5 Things You Should Know About Port Wine But Probably Don‘t, Including Why You Don’t Want To Know The Bishop Of Norwich

by Ian Skellern

The Portuguese city of Porto has been on a roll over the last few years, with its popularity ramped up even more after being voted Best European Destination for 2017, an award it also won in 2012 and 2014. The town’s rich cultural heritage, fantastic food and wine, alluring climate, relative proximity to most of Europe, and ease of access thanks to a big new airport make Porto a very attractive destination.

So when Elizabeth Doerr and I were recently invited to visit the workshops of Eleuterio, the world’s leading specialist in traditional Portuguese filigree jewelry, which is based near Braga just to the east of Porto, we not only accepted with pleasure, we took our spouses and extended our stay with a weekend in Porto.

Drinking Port in the port of Porto

There are a plethora of places to see in Porto − the city center is a UNESCO World Heritage site − but one absolute must for wine aficionados is to spend a couple of hours across the river Douro in Vila Nova de Gaia visiting a Port house and tasting the wines.

Looking from Porto across the Douro river to the Port houses in Vila Nova de Gaia

There are many to choose from, but do check in advance for tour times as they are not as frequent as you might expect in every language. My wife and I ended up at Quinta dos Corvos, a small upscale producer, and enjoyed both the visit and wine tasting immensely.

While the informative tour and tasting at Quinta dos Corvos (and I’ve no doubt everyone else too) is obviously designed to impart knowledge to encourages sales − and in our case mission accomplished −I found the story of Port wine, aka vinho do Porto, fascinating and hope you do too.

5 things about Port wine you may not know

Port wine vineyards in the Alto Douro (photo courtesy www.dourotours.co.uk)

1. Port wine doesn’t come from Porto

The grapes are grown and the wine is produced in the Upper Douro Valley (also a UNESCO World Heritage site), which is around 100 kilometers east of Porto.

Rabelo boat once used for shipping Port wine to Porto from where it was grown up river in the Alto Douro

While the wine was transported down the Douro river on photogenic Rabelo boats until around 50 years ago, less romantic but more practical road transport has dominated since. Porto is the city from which the Port wine was shipped to England, so the wine was widely known as coming from Porto.

2. Port wine as we know it today was invented specifically for the English

This soundly explains why so many of the big Port brand names are English; for example, Taylor’s, Graham’s, Dow’s, and Cockburn’s.

Inhabitants of the region that is now northern Portugal have been making wine for at least 2,000 years, but the signing of the Treaty of Windsor in 1386 created an enduring political, military, and commercial alliance between England and Portugal giving the merchants of each country the same rights as the other to reside in its territory and trade on equal terms. Commerce blossomed, increasing even more in 1654 when the Anglo-Portuguese commercial treaty created new opportunities for English and Scottish merchants living in Portugal, allowing them special privileges and preferential customs duties.

Then, in 1667, France under Louis XIV began restricting the import of English goods, which provoked Charles II of England into increasing the duty on French wines and later forbidding their import altogether. This obliged the English wine trade to seek alternative sources of supply, and the English merchants in Portugal seized the opportunity.

While wine was made all over Portugal, the British preferred the fuller-bodied wines of the upper Douro Valley in the hinterland of Porto, so the city became an important center for the trade.

While a little brandy had been added to the Port wine to reduce spoilage on the long transport to England for centuries, it wasn’t until the nineteenth century that the practice of adding brandy to stop fermentation became popular. Fermentation is the metabolic process of converting sugar to alcohol, usually by yeast (a live single-celled fungus).

Adding brandy during fermentation when the alcohol level reaches around 7 percent kills the yeast before all of the sugar is converted, resulting in a sweeter wine with low alcohol level fortified by brandy (19.5 percent alcohol is common for Port wine).

However, the sweetness is just a fortunate byproduct of the process; the main aim in creating fortified Port wine was to enable it to be aged for much longer, a process significantly improving the quality of the wine, which was generally much rougher when young than the wines we enjoy today.

3. There are three main types of Port wine: Ruby, Tawny (red and white), and Vintage

A relatively affordable young Ruby Port by Porto Valdouro

Ruby: The wine is aged in oak casks for between 18 months and three years, perhaps with the addition of older vintages for balance, before being bottled. It’s then ready to drink as a young and fruity sweet wine. It’s worth trying a glass, but Ruby isn’t where the action is.

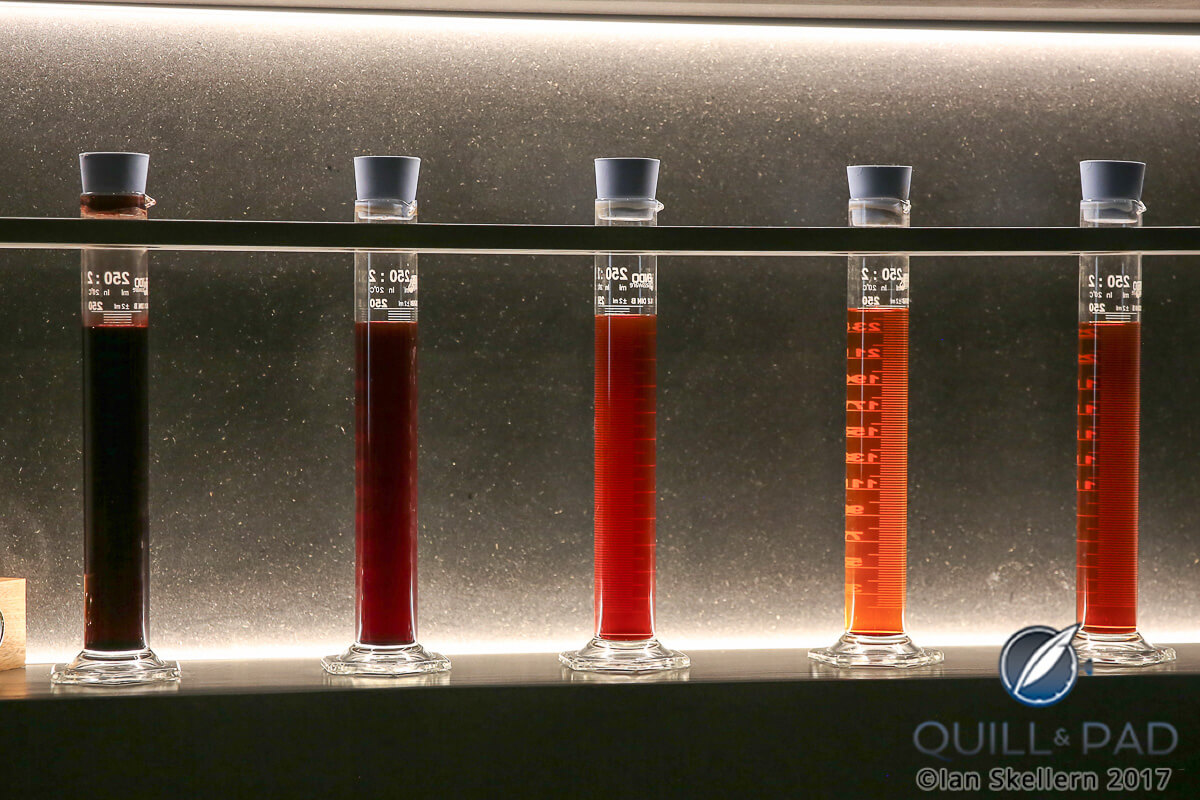

20, 30 and 40-year-old Tawny Port by Quinta dos Corvos

Tawny (white and red): Wine from a full decade of vintages is blended and aged in casks for periods of 20, 30, or 40 years before being bottled. A 20-year-old Tawny will have wines from 20 to 29 years old; a 40-year-old will have wine from 40 to 49 years old. The reason that the oldest Tawny wines stop at 40 years is that the oak casks are not sure to last for 60 years (a 50-year-old Tawny would contain wine up to 59 years old).

The older the Tawny, the rounder and smoother it is and the more caramel and butterscotch notes (from the wood) it exhibits. A good 20-year-old Tawny is superb; a good 40-year-old Tawny is divine.

Tawny (and Ruby) Ports age in their casks but do not age in the bottle, so they can be stored for decades if not centuries. A bottle of Cockburn’s from 1864 drunk recently was reported to be excellent.

Even once the bottle has been opened, Tawny Port can easily last up to a couple of years. Vintage Port, on the other hand should, be drunk within two to three days after opening the bottle (though I’ll bet it will be finished well before then).

Well-aged Vintage Ports (photo courtesy Jared Greenhill/Wikipedia Commons)

Vintage: Like vintage champagne, vintage Port is only made from the grapes of a single exceptional year. Unlike Tawny Port, which is oak-aged for 20 to 50 years before bottling, the wine for Vintage Port is aged in a cask for around two years and then bottled. Vintage Port then continues to age in its bottle like a fine wine and is best enjoyed after decades in the cellar rather than years.

We tasted a 1996 Vintage Port from Quinta dos Corvos and were blown away. Even in the rare exceptional years that Vintage Ports are made, only a tiny percentage of the wine is used to make Vintage wine so very little is exported. In fact, few people know that Vintage Port even exists.

If you can find a bottle I highly recommend trying it, but be warned: like any fine old wine it is unlikely to be cheap.

4. Red and white Port wines exchange color as they age

One interesting factoid is that, paradoxically, red Port gradually becomes clearer as it ages in the cask, while white Port wine becomes darker.

Tawny Ports left to right: 20-year-old red, 30-year-old red, 40-year-old red, and 30-year-old white

A 30-year-old red Tawny and a 30-year-old white Tawny are virtually indistinguishable in both color and taste. It is the rich red becoming a paler, more amber hue that gives the wine the name “Tawny.”

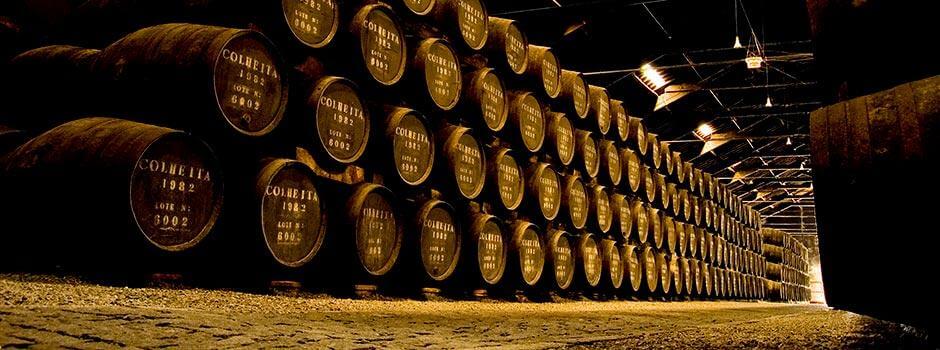

5. The casks are as interesting as the wine

What a life the casks used in the making of Port have; what travels they undertake: and what a variety of sensational drinks they help make. While cheaper Port producers use oak chips in stainless steel tanks, the best start with new oak casks that they carefully manage in rotation for up to 50 years. But that’s not the end of their lives.

Port wine casks just starting their lives (photo courtesy www.visitar-porto.com)

After decades of aging Port, the timber of the casks is infused with complex compounds from the wine, and the raw oaky flavors have leached out. And that just happens to be perfect for the distillers of Scotland, Ireland, and the USA, where they are in high demand for finishing the aging of whiskey and bourbon.

A soupçon of port in your whiskey, sir?

Those of you who enjoy nicely aged Scottish whiskeys can thank the Port and/or Madeira wine-flavored casks that help enrich its smooth, subtle aromas.

Then there’s the Bishop of Norfolk and Port-passing etiquette

When Port is passed around at British meals, tradition dictates that immediately after pouring a glass for his or her neighbor on the right, the decanter is then immediately passed to the left. So you do not pour your own drink but that of your neighbor to the right. You then pass to your neighbor on the left, who fills your glass and passes to their left. The decanter doesn’t stop its clockwise progress around the table until it is finished.

Tradition states that Port should be passed to the left until the decanter is finished (photo courtesy www.thegentlemansjournal.com)

If someone breaks the flow or otherwise breaks tradition, the breach of etiquette is brought to their attention by asking, “Do you know the Bishop of Norwich?”

The origin of the story is usually attributed to Henry Bathurst, who was Bishop of Norwich from 1805 to 1837. The Bishop lived to the ripe old age of 93, however in his later years suffered from poor eyesight and a tendency to fall asleep at the table, especially (and understandably) toward the end of the meal when the Port came out.

As result, the Bishop often failed to pass the Port on to the detriment of those seated further up the table.

Passing a bottle, or preferably a decanter, of fine Port around the table at the end of an enjoyable meal with friends is becoming less common these days, but I’d suggest that (unless driving) it makes for a mellower end to the evening than the now ubiquitous coffee.

Saude!

* This article was first published on May 15, 2018 at 5 Things You Should Know About Port Wine But Probably Don‘t, Including Why You Don’t Want To Know The Bishop Of Norwich.

You may also enjoy:

Teeling Whiskey: The World’s Best Single Malt, And That’s Official

Wild Turkey Master’s Keep: A Great Bourbon For Drinking Now

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!