by Ian Skellern

In 2009, Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey were considering a number of options for what had become a quest to transmit and safeguard traditional watchmaking knowledge and experience for the next generation.

One was to help somebody working internally at Greubel Forsey to create a watch from scratch – with the additional aim of broadening and deepening his or her knowledge.

It was just one of many ideas the pair was juggling, and it still needed more reflection and time to mature. Which was just as well because Robert Greubel, Stephen Forsey, and Philippe Dufour were also ready to launch the Le Garde Temps – Naissance d’une Montre project (see The Le Garde Temps Project: A Horology Nerd’s Dream Come True) that year, which also had the aim of safeguarding and transmitting traditional watchmaking knowledge and experience to the next generation.

The early stages

While the Le Garde Temps project took up a lot of time and resources over the following years − and is still not quite finished yet (see A Hero’s Journey Begins And Ends: Naissance d’Une Montre, Le Garde Temps) − the concept of an internal project continued to advance. By 2012, it had advanced to the stage that the watch (like Le Garde Temps) would be traditional (after all, the basic idea was born of a desire to save traditional skills and knowledge) in the sense that it would have three hands and a large (in fact, an extremely large) balance wheel.

Greubel had made a sketch of how he thought the dial side would be laid out with an offset subdial for hours and minutes, a large-diameter balance wheel supported by a long balance bridge, and small seconds nestled up close to the hour/minute subdial.

And it had also been decided that Didier Cretin would be the man behind this first of a new “Signature” collection. Cretin has been with Greubel Forsey for 11 years and holds a position called “Responsable ADN Produit,” which means that he is responsible for ensuring the “DNA” (the golden design thread) of timepieces in the brand’s collection. Cretin is not only an excellent watchmaker, he is also a very skilled movement designer and has deep knowledge of the essential elements making for a superlative Greubel Forsey timepiece. As Cretin explains, “For Signature 1, I could use any design or technical element that we had already used at Greubel Forsey with the aim of developing the simplest traditional watch possible that was still 100 percent Greubel Forsey.”

Fly in the ointment: the large balance wheel is impossible

So now it is 2012, and Cretin is busy working out the myriad details and calculations that go into designing not just a completely new Greubel Forsey watch, but one with a completely new movement.

And this completely new movement with a very large-diameter flat balance wheel would also contain Greubel Forsey’s very first flat balance wheel.

The problem Cretin quickly discovered was that no balance wheel manufacturers were willing to even try making such a large balance wheel. While superficially simple, making a good − meaning perfect equilibrium − balance wheel is one of the most demanding watch components to manufacture because of the incredibly tight tolerances required.

And the difficulty in manufacturing a balance wheel increases exponentially as the diameter increases and the structure becomes much more susceptible to twisting. Imagine how much easier it is to twist or wobble a large-diameter hula hoop compared to a circle the size of a Frisbee.

A close look at the dial side of the Greubel Forsey Signature 1 by Didier Cretin; note how widely spaced those Geneva waves are

Why a large-diameter balance?

The isochronal (regular) oscillations of the balance (wheel and spring) are what determine the precision of a watch movement, but shocks can easily disturb the regularity of the oscillations as they can momentarily distort the shape of the hairspring and/or change the pressure and friction on the balance staff (axle).

Watchmakers have long known that the secret to making a good balance wheel is to have a maximum of inertia so that it would resist any sudden changes in rate. This was traditionally achieved by making the balance wheel as large a diameter as was practicable and as light as was practicable so that the mass was concentrated around the long perimeter.

But large-diameter balances are difficult to make; if too heavy they will require too much energy and they take up a lot of space. Large diameter balances also tend to be relatively slow beating: 2.5 Hz compared today’s ubiquitous 4 Hz balances.

Close look at the long flat polished bridge and complex flat in-house balance wheel of the Greubel Forsey Signature 1

Modern balance wheels tend to be smaller in diameter (8-9 mm) but beat faster to increase inertia. The idea is that while a modern fast-beat balance might be easier to disturb than a slowly moving large-diameter traditional balance, the perturbations should affect the balance for less time due to shorter-duration oscillations.

And while today’s small-diameter, fast-beating balances certainly do a good job, there is something magical and mesmerizing about gazing at a slowly beating, large-diameter balance wheel.

The aim for Signature 1 was to develop a movement with a 12.6 mm diameter balance wheel that would be as light as possible. But as Cretin couldn’t find anyone to make it, he concentrated on developing other aspects of the timepiece.

There was never any consideration for a plan B utilizing a smaller-diameter balance.

But we cannot really understand Signature 1 properly without knowing a little about its creator, so let’s take a look at Mr. Didier Cretin to see what makes him tick.

Didier Cretin explaining the development of Signature 1 with a surfeit of Greubel Forsey watches (though can there ever be too many?)

Didier Cretin

Cretin was born in 1969 in the Vallée de Joux, the cradle of complicated watchmaking in Switzerland. When he was young (7-12 years old) Cretin played a lot with Lego Technic; however like many (if not most) of us he had no idea what he wanted to do when he grew up.

But when he was 15 years old, a cousin studying to be a watchmaker at the technical college in Le Sentier convinced Cretin to attend an open day at his school. After seeing how raw metal bars were transformed into beautiful timepieces, he knew that’s what he wanted to do and enrolled immediately.

It was 1985 when Cretin began his studies to become a watchmaker, and Swiss mechanical watchmaking was still reeling from the devastation caused by the arrival of quartz watches. However, by the time he graduated, things were picking up; even before graduating he was offered – and had accepted – a position at Breguet.

Cretin spent 11 years at Breguet, where he developed the not-always-appreciated-by-his-colleagues habit of developing tools and techniques for saving time and working more efficiently. And he was heavily involved in the development of Breguet’s equation of time watch.

When Breguet was bought by the Swatch Group in 1999, Cretin thought that it was time to move on and next accepted a position with Audemars Piguet. Here he worked in after-sales service learning how movements age and wear over time. But more importantly, Cretin was offered the chance to study to become a movement designer.

He knew at this stage that what he really enjoyed was the process of creation – and for a watchmaker, creation doesn’t get much better than designing movements.

Cretin left Audemars Piguet in 2006 to work with Philippe Dufour on a project for 18 months, and while there met Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey. He then began discussions with Greubel and Forsey – who quickly recoginized Cretin’s talent – about developing a Vallée de Joux outpost for then still nascent Greubel Forsey brand (Greubel Forsey launched in 2004). However, in 2007 he decided to move from the Vallée de Joux to La Chaux-de-Fonds and work for Greubel Forsey in the factory.

The tall tripod bridge supporting the hands of the Greubel Forsey Double Tourbillon Technique was Cretin’s idea

Cretin’s first project for Greubel Forsey was to develop the Double Tourbillon Asymétrique in a small series of eight pieces for the U.S. market. Another project was the development of one of my favorite watches of all time: the Greubel Forsey Double Tourbillon Technique (DTT). If you look closely, you will be able to recognize elements from the DTT in Signature 1.

A tripod bridge is also visible on the back of the Greubel Forsey Double Tourbillon Technique, where it supports the differential driving the power reserve indicator

The basics of Signature 1

When Cretin sat down with Robert Greubel to discuss him developing Signature 1, this is how the project was roughly defined: it would be a traditionally-inspired wristwatch; the basic dial-side layout was drawn by Greubel to feature off center hours and minutes on a subdial and a large-diameter flat balance supported by a long balance bridge and small seconds tucked up against the hours/minutes subdial. Cretin also confided, “I wanted some mystery as how the small seconds were attached to the movement.” And I think that he achieved that goal quite admirably.

Cretin worked with Greubel and a designer to perfect the aesthetics of the dial-side elements, but interestingly the back of the movement remained his personal playground.

As no external balance wheel manufacturer was willing to fabricate a balance to Greubel Forsey specifications as large as 12.6 mm, Cretin decided that it would have to be done in-house. Fortunately, having worked with the brand for nearly a decade by this time, he was well aware of the skills available at Greubel Forsey and was quietly confident that the team would have no trouble making the brand’s first in-house balance wheel despite the fact that the diameter required was deemed to be too large for even very experienced suppliers. It may be a flat balance, but it’s an extremely complex flat balance wheel

The apparent setback in not finding somebody to make the balance actually became one of the project’s big successes as a new generation of machinists at Greubel Forsey had now acquired knowledge that was at risk of disappearing: making a high-quality, large-diameter balance wheel. “The main problem was the balance,” Cretin explained. “We researched that for years but nobody could make the balance that we wanted to a high enough standard. So we decided to make it ourselves.”

The reason that the large balance was so important for this timepiece is that all Greubel Forsey movements have the common thread of improving chronometric performance. To date the brand has achieved this by developing a variety of regulators (balance and escapement) of various levels of complexity, including dual inclined balances, single inclined tourbillons, double inclined tourbillons, and quadruple inclined tourbillons.

Signature 1 may feature a traditional single flat balance, but it would be the highest performance flat balance that the brand could possibly create. Cretin’s name was on this watch and he wasn’t going to settle for anything less than excellence.

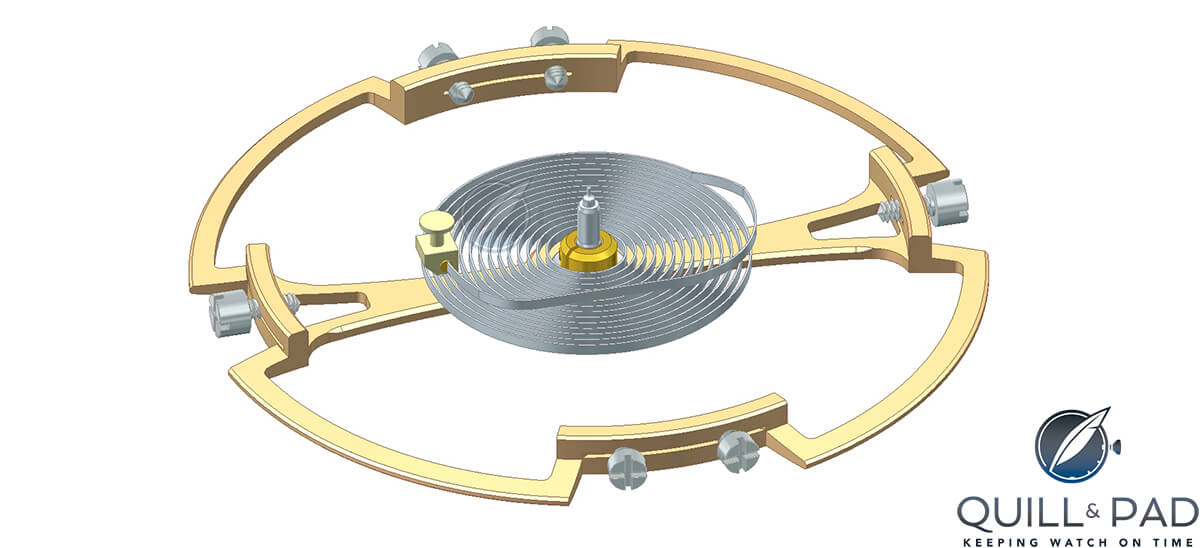

In-house 12.6 mm balance of the Greubel Forsey Signature 1: note the long slots through the screw holes to ensure that the screws impart no tension or possible distortion in the wheel metal

The massive in-house 12.6 mm diameter balance wheel features an L-shape profile construction to maximize the rigidity of the wheel and it features variable inertia with six gold mean-time regulation screws.

While it will probably be the large mirror-polished balance bridge that first attracts the observer’s eye to the dial side – especially as its scintillations contrast strongly over the dark, multi-level, frosted movement plate below – it is interesting to note that Cretin’s personal favorite detail on the front is that large flat-polished bevel on the Geneva wave-finished main plate on the top section.

I was confused at first as Cretin tried to enthuse me about what looked like impeccably executed anglage because I take impeccably executed anglage as a given at Greubel Forsey.

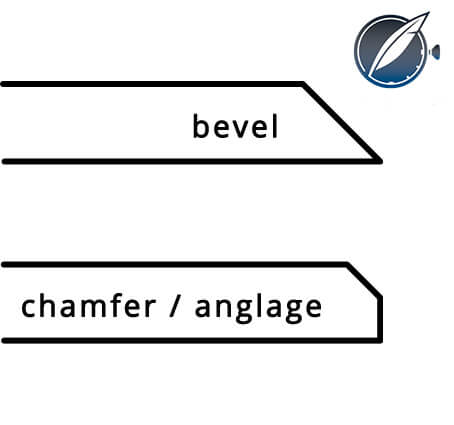

But here is why that shiny flank is likely to impress watchmakers more than watch aficionados. Anglage is a highly polished chamfer, but for all of the difficulty in executing consistent superlative anglage, all else being equal, chamfers (normal anglage) are relatively short compared to bevels (finishing nerds may enjoy Bevel and Chamfer: What’s the Difference).

While the words bevel and chamfer are often used interchangeably, the diagram above highlights the difference (illustrative only)

Highly polished anglage is usually a finish applied to steel bridges. Mirror polishing a large surface on a German silver main plate is much more difficult than polishing steel.

The Geneva waves have to be hand-applied absolutely perfectly. While it looks as through it has large undulating waves, the plate is actually quite flat − machined waves would be too deep as too much metal is removed. You will recognize this if you look at the edge between the surface at top and the polished chamfer: it’s a straight line rather than the wavy line you would expect.

You can actually see reflections of the balance bridge and its supports on the mirror polished flank of the main plate.

Other typical Greubel Forsey details to note dial side are the silvered solid gold dial, hand-finished sculptured hands, oversized gold chaton, mirror-polished screw heads and counter sinks, and, of course, that massive L-profile balance wheel.

So far, so Greubel Forsey. But let’s turn Signature 1 over and have a look at the back.

The case

It’s worth noting that at 41.4 mm in diameter and 11.7 mm in height, the case of Signature 1 is extremely comfortable, even on small wrists. And for the first time Greubel Forsey offers steel as a case option, but only as a “subscription” model where the client orders the watch directly from the brand.

View from the back

The view through the display back of Signature 1 offers a completely different vista to the front side. The plates and bridges all have Greubel Forsey’s typical difficult-to-execute frosted matte finish. It’s all extremely well done, but there is nothing that jumps out and screams “LOOK AT ME!” – nothing aside from the fact that this is still one of the world’s very finest movements, that is. And as Cretin reveals, “The front has input from Robert and the designers, but the back is 100 percent me.”

The movement side is Cretin’s playground, so let’s see how else he has imprinted his name on this movement – beside actually printing his name, that is.

View through the display back of the Greubel Forsey Signature 1 by Didier CretinFirst, there is that flattened tripod-shaped bridge supporting the spring barrel. Cretin first came up with the idea of this tripod-type support when he needed something very high and stable to hold the hands on the Double Tourbillon Technique. And he also used something similar on the back of the DTT as a bridge to support the spherical differential driving the power reserve indicator.

On Signature 1 Cretin used a similar tripod bridge to support the large spring barrel. But there appears to be something missing near that barrel: the click.

Close look at the click integrated into on arm of the spring barrel bridge of the Greubel Forsey Signature 1 by Didier Cretin

What, no click?

The click is a ratchet that stops the mainspring from unwinding whenever you wind the movement. Clicks can be quite elaborate as they are sometimes used by watchmakers and movement designers as a proxy for a signature. For Signature 1, Cretin developed what may well be the world’s very first spring barrel click that is integrated into the bridge. It is a very clever technical solution that is not obvious to the uninformed yet a micro-mechanical chef d’oeuvre to those in the know.

This is Greubel Forsey after all. Even though the click of Signature 1 is enclosed and largely hidden from view, it is still impeccably finished with snailing on the click wheel and ratchet. The ratchet teeth themselves are all beveled and polished.

But I do have one gripe: a watch called “Signature 1” from what is likely to form the basis of a new “Signature” collection and there’s no actual signature of the timepiece’s author on the watch itself? Come on, Greubel Forsey, a signature is much more than just a name – and this timepiece (and the following models) should be signed.

Unsurprisingly after a six-year gestation, Signature 1 looks to have met the project’s stated aims of developing a traditional timepiece that is as simple as possible while retaining everything that makes each Greubel Forsey so special. And it helps to safeguard and transmit skills to the next generation at the same time.

All in all, this is a beautifully designed and superlatively executed timepiece in which all of the essential elements are visible, but none clamor for attention.

Class doesn’t shout, it whispers. And I for one like what I’m hearing.

For more information, please visit www.greubelforsey.com/signature-1.

Quick Facts

Case: 41.4 x 11.7 mm, available in steel, white gold, red gold or platinum

Dial: silvered solid gold

Functions: hours, minutes, small seconds.Movement: Caliber GFS1, manually wound, 54-hour power reserve

Limitation: 66 pieces in total: 33 pieces in steel (subscription only), 11 pieces in gold (red or white), 11 pieces in platinum

Price: starting at 150,000 Swiss francs in steel, 170,000 Swiss francs in gold, and upon request for platinum

You might also find the following articles interesting:

The Le Garde Temps Project: A Horology Nerd’s Dream Come True

Le Garde Temps Project With Greubel Forsey And Philippe Dufour: Where It’s At And Where To Next

A Hero’s Journey Begins And Ends: Naissance d’Une Montre, Le Garde Temps

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] This rather special “tripod” click is positioned on top of the ratchet wheel and moves laterally outward as the crown is turned. It really has to be seen to be appreciated, so it’s particularly fortunate that Ian took the time to document it in Signature 1 By Greubel Forsey And Didier Cretin: Traditional In A Non-Traditional Way (And Check Out…. […]

[…] timepiece nor its most affordable − those two accolades go to the sublime Signature 1 (see Signature 1 By Greubel Forsey And Didier Cretin: Traditional In A Non-Traditional Way (And Check Out… − it has a traditional, though nevertheless extremely well thought out, regulator: there is no […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!