Quartz: Past, Present, But No Future?

by Martin Green

Nothing can stir up the watch world these days quite as much the launch of a new Apple watch.

Responses vary between placing an immediate order for one because it’s the latest must-have gadget to shrugging it off indifferently, “because it is not a watch.”

The smartwatch onslaught is a moment in time when the horological industry has taken to making a lot of references to that other calamitous moment (for mechanical movements) in history when the quartz watch was introduced. Back then, quartz watches took the world by storm, nearly destroying Swiss watchmaking in the process.

The evolution of Swiss quartz watches

There is one, big difference between the haute horlogerie industry’s reactions to the two potentially fatal events: while most traditional Swiss brands today have largely ignored the smartwatch, few brands ignored quartz.

Creating increasingly precise watches had been the collective aim of watchmakers long before Abraham-Louis Breguet had even thought about the tourbillon. At quartz’s time of development more than 50 years ago, quartz-regulated watches were just seen as a way of achieving a higher degree of precision.

Bulova Accutron

Electric watches and the famous Accutron with its tuning fork movement had already shown that there was great potential in embracing this technology. That didn’t mean that it wasn’t outside of the comfort zone of many manufacturers, 16 of which decided to join forces with Ebauches SA (a movement maker) to form Centre Electronique Horloger laboratories (CEH) in 1962. Based in Neuchâtel, it formed one-third of the beginnings of today’s CSEM.

Patek Philippe Beta 21 and advertisment (photo courtesy Atom Moore and Christie’s)

CEH was an attempt to at least keep up with all the research and development into electronic regulators in both the U.S. (the United States still had a sizable watch industry in those days) and Japan.

The result of these Swiss collaborative efforts was the Beta 21, the first prototypes of which were first shown in 1967. It was commercially introduced in 1970, just after Seiko launched its first quartz watch, the Astron.

The quartz crisis that very nearly doomed the Swiss watch industry wasn’t because the Swiss watch brands were caught off guard but because brands misread the future of quartz.

High-end watch companies thought that high-precision quartz regulators would feature in exclusive, beautifully finished movements that they could sell at a premium over mechanical movements, while the Japanese worked rather quickly to set up efficient production of low-priced quartz movements, allowing them to undercut the expensive Swiss watches.

Beta 21 design issues

It also didn’t help that the Beta 21 drove the design departments of many esteemed Swiss manufactures mad!

In the late 1960s elegance still ruled (see 60 Years Of Piaget Altiplano: Sophisticated Style Versus Fugitive Fashion), supported by refined, small, and slim mechanical movements.

The Beta 21 was none of that.

IWC Da Vinci Beta 21 from 1969

Rolex decided to forgo its signature Oyster case; Omega adopted a brick-like design for its watches housing the ungainly quartz movement; and Piaget made a stepped case with so many steps that it looked like it was attempting to reach heaven. Jaeger-LeCoultre never used the Beta 21 in a production watch, opting instead for the movement that Girard-Perregaux developed together with Motorola – not that this movement wasn’t any less chunky.

As quartz technology further developed, the Swiss were able to integrate it better and better into their collections.

After the Beta 21, Omega created an impressive range of quartz watches with interesting variations that even included the very first quartz watch to ever be awarded chronometer status (by Neuchâtel’s observatory, by the way); it is still considered one of the most accurate non thermo-compensated production watches ever made.

Girard-Perregaux developed some interesting complications for its quartz watches, and even Piaget became a full-blown manufacturer of quartz movements, making them smaller and thinner so they could be more easily integrated into the brand’s elegant watches.

Swiss quartz today

Today quartz watches are simply part of Swiss watchmaking.

Due to the renaissance of mechanical movements in the late 1980s and 1990s, quartz movements are now largely frowned upon by watch connoisseurs. Yet they have earned their place.

The Swatch watch arrived in 1983 and changed everything again

Swatch gets the credit for successfully reclaiming quartz for the Swiss by beating the Japanese at their own game: Swatch reduced the number of parts inside the quartz movement, thereby optimizing production, and put the movements in sharply designed, seasonal collections often sporting unique, if not outrageous, themes and selling the watches at very modest prices.

Breitling Emergency II from 2013

Over the years Breitling created several models that have became industry evergreens, among them the Aerospace and the Emergency, the latter even coming with its very own emergency beacon the wearer can pull out of the case in emergency situations.

F.P. Journe Elégante

Even François-Paul Journe, often and rightfully lauded as one of the best watchmakers alive, has created his own quartz movement; the quartz oscillator is nestled within his signature solid pink gold bridges (see Quartz Crush: F.P. Journe Élégante 48mm).

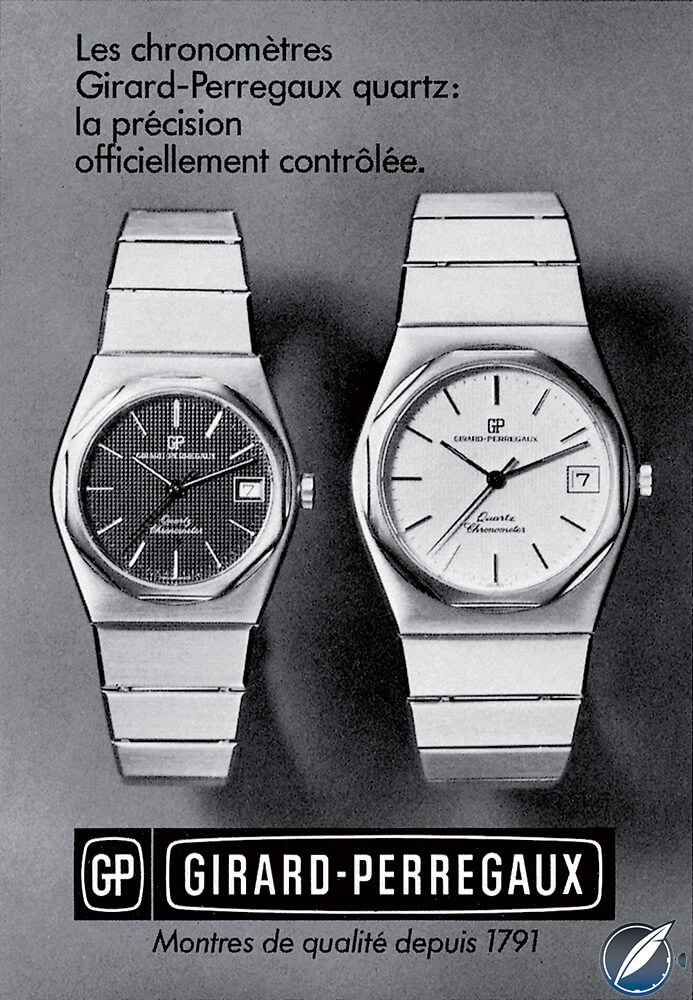

Advertisement for the original Girard-Perregaux Laureato Quartz

Another notable Swiss haute horlogerie quartz watch is Girard-Perregaux’s 2010 re-edition of the original quartz Laureato model issued in honor of the brand’s fortieth anniversary of GP quartz and 35 years of the Laureato line at the same time. It contained a very finely finished Girard-Perregaux-manufacture quartz movement.

A 2017 Girard-Perregaux Laureato 34 for women with a diamond-set bezel and a mechanical movement; the quartz is gone from the Laureato for the time being

The first Laureato was powered by Caliber 705, a modified version of the Girard-Perregaux 350 quartz movement developed in 1971. Caliber 705 represented a bridge between the quasi-experimental Beta 21 and the ensuing Swiss quartz. By 1975, Girard-Perregaux’s team had refined the brand’s in-house quartz movement so that it was thinner and more efficient. It was also certified as a chronometer. But perhaps most importantly, its frequency of 32,768 Hz has remained the universal gold standard ever since.

The future of quartz – or lack thereof

In a twist of irony seeing as quartz once almost sealed the fate of the mechanical movement, it now might be the smartwatch that kills the quartz watch as its first victim.

While the mechanical watch might not be as accurate as electronic quartz or the smartwatch, it claims an emotional bond based on traditional skills and crafts as well as the complexity of its movement.

Largely thanks to the advent of quartz movements, mechanical watches have become a form of luxury and even are even considered art. Apart from Journe’s Élégante creation, it is highly unlikely that the common quartz watch would experience the same destiny.

Samsung Gear S2 by De Grisogono

As more and more brands adopt the concept of the smartwatch, the quartz watch loses it edge – as happened with the electric watch and the Accutron before it. It might stand on equal footing in terms of precision, but it cannot compete with the vast array of additional functions that any smartwatch can offer.

The common quartz watch is likely to be outgunned and, especially as prices of smartwatches come down: for quartz watches, I predict a classic case of the hunter becoming the hunted.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] Um artigo que parte da história dos movimentos de quartzo no domínio da relojoaria para, por fim, questionar o atual momento que o quartzo está a viver. Basicamente, e até com alguma ironia, assim como o quartzo foi uma das grandes ameaças da relojoaria mecânica, será que os smartwatches serão a grande ameaça dos relógios de quartzo? É que, segundo o autor, os relógios mecânicos tendem a estar associados a uma componente emocional e não tanto a questões de funcionalidade e precisão – o mesmo não se poderá dizer dos relógios de quartzo. Para ler no Quill & Pad… […]

-

[…] Um artigo que parte da história dos movimentos de quartzo no domínio da relojoaria para, por fim, questionar o atual momento que o quartzo está a viver. Basicamente, e até com alguma ironia, assim como o quartzo foi uma das grandes ameaças da relojoaria mecânica, será que os smartwatches serão a grande ameaça dos relógios de quartzo? É que, segundo o autor, os relógios mecânicos tendem a estar associados a uma componente emocional e não tanto a questões de funcionalidade e precisão – o mesmo não se poderá dizer dos relógios de quartzo. Para ler no Quill & Pad… […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Having been a GP collector and watch nut for years I say great story. Insightful in its perspective of the watch history I grew up in and studied. Rings true on many levels. Quartz may evolve again to become a rare luxury niche

It would indeed be very cool if quartz became the niche that the Swiss expected it once to become. I do feel that there is room for that in the market.

The first thing the Swiss have to do is to perfect manufacturing. How can it be that an expensive Omega quartz watch is not able to land the second hand on the markers consistently? Look at Grand Seiko for an example of how to treat high end quartz. Maybe the Swiss can learn from the Japanese again?

A £50 Swatch can do it. Never buy a quartz watch which is shabbily constructed

Very interesting perspective and well written too.

Thanks

A very interesting read. It reminds me of the battle between smart phones and ‘dumb’ (or ‘feature’) phones. Like your average quartz watch, feature phones were once incredibly expensive one-trick ponies.

Manufacturing techniques improved, costs (and prices) came down and a couple of new features and upgrades were made, but when smart phones made their debut (and especially after Apple released the iPhone) many analysts saw the writing on the wall for the feature phone.

Some manufacturers persisted in making ‘high end’ feature phones for a while, but the mobile phone crown now rested firmly with smart technologies and feature phone were relegated to the role of emergency back-up, or were sold to the young, the elderly and the impoverished, for whom smart phones may be either inappropriate, unaffordable or inaccessible.

I can see quartz watches potentially entering this realm, though currently, of course, we are still seeing high-end, thermocompensated quartz coming from the likes of Omega, Grand Seiko, Citizen and Breitling, whilst Longines are soon to release their much-anticipated new version of the VHP. So if the analogy were to hold true we would should see greater uptake in smart watches correspond with the decision by the likes of Longines, Grand Seiko etc. to abandon quartz. Well, Rolex has already abandoned quartz, despite being one of the original Beta 21 players and producing the world’s first thermocompensated quartz watch. But they got out of the game in 2001, long before the advent of the smart watch. Omega’s potential departure may be more of a yardstick by which to measure the health of high-end quartz and they have been edging themselves out for a while, now, despite their impressive heritage in quartz development.

On the other hand, of course, ETA still churns out good-quality quartz movements, including thermocompensated, chronometer-grade lines that several brands use in nice, expensive watches, so I honestly don’t think we’re at the turning point for quartz just yet.

When electronic watches were replaced by tuning forks and tuning forks in turn replaced by quartz, there was nothing in either of the technologies that could redeem them, even for incredibly niche users. Quartz, on the other hand, still has a couple of tricks up its sleeve, including offordability, being able to function accurately, completely and reliably all by itself, and a battery life that stretches into years. There are, of course, a couple of smart watches now on the market that can operate independently of the phone, but price and battery life are still issues. Of those two, price is the more important. Going back to the mobile phone analogy for the final time, my old Nokia feature phone has a stand-by battery life of 30 days. The need to recharge smart phones every day was once cited as a barrier to their wider adoption. Until the battery problem was slicked (some analysts suggested), smart phones would never replace the feature phone. It turned out, of course, that people simply got into the habit of charging their phone every night. Some had probably already been in this habit, to begin with. And so it may well be for the smart watch. The idea that a 10-year battery life is meaningful in a world in which we are already accustomed to regularly charging our devices seems a little fanciful.

I will be hanging on to my quartz collection, though. I do have a smart watch but it mostly gathers dust. It just can’t compare to the ingenuity and craftsmanship of my old 1970s Omega or the fit and finish of my Grand Seiko.

Rolex indeed got out of the quartz watch game, but I heard rumors that they were working on a new quartz-powered perpetual calendar movement in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but also abandoned that. As the original Oysterquartz models were not the success the brand was hoping for, I don’t see quartz in their future, but like you so rightfully point out, brands like Omega, Grand Seiko, Citizen, and Breitling can for sure cater to the niche that will emerge.

I don’t think this author knows much about the watches bought by 98% of the population. Almost every single soldier, fireman and outdoor worker buys quartz. Casio have sold over 100 million G-Shocks, Cartier sell quartz by the bucketload because the simple fact is, very few people care about what’s inside.

Aren’t smartwatches still quartz watches at heart (i.e. the timekeeping method)?