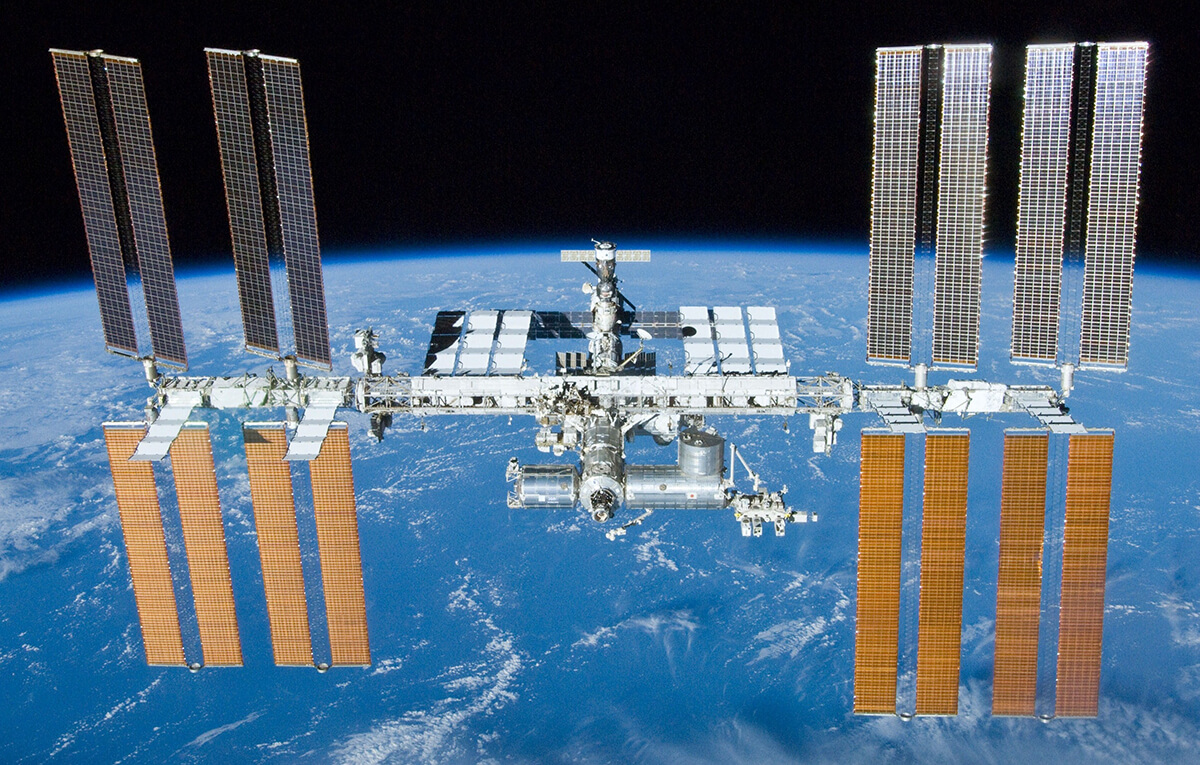

On January 8, 1994 Valeri Polyakov embarked upon a mission to the Mir space station, where he would stay as part of a study on the long-term effects of weightlessness in space. On March 22, 1995 – 437 days and 18 hours later – he returned to earth and set the current record for longest spaceflight for any single human in history.

With that flight, Polyakov proved that a human could physically survive and stay sane during extended space travel, and that the Poljot 3133 really was an excellent and robust movement capable of handling serious missions.

Nordic combined

Such an extended flight really reminds me of the word marathon. Of course in the winter Olympics, there are no marathons per se, but there is something that actually combines the experience of blasting into space and the long struggle against your body and nature. That event is something many people might not have even heard of, but it could be considered a good proxy for a long haul in space: the Nordic combined.

Say what? The Nordic combined is, as it sounds, two events rolled into one: the ski jump and a 10-kilometer cross country ski race. As previously mentioned, the launch of the jump takes up the first part of the space journey, and the long, tiresome race is the stand-in for the marathon stay that Polyakov endured.

There is no crowd to cheer you on, only your body, your skis, and the cold. I can’t imagine that being in the Mir or even now on the International Space Station is warm. If anything, it does its best to not be cold, but comfy or cozy is out of the question. So being aboard for 14 months in space might find its best allegory in the Nordic combined: a quick and exciting start with a long, slow finish.

And speaking of finishing, I want to speak quickly to an unknown quantity in both technology and watchmaking for Russia before I do. Prior to the space race, there was another race happening all across the world: the race to break the sound barrier. Debatably, America won that race, and slowly other countries added their names to the list.

The tenth person to be credited with breaking the sound barrier happens to be the first Russian to do it: not much is known about the flight or about I.E. Fedorov, the test pilot who was in the seat of the La-176 on December 26, 1948. This means we have no idea what watch was on his wrist, but we do have clues.

Based on things I have read and what I said earlier, the Sturmanskie with Pobeda K-26 movement was standard issue to all pilots by the FMWF, which should have begun being issued in 1947. So in December of 1948 I would venture that it is safe to say the first Russian watch to break the sound barrier MAY have been the same type of watch that was the first in space.

We can never know for sure, but I like the odds.

I trust this was a good intro to Russia and its technical history, and hopefully through these next two weeks we will learn some great things about watchmaking behind the previous Iron Curtain. What originally began in 1930, rugged people making rugged watches tested in the harshest of environments; what a grand heritage!

I love high-end watches (don’t we all?), but I can also appreciate purpose-built machines with a soul that do their job well without pretense or superfluousness.

Also, do turn your attention to Sochi and the wonderful athletes from across the globe coming together in peace for friendly competition. I know that some might be hesitant about supporting these games based on social issues, but let’s look past that for now and cheer for the spirit of competition and international cooperation.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] We have reported on individual watchmakers and their oeuvres; we have reported on the doings of big groups; and we have reported on horological topics surrounding major events such as the FIFA World Cup and the Olympics. […]

[…] – Joshua’s fanciful look at the ingenuity of the Russian culture in terms of watches, space travel and Olympic sports. […]

[…] Joshua’s fanciful look at the ingenuity of the Russian culture in terms of watches, space travel and Olympic sports – Elizabeth’s short history of Omega’s involvement in Olympic timing – A look at the equipment […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!