The Joy Of Champagne: Tasting Through Different Styles From Dom Pérignon And Others At A Champagne Extravaganza Lunch

by Ken Gargett

One of the things I most enjoy seeing at champagne tastings and classes is the dawning on faces as those present realize that not all champagne is the same. This might be obvious to seasoned wine lovers, but you would be amazed at how often beginners, or those finally getting serious about champagne, don’t realize how varied the champagnes from different houses and of different styles can be. They really are!

Of course, it is necessary to taste through as many as one can to come to this realization. Then I could point out that it would surely be impossible to mistake an elegant Taittinger NV for a rich vintage Bollinger (except that I have done exactly that, and in a competition no less – needless to say, I did not win that year). Each house has its own “DNA” and there are a wide variety of different styles. They are all very much worth exploring.

A pyramid of rosé champagne

We have the basic non-vintage (multi-vintage) champagnes that are crucial to almost every house. Vintage champagnes speak for themselves.

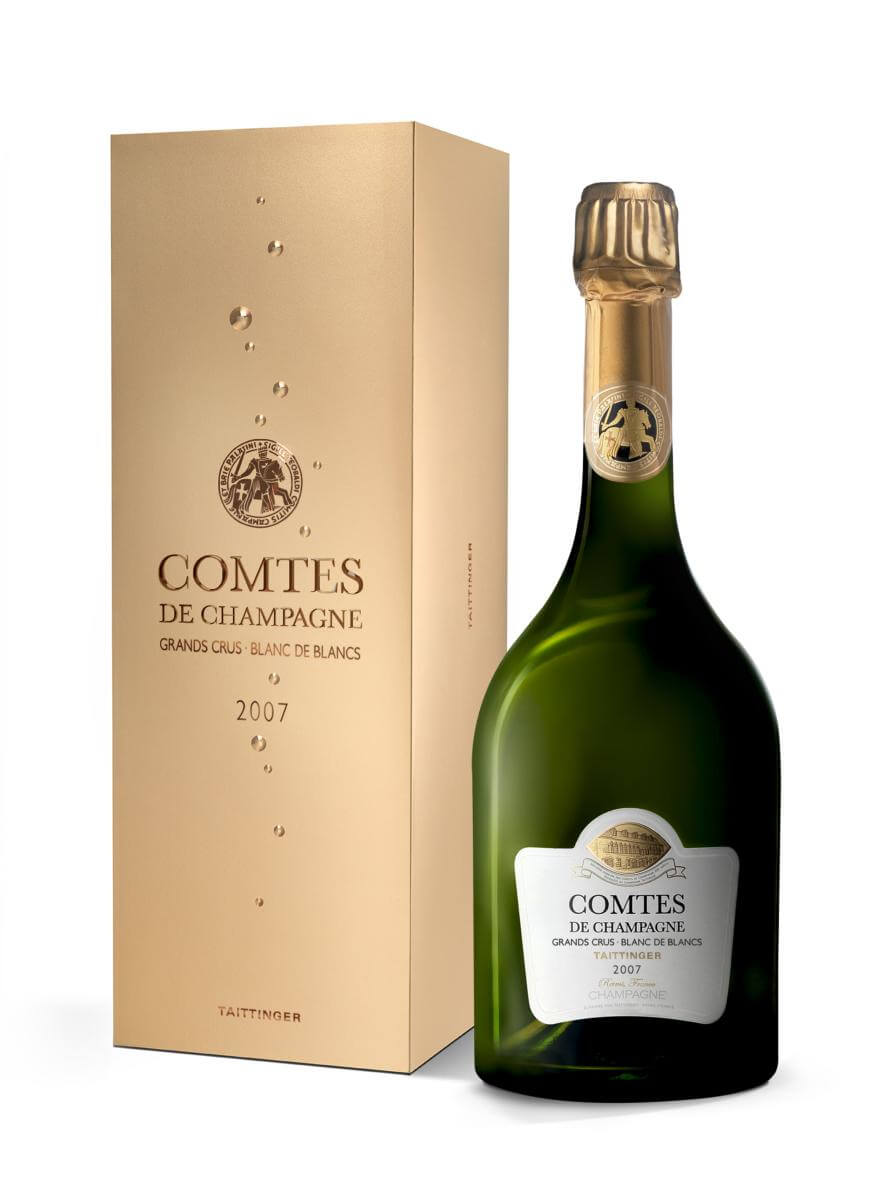

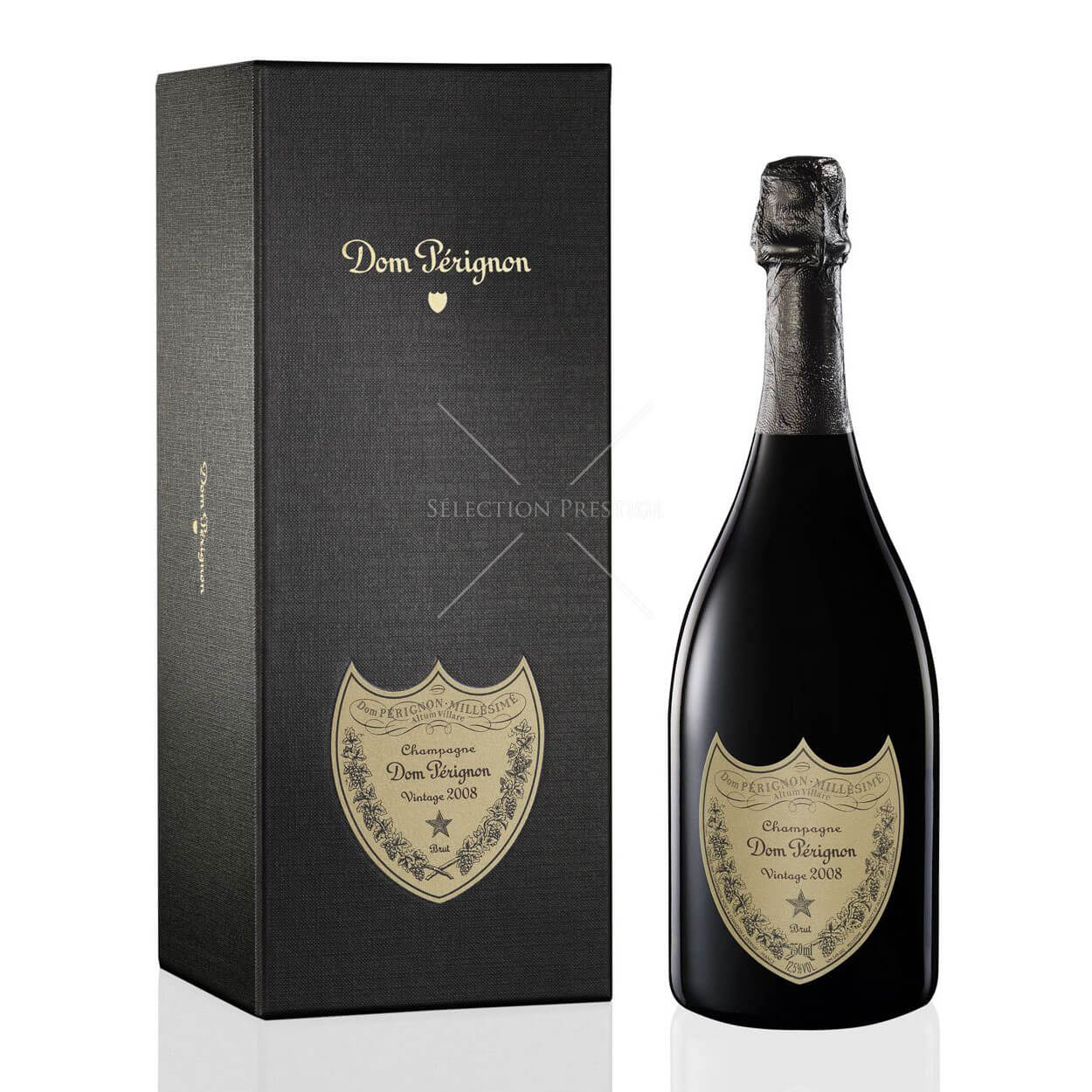

We have rosés, both vintage and non-vintage; blanc de blancs, again both vintage and non-vintage (champagnes made from 100 percent white grapes, almost inevitably Chardonnay); blanc de noirs, yet again vintage and non-vintage (champagnes made from black grapes, inevitably Pinot Noir, Meunier, or a blend of the two); and prestige cuvees, which could be any of the styles – like Taittinger’s Comte de Champagne, which is a stunning blanc de blancs; Dom Pérignon, a blend; or Bollinger’s incredibly rare Vieilles Vignes Françaises, a blanc de noirs.

Champagne Taittinger Comtes de Champagne Blanc de Blancs 2007

There are completely dry styles with no dosage at all; sweeter champagnes (once far more fashionable than they are today); the Vinothèque styles, where the champagne will have spent extra time in the cellars on their lees before disgorging; and older champagnes, which were disgorged normally but have spent that extra time in the cellar on cork. I’m fairly sure I must have missed one or two.

Never was all this more apparent to me than very recently when we had Didier Mariotti, chef de cave at Veuve Clicquot, in town (and, yes, I will definitely be looking at Veuve Clicquot, very soon). Mariotti is an old friend of a number of locals from his time with Mumm and after his Veuve Clicquot duties were complete a few of us managed to get together thanks to the incredible generosity of some friends to enjoy a quiet champagne lunch . . . which turned into one of the most extraordinary champagne extravaganzas I’ve ever encountered. During that occasion, I took a little time to reflect on just how different champagnes can be while still being of superlative quality, and I simply could not let the concept go without some coverage.

A superlative champagne lunch

We started the day with a couple of champagnes to warm up: the Delamotte Blanc de Blancs 2007 and the Deutz Blanc de Blancs 2009. It would be fair to surmise that what we have here would not be that different, but they already allow us to see just how varied champagnes can be.

Delamotte is a famous old house based in the heart of the great Chardonnay vineyards in Champagne, the Côte des Blancs. Delamotte often benefits from the fruit Salon does not use if that house does not release a vintage, but in 2007 both houses made scintillating champagnes. Delamotte offers finesse and delicacy while Deutz is also usually on the more on the elegant side, though perhaps a little richer than Delamotte. There is more of a divergence here when we get to the vintages.

The 2007 vintage is an under-the-radar year, not widely declared, but those basing their wines on Chardonnay have made some crackers; think Taittinger’s Comte de Champagne and Salon. There is a focus and finesse to these wines. Two thousand nine is very different. Considered a good vintage and much more widely declared, this is a ripe, full, and generous year resulting in bigger, bolder, fuller wines.

Pierre Peters Blanc de Blancs Les Chétillons 2006

Then we got serious with the Pierre Peters Heritage. I am a big fan of the Pierre Peters Les Chétillons, a stunning blanc de blancs, but this was a something else. I had heard of this wine, but it never occurred to me I would ever get to try it. This incredibly rare champagne is yet another variation on the theme with a mindboggling array of reserve wines. Reserve wines used in multi-vintage blends rarely go back more than a decade or two at most. The Heritage is comprised to one-third of the 2010 Les Chétillons as the base wine with the remaining contribution from vintages back to 1921: 1921, 1947, 1959, 1964, 1966, 1969, 1973, 1976, 1979, 1982, 1985, 1988, 1990, 1996, 2002, 2004, and 2006 to be specific (this is largely a roll call of the great years of the region). Then eight years on lees.

The result is an incredibly complex wine, and yet one still fresh, vibrant, and dancing. Layered, intense and exquisite, we have notes of stone fruits, lemons, florals, glacé fruits, toast, and a whiff of beeswax. Seamless and perfectly balanced. Astonishing stuff. 99 (to be honest, it probably deserved the perfect score, but I was a bit worried that with more to come I’d paint myself into the proverbial corner).

Comparing the 1993 Dom Pérignon to itself

The Pierre Peters Heritage alone would have done me for the day, but we were only just beginning. It was Dom time and a fascinating exercise. We compared the 1993 Dom Pérignon with itself. Allow me to explain.

Dom Pérignon

The 1993 Dom Pérignon initial release, which had been stored in our hosts’ perfect cellar, was served alongside the 1993 Dom Perignon Oenothèque. The Oenothèque program, now the Plenitude program where the wines are either P2 or P3 depending on length of time on lees (and, yes, much more, but that requires a separate piece), is where the wines are held in the maker’s cellars for an extended period on lees before disgorging. In this case, the Oenothèque was disgorged in 2005, so it had also enjoyed a significant period of cork aging.

The 1993 vintage has always been considered a fairly average vintage but on the evidence here perhaps a re-examination might be in order.

The initial release was a deep golden color. It was complex and intense, utterly glorious with such length. Notes of quince, hazelnuts, cumquats, orange rind, and even the merest hint of vegemite. Concentration and focus. Interestingly, Charles Curtis MW, in his Vintage Champagne, definitely not a fan of this year, notes that the Dom was already tired after ten years (2003). This bottle could not have been more different.

The Oenothèque opened so wonderfully fresh. A much lighter lemon color, there was a brightness and vibrancy here. A laser-like focus with great persistence and length. Notes of jasmine and lemon zest.

At first, I had the pair on level-pegging but with time the initial release showed more and more and blew us away. I had it at 98 and the Oenothèque at 96.

When too much Dom is never enough! Next cab off the rank was a magnum of the 1978 Dom Pérignon disgorged in 1998 (serving champagne from magnum, the perfect size, is yet another variation on the theme). Champagne vintages are always up for debate. Curtis gives 1978 a single star. It was never thought of as a great year, but that seems harsh. He gives 1979 the full five stars, which seems very generous to me. He has it topping both ’75 and ’76. For me, 1975 is the pick of the lot. No matter. Here was a wine that had developed maturity and complexity with great length. Glorious stuff and certainly drinking way above what the vintage should be offering by any standards. 97.

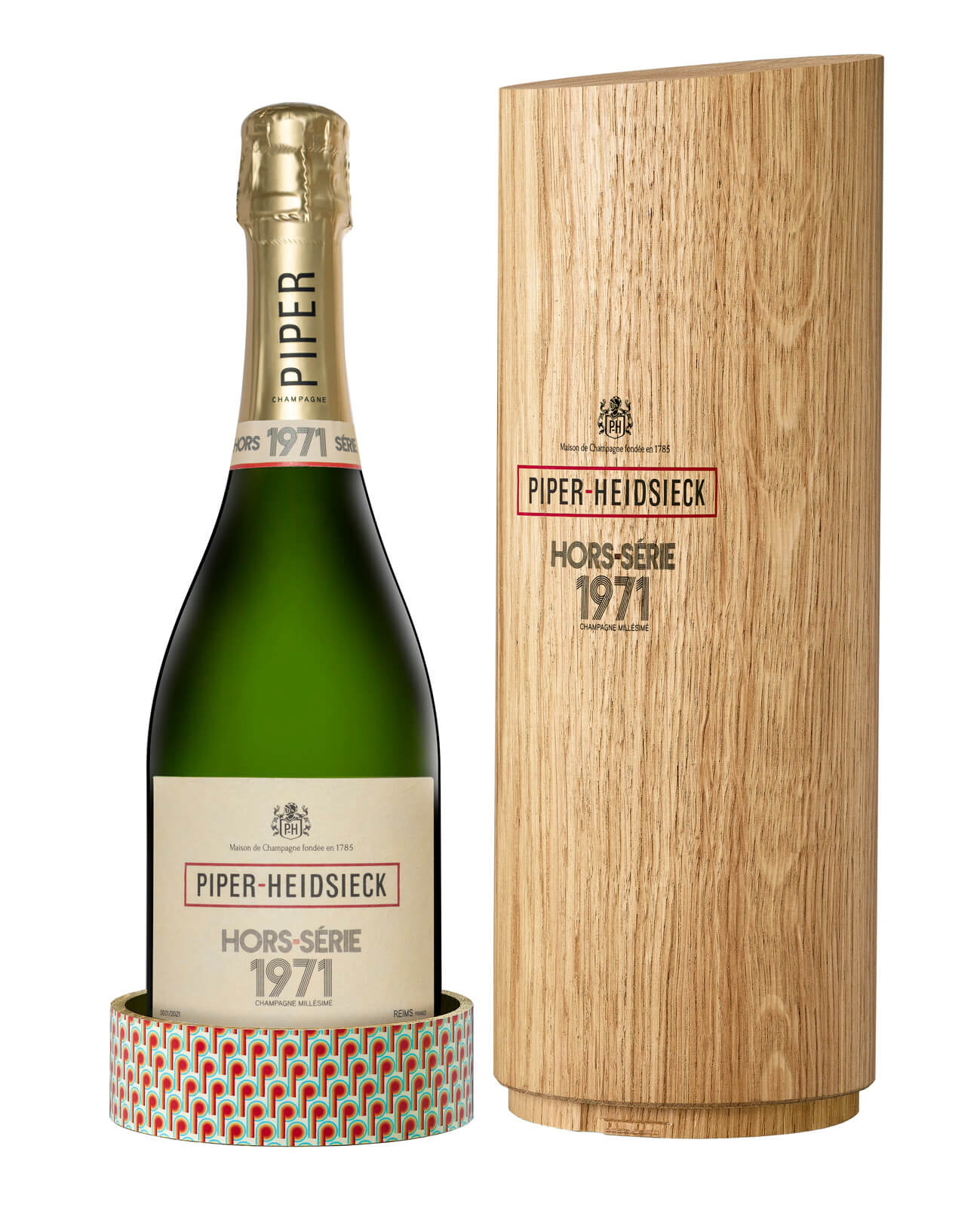

1971 Piper-Heidsieck Hors-Serie reappears

Still in the 1970s, we then moved to an old friend I had written about around a year ago, the 1971 Piper-Heidsieck Hors-Serie, disgorged after an almost unheard-of 48 years on lees. A wonderful surprise and a great pleasure to see it again. While there are legal minimums for these things, the usual period on lees for the better non-vintages is around two to four years; for vintages, four to eight; and for prestige cuvees, six to 12 years. Forty-eight is ridiculous, but it gives characters that are unprecedented elsewhere.

Piper-Heidsieck Hors-Série 1971

Some may recall from my article on this champagne that in a zoom presentation (thanks, Covid) chef de cave Émilien Boutillat discussed how the small production had headed off in several different directions. As I mentioned then, “You won’t quite know until you open it, but fear not: I have no doubt you’ll love what you discover.” For example, one direction was to venture into that wonderful old truffles and mushroom character. Another was a citrusy style. While yet another is exhibiting “dry vegetal and dried flower notes.”

Mine at that time? “A wonderfully enticing golden color. The nose was immediately gloriously complex with coffee bean notes. The wine is both fresh as the proverbial daisy and showing serious development. Great intensity with notes of spices, nougat, stone fruit, dried figs, and fresh ginger. Excellent focus and great length. It did not take long but all of these different characters soon gave way to what proved the most dominant of all: a magnificent aroma/flavor most reminiscent of a freshly baked apple pie or a dish of rich, cinnamonny, stewed apples. Gorgeous. This character never left, and even when I finished the bottle the next day it was still to the fore! That baked apple character was another of the threads that Boutillat has seen in the wines; he talks of ‘balance and harmony’ and he is spot on.”

So what would we encounter this time? None of that baked apple character at all but the dry vegetal and dried floral notes were immediately apparent. Fascinating how the same wine can head off to provide a variety of different experiences. Still complex and with excellent length, it was a wonderful champagne and I gave it 97, though I probably preferred the earlier baked apple style. It is, of course, purely personal at this level.

We were not finished yet. A champagne that is almost a unicorn, so rare it is: the Bollinger Vieilles Vignes Françaises, this one from 1992. It has been many years since I last saw any vintage of this wine – on a visit to the house as it happens. It is a blanc de noirs, 100 percent Pinot Noir, and widely considered the greatest version of that style in the world (Krug may wish to dispute that with its Clos des Ambonnay).

Bollinger Vieilles Vignes Françaises 1992

It is made from two tiny patches of ungrafted vines in Aÿ. Curtis only gives the vintage two stars, but he talks very favorably about it. I suspect that many houses did not declare 1992 as we had just seen the amazing trio of 1988, 1989, and 1990, so the houses were not short of vintage releases. Richard Juhlin is a fan of this wine, giving it 97, which was the same for me. Rich and complex, it has fabulous depth and length. What a privilege.

Back to Dom Pérignon’s magnificent rosé from one of the greatest vintages of all time, 1988. Such power, such concentration. There are florals, red berries, and freshness, even after all this time. Richness, depth, and persistence. A truly great rosé. 98.

The day would not have been complete without a Krug, and this one from that brilliant year, 1988. Extraordinary. There were notes of lemon custard and orange rinds. Cassis and blueberries. Spices, notably cardamon. Great acidity and knife-edge balance. Completely different in style, of course, to the rosé but equally special. Still with many years ahead of it. 99-100.

With Didier Mariotti in attendance, a Veuve Clicquot was essential. Our hosts thought a bottle of 1964 might suffice. Nineteen sixty-four is perhaps the vintage most likely to challenge 1988 for greatness, but at almost 60 years of age who knew how it would show. Incredibly well, as it happens. A deep bronze color with mature notes, cassis, spices, and leather. It confirms that well cellared champagne can age brilliantly for many, many years. 95.

Finally, one of the truly great champagnes to conclude, the 1996 Salon, a famous blanc de blancs. Still so fresh and young, this will outlive most of us. My notes were simple: “Lord, take me now. 100.”

Okay, not terribly helpful technically, but you get the gist. Not sure champagne gets better, but obviously it does get different. As an aside, a week later, I had the chance to enjoy a 1990 Salon. Another great vintage and great champagne, but much more advanced and mature. Great stuff, but I’d be drinking it sooner than later. The 1996? Any time you like.

I have not touched on how well these champagnes went with a wide array of dishes but that might be better left to another time.

This might seem like an exercise in utter hedonism (and it pretty much was thanks so much to our most generous hosts), but as an exercise in showing how versatile and how incredibly varied champagnes can be, it was a masterclass.

You may also enjoy:

Dom Pérignon 2008: From The Monk’s Earliest Beginnings To The Most Glorious Champagne Vintage

Salon Le Mesnil Blanc De Blancs: An Original ‘Unicorn’ Champagne

Piper-Heidsieck Launches Hors-Série 1971 Champagne: An Incredible 48 Years On Lees!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!