Trinity Hill Homage Syrah: A Strong Contender For New Zealand’s Best Wine

by Ken Gargett

People will make “best of” lists for as long as we exist. It seems key to our very DNA.

So here is one. New Zealand’s best wine? It is going to be a red – Bell Hill’s magnificent Chardonnay, at times reminiscent of Montrachet, should be a contender, but as Bell Hill makes about six bottles a year, I’ll put it to one side for now.

So surely a great Pinot Noir, and there are many from which to choose. What about a Syrah? One of the greats from the Gimblett Gravels? Craggy Range’s Le Sol? Perhaps Trinity Hill’s stunning Homage?

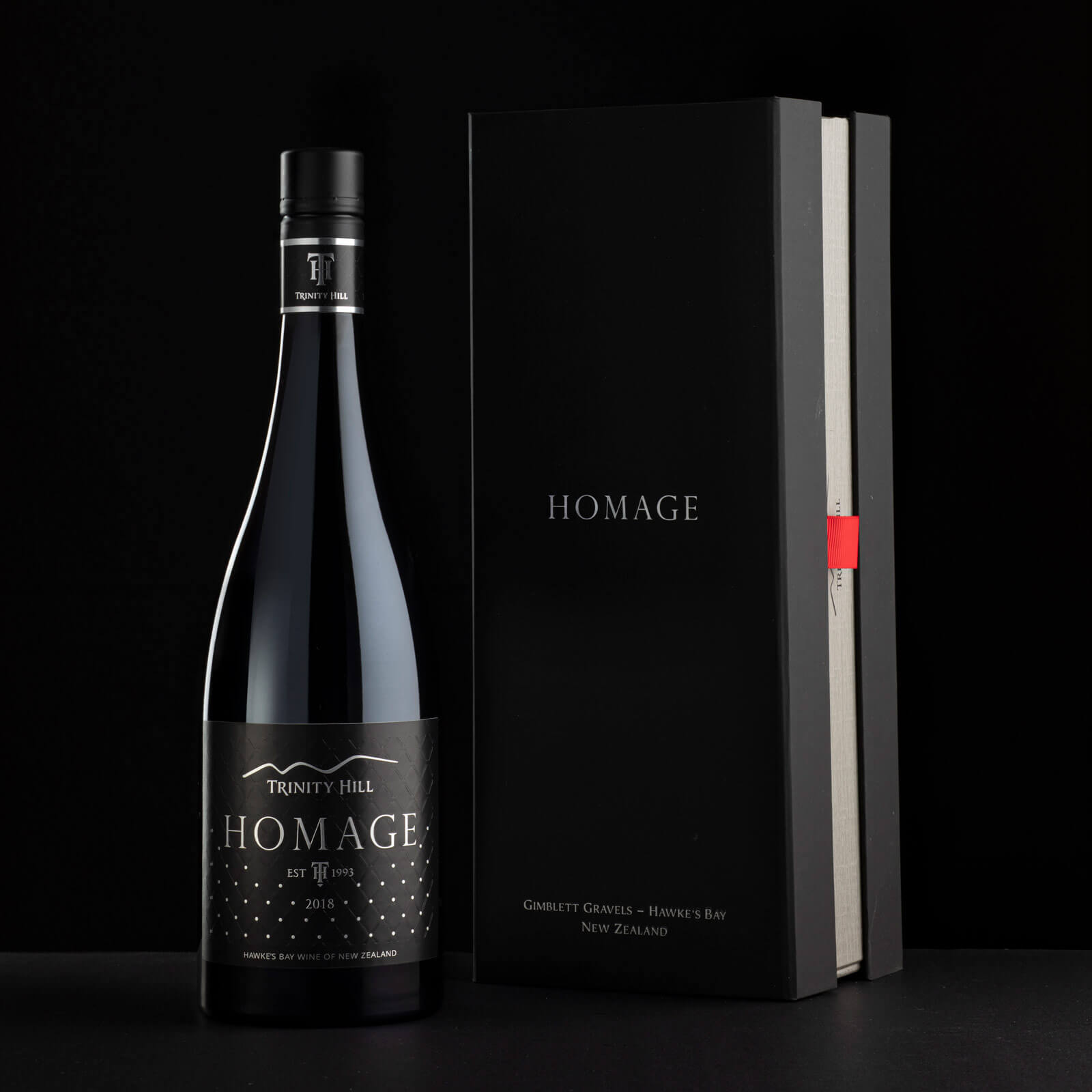

Trinity Hill Homage 2018

As it happens, there is plenty of support for the claim that Homage is indeed New Zealand’s best red. My heart tells me that surely it must be a Pinot Noir – Ata Rangi, Bell Hill, Felton Road, and others all spring to mind; Pinot has that effect on people – but my head tells me that that just might be right. Homage is a cracking wine, brilliant year after year.

Syrah is basically a minor variety in New Zealand. Figures from 2021 suggest that there are 40,323 hectares of grapes grown throughout the country: 32,493 of those are white (Sauvignon Blanc is a whopping 78 percent of that, so it is easy to see how crucial the success of that variety is for New Zealand).

Of the 7,830 hectares devoted to red varieties, 73 percent of that is for Pinot Noir and 14 percent for Merlot. Just six percent is Syrah (by my math, that means just 470 hectares are Syrah – basically a drop in the ocean).

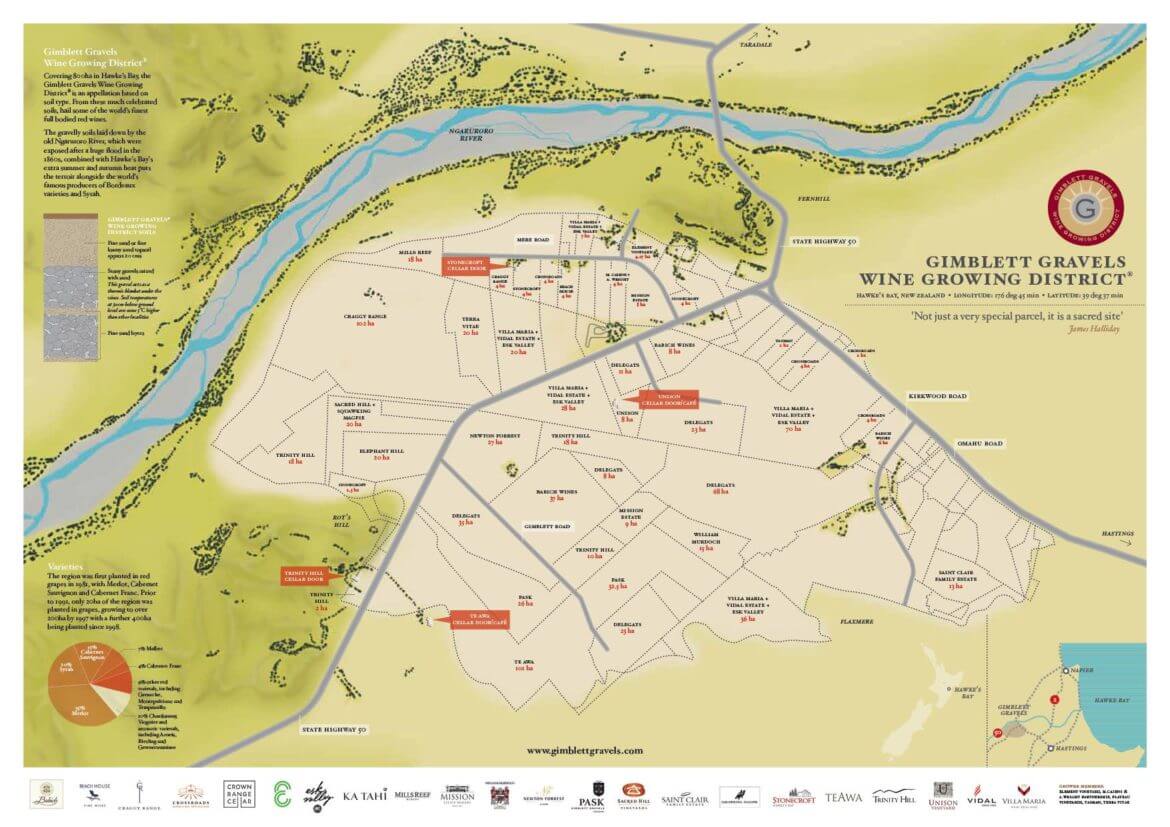

The majority of that is found in Hawke’s Bay, but even there it falls in the shadow of both Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon. Hawke’s Bay has 4,643 hectares under vine, with only 800 hectares of that forming the Gimblett Gravels subregion.

Homage is a 100 percent Syrah (or Shiraz, if you prefer) from the highly regarded Gimblett Gravels subregion of Hawke’s Bay, made by Trinity Hill. Current winemaker is Warren Gibson, who worked with, and followed on from, the original winemaker, John Hancock, an Australian ex-pat (and who knows Shiraz better than Aussies? – yes, I am certain that many will claim to).

About Gimblett Gravels

Only 800 hectares in size, Gimblett Gravels is one of the newest wine regions in the world in every way. It didn’t even exist until nature took a hand – which shows how precarious so many other regions around the globe might be.

Map of the Gimblett Gravels wine-growing district, Hawkes Bay, New Zealand

In 1863, Hawke’s Bay suffered a severe earthquake. Nature was not finished. In 1867, the Ngaruroro River, which runs through the region, flooded to the extent that the river was redirected, not least thanks to the destruction wrought by the quake. This left a patch of gravel uncovered.

Welcome to the Gimblett Gravels. Of course, what nature giveth, nature could very easily take back, especially in New Zealand. But until that happens we’ll continue to keep our fingers crossed for the region and enjoy the wonderful wines it offers.

The region had more problems ahead: if nature is tough, people can be infinitely more difficult.

In 1982, Alan Limmer established a vineyard called Stonecroft in the worthless gravel (suffice it to say, things have changed a little and this is now some of the most expensive vineyard acreage in New Zealand) surrounded by a rubbish dump, a drag-racing strip, an army rifle range, and a quarry. The gravels appeared infertile and were obviously stony.

Limmer, however, had another profession other than winemaker. He was a soil scientist.

Limmer was keen to build a winery for his vineyard, but the local council decided otherwise, refusing permission, which kicked off a long and intricate saga of appeals and litigation.

After he lost his attempt to gain permission for a winery, finally overturned and not in his favor, Limmer went big. He sought permission to have the entire, albeit small, region zoned for viticulture. By this stage, the quarry had expansion plans of its own and it was back to court for everyone.

It was not until 1992 that Limmer finally prevailed. Until then, no one else had joined the charge to plant vines, but as soon as victory was achieved wine became the focus, land prices soared, and I doubt that there is space to stick a single extra vine in the ground today.

Gimblett Gravels vineyards in autumn

Fair to say that there are not many wine regions that exist solely because of the efforts of one man, but the Gimblett Gravels is one – that said, of course others have been involved, not least CJ Pask, who purchased land he’d spotted from a flight in 1981.

The region is heavily focused on reds, mostly Merlot and Cabernet. Syrah was a tiny percentage in the early days. The first vintage of Limmer’s Stonecroft was 1987, and Stonecroft also produced New Zealand’s first Syrah of recent times in 1989, which came from vines Limmer planted in 1984, making them the oldest Syrah vines in New Zealand.

Limmer got the vines from research stations. It is believed that they were originally imported from Australia around 1900.

Cabernet and Merlot dominated for the early years but as the sheer quality and exuberance of the Syrah became apparent, plantings have increased. There is still argument about which variety is the true star in Gimblett Gravels/Hawke’s Bay, but for me – looking at wines like Homage, Craggy Range’s Le Sol, Sacred Hill’s Deerstalkers, Bilancia’s La Collina (which is the private vineyard of Trinity Hill winemaker Warren Gibson), and many others – Syrah gets my vote.

Trinity Hill

Trinity Hill came about when John Hancock met Robyn and Robert Wilson, owners of the Bleeding Heart restaurant in London, in the late 1980s. Their idea for a winery back home in New Zealand, largely conceived over a bottle of Hancock’s Chardonnay, came to fruition in 1993 when they established Trinity Hill in the Gimblett Gravels, making it one of the earlier operations.

Trinity Hill winery

Hancock joined in time for the first vintage, 1996. The Wilsons finally sold the estate early in 2021 to four New Zealand investors. At the moment, it seems business as usual (why on earth fix what isn’t broken?).

Their grapes had been planted on the barren dirt that had once formed the bed of Ngaruroro River. The initial 18 hectares was followed in 2000 with a further 20 hectares. The soils are deep river shingle. Exposed greywacke gravel stones release the heat they absorb. They also offer ideal free draining conditions. Homage is not a single-vineyard wine but rather the grapes are sourced from three discrete vineyards.

The inspiration for Homage came after a visit Hancock took to the legendary Rhône maker Gerald Jaboulet, who made the famous Jaboulet Hermitage La Chapelle. These days it is still fabulous but probably not quite the wine it once was.

That said, La Chapelle from vintages such as 1990, 1978, and 1945 are all some of the greatest bottles I’ve ever tasted (the 1961 is right up there, in reputation, as one of the greatest wines ever made in the Rhône, but sadly yet to cross my path).

Hancock was so impressed by his visit that he arranged to work at the estate in 1996. Gerald Jaboulet sent him a parting gift, three plant clones of Syrah and one of Viognier. Sadly, Jaboulet passed away the following year. Hancock had the vines quarantined and propagated – and by 2002 planted them in the same vineyard that held Syrah vines from cuttings from Stonecroft.

Trinity Hill made its first Syrah in 1997 and its first Homage in 2002, so no involvement from those clones from Hermitage at that stage. The estate makes several Syrah wines but Homage is the flagship.

It is worth stressing that there are a number of excellent wines from Trinity Hill but today I am focusing on the Homage. It is only made in vintages deemed suitable. Yes, everyone says that, but these guys have only released around 60 percent of the years since it was first made, providing compelling evidence that they are indeed extremely careful to ensure that only those wines deserving appear under the Homage label, though lately it has been almost every year – deservedly so.

The vintages released so far include 2002, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2010, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018. One suspects conditions in 2019 and 2020 will see Homage from those years as well.

As mentioned, it was ex-pat Aussie John Hancock who set this winery, and wine, on its stellar course. He moved from South Australia in 1979, joining Delegat’s in New Zealand and specializing in Chardonnay. He moved to Morton’s in 1983 and produced New Zealand’s first whole-bunch pressed, barrel-fermented Chardonnay.

He moved to Trinity Hill in 1996 and has said that the very first Homage – the 2002 – is the best wine he has ever made. Hancock moved on from Trinity Hill in 2018, keen to get back into more hands-on winemaking.

As almost always happens when someone so closely linked to a winery, let alone such a force of personality, moves on, the reaction is one of doom and gloom, impending failure. Which is of course almost always also rubbish.

Warren Gibson, chief winemaker at Trinity Hill winery in New Zealand

Warren Gibson, current winemaker, might not be able to claim an Aussie heritage but he did study there, at the famous Roseworthy College, before joining Hancock at Morton and then following him to Trinity Hill in 1997. He is as much a fixture, and as essential to the success the place has enjoyed, as Hancock.

Trinity Hill Homage

As many wine lovers around the world will know, the vast majority of Kiwi wines are under screwcap. I am a huge fan of that form of closure, and New Zealand committed itself very early, just a year or so after Jeffrey Grosset and other Clare Valley makers revived it. The entire production of Trinity Hill has been under screwcap since 2013 with one exception: the Homage.

So often, the last wine to move to screwcap is an estate’s premium offering. There are two ways to look at this. One is that the winery has taken extra care researching and trialing closures to ensure that the best option is chosen, and I am sure that is the case here (although Gibson has also conceded that “market pressure was an influence”).

The other is that marketing departments and corporate bean counters are terrified that they will lose buyers internationally if they move to screwcap (no names, but I’m looking at you, Penfolds Grange – pure speculation on my part, I should add), even though winemakers will often privately express a wish that cork be relegated to trivia evenings and nostalgia nights.

Trinity Hill Homage 2018

With the 2018 Homage, Trinity Hill has moved that wine to screwcap, joining the rest of the portfolio. This was anything but an overnight decision or a kneejerk reaction. Trinity Hill has been running trials since 2000. Gibson has been quoted as saying, “Why? Quite simply, it is a better wine for it, both now and in the future.” Hard to argue.

As well as avoiding the dreaded cork taint, which the Portuguese, to their credit, have done considerable work in reducing, Gibson found other benefits: a smoother mouthfeel; better color; more openness; less SO2 (sulfur dioxide) evident; and a wine open to earlier drinking but aging just as well.

It has been fascinating to watch the evolution of Homage and the impression it has made as more and more of the world’s critics have discovered it. It seems every release is hailed as “best ever.”

I’ve tasted some early vintages, though not many, but it was after judging once or twice in New Zealand many years ago (with Gibson, if that somewhat unreliable memory serves me well on this occasion), the first thing I did when I got home was to chase my local wine store for a few bottles of the then current Homage.

I have tried to pick up one or two every now and again, but it is not always easy to find. A thorough search of retail outlets across Australia revealed just one with stock of the 2018 only. Not another bottle anywhere! It was selling for just under AUD$200, which in the scheme of things is great value, given where this wine sits in comparison to other flagships.

What is the level of production? I have seen it quoted as just 600 bottles a year, so my thoughts are to grab whatever you find (and don’t hesitate to pick up any other wines from this estate). Other estimates fall between 100 and 500 cases, depending on the vintage. Around 80 percent of that is exported.

There have inevitably been changes in the winemaking over the years. Perhaps most notable was that the bottle was once the sort of thing that could have been used for training by bodybuilders, so heavy was it. Now it is still impressive, but certainly lighter – a good thing.

As for the wine, it was once matured in 100 percent new French oak but that percentage has been reduced to the benefit of the wine. A percentage of whole bunches has been included since the 2013 vintage. The grapes are handpicked.

Obviously, each vintage will vary due to the exact details of the winemaking, but a general example is around 60 percent destemming, a light crushing, with the remaining 40 percent fermented as whole berries. The 2018 was less than this at 25 percent.

The cap will be plunged by hand and/or there will be pumping over twice daily. Expect around a month on skins, though it can be considerably longer for individual parcels. Around 14 months’ aging (as noted, mostly but not entirely in 100 percent new French oak). Some of the wine spends time in 5,000-liter oak ovals. The wine is not racked while in barrel, but there might be some stirring.

Over the course of this virus-infected year, I’ve pulled a few of my remaining bottles of Homage out of the cellar to share with friends, and the estate kindly sent me some fascinating bottles to taste as well.

Most intriguing was a pair from 2010, one under cork as released and the other one of the trial bottles under screwcap. Gibson has noted the freshness of the screwcap-sealed bottles and while some of those under cork have performed exceptionally, there has been much more variation. My bottle under cork was superb, though just pipped by the screwcap.

After I had tasted the wines thoroughly, I took them along to a lunch with wine-obsessed friends and served them blind along with a 2014. The universal response (other than that showing the same wine under two different seals was an act that would not be perpetrated by a gentleman) was that the 2010 bottle under screwcap was the youngest in the lineup.

Both from 2010 were preferred over the 2014. A few months earlier, I’d tasted the 2017 under cork and 2018 under screwcap, as they all are. Both were also stellar.

Trinity Hill’s Homage is a wine that should be in every serious wine lover’s cellar. They get better and better. New Zealand’s best wine? It is right up there.

Trinity Hill Homage tasting notes

2010 (cork): Blood red in color. Real complexity here. Dry herbs, florals, spices, a whiff of pepper, leather, animal hides, game, truffles, licorice, and some delicatessen notes. Great stuff. Loved this.

Supple and seamless. Very fine and soft tannins here. Still with wonderful life and vibrancy in it. There is development, certainly, but still fresh and bright. Cracking wine, whatever the closure. 97.

2010 (screwcap): The colors here were extraordinary. Over a decade in age and they were purples and bright crimson. The wine was fresh, floral, bright, and vibrant. Real vitality evident.

Plums, truffles, exotic spices, and more red fruits apparent here. Lovely complexity. Seamless and plush. There are the silkiest of tannins. A wonderful wine with a very long future. Complete and complex. 98.

2014 (cork): Aromatic. Black fruits and plums. Cloves, leather, spices, and fennel. Good complexity here. It took time to open. Slightly gritty tannins. Good concentration and excellent length.

This was quite Rhône-like, more so than any other in the lineups. Notes of salami and dry herbs emerged. Some mulberries, violets, and florals. This did not score quite as highly as the others, largely because the tannins were more grippy and the wine seemed a little burlier than the others. Still a superb drink and a wine with many years ahead. 95.

2017 (cork): Dark blood red. Beautifully fragrant. Florals, truffles, spices, delicatessen meats, cherries, a note of the undergrowth. Good complexity. There is vibrant acidity. Concentration, great length, a seamlessness and a sumptuousness to it.

Excellent structure, soft cushiony tannins. A wine with 15 years plus ahead of it. Expect this score to rise in coming years. 96.

2018 (screwcap): An absolutely cracking wine. One report suggested that there was 0.4 percent Viognier included here. Oak was just 32 percent new French. Color is dark purple/black. The aromatics are so alluring.

There is a plushness and velvet note to this wine, while it is wonderfully generous. Black cherries, leather, truffles, mulberries. This is dense but it dances. Already a creamy texture and an opulence to it. Good complexity, even at this early stage.

Excellent balance, such soft tannins. Fabulous length. Such a great future ahead of it. A star. 98.

For more information, please visit www.trinityhill.com.

You may also enjoy:

Gimblett Gravels Annual Vintage Selection From Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand: Wine Highlights And Scores

New Zealand’s Craggy Range Winery And The Revelatory Le Sol Syrah: Tasting Notes Inside

Penfolds 2016 Grange And G4: Superlative Wines, Well Deserving Of 100 Points. Each!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!