The 180th anniversary of Dresden’s famous Semper opera house takes place in 2021.

Dresden Semper Opera House

Home to the Saxon State Opera and the Saxon State Orchestra concert hall, the 180-year-old building is renowned for its beautiful baroque architecture and impressive history of premieres, including major works by Richard Strauss and Richard Wagner.

Since the opera house’s inaugural performance on April 12, 1841, the Semperoper (as it’s known in German) has delighted its audience with first-class concerts and operas and a sophisticated showcase of a more technical nature: a clock with an extra-large digital time display in five-minute increments, the aptly named Five-Minute Clock, which hangs over the stage.

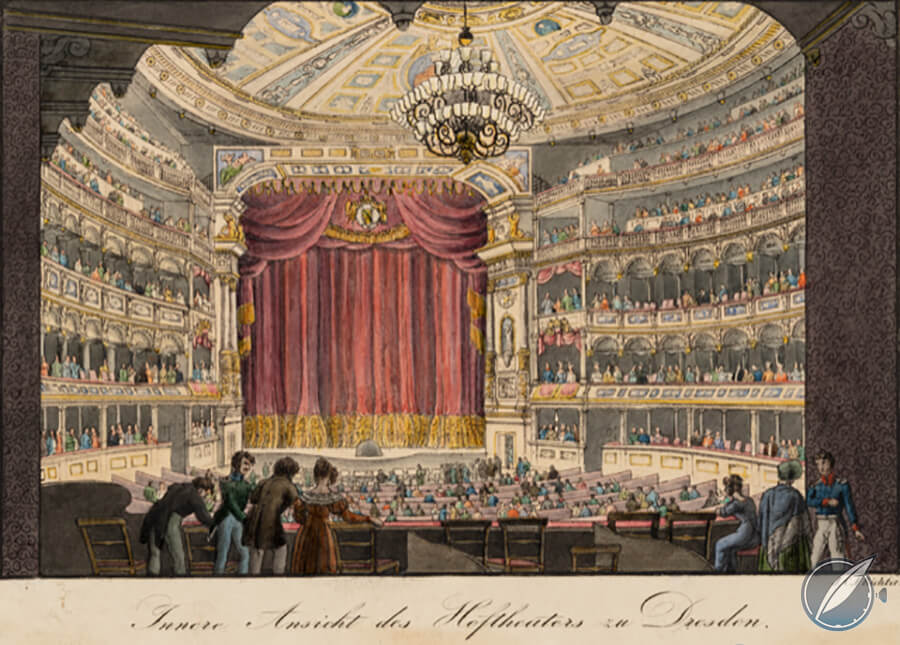

Inside the Dresden Semper Opera House circa 1850

Such a large-format presentation, readable at a glance even from the theater’s back rows, was huge in a literal sense and marked a milestone in clock technology. The innovative design proved to be so ingenious that it would be rebuilt twice and resonate into modern times.

Five-Minute Clock above the stage at the Dresden Semper Opera House

Destroyed two times through fire (1869 and 1945), it was restored to its former glory by ingenious clockmakers and engineers.

A. Lange & Söhne Lange 1’s large date was inspired by the Five-Minute Clock at the Dresden Semper Opera House

And some 30 years ago, just after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the clock served as inspiration for the famous A. Lange & Söhne Lange 1 wristwatch, which played a significant role in the renaissance of Glashütte’s fine watchmaking.

Today, the Five-Minute Clock both tells the time again in the Semper Opera house and takes center stage on the wrist of A. Lange & Söhne enthusiasts.

Squaring of the circle and a gem of Saxon clockmaking

Located on the banks of the river Elbe, in the mid-nineteenth century Dresden was an important location, not only in terms of the arts and modern life, but also in the fields of science and research. As it was the case for many noble courts around the world, the Saxon monarchs had a penchant for science, art, and progression – and had the money for cutting-edge technical instruments, which they liked to boast about.

In 1724, the Mathematics-Physics Salon, featuring a collection of precision clocks, musical clocks, astronomical models, and telescopes, was founded, which since 1728 has been housed in the Zwinger, a famous baroque building complex with gardens in the heart of the city. Along with the Frauenkirche and Semperoper opera house, the Mathematics-Physics Salon is one of the best known landmarks of Dresden.

When the construction of the new opera house was commissioned, the Saxon court assigned Johann Christian Friedrich Gutkaes – trained astronomer, mathematician, and highly skilled clockmaker – “to create a clock that the world had not seen before – a curiosity among its kind.”

This oeuvre had to meet the high demands of the art of Saxon watchmaking and “to be as accurate as a chronometer.”

Although Dresden’s clockmakers guild, of which Gutkaes was an important member, was known for high precision and excellent workmanship even beyond the borders of the city, designing a timepiece of such sheer size and capable of high accuracy was a major challenge.

Rebuilt mechanism of the Five-Minute Clock at the Dresden Semper Opera House

Gutkaes opted for a design consisting of two cloth-covered rollers with large printed numerals. They were driven by a gear train and framed by a panel with two prominent windows. The left one displayed the hours with Roman numerals I through XII, while the right indicated the minutes in increments of five using the Arabic numerals 5 to 55.

The rollers, which measure about 160 centimeters in diameter, allow for the creation of numerals about 40 centimeters high and legible all the way to the back rows, even when it was dark in the theater during the performances.

The space offered by the proscenium – the part of the theater stage in front of the curtain – above the stage would not have been sufficient for a similarly easy-to-read analogue display, so Gutkaes’ brainchild was the best possible solution.

And it was groundbreakingly new to have a time indication using numerals and no hands. Almost like the squaring of a circle. It’s worth mentioning that Gutkaes designed and built the Five-Minute Clock together with his student, later partner, and son-in-law Ferdinand Adolph Lange.

The Semperoper has risen like a phoenix from the ashes – twice

In 1869, the Semperoper and the stage clock were completely destroyed in a fire. When the building was reconstructed, Ludwig Teubner, an apprentice and employee of Gutkaes who was familiar with the original design, was commissioned to make a new stage clock.

His clock was based on the Gutkaes original and combined the elements of traditional tower clock construction with those of classic clockmaking. It was produced in Teubner’s workshop and the Zachariä tower clock factory from Leipzig. Teubner, his son-in-law Ernst Schmidt, and Schmidt’s son Felix maintained the second clock across three generations, so the knowledge of its technology was preserved until well into the twentieth century.

The operating principle has also been kept alive thanks to a masterfully executed 1:10 scale construction model that is today on display at the Mathematics-Physics Salon in Dresden.

The Semperoper was completely destroyed once again in World War II during the bombing of Dresden in 1945, and a new clock was later commissioned in 1979 as part of the second reconstruction.

The Five-Minute Clock above the stage at the Dresden Semper Opera House

Based on Teubner’s construction model, the team of experts led by engineers Klaus Ferner and Harry Julitz reconstructed the Five-Minute Clock to its former glory. Carried out in accordance with the preservation of historical monuments, it was installed in February 1985 after the building had been completed, and has since delighted music and clock enthusiasts alike.

A. Lange & Söhne large date: a symbol of the renaissance of Glashütte’s fine watchmaking

A few years later it once again played a starring role, however in a very different timepiece. As watch lovers in general and Glashütte enthusiasts in particular are well aware of, Walter Lange, great-grandson of Ferdinand Adolph Lange and great-great-grandson of Johann Christian Friedrich Gutkaes, revived his family business right after Germany’s reunification in the early 1990s.

The famous name A. Lange & Söhne had been on involuntary hiatus for more than 40 years in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), better known as East Germany.

Hartmut Knothe (left), Walter Lange (center), and Günter Blümlein at the launch of A. Lange & Söhne in 1994

On October 24, 1994, Walter Lange and business partner Günter Blümlein presented the first four timepieces of A. Lange & Söhne’s new era to a select audience in the Dresden Castle.

A. Lange & Söhne Lange 1 against the backdrop of Dresden’s Semperoper

Among the four new wristwatches was the now iconic Lange 1. As a nod to the noble tradition of Saxon watchmaking and to founding father Ferdinand Adolph Lange, its two-window large date was inspired by the Semperoper’s stage clock.

Together with the signature off-center dial layout, which was designed to the proportions of the golden ratio, this famous hallmark has been a part of all Lange 1 models since then, and is considered a symbol – if not the symbol – of the fine art of contemporary Glashütte horology.

This piece of mechanical ingenuity was the modern A. Lange & Söhne’s first patent filing and kicked off a new large date trend. Since then, we have seen many refined designs from prestigious brands, including the Panorama Date from Glashütte Original that foregoes a mullion between the two numerals.

Lange 1 by A. Lange & Söhne

However, the most appealing large date to me remains the A. Lange & Söhne through two framed windows. I love the slightly playful yet distinctive font of the deep black Arabic numerals against the white background, especially when the two and five are on display because their serifs are the boldest ones.

For more information, please visit www.semperoper.de and/or www.alange-soehne.com/en/timepieces/lange1.

You may also enjoy:

175 Years Of Watchmaking In Glashütte: A History Of Fine German Watchmaking

How The Wall Came Tumbling Down: Made In Germany

A. Lange & Söhne Lange 1 25th Anniversary Edition: Celebrating A Quarter Century Of Asymmetrical Cool

‘Made In Glashütte’ Vs. ‘Made In Germany’: What Puts Them Together, What Sets Them Apart

Made In Germany: The Glory Of Glashütte

The Life And Times Of A. Lange & Söhne Re-Founder Walter Lange

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!