Here’s Why The Crown Is The Unsung Hero Of Watchmaking (And Why Rolex Wears The Crown) – Reprise

As a watch enthusiast, you may agree that Rolex has the most important “crown” in the watch industry. And after decades’ worth of watches like the Submariner and other iconic models, it would be hard to argue that Rolex isn’t deserving of its signature royal headgear.

A Rolex crown

But that crown owes its existence to one of the most important yet under appreciated parts of a watch: the aptly named crown. Yes, the humble crown has played an extensive role in helping Rolex – and the rest of the watch industry – get to where it is today.

The Rolex Oyster case

Rolex made history with the Oyster case, a three-pronged feat of engineering that included the first screw-down crown for water resistance. You might say that the Oyster case, and by extension the waterproof crown, is one of the main reasons Rolex is what it is: the brand understood that a great watch needed to be functional and secure, and the crown plays a large part in that since you use it every day (at least you did in the 1920s).

The crown is the second (behind the strap/buckle) most interacted with component on the watch (see Here’s Why A Watch Strap Is More Than Just An Accessory).

The crown is how we wind and set a watch and, on a manual-wind timepiece, it is used every single day (in most cases). It is the only part of the movement that you can touch, and it is crucial to the life and longevity of a watch for a variety of reasons.

The impressive crown of the Urwerk UR-105 CT Black

But it is also one of the most widely missed opportunities for design and engineering, at least as most widely consumed watches go. So today I want to provide a bit of background and discuss the deceptively complicated watch crown, and in doing so attempt to show that the crown of your watch is an unsung hero in the watch world.

The crown was no accident

The watch crown does not have a humble beginning, but a royal one (sort of). Just hear me out.

The mechanism of the keyless works in conjunction with a crown appeared around the middle of the nineteenth century, meaning that there had been at least five centuries of post-dark age monarchy rule by this point. Even though the French revolution had taken place 50 years before the invention of the keyless works, there was still a strong royal presence throughout Europe.

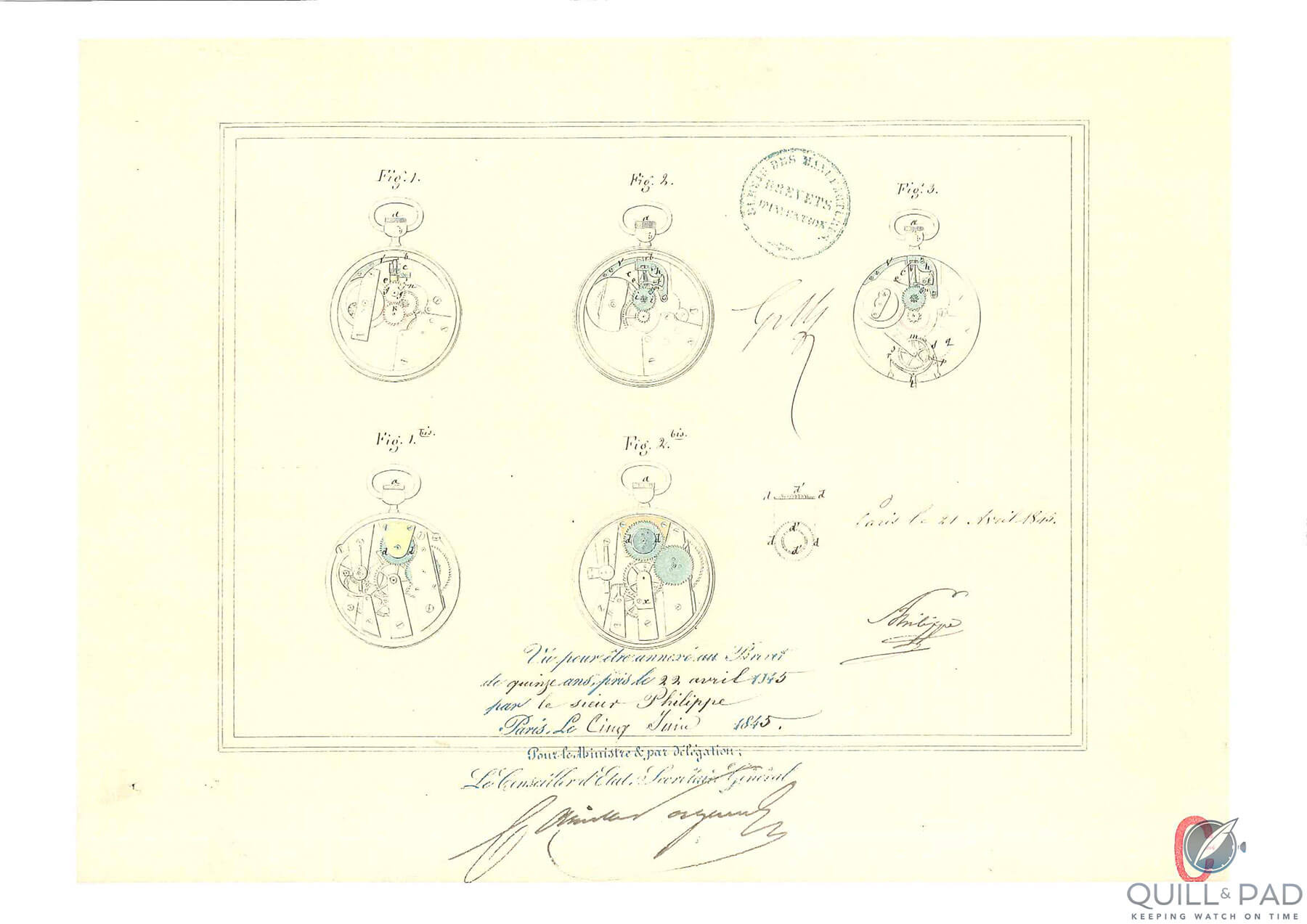

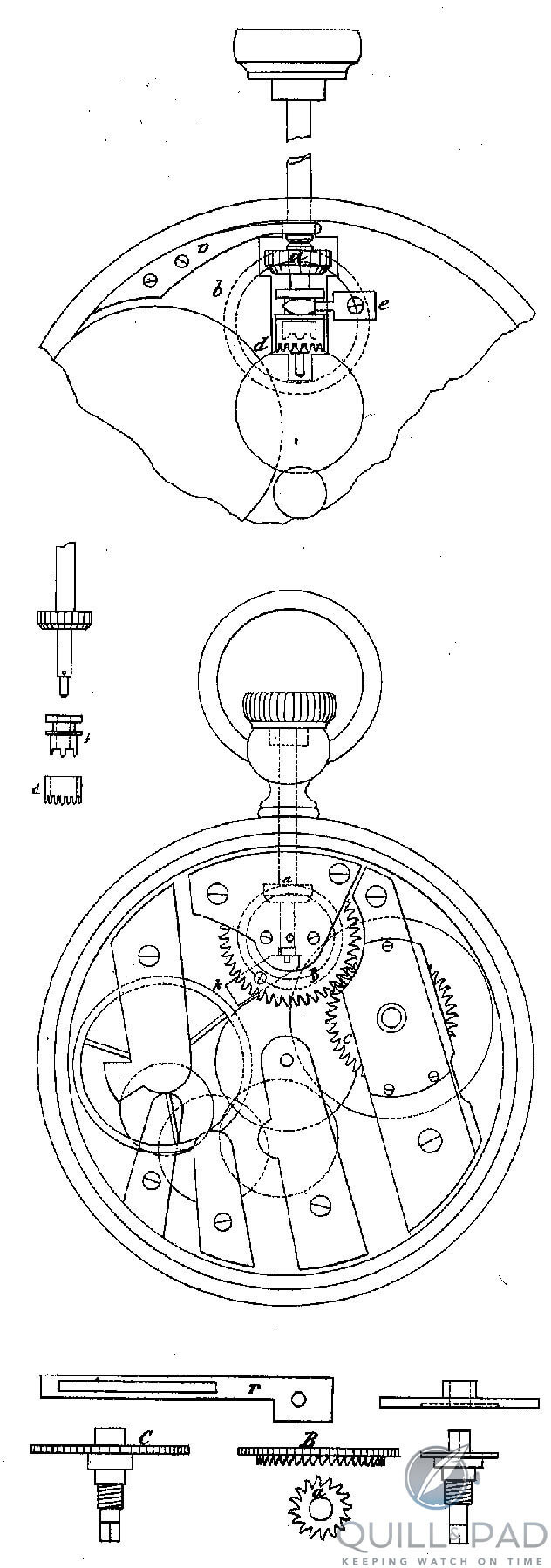

A patent awarded to Jean Adrien Philippe, co-founder of Patek Philippe

So in 1842 when French watchmaker Jean Adrien Philippe (co-founder of Patek Philippe) invented a system that used a permanently attached knob to interact with the movement instead of the ubiquitous winding key, the resulting shape of said knob must have resembled the now well-known royal headgear seen on kings and queens for centuries.

1821 patent for Jean Adrien Philippe’s keyless winding system

On most pocket watches at the time, the winding “knob” was at 12 o’clock: at the “head” of the watch. The newly fashioned knob became the “crown,” and many pocket watch crowns do share a striking resemblance to the crowns of the northern European royalty.

Crown of an A. Lange & Söhne pocket watch (left) and crown of Queen Elizabeth of Romania

A side-by-side comparison of a 1925 A. Lange & Söhne pocket watch and the crown of Queen Elizabeth of Romania from 1881 illustrate my point.

The crown has become a mainstay on nearly every watch since and has played an essential role in both engineering and design.

The crown, as I mentioned before, is the only part of the movement you can touch. As such, it can be very delicate, but must also be robust and easy to use. It is also required to be multi-functional and one of the main protections for the vulnerable movement inside.

Functions evolve

Early on, the crown was mainly a permanent replacement for a winding and setting key, which might require there to be at least two open, unprotected holes in the case or an entire case back that could open, also allowing dust and debris into the movement. The need for a more secure case was obvious, and a permanent winding and setting knob would reduce the chance of something getting into the movement.

E. Howard and Co pocket watch with square pegs for winding and setting the time with a key (photo courtesy Derek Weinberg)

Rubber gaskets and screwed case backs had not yet been invented, and the tolerances of the winding stems and case tubes would leave much to be desired compared to our modern watches. They were nearly dustproof, but only on the well-made pieces with the tightest tolerances.

Practices of using oils, waxes, or adhesives to “seal” cases shut couldn’t really be applied to winding stems and so there was always a way things could enter the case. Leather, felt, and cork gaskets were also tried, though these proved only marginally better than precisely made components; their natural composition making them prone to degradation fairly quickly.

The solutions also turned to caps that would screw over the crown, which eventually led to the incorporation of threads into the crown. The first designs appeared in 1881, and the screw-down crown was officially born.

The early designs weren’t widely used; one of the patented designs may have never even been produced. But all of that changed in 1926 when Hans Wildorf purchased a patent registered the previous year for a spring-loaded, gasketed, screw-down crown.

It was developed into a later patent with a clutch and relocated gasket, among some other details, which proved much better. From there on the world of watches fundamentally changed.

Eventually, rubber gaskets made their way onto the scene and dramatically increased the options and varieties of ways to seal the crown thanks to its unique properties. While vulcanized rubber was invented in the mid-1840s, the rubber o-ring wasn’t invented until 1937, so any rubber gaskets were considered more of an outlier than a standard feature until the wider commercialization of rubber o-rings and gaskets.

Functional design

Since then, numerous designs and ideas have been used to create passive and active sealing for the crown. When combined with other case and crystal changes, the crown is now the only place that dust or moisture can get in unless something has been assembled incorrectly, and then only during use.

A Rolex Twinlock crown

Designs range from a single to multiple o-rings, varying shoulder lengths on the crown, stem, or case tube, internal or external threads on the crown or case tube, or a combination of multiple solutions.

There are still watches featuring screwed-on caps that go over the crown, and some watches feature mechanisms that you must activate to be able to pull the crown to a setting position; Panerai and Graham produce two great examples of this.

Ballon Bleu de Cartier Moon Phase

Some pieces, like the Cartier Ballon Bleu, simply feature a basic waterproof crown with a protective arch, making accidental pulling of the crown less likely. But outside of that, the majority of crowns have functioned in the same way for the last 70 years or so.

And that is because the design is extremely functional and serves its purpose with remarkable consistency. The wristwatch is effectively completely waterproof, in some cases up to 3,900 m/12,800 feet (Rolex again).

No longer do people have to worry about where they wear their watches because in many cases they are built to handle just about anything.

Graham Chronofighter Vintage Nose Art Kelly: note the extensive crown gear

While you may see the crown as just a simple knob to set or wind your watch, it is just as precise and crucial to the proper functioning of your watch as many other parts. The difficulty of producing a crown is why many independents and major brands outsource crown production (seriously, the tiny spring-loaded clutch needs to fit within two millimeters in diameter and be strong enough for you to wind vigorously). It truly is a unique feat of micro engineering.

But that is also the problem: creativity stops when people think a goal has been reached. Sometimes reaching a goal allows people to relax and move on, which eventually leads to stagnation and boredom.

This is why some of the most incredible watches ever made from the likes of Greubel Forsey, Patek Philippe, De Bethune, and F.P. Journe don’t do anything different with the crown than watches from Casio, Swatch, or Michael Kors. The shapes might be a bit different, and in the case of F.P. Journe, extremely tactile and beautifully restrained, but they still function in precisely the same way.

This leads me to wonder whether brands understand how incredible the crown is and why it deserves to be treated with more respect and intentionality.

Trying something new

Like most things related to watchmaking, tradition trumps. And so making watch crowns like they have been made for over 150 years makes sense to many brands.

But some just don’t want to follow the status quo, but explore the way we connect and interact with our watches. Brands like Romain Gauthier, Ulysse Nardin, and even the wildly interesting Ressence look at the crown and realize there are some options there, ways of thinking about interaction that others might have missed (see Ressence Type 2 e-Crown Concept: The Right Combination At The Right Time).

The Romain Gauthier HMS Ten features a flat crown on the back

Romain Gauthier moved the crown to the rear of the case on the Prestige HM and HMS so that the mechanism and its interaction could shift perspectives, altering what we think of when winding and setting a watch (see Romain Gauthier Celebrates Ten-Year Anniversary With HMS Ten). This also simplified a mechanism that is prone to breaking or wear since it doesn’t have to translate rotational motion 90 degrees, simultaneously eliminating beveled gears.

Romain Gauthier’s Logical One features a pusher on the case band to wind and a small crown at 2 o’clock to set the time

Ulysse Nardin used the Freak as an experimentation platform and developed ways to use the bezel to wind and set the watch, eliminating the delicate winding stem and traditional crown and creating a more distributed seal between the outside and inside of the case.

Ulysse Nardin Freak Lab

Ressence took everything one step further (twice) and tried to completely reinvent the way a person interacts with a timepiece, which has been the driving force behind the brand since the beginning.

The whole back of the Ressence Type 3 replaces the crown

The first shift saw the entire case back and rear bezel used to manipulate the watch with two rings, one to indicate what function you have selected, and the other to allow specific movements to wind, set the time, and set the date. Using a gravity clutch for engagement, the time setting only functions in one orientation, adding another layer of complexity and an entire dimension to the interaction experience.

The second shift introduced the e-Crown, a fantastic automatic electronic system that couples with the mechanics inside. Both of these developments illustrate that the brand is committed to the idea of interaction and taking continuous steps to create change.

People have been very clever to update and improve upon the keyless works to make them more robust, precise, and capable, but often that is where it ends. For others, just making a nice, straightforward crown is all that is attempted.

Design risks not taken

I find it interesting that one of the most incredible watch brands in history, Greubel Forsey, makes timepieces that break boundaries and set records, yet utilize such a relatively boring watch crown.

The simple, square, fluted design is nearly ubiquitous across the industry, and on every Greubel Forsey timepiece you find it just hanging out on the side of the watch, almost like it doesn’t want to rock the boat even though this brand makes outrageous asymmetrical watches that can make the most adventurous collectors question its decisions.

The crown is one of the most mundane features on a Greubel Forsey watch, which shows that no matter how expensive and well made a watch is, trying interesting things with the crown is not a widely practiced endeavor.

And when you look across the industry, you find that nearly all brands tend to fall into the same category when it comes to the watch crown, following one of about three or four basic designs: square fluted, onion/tapered, square with cabochon, or thin with slight rounding.

Out of the 195 watches entered into the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie in 2018, only around 15 strayed from those designs enough to be considered different, and most of those were due to being jeweled or shaped to continue design elements elsewhere in the watch.

Only a handful have any interesting way to interact with the watch outside of a regular crown mechanism, and one of those is the Ulysse Nardin Freak.

If we assume the entries into the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie represent a decent smattering of the industry (which I would say it very well does), then only around two to seven percent of watches attempt anything other than the most basic watch crowns, and definitely less than two percent are daring enough to invent something different.

Jet reactor-themed crowns on the MB&F HM4 Double Trouble

And I might even venture a guess that that is highly skewed due to the relatively low number of watches in the competition. If we really looked at the total percentage of watches in production every year, the number of watches that attempt anything different for the crown probably drops to less than 0.02 percent of the total.

It just isn’t done. And that means there is incredible potential for trying something new, and watch companies are totally missing it. The companies will spend millions developing incredible complications and technologies, but they leave the humble crown alone, probably because they think it is the simplest and easiest solution to a problem.

It might be, but since the entire purpose of watches has changed from truly utilitarian objects into objects of passion and ingenuity, then why not work a little more with that area? Tradition is a hard parent to abandon.

So are watch crowns boring?

Well, no, they are just largely standardized because they are pretty complicated in their own right. I can understand why most stay the same, but I also want creativity. And I see so much room for it from established brands and independents alike.

Definitely not boring: the oversized diamond-set crown of the Urwerk UR-106 Lotus White

Yet wanting to see something new does not diminish how incredible and crucial a crown is to the function of a watch.

If it weren’t possible to perfectly seal a watch against the elements, many of the mechanical risks that companies take with movements, research, and development would be for naught in a case that couldn’t protect them.

The standardized (and somewhat stale) watch crown makes modern watchmaking possible. And it does so with a quiet persistence that makes it easy to overlook how incredible and important it is.

It might not usually be the flashiest feature on a watch, but it is nevertheless one of the components a watch owner interacts with most, helping to protect the investment for years to come.

Even a boring crown can be regal

I think the watch crown is the unsung hero of the watch industry, and I would hope that more watchmakers might work to highlight it because it has been working tirelessly for a century and a half to protect that which we hold dear.

* This article was first published December 8, 2018 at Here’s Why The Crown Is The Unsung Hero Of Watchmaking (And Why Rolex Wears The Crown).

You may also enjoy:

Romain Gauthier Celebrates Ten-Year Anniversary With HMS Ten

Here’s Why A Watch Strap Is More Than Just An Accessory

Ballon Bleu De Cartier Moon Phase: Once In A Blue Moon

Ressence Type 2 e-Crown Concept: The Right Combination At The Right Time

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

You can say what you want about “the crown” and pontificate about the tactile sensation one gets when touching the one part of the movement that is presentable. But the fact remains that it’s a moot point when manufactured scarcity and unscrupulous ADs prevent the act from happening in the first place. So, the refrain remains the same; BOYCOTT rolex.

Hi Ron. You seem frustrated not to be able to get your hand on a particular model from “the crown”. I suppose that if these are not “for sale” in ADs to normal human beings, then one may opt to select a different model/brand. Quite a few provide a great tactile experience when winding. Others, like my Lecoultre futurematic don’t have a crown at all. 🙂

👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻

Great read! For what it’s worth, and as an owner of many luxury watches (including six of “The Crown”), Omega has the BEST – hands down – crown/stem assembly.

Hi. As you are clearly a collector, you may want to try to locate a JLC reverso 8 days and wind it. It does top my omegas.

I love my Omega watches, but the crown does not compare to my Rolex watches. The attention to detail in how the crown allows for grip alone puts Rolex at the top.

I could barely unscrew and wind my Aqua Terra.

I just passed on the new Breitling Chronomat 42 B01 with the bullet bracelet because the crown was impossible to unscrew and wind.

When one rotates between multiple watches, the crown function becomes even more important.

What about the IWC and the big pilot crown. An oversight?