History Of Watchmaking: Günter Blümlein, A. Lange & Söhne, Jaeger-LeCoultre, IWC, And The LMH ‘Supergroup’

October 1, 2021, marks 20 years since Günter Blümlein passed away at the age of just 58. His untimely death meant that A. Lange & Söhne had lost its visionary co-founder and the watch world lost a charismatic businessman and strategist who was a crucial factor in driving the mechanical renaissance of watchmaking in the late twentieth century. His legacy was – and remains – the three so-called LMH brands, which formed the nucleus of Richemont’s high-level manufacturing capabilities at the turn of the millennium.

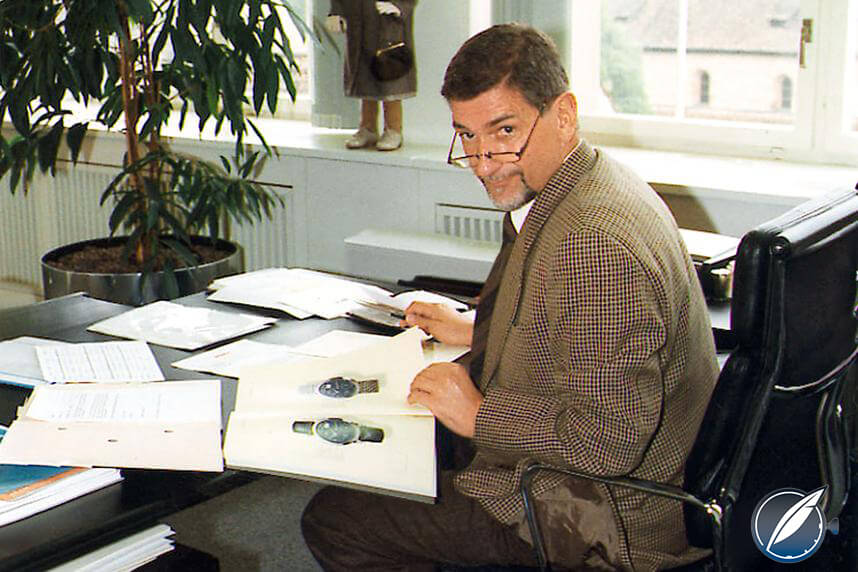

Günter Blümlein at work in the year 2000

In short, the modern successes of A. Lange & Söhne, IWC, and Jaeger-LeCoultre can be chalked up to the vision of a single man at a time when no one was thinking about the future of the mechanical watch: Günter Blümlein.

Günter Blümlein and Walter Lange at the F.A. Lange memorial in Glashütte in 1991

And if you’re not sold yet, consider this: the memoirs that Walter Lange published in 2005 called The Revival of Time were dedicated to his late wife, Jutta, and his late business partner, Günter Blümlein. (This, by the way, is a book I highly recommend!)

While this may seem out of the ordinary, it is typical of the way that people who worked with Blümlein felt about his managerial style and the work to which he passionately dedicated his life. For Walter Lange, resuscitating his family’s legacy by re-founding Lange Uhren GmbH was far more than a business prospect: it was a lifelong dream.

For the many, many skilled watchmakers in Glashütte, the rebirth of A. Lange & Söhne was, granted, a livelihood, but it also was – and remains – a national source of pride. When Lange and Blümlein reestablished Lange’s birthright in 1990, the experienced manager in his typically visionary style saw several opportunities, but he never forgot what watchmaking meant to the people involved.

Blümlein and Lange are only one part of an epic story that involves three brands, a host of gifted watchmakers, entrepreneurs with far-reaching ideas, and thousands of calibers and watches that can well be said to be among the best in the world. The story of the “LMH brands,” and thus that of their main protagonist Günter Blümlein, began in the 1970s . . .

Swiss pre-history: IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre in the 1970s

In the beginning there was the quartz crisis. According to Hannes Pantli, now member of and spokesman for IWC’s board of directors, this wasn’t all. “They say it was the quartz crisis, but it wasn’t only that. It was the termination of the Treaty of Bretton Woods [which regulates cross-border employment in Europe among other things], the exchange rate . . . and the price of gold, which was fixed the whole time at 5,800 Swiss francs per kilogram. Then it was released, allowed to free float . . . it went all the way up to 43,000 francs. Our watches became three times as expensive in dollars without us doing anything at all.”

Hannes Pantli in 2013

Pantli joined IWC in 1972 and he was instrumental in setting IWC down its modern path. “No one knew what the future would bring. Thus, we began with tuning-fork watches and then the quartz watches.” In 1978, IWC was for sale, and VDO Adolf Schindling AG – a German automotive group – answered the call on its search for suitable partners to set up a strong European watch group to counterbalance Japanese competitors.

“This was the idea of [VDO CEO] Albert Keck and his people. There were several small German brands involved, just about every French brand, and ‘on top’ one or two Swiss companies. A giant concern involved was Matra,” Pantli remembered during a chat I had with him several years ago, “and they had the order from the French government to save the French watch industry. They had had very good experience with VDO in making auto instruments.”

The Swiss Sapphire Group, which owned Jaeger-LeCoultre and Favre-Leuba, was also involved, Pantli remembered. “It ended up being like a tower of Babylon: the French could not speak German and the Germans did not speak French.” This caused Blümlein, an engineer previously instrumental at Junghans, but at the time employed by VDO, to get involved: he spoke both languages fluently and had an extensive understanding of watchmaking. The great European watch resistance never happened, but VDO acquired IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre, and the then-37-year-old Blümlein set to work making these Swiss names great once again as their CEO.

IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre: new leases on life

“Mr. Blümlein naturally saw very quickly that the biggest problem with Jaeger-LeCoultre was that the brand manufactured wonderful products but hadn’t cared for the ‘brand’ as such. They supplied movements to Cartier and Vacheron Constantin, but you can’t earn real money with movements. The first thing he had to do was build up the brand again, and that’s when its real success began,” Pantli recalled.

IWC made its comeback with the help of a collaboration with Porsche Design and Blümlein’s production reorganization. Additionally, Blümlein repositioned the ailing Schaffhausen-based company by pushing its product policy to focus on technical sophistication, with particular focus on men’s timepieces.

In IWC’s monumental book Engineering Time Since 1868, author Manfred Fritz characterized Blümlein thus: “IWC’s generally straight-thinking boss, who had once said that his favorite occupation was picking up trains that had come off the rails, putting them back, and making them run in the opposite direction . . .” This so very aptly describes how Blümlein handled IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre in their times of need.

Jérôme Lambert, now CEO of Richemont

Jérôme Lambert, CEO of Jaeger-LeCoultre from 2002 through 2013 and now CEO of Richemont, recalled to me about ten years ago specifically how Blümlein resuscitated the Le Sentier-based brand. “Firstly, he stopped supplying others and removed 45 percent of all activity at the time. He was also the one to convince VDO and Audemars Piguet [Audemars Piguet owned 10 percent of Jaeger-LeCoultre at the time] to invest additional millions to create a bridge for continuity. And then he defined the company’s theme.”

Lambert went on to liken Blümlein’s corporate melody to the leitmotif of a strong piece of classical music. “When he went through the lines and products every year, it’s what he expressed. And then the team around him and [Henry-John] Belmont were capable of understanding and enriching it [in order] to conduct the other musicians of the orchestra . . . to make a full symphony instead of only a ringtone.”

The incredible Germanness of being

Multiple times Walter Lange described his longtime business partner to me as a “full-blooded entrepreneur,” a man full of ideas, a perfectionist, and a hard worker in addition to being a “marketing genius.” From its re-founding, Lange Uhren GmbH joined its two sister companies within VDO’s LMH (Les Manufactures Horlogères) group, which Blümlein formed to provide a home for the three exceptional brands.

“The next important step came when the Berlin Wall fell,” Pantli reminisced. “Keck, Blümlein, and I were at a restaurant when we heard on the radio that the Wall had fallen. Because I had already been to see the Langes in 1976, I said, ‘This would be the moment.’ The two just looked at each other . . . in A. Lange & Söhne’s ten-year anniversary publication it was nice of Blümlein to write that I had had the idea because anyone could have had it afterwards. Two weeks later, we were in Glashütte to look around and see what could be done.”

The A. Lange & Söhne factory in Glashütte in 1994: the wild, wild East

The Berlin Wall came down on November 9, 1989, and one year later Walter Lange and Blümlein officially registered Lange Uhren GmbH on December 7, 1990. The trio of LMH brands was complete.

IWC was instrumental in getting A. Lange & Söhne up and running. Blümlein had an office each in Schaffhausen (IWC) and Le Sentier (Jaeger-LeCoultre), but after 1990 he spent much more of his time in Glashütte. “I take my hat off to IWC,” Walter Lange remembered to me about ten years ago. “They treated our people so collegially. The first technicians we hired, we sent directly to IWC for training . . . it worked out beautifully. I am so thankful for the IWC people.”

The first A. Lange & Söhne Lange 1 from 1994: not much has outwardly changed in this model in all this time

Kurt Klaus, IWC’s legendary creator of the Da Vinci perpetual calendar, personally trained Lange movement designers Annegret Fleischer and Helmut Geyer, and the three of them got the movement for the Lange 1 up and running.

Lambert was Jaeger-LeCoultre’s young financial controller at the time. “IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre grew and exchanged and came together [in the Blümlein era],” he fondly remembered. “None of the Lange team came from Jaeger-LeCoultre or IWC. The Germans, having saved a big part of their knowhow and technical background, had a very strong culture of fine watchmaking different from the Swiss. It was a very fertile kind of structure, and I would say that the vision of Mr. Blümlein could flourish within it. IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre were perhaps in charge of bringing some water, but the ground, the plants, and the mix between Mr. Blümlein and Glashütte made it. Truly, we just added some water: their strength, their culture, their vision, and their aesthetics is all them.”

October 24, 1994: (l-r) Günter Blümlein, Walter Lange, and Hartmut Knothe between posters of the first four models launched by A. Lange & Söhne

The introduction of the four A. Lange & Söhne wristwatches in 1994 marked the rebirth of Germany’s most renowned historical watch brand and the culmination of a dream for both Blümlein and Walter Lange.

Takeovers

In February 1999, Vodafone took over Mannesmann. Vodafone’s core business was mobile communications, and it wanted to divest itself of all investments that were not affiliated. Thus, the LMH brands were put up for sale, and a fairly public bidding war between Richemont, Swatch Group, and LVMH ensued.

The victor ended up being Richemont, the Swiss luxury group owned by South African Johan Rupert that already owned the so-called Cartier group, which also included Piaget and Baume and Mercier. “Rupert paid the most, a crazy price of 3.04 billion for the group,” Pantli recalled. “This was totally crazy, something like seven times the turnover – not profit! It’s now clear that this was an absolutely wonderful investment.”

Other reputable brands such as Roger Dubuis, Officine Panerai, and Vacheron Constantin soon followed, making Richemont one of the most powerful groups in the luxury watchmaking sector. In the year 2000, the acquisition of the LMH brands ensured powerful movement technology for the group, and Blümlein remained in charge of all three of them.

Shortly after beginning as chairman and delegate of the advisory board of the three “LMH brands” at Richemont headquarters in Geneva, which led to the position of executive director, Blümlein passed away after a sudden and short illness at the age of 58.

Walter Lange dearly missed his business partner, and Lambert, who began working with Blümlein when he was 56 (Lambert then being the tender age of 27), said that Blümlein possessed some extraordinary managerial qualities that can be broadly termed as visionary.

“That’s what everybody will say,” Lambert confirmed to me a decade ago. “He defined what Jaeger-LeCoultre had to be, what IWC had to be, what Lange had to be. Lange is where he wanted Lange to be in the year 2000, no question about it. Today, when you speak to people of the group’s upper managerial segment, you only hear respect about what he did and the frustration of what he could have even now been doing for the other [brands]. We have the privilege to have been doing 20 years of that.”

The passing of Günter Blümlein

In his memoirs, Walter Lange wrote that A. Lange & Söhne’s rebirth was only possible thanks to an “exceptionally productive cooperation with IWC and the doubtlessly congenial partnership” with Blümlein.

Born in 1943, Blümlein’s childhood and youth were dominated by Germany’s Wirtschaftswunder, the “economic miracle.” Following Germany’s destruction in World War II, Blümlein’s hometown of Nuremberg experienced a sharp upturn when well-known industrial firms settled there during the Wirtschaftswunder period, which may have contributed to Blümlein’s decision to study engineering. His career took him to the Black Forest to work for the Diehl Group, which had taken over Junghans in the 1950s, starting him down his path toward the world of watchmaking, a place he was obviously destined to be.

Blümlein’s sudden passing on October 1, 2001 was a hard blow to the close partners he had surrounded himself with. In fact, Lange recalled this as being one of the “worst experiences” of his life. Blümlein, a life-size bust of whom hangs in the main entrance of Lange Uhren GmbH in Glashütte, continues to vividly live on in the output and employee memories of his three “babies.”

Günter Blümlein’s own A. Lange & Söhne Pour le Mérite Tourbillon, number one of the 50 platinum pieces

The closing paragraph of Martin Huber’s epilogue in Walter Lange’s memoirs reads, “One of the greatest human experiences for me remains the relationship between Walter Lange and Günter Blümlein, who died much too early at the height of his career in October of 2001. That was a relationship free of any type of vanity and rivalry whatsoever, and each of the two partners was able to concentrate all of their energies and powers on the tasks that lay ahead of them. The rebirth of A. Lange & Söhne is for me the success story of two people in whom idealism and competence were found and joined in a very rare manner.”

Pantli also related human kindnesses found in the uncompromising manager that are more than unexpected.

“At Lange, every inch is Blümlein,” Lambert recalled. “Every single attitude is Blümlein-made. You just have to have enough humility to understand and feel it and reconsider what you think to be in line with what he was expecting from the brand. He was projecting what Lange had to be and should be, and even what Lange would have been if nothing had stopped it for 40 years. Somehow, it was kind of his projection into time.”

“He was a universal genius,” Walter Lange once told me with a serious look in his eye. “There have been two luminous experts in the Swiss watchmaking industry [of the modern age]: one was [Nicolas G.] Hayek and the other was Blümlein.”

You may also enjoy:

The Life And Times Of A. Lange & Söhne Re-Founder Walter Lange

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Bravo! Outstanding article.

In either 1999 or 2000 I was at a dinner with Herr Blümlein, and several attendees asked him he did bid for A. Lange & Söhne. He shrugged his shoulders and simply said “I can’t afford it”. What a shame —that’s what banks and private equity and investor syndications are for.

I’m not sure what Herr Blümlein would think of his LMH brands and their products today.

Yes, that would be interesting to know, Michael. Unfortunately we never will.

It’s hard to believe that Lange and Söhne watches haven’t been evolving continuously for 200 years like their peers.

I think you mean Bretton Woods rather than Brighton and Wood (which sounds like a pair of English cricketers)

Ah, yes, thank you for the correction there, Colin. I have corrected it.

Donnerkiesel”, this is a powerful story. It hits me like a thunderstorm. What a pleasure to read. It illustrates the life of G. Blümlein as an important contribution to a part of the economic history in united Germany.

What an exceptional entrepreneur. The quotes and citations really draw me in. The life of a true visionary character making use of a historical window of opportunity. Thanks alot for this great reminder Elizabeth.

Thanks for reading, Thomas!