by GaryG

It’s no secret: I’m an immense admirer of both Philippe Dufour, the horological artist, and Dufour, the person

I love his work and all that it represents (see Why Philippe Dufour Matters. And It’s Not A Secret).

Part of greatness, of course, is leaving a legacy; not only through one’s own works, but in the skills and inspiration passed on to those who follow. Dufour has done this very directly through the Naissance d’un Montre project with Greubel Forsey (see Le Garde Temps Project With Greubel Forsey And Philippe Dufour: Where It’s At And Where To Next).

And he has also provided advice to many of his colleagues on thorny challenges and helped to inspire Kari Voutilainen, among others, to launch their own independent watchmaking brands.

But who, if anyone, will history regard as the lineal heir to the Dufour tradition?

Having pondered it for quite a while, I’ve reached what at first may seem a counterintuitive conclusion: Romain Gauthier.

Why I might be wrong

I can already hear some of you shouting at the screen: “Hey, wait a minute: Gauthier isn’t even a watchmaker!”

Yes, that’s true: Romain Gauthier is not a watchmaker; he trained as a micro-mechanical engineer. And he spent his early career operating, and then supervising the use of, computer-guided milling machines used to make watch components, rather than restoring vintage watches or fulfilling an apprenticeship with a noted master watchmaker at one of the major maisons.

There are other differences as well: the second major part of Gauthier’s training was in management as an MBA student, while Dufour will freely admit that he is no businessman.

And while Dufour’s selection of a personal style for his watches was based in years spent disassembling and restoring classic watches and assessing the architecture and design choices made by their creators, Gauthier’s design approach is based on efficient utilization of gear ratios and direct transfer of power in the movement.

But if we look a little deeper, the critical similarities begin to emerge.

Why I am right

He’s a protégé: When Gauthier conceived of the idea of starting his own business and making his own watch, while doing his MBA he went to Dufour for advice. After three years of secret development, he “surprised” Dufour with his first watch, the HM, and gathered more valuable guidance.

Dufour also made key introductions within the industry and was quite keen, for instance, to organize a joint luncheon between Gauthier and our collector group during our 2010 visit to the Vallée de Joux.

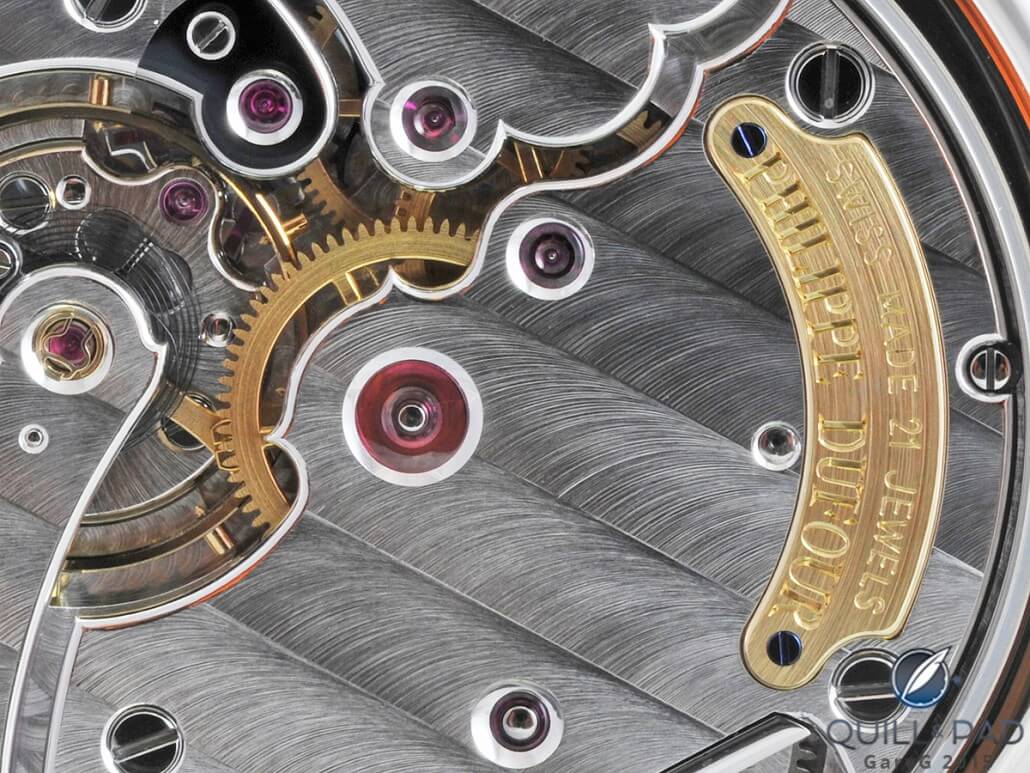

The Vallée de Joux: There are many styles and traditions of watchmaking, of course, including the movement design elements and decoration techniques used in the Vallée. Dufour and Gauthier are based within a stone’s throw of each other in Le Sentier, and it shows.

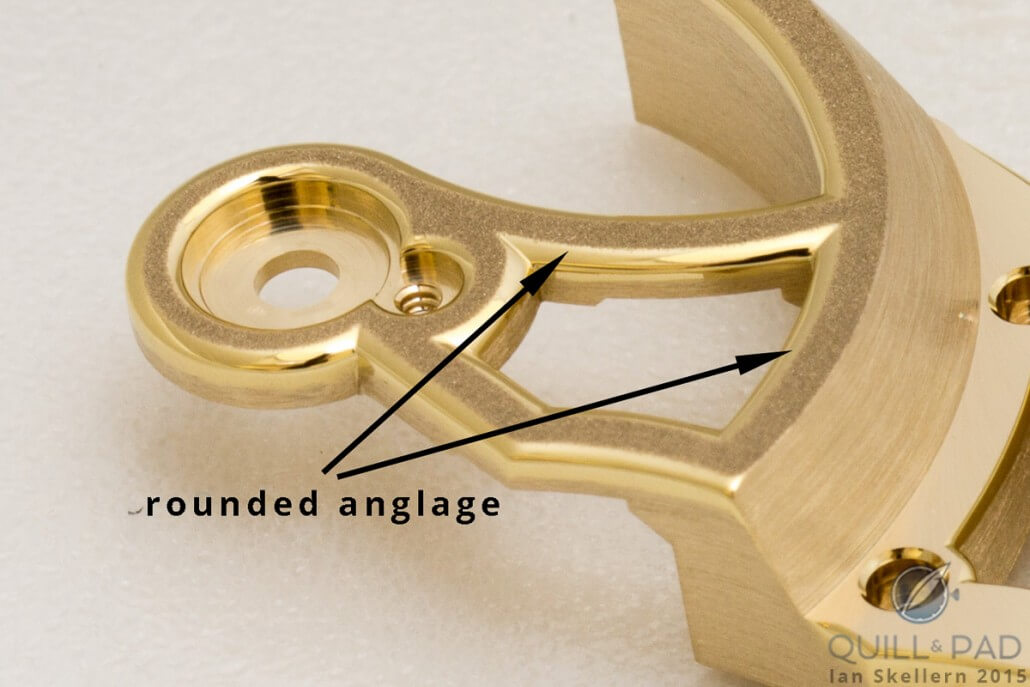

Vallée de Joux features such as the use of “finger” bridges are more evident in Gauthier’s first watch, the HM, than in the more recent Logical One. But finishing approaches, including the use of beautifully beveled, sharp interior angles, are in evidence across the board (see Why Do Ultra-High-End Watches Cost So Much? Hand-Finishing At Romain Gauthier Sheds Some Light).

Speaking of finishing: Dufour is, of course, the acknowledged master of the art, and when Gauthier showed him the prototype of the HM, he provided critically important advice on how to improve the finishing work to the highest standards.

There are only around four brands fine finishing using rounded anglage because it is extremely time consuming: Romain Gauthier and Philippe Dufour are two of them

At the same time, Gauthier has followed his own convictions on the use of hand-finishing and machine techniques. For instance, he strongly believes that it is important to impart the mirror finish on the chain of the Logical One using mechanical techniques, as hand-finishing would result in dimensional irregularities that would weaken the chain.

Clear and simple style: With Dufour, it’s the Simplicity, the most elegant execution of a three-handed watch I know. With Gauthier it’s the “small s” simplicity in that he seeks the cleanest technical approach for a given task.

For instance, in the Logical One Gauthier arrays the timekeeping elements on the right side and the constant force mechanism on the left, allowing for the most direct transfer of power. This is a philosophy also reflected in the use of a single-level chain and snail for the constant-torque and the button-driven, horizontal winding mechanism.

And while the dial and case styles of Gauthier’s pieces are perhaps a bit more ornate than Dufour’s, they do reflect a classicism missing in much modern watch design.

Self-branding: Obvious, perhaps, but very important: Dufour was among the very early leaders in the revitalization of true, self-branded independent watchmaking. Gauthier took the plunge early on with the establishment of his own brand and business.

His MBA project? The establishment of a watchmaking enterprise named “Romain Gauthier.”

Application of technology: When you hear Dufour tell his story, one of the most striking elements is the central role that technology played in his success. He was one of the earliest users of computer-aided design (CAD) in watchmaking, and also applies computer-guided machining (CNC), spark erosion, and other “high-tech” manufacturing techniques.

Gauthier has gone a step further: night and weekend access to CAM (computer-aided manufacturing) facilities was a critical enabler of his early success. His watches are a fascinating blend of fine handwork and machining – sometimes in areas one wouldn’t expect, as in the application of completely uniform striping to the surfaces of some plates and bridges.

A focus on timekeeping: The Duality, with its twin escapements linked by a differential, is gorgeous testimony to Dufour’s belief in the importance of great timekeeping. I can also testify that he took great satisfaction in hearing that over the period of a month of continuous use, my Simplicity gained a grand total of seven seconds!

With its chain-and-snail constant torque system, Gauthier’s Logical One brings another fresh approach with outstanding results: going from a fully wound to fully exhausted mainspring, its time loss due to isochronism is a miniscule four seconds.

“Secret” bling: Yes, bling! Romain Gauthier has his personal Logical One Secret paved with diamonds; Philippe Dufour has the “Number 201” Simplicity in a white gold diamond pavé case and buckle.

Bling is the thing: Dufour Simplicity Number 201 in white gold and diamonds (photo courtesy Michael H)

A distinct house style: If you had an opportunity to inspect a Dufour watch front and back, even in the absence of the brand marking it would be evident that it is a Dufour. I believe that the same is true for Gauthier: there is a clear and coherent style and a set of visual cues that distinguish his work and provide a foundation for future extensions.

Who else is in the running?

Even if we leave aside the fantastic watchmakers who are not independents, there are many wonderful craftspeople out there today. The intent is not to insult any of them here!

I’ve left out of the “contest” those who might more easily be considered Dufour’s contemporaries, but who quite likely don’t view themselves as the “next” anyone: folks like Kari Voutilainen, François-Paul Journe, and Vianney Halter.

Stephen Forsey and Robert Greubel have their own unique artistry and are, of course, already in active collaboration with Dufour. They certainly place timekeeping performance front and center, but their aesthetic to me is much less an extension of the Vallée de Joux style than is Gauthier’s.

Roger Smith will have to be content to be the “next George Daniels”; a very high accolade indeed, by the way!

The great movement designers like Jean-Marc Wiederrecht at Agenhor and rising star David Candaux as well as aesthetic design stars including Eric Giroud, deserve our respect, but they haven’t realized complete projects under their own brand names (not yet, anyway).

The Grönefeld brothers? Peter Speake-Marin? Konstantin Chaykin or Aaron Becsei? All excellent, but they don’t leave me thinking “Dufour” in the way that Gauthier does.

Ludovic Ballouard? Completely his own man, devoted to fun, and in some ways perhaps a highly gifted “descendant” of Alain Silberstein rather than of Dufour.

One dark horse: the young Geneva watchmaker Rexhep Rexhepi and his brand AkriviA. Rexhepi brings a strong background from his time at Patek Philippe; his designs, while quite contemporary, build on classic concepts; and his devotion to fine finishing is quite extraordinary. His work has already been nominated for one Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève award, and I expect that we will see a great deal to come from him in the coming years.

Parting thoughts

Perhaps the best expressions of my thoughts here are encapsulated in the inscription at the top of Gauthier’s website, just below his name: “The Evolution of Tradition.”

Philippe Dufour drew on tradition and made the design codes of the Vallée de Joux part of his own personal style. But he also extended into new areas and adopted “modern” techniques much earlier than many others. Gauthier started from that same tradition and incorporated the counsel of Dufour himself.

For me, at least, he is on the way to expressing the traditions of the Vallée de Joux in ways that are thoroughly relevant today and provide a strong foundation for the future.

For more information, please visit www.romaingauthier.com.

You may also enjoy:

Why Do Ultra-High-End Watches Cost So Much? Hand-Finishing At Romain Gauthier Sheds Some Light

Does Hand Finishing Matter? A Collector’s View Of Movement Decoration

Why We Are In A Golden Age For Appreciating Superlative Hand-Finishing In Wristwatches

Why I Bought It: Romain Gauthier Logical One

Romain Gauthier’s Ingredients Are The Best Basis For A True Value Recipe

Romain Gauthier’s First Automatic Watch Is A Stunner Called Insight Micro-Rotor, But We Expected Nothing Less From This Perfectionist Micro Engineer

Behind The Lens: The Philippe Dufour Simplicity

Behind The Lens: Philippe Dufour Duality

‘Time Piece’: If You Only Watch One Film On Independent Watchmaking, Watch This One Featuring Vianney Halter and Philippe Dufour

* This article was first published April 12, 2015 at Why Romain Gauthier Is The Logical Heir Apparent To Philippe Dufour.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!