You have just spent the entire weekend having an epic movie marathon of some of the most distinctive films that portray the Gothic, surrealist, horror-filled imagination of visionary artists, directors, and animators. It’s the middle of the night, and after binge watching works from the likes of Guillermo Del Toro, Tim Burton and others, you slowly drift off into a fever-filled dream full of sights and sounds that make your heart race.

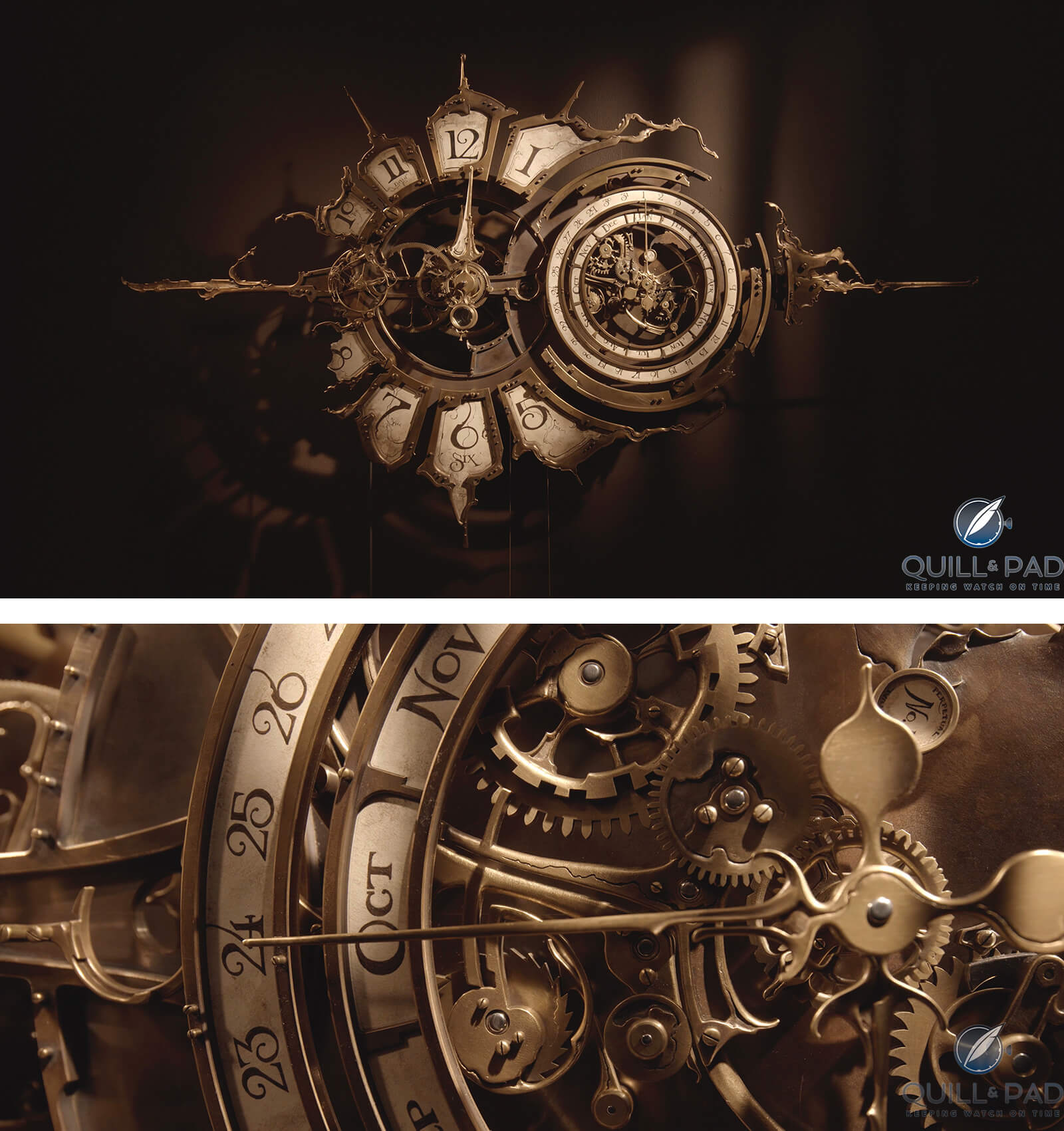

Bits of all that you watched creep in: the castle from The Dark Crystal, the angel of death from Hellboy, the graveyard in A Nightmare Before Christmas, the faun and the dagger of Pan’s Labyrinth, all melting together into a feeling of fear and awe. Then darker images fade into focus: the clock head from Dark City or the nightmarish horrors of Event Horizon, all the while a pounding rhythm is beating in your ears. A random memory of your trip to MOMA materializes and you see the melting clocks of Salvador Dalí, and the beating turns to ticking as it all swirls through your mind.

You see a flash, a single image, and then awake, bolting upright in startled surprise. You’ve had a vision. Shaking, you reach for your notebook and open to a blank page, taking a pencil from the nightstand and, putting graphite to paper, begin to sketch. Frantically for minutes or hours, you won’t remember, you draw an image of Gothic surrealism interlacing nature with mechanics and time. Indiscernible time passes and you fall onto your pillow exhausted, immediately sound asleep while the notebook slips to the floor.

The sun is shining and you awake, only vaguely aware of the previous night’s insanity. As you swing your feet over the edge of the bed you see the notebook on the ground, open and face down. Picking up the leather volume you are still blind to what you are about to face. Flipping it over an image stuns you, causing it all to come flooding back: the visions of twisting shapes and crunching gears, of darkness and metal that flows like silk, driven by its own devices. It’s a machine of time, warped by nature and the relentless decay of time itself.

Can you imagine?

Eric Freitas at work

I can because that is basically what went through my head when I first pondered the incredible masterpieces of surrealist Gothic sculptor and self-taught clock maker Eric Freitas. If you are unaware of his work, the best way I can describe the aesthetic of his creations is a combination of the styles of Guillermo Del Toro, Tim Burton, Salvador Dalí, and the entire production design of Jim Henson’s The Dark Crystal if they were combined into an intense mechanical wall clock.

In the beginning

Eric Freitas didn’t start making clocks due to some love of horror, but as a fascination with clockmaking and a background in illustration and design. He graduated from the College for Creative Studies in Detroit in 1999 as an illustrator, though it wasn’t until 2003 that he started on his first clock. In the intervening time, Freitas worked as a professional illustrator and realized the highly constrained work was not where his passion lay.

He yearned for creative freedom and wanted to find his passion for design and aesthetic that was lacking in the corporate design environment.

Freitas didn’t necessarily set out to create something specific; in fact, the style of his clocks comes not from a desire to mimic external inspirations or pay homage to any artist but instead out of the act of artistic play.

Eric Freitas

Freitas’ aesthetic was born out of free sketching where he put pencil to paper and let random lines and curves develop into shapes, slowly teasing out a direction as he began to see something he liked within the undirected sketches. He latched onto the shapes that felt right and took them further; think advanced doodling for the trained illustrator.

Even the idea to make clocks came first from sketching for enjoyment after college. After a while, he noticed that clocks and time began to feature more and more within the sketches and an idea took hold. As he was only familiar with using a jeweler’s saw, mostly thanks to a teacher in high school that taught Freitas how to make pendants out of sheet metal, he started making quartz clocks using hand-cut designs based entirely on his newfound style.

Not once in his life has Freitas made what you would consider a normal or traditional clock; from the beginning his style was pulled straight from his illustrations depicting clocks one might describe as being tattered and worn by time and nature.

Freitas’s earliest clock did not feature extensive three-dimensional sculpting and engraving; this came later to more closely achieve his artistic vision. Wearing out multiple Dremels before acquiring a Foredom rotary tool (the industry standard in watchmaking, clockmaking, jewelry making, engraving, wood carving, etc.), the complexity and precision of his metal sculpting grew with each new clock.

After creating around a dozen quartz clocks and finding the book How to Make a Skeleton Wall Clock by W.R. Smith, Freitas ventured into making fully mechanical clocks. Thanks to his father, an automotive engineer, Freitas was gifted with a metalworking lathe and a manual milling machine giving him most of what he would need to create whatever he could dream up.

Freitas’s first mechanical clock, developed using the step-by-step process in the Smith’s book, was entirely non-traditional and resembled the example from the book in function only. Again, at no point did Freitas set out to make traditional clocks or even start simple and work up from there.

Eric Freitas Seven Six Five

Over the years he has toned down some ideas as he has pushed up against what is possible when making these clocks. He discovered the areas that cannot be modified due to engineering and clockmaking principles, but everything else has always been fair game.

Into the swing of things

Every clock that Freitas has made is an exploration in shape, texture, and aesthetic. When he tackles the metal sculpting, for instance, he works from his preliminary sketches but attacks the metal with burrs and files, letting the flow of engraving and the metal itself direct the final product. The overall vibe follows the outline sketches, but the detail of the sculpting will develop organically from his two hands.

Eric Freitas Quinquagenarius clock

That is the essence of his aesthetic in the first place, an organic style that grows like a piece of nature, twisting and flowing without rigid constraints, acting as if alive. Freitas describes his style succinctly as, “the precision of centuries-old mechanics mixing with the strange chaos of nature.”

This chaos also combines with the repetitive nature of fractals and number patterns like the Fibonacci sequence to drive proportions, another thematic element present in his designs.

Evident in all of Freitas’s clocks, be they quartz or mechanical, he wants the designs to grow organically in the hopes that they feel as natural as possible. Freitas feels his “fingerprint” has developed greatly over the past 16 years and more than 50 clocks, to a point where each piece is so intertwined with the time and place he created it that each clock is truly a one-of-a-kind object that could never occur again.

With that has also come the internal understanding over the last few years that he is, in fact, a clockmaker and not just an illustrator that happens to make clocks. It has infused the entirety of his being, and that can be seen when you look upon his work.

Mechanical masterpieces of nature

In 2014, after a decade of making clocks, each one a unique experience, Freitas was approached to do something new (newer than a completely one-off clock): a free-standing, multifaced, large-format clock installation. This would come to be known as the Jungers Commission after the patron who commissioned the project.

Spanning two years and comprising more than 5,000 hand-machined parts, the 7.5-foot-tall clock took shape and pushed Freitas in every way. The scale was unlike anything he had ever attempted before – the complexity as well – and with the sheer number of sculpted parts, it’s no surprise that the build took at least 2,421 hours to complete.

Eric Freitas Jungers Commission clock

When it was all finished and installed as the centerpiece of an impressive wine cellar (which was designed around the clock), it boasted six different dials including two time zones, a moon phase, and a day indication, all viewable from any angle.

This shows off the intense work that Freitas has done with each custom-made component and the extensive sculpting and shaping. The chain for the driving weight consists of 420 individual components, with each link in the chain a unique handmade design. Aside from the screws and a few specific components, the entirety of the Jungers Commission clock is an assembly of thousands of uniquely sculpted parts that highlight both the client’s and Freitas’s aesthetic passion.

The Jungers Commission also led to Freitas adding complications and additional dials into his other works as only one other mechanical clock before this had anything beyond a simple hour and minute display.

After some well-deserved time off after the massive two-year build of the Jungers Commission, Freitas created a string of pieces that clearly demonstrate he is in peak clockmaking condition.

Eric Freitas Twisted Twelve clock

The Redux V and the Twisted Twelve are two incredible examples of his dramatic style and clever use of seemingly superfluous details to inform how one experiences his clocks. Whether it be a clock that has almost been entirely consumed by and returned to nature (Twisted Twelve) or an artifact of an ancient, secretive civilization (Redux V), the aesthetic takes center stage.

Eric Freitas Paper Moon

This was followed up by Paper Moon, a moon phase clock that also brought back some painting skills from Freitas’s illustration days. Around the same time he was commissioned to create a piece for a fiftieth birthday inspired by one of his earlier designs, which resulted in one of the most dramatic drive chains I have ever seen. Even with the extra dial displaying seconds, the drive chain is a standout assembly and shows the incredible amount of detail work that Freitas puts into these creations.

Eric Freitas TH3

Another clock Freitas finished in 2019, the TH3, is an awesome example of how he likes to play with orientation and layout within the clock movement itself. Not that any of his clocks follow standard shape or layout rules, the TH3 is an extra-long landscape-oriented piece that distributes the movement so one can see the entirety of how it works.

The spread also turns what a clock usually is on its side as the pendulum swings off the far-left end while the driving weights hang slightly off center to the right. The visual creates some mental dissonance as it just seems counterintuitive that a clock could work like that, but this dissonance is part of the organized chaos that Freitas likes to create.

High complication

And if that was where Eric Freitas had retired, one would have no qualms saying he was a great clockmaker and designer. But Freitas is young and not done yet. In 2019, after about a year and a half of incredibly detailed work, he released his first high-complication clock, a perpetual calendar appropriately called Perpetual No. 1.

It began with an idea and then a call for help. Reaching out to watchmaker extraordinaire Vianney Halter (good company to be in), Freitas discussed his idea for a perpetual calendar clock and asked if Halter may have some reference material he could use during the planning and construction of his idea.

Vianney came through and sent Freitas a bunch of books and resources on perpetual calendar mechanisms. But Vianney being Vianney, the resources were all in French.

Clockmaker Nerd Side Note: Eric Freitas does not speak French. Nor does he read French.

Freitas was incredibly grateful for the assistance, but now he had to spend hours (and days) on Google Translate to slowly extract information from the pages so he could continue to design and construct his first high-complication clock. One of the books did happen to have an English version, so he purchased that. But the rest was carefully translated as much as was needed, and the clock began to take shape.

Eric Freitas Perpetual No. 1

A perpetual calendar is a difficult mechanism to create, and in the best of times a talented clock- or watchmaker hopes for it to simply work. But Freitas always bends the mechanics to fit his style. This led to changes and additions to the design and functionality to fit within his vision and saw the addition of some features specifically for visual effect.

In the perpetual calendar gear train, Freitas added a set of drag fans to slow the date change (which happens at the stroke of midnight) so the function would be smooth and highly mechanical.

This also demonstrates both the mechanics and the seeming relation to nature, which tends to operate as smoothly as it can get away with. The result is a beautiful mechanism and a fantastic animation as the date changes. And since it is a perpetual calendar, the changeover on February 28 of a leap year is immensely satisfying.

Even though every clock that Freitas creates is a one-off never to be replicated, I could imagine this becoming a highly sought-after model, or at least lead to a few commission requests for perpetual calendars using a similar mechanism function.

As clocks go, this is a terrific creation to tickle the fancy of those who dig unique (and darker) aesthetics as well as complicated mechanics. After a decade and a half of clockmaking, the Perpetual No. 1 is set to become a signpost for Freitas and his creations.

Building a legacy early in a career

Following his very first mechanical clock and the bombastic Jungers Commission, his first high-complication clock does not abandon his signature style in favor of simplicity.

The Perpetual No. 1 was such a labor of love that Freitas actually stopped keeping track of the hours invested, making this one of the only clocks for which he does not know this exact information. But he does know that he’s just getting started.

Freitas says that he has so many sketches and ideas that he could never possibly hope to build them all in a lifetime, especially at the current rate of two to four clocks per year. So for now he is just going to keep focusing on the ideas that inspire him the most and work on as many commissions as possible to keep the creative juices flowing.

Plans are supposedly already underway for Perpetual No. 2, and ideas are being tossed around for another project of a similar scale to the Jungers Commission.

Clearly these won’t be for everyone, but for those attracted to Freitas’s work, you are bound to be enamored the more you dive in. The details he injects into what could be a very simple object are astounding, and the combination of mechanics and “the strange chaos of nature,” as he says, combine to make a work of art bound to be the centerpiece of a collection. There really isn’t a way it could be any less.

For more information, please visit www.ericfreitas.com.

Quick Facts Eric Freitas TH3

Body: 24” x 10” x 6” in brass, steel, and paper

Movement: 8-day weight-driven pendulum clock with dead-beat seconds and maintaining-power assemblyFunctions: hours, minutes, seconds

Price: $18,000

Mechanical clocks start at $16,000; quartz begin at $2,000; open for commission.

You may also enjoy:

Discovering The Secret Of Life With David Walter: Watches, Clocks, And DeeDee’s Tourbillon

De Fossard Solar Time Clock: Appreciating An Extreme Achievement Without A Loupe

Artist/Engineer/Clockmaker Florian Schlumpf’s Deconstructed Time

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Virus will pass I am buying ONE

You will only regret that you didn’t pull the trigger sooner. The work must be seen to be believed and, if that is difficult, know that it is much cooler in the metal than in pictures. Truly extraordinary craft and genius.

As word continues to spread about Eric’s genius, I hope that he will be able to carve out some time for me when the time is right. A note to those out there considering a commission – Eric was an absolute dream to work with and that, when dealing with “creatives,” is much more the exception than the rule. Two warnings: you will need extra room in your friend pool for Eric after a project and if you ask him if he can do X, he will say “yes” (and he absolutely can) and you will be off to the races (so be ready!).

Thank you so much for weighing in!