If you’ve been lucky enough to travel to the “four corners” area of the southwestern United States (where U.S. states Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico “meet”), then you may have seen or even visited some of the cliff dwellings built by ancient Native Americans that were erroneously called Anasazi for thousands of years, and now go by the term Ancestral Puebloans.

The Ancestral Puebloans were nomads until about 300 AD when corn arrived in North America via trade with Mexican tribes. The advent of corn crops changed the Ancestral Puebloans’ lifestyle, and the previously nomadic clan settled down thanks to the seasonal rhythms attached to the harvest. That took place in the early Middle Ages; by about 1300 AD there were approximately 50,000 people living in the area.

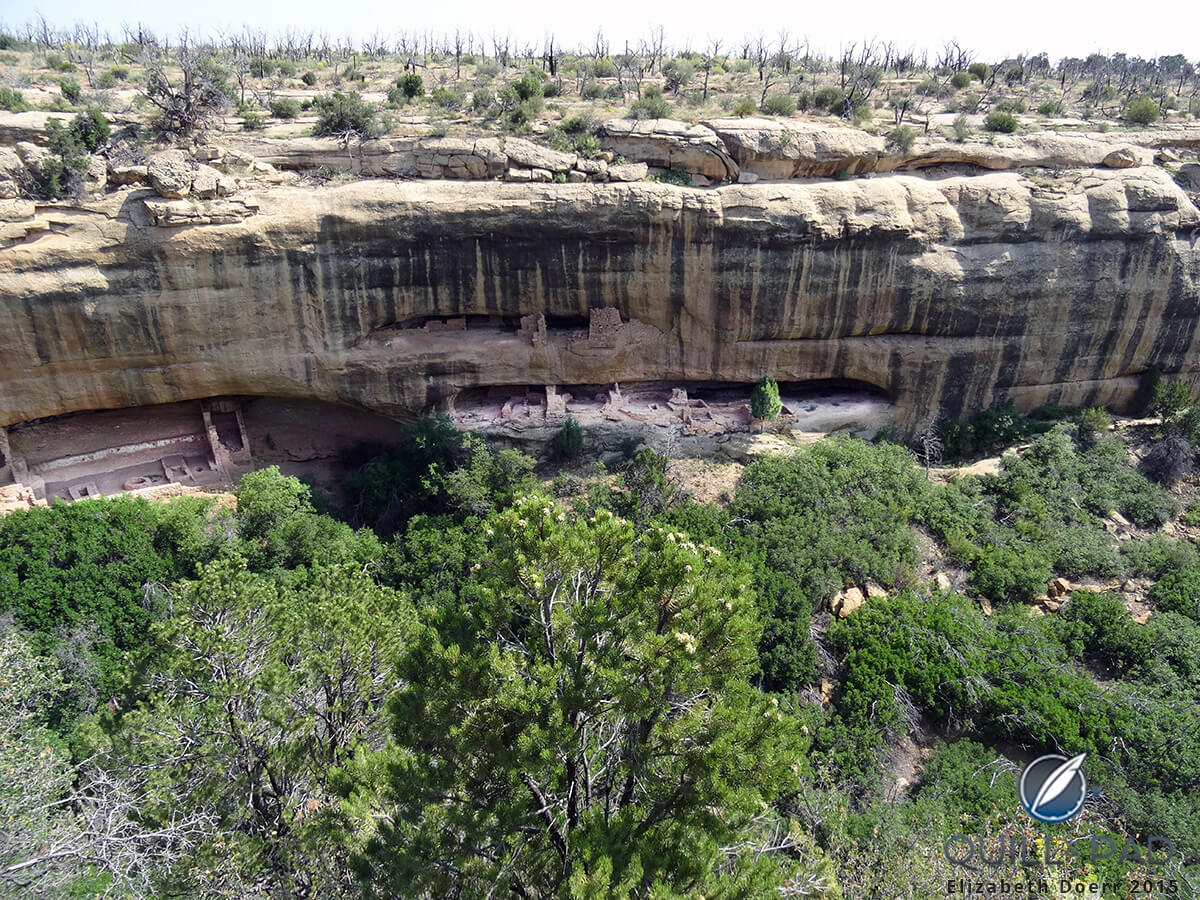

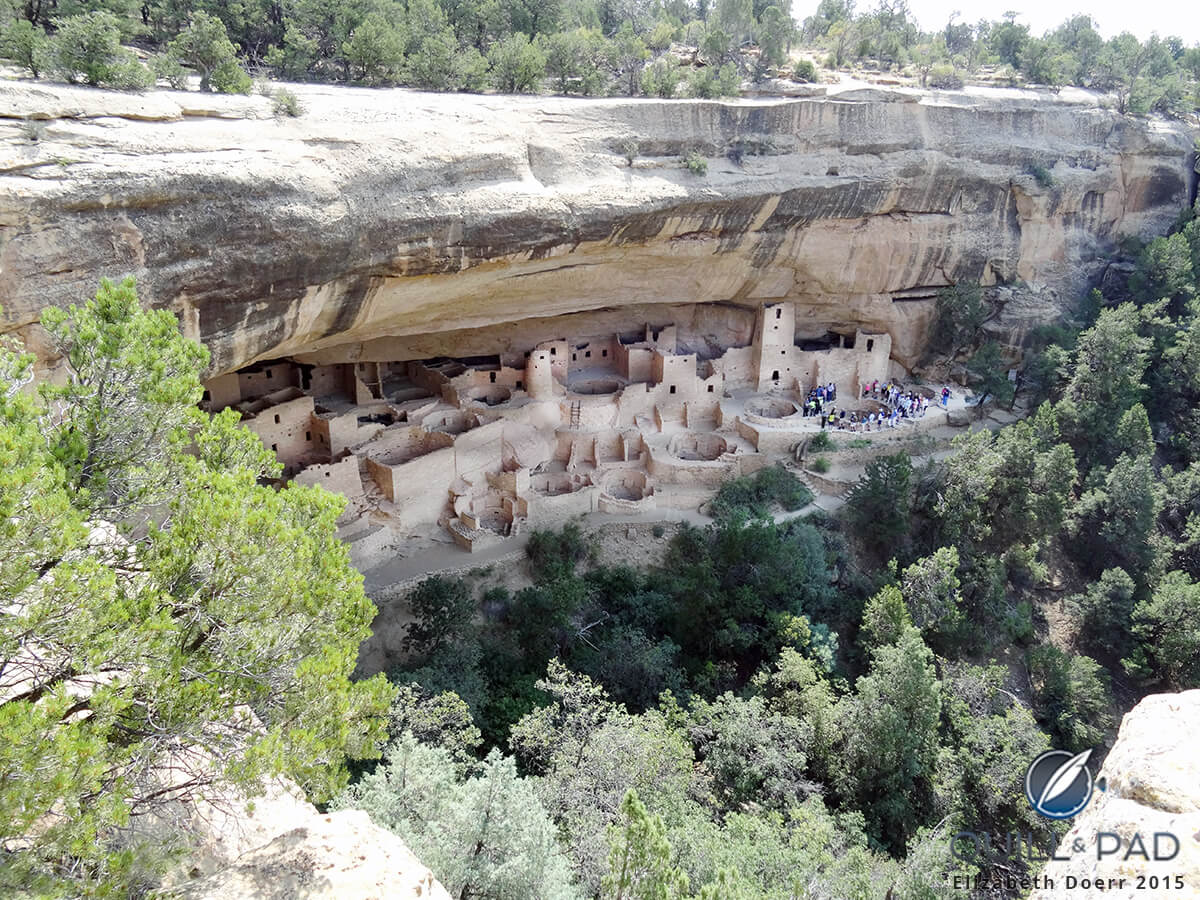

Mesa Verde National Park’s Cliff Palace, an almost fully intact cave-set village built by the ancient Ancestral Puebloans

Language nerd side note: the name Anasazi is an exonym from the Navajo language and translates to “ancient enemies” or “ancestors of our enemies.” The Navajo now occupying parts of the area as well as modern-day descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans prefer not to be called by that name.

“Puebloans” comes from the word pueblo – a small Native American community – in which the Ancestral Puebloans lived. Interestingly, the word “pueblo” itself comes from Spanish and means “village.”

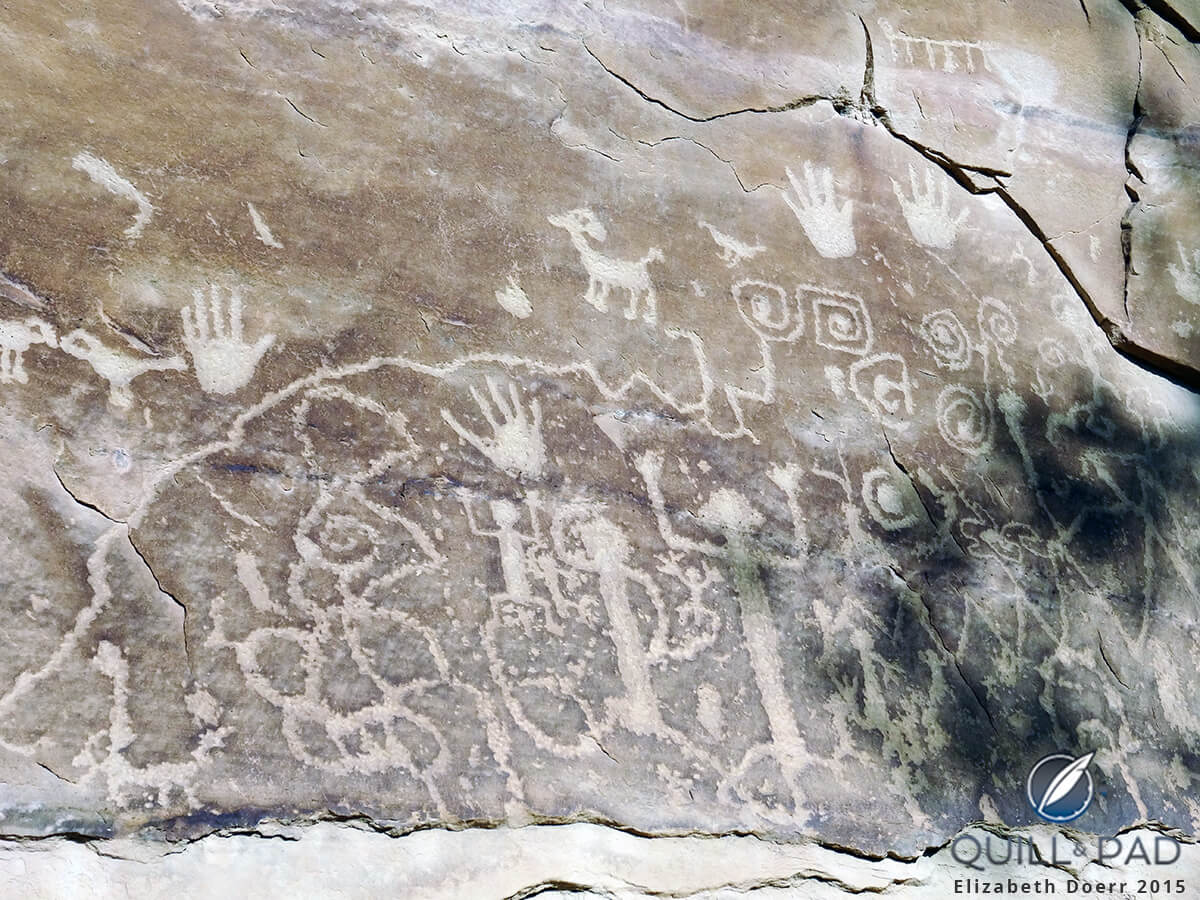

As the Ancestral Puebloans had no written language, everything that is known about them has either been handed down orally by descendants or surmised by combining the oral traditions with the few petroglyphs remaining in the cliff dwellings primarily found in Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde.

The cosmic order of the universe

Based on their agricultural lifestyle and the fact that they would periodically perform religious rituals, it seems that the tribe placed importance on divining the time – at least to within a few days. This is worth looking a bit closer into as the Ancestral Puebloans did not appear to have specific dates or calendars etched into stone like the Mayans, for example (see The World’s Biggest Man-Made Calendar: El Castillo At Chichén Itzá).

Thus, it is a little bit harder to tell if and how Ancestral Puebloans kept track of time. However, a few possibilities and examples have been discovered. At Chaco Canyon, for example, archaeologists found evidence of archaeoastronomy (the study of how past peoples understood phenomena in the sky) – in particular the Sun Dagger petroglyph at Fajada Butte.

Like other native tribes, the Ancestral Puebloans’ ritual dates were determined by high religious officials, who ensured that rituals and ceremonies took place at the correct times. The cosmic order of the universe was not only regulated in the Ancestral Puebloan world, it was taken as the law.

Mesa Verde National Park’s Cliff Palace, an almost fully intact cave village built by the ancient Ancestral Puebloans

The Ancestral Puebloans believed that both sacred time (for religious purposes or ceremonies) and secular time (“everyday,” non-religious time) was regulated by the sun, moon, and stars. And they believed it to be crucial that their events take place at the correct moment, with the sun, moon, and stars in the right positions. Such cycles were important to help regulate timing.

Time was indeed sacred, with the basic principles of astronomy used to determine the so-called “ritual calendar.”

Telling the seasonal time

One way they determined the time was simply to look at the height of the sun above the horizon and base estimates on that – much like early navigators did. This meant that the Ancestral Puebloans probably did not keep track of the exact hours and minutes.

In fact, during a trip to Mesa Verde, Ranger Dave Hursey – who guided my family and I through some of the cliff dwellings at Cliff Palace and Balcony House – pointed out that the long shadows cast by the mesas’ tall cliffs would have made sundials moot.

Ranger Dave Hursey explaining aspects of daily life at Mesa Verde National Park’s Cliff Palace, a village built by the ancient Ancestral Puebloans

Determining the time by looking at the sun over the horizon would usually have been performed by a so-called sun priest. This could be relatively accurate depending on what the tribe needed the time for; however, these observations were not especially precise when it came to specific times of the day. This did work fine for telling the season, though, the Ancestral Puebloans’ most important time cycle.

Knowing the season was vital because the tribe needed to know when to plant crops in order to avoid them drying out, thereby ensuring their success. Water was and remains extremely scarce in this part of the world, and the correct crop timing ensured the tribe’s survival. The area has very short harvest seasons due to its extreme altitude.

The Ancestral Puebloans kept track of “months” using calendar sticks.

More precise time

The Ancestral Puebloans fortunately had another way of telling the time for other circumstances when a more precise interpretation was necessary. One example would be to find the correct period of time for a celebration.

The cliff dwellings built within shallow caves generally faced south so as to maximize sunlight and thus warmth in the winter.

Mesa Verde’s Balcony House, however, faces eastward. This was so because some of its 40 rooms were used for astronomy purposes.

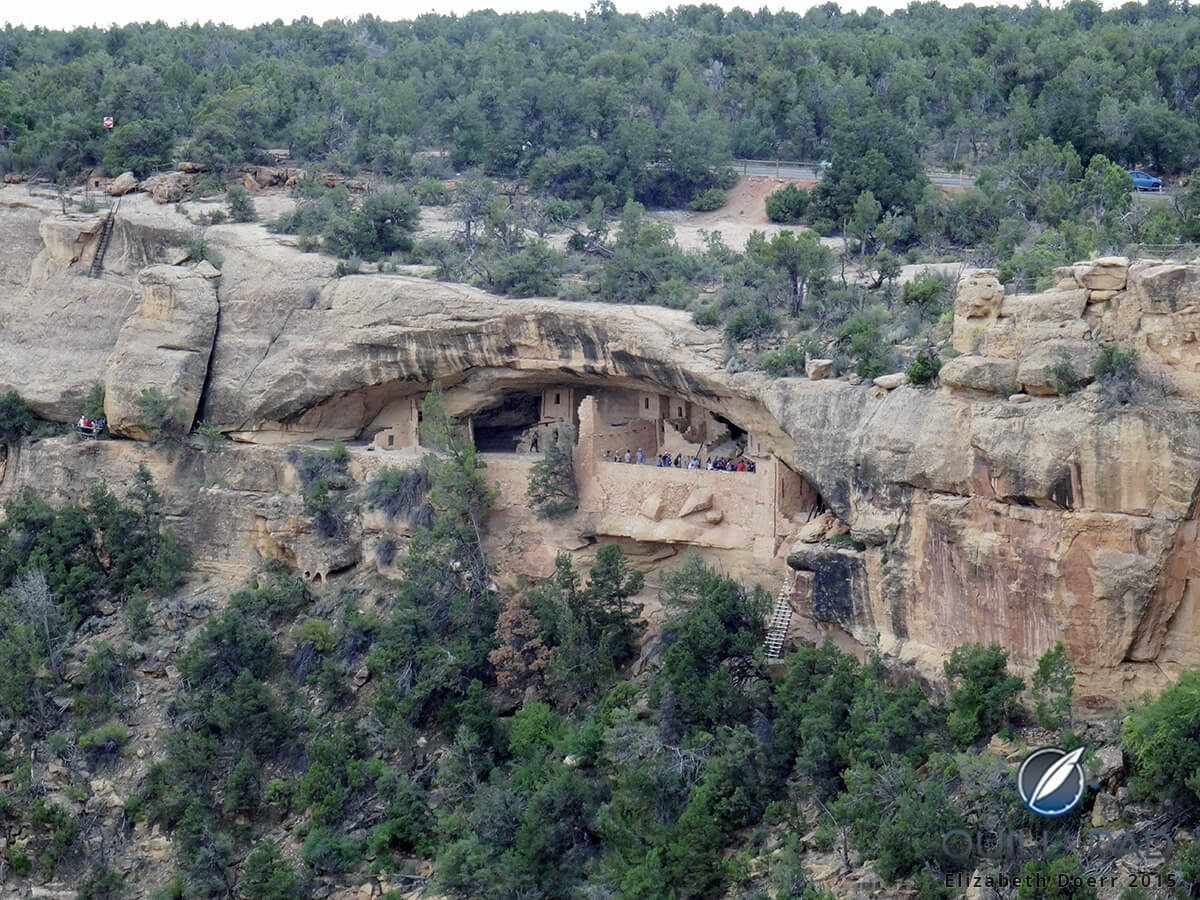

Balcony House in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado: this is one of the rare cliff dwellings that faces eastward instead of south for purposes of astronomy

The openings in eastward-facing walls of buildings allowed sunlight to shine through onto the opposite wall around the time of sunrise. On the opposite wall, markings or symbols correlating to the solar cycle indicated the season and even what time of the day it was.

The previously mentioned Sun Dagger petroglyph is a carved spiral solar calendar located at Chaco Canyon that is used with sunlight to relate the time. When the sun shines directly down the middle of the spiral, it is exactly 11:11.

Rooms 8 and 21 at Mesa Verde’s Balcony House also show such light play at the times of solstice and equinox, which was important for ascertaining harvest times and so on. However, no spiral “clock” markings have been found to date at Mesa Verde.

Room 21 of Balcony House in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado: the long wooden beam was used as a sort of gnomon for astronomically ascertaining the solstice and equinox

Looking at the photo above, we see a long wooden beam ranging out above Room 21 at Mesa Verde’s Balcony House. This long beam acts as a type of gnomon (the rod in a sundial that casts a shadow) during the solstice or equinox sun, which shone on a basin inside Room 21. The short beams also visible in the photo are used to support the upper story structures of the dwellings and have nothing to do with astronomy.

Judging by this strategy of timekeeping, we can conclude that the Ancestral Puebloans were fairly advanced in their timekeeping abilities – due, of course, to the fact that time was so important to their rituals (sanity) and basic everyday needs (food).

I’d like to thank Ranger Dave for his patient answers at Mesa Verde as well as Sabrina Doerr for her help in researching this topic.

For more information, please visit www.nps.gov/meve.

* This post was originally published on September 3, 2015 at How The Native American Ancestral Puebloans Kept Track Of Time.

You may also enjoy:

Car And Watch Spotting In Havana Starring A Cartier Santos Dumont And Beautiful Old-Timer Cars

Luxurious Wining, Dining, And Sleeping — Glamping, Anyone? — In Southeast Queensland, Australia

The How, What, When, Where And Why Of Seeing The Aurora Borealis, AKA Northern Lights

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!