Have you ever wondered how Titleist gets its logo on bumpy round golf balls?

Or maybe over your morning cup of coffee you have pondered how exactly the mug company was able to put “World’s Okayest Dad” in big black letters halfway around the mug.

Well this is your lucky day as I’m about to discuss the secret of one very specialized printing process that goes on in the world and how it has its roots in watchmaking. In fact, you still see the results of this process every time you look at your watch dial.

To be honest, the secret really isn’t a secret, but many people will not have had experience with this special form of printing that relies on very elastic rubber and specifically formulated inks to print on some truly irregular objects.

The method of printing I am talking about is the relatively modern and widely used process called pad printing. Though in the watch industry, it is often called by names that originate in French and German language: tampon printing (“tampon” is the French word for “pad” or “rubber”) and transfer printing.

Some of you may already be saying “Oh yeah!” while others are imagining a pad of paper being printed and wondering what that has to do with a novelty mug.

Pad printing, explained in simplest terms, is very much like a rubber stamp used in scrapbooking or to address envelopes by the hundreds. The idea starts with a rubber pad that picks up ink in order to transfer it onto an object.

That might sound pretty straightforward, but that is where the similarities start to run out.

Pad printing is really two parts science, one part skill, and a final part magic. But to really understand why I say this, let’s break it down into steps that will (hopefully) help you see why this seemingly mundane and ubiquitous process is actually pretty technically advanced.

The pad

The first component, and the most important one at that, is the pad. The pad is most often molded from silicone (not silicon, note the “e” on the end) rubber in one of a few basic shapes.

The three mains shapes are round, bar, and loaf, and all of them will vary based on the intended application. In the watch industry, it is generally the round shape that is used – which technicians call a balloon, a word that perfectly describes the shape of the silicone rubber instrument at work.

Different shapes and sizes of “balloon” silicone printing pads in a drawer at Richemont Group dial maker, Stern Créations

In other industries, different pad shapes will also be specially designed for even more odd, printed shapes.

The big secret for the pads lies in the durometer, or the measured level of hardness, usually based on the Shore scale. The durometer of the pads varies, again based on application, but it is common for the pad to be somewhere in the range of marshmallow or chewing gum soft, and can be firmer as the application requires.

The pad also does not have a shape molded into it like a stamp would; instead, it is smooth and picks up ink from the second main component, the cliché.

The cliché

”Cliché” is a fancy word for the image plate, which is where the master image that is printed onto the object, such as a dial, originates. The materials used for the cliché vary (again based on application and desired number of prints), but the most common material is steel etched with a very precise image.

The typical etching depth for a steel plate is 18 to 25 microns (about .018 – .025 mm). The ink is deposited in the etched portion and picked up by the pad for transfer onto the object to be printed upon.

About 50 percent of the ink in the etched sections is grabbed by the pad, somewhere around 12 microns for the 25-micron etch depth, and always in a consistent layer thickness due to ink viscosity (and some other subtle design choices for the etched surface).

That brings us to the third main component of the system: the special inks.

The ink

Pad printing inks derive from screen printing inks with a few notable modifications, the pigments being the big difference. Pigments in ink are a miniscule fragment of some colored material, many being synthetic but many also having organic origins.

The pigment grains are crushed to a precise grain size specific to the intended ink. For screen printing, the pigments can be somewhat coarse (tiny, but coarse in relation), but the pigments are rolled much finer for use in pad printing inks to help facilitate ink flow and uniformity in color.

The amount of pigment added to the inks is also much greater in pad printing inks in an attempt to improve opacity (meaning the lack of transparency) since the layer thickness for applied pad printing inks is much less than screen-printed inks. To achieve a proper flow of pad printing ink, it is usually thinned down to a ratio of 60 percent ink and 40 percent solvents that evaporate once applied.

Thanks to that 40 percent volume of evaporating solvent, the final layer thickness of a pad printed ink can be around 8 microns (.008 mm). For this reason, the pigments must be much smaller and in a much higher concentration so that light does not pass through and create a see-through print.

Many additives are also combined with the inks to precisely control the flow rate, how well it adheres to specific materials, and sometimes to even create conductive inks.

The process

By putting all of those components together (plus a mechanism for controlling placement), you create a unique printing process for a variety of materials of infinitely variable shapes. Those materials are referred to as the substrate, which simply means the surface you are printing on.

But how exactly does it work?

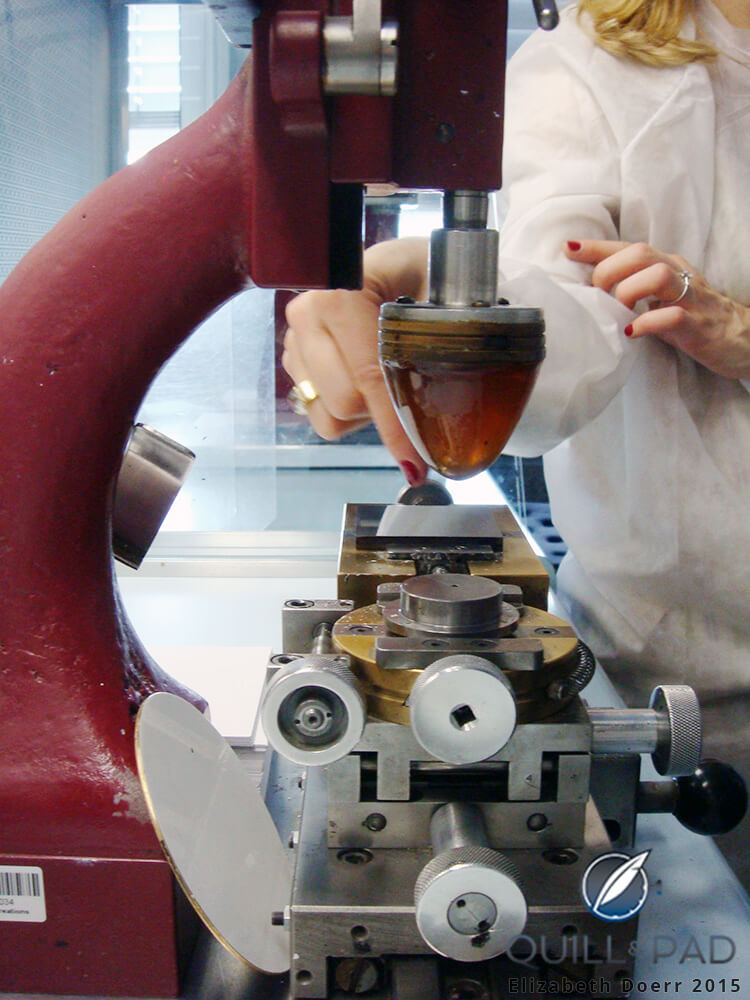

First, the cliché is primed with ink. In automated processes, this is done in a few different ways but the goal is ultimately the same. Let it be noted that this is generally not an automated process in fine watches; the dial maker generally hand-prints every dial.

An excess amount of ink is applied over the etched surface, filling all of the recesses. Then a squeegee or blade is drawn across the surface, removing all of the excess ink.

Next, the pad is pressed down onto the cliché, squishing out over the entire etched portion. Due to evaporation of the solvents the ink has become tacky, which allows it to transfer to the silicone pad.

The inked image can look very distorted on the pad once it is pulled off of the cliché due to the shape of the pad.

In many machines at this point, the cliché and the substrate change places, usually via a sliding table that moves back and forth. The portion where the substrate lies is typically on its own multi-axis sliding table. This table can have up to six micrometers attached for precision adjustment to ensure exact alignment of the print on the substrate.

At a dial maker, the cliché and the substrate generally do not change positions.

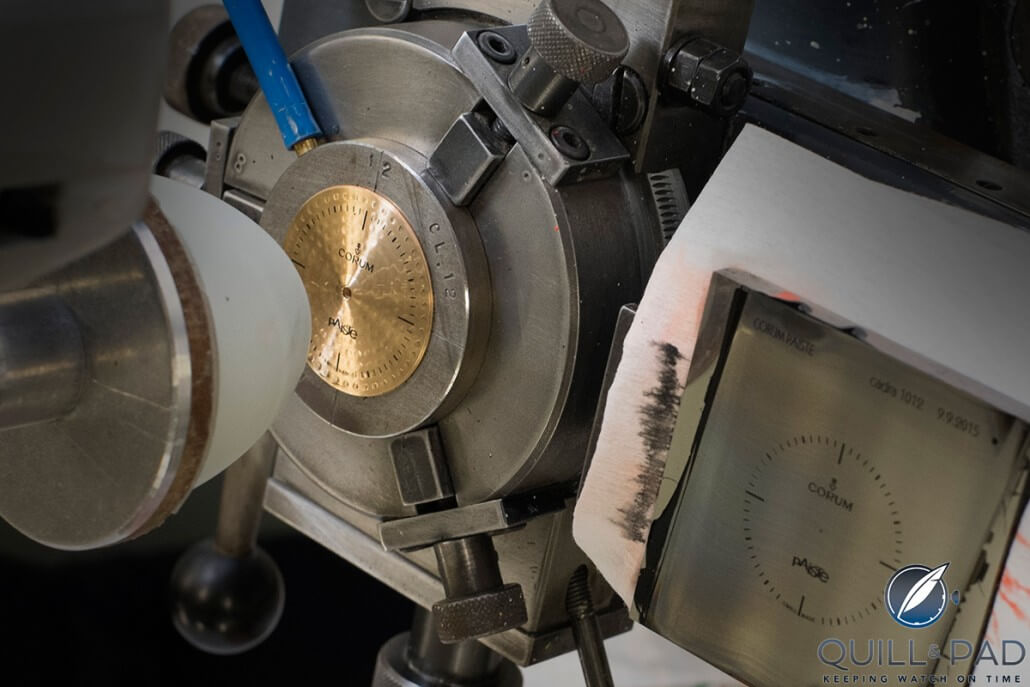

On many objects, like a mug, the exact alignment is not very critical, but on something as small and precise as a watch dial, the ability to dial in (no pun intended) the alignment with absolute precision is crucial.

When the substrate is in position and locked, the pad lowers onto the object and thanks to the very low and squishy durometer of the silicone, it deforms around any irregularities. In some instances, it can look like a blob enveloping a small object. But in fact it is precisely depositing the ink onto the surface.

Depending on the object and the requirements for the inked image, different amounts of pressure can be applied, and firmer silicones can be used. Also, the image can be repeatedly inked for a much more pronounced image height that provides a sense of depth. Some watch dials may be inked multiple times depending on ink, dial material, and desired appearance.

Dial of a Senator Chronometer (left) and a PanoMaticLunar (right) being pad-printed at Glashütte Original’s Pforzheim dial maker

Why it matters to watchmaking

The reason this process is so important to the watch industry is that it very possibly originated from within the industry itself! There is no known definitive creator of pad printing, and the process is somewhat old.

Only in the middle part of the twentieth century had rubber technology advanced enough to make the process extremely capable and therefore valuable to a multitude of industries.

The origins of the process are considered to be in the clock and watchmakers’ need for more efficient ways to paint dials using another means than by hand. Watch dials became smaller as wristwatches became more common, and the need grew for automated processes – particularly in the U.S.A., where the manufacturing of timepieces really underwent its industrial revolution in the pre-war era.

In the second half of the twentieth century and thanks to advances in material science of the likes of 3M, Dupont, Corning, and other industrial giants, materials were finally catching up to the desires of engineers. Watch dials were some of the earliest widespread uses of this growing process.

This process is now major in the modern printing industry, and almost every electronic gadget, thingamabob, and doohickey in your house could very well have pad-printed graphics applied.

Look at buttons with graphics on almost anything and they are probably pad printed. Logos and graphics on hard packages that aren’t stickers (and even some that are) are very likely pad printed.

At this moment, without even turning my head I can see a dozen different objects with pad printing around my desk. And, of course, my watch dial is pad-printed as well.

The process is simple in the explanation, but very complicated to get to work just right. It takes a fair bit of knowledge in scientific principles of adhesion, viscosity, material flexibility, light transfer, and fluid mechanics.

Add to that knowledge a fair amount of skill and perfectionism (especially on manual machines), the proper setup, preparation, and accomplishing the actual process and pad printing becomes something much more incredible than a rubber stamp.

The bit of magic that is involved comes with the pad design and the silicone’s miraculous ability to perfectly bend and warp around irregular objects, applying ink in a way that is perfectly square and aligned on something that could never be described as such.

So take a look around you sometime, or take a gander at your watch dial, and see how pad printing is represented in the world you inhabit. You really might just add another level of appreciation for that beautiful dial on your vintage Submariner that has perfectly crisp numerals and logos applied thanks to some magic rubber and some slippery ink.

* This article was first published on December 20, 2015 at Focus On Technology: Pad Printing.

You may also enjoy:

Here’s Why: Stainless Steel Is The Most Precious Metal

Detailed Primer On Gemstones And Their Appreciation: An Introduction To The Finer Things

The Truth About Magnetism And Watches

Deeper, Further, Faster: Why Do Some Dive Watches Have Helium Escape Valves?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!