False Scarcity and Steel Sports Watches: A Collector’s View

by GaryG

“Ferrari will always deliver one car less than the market demand” – Enzo Ferrari

One of the pleasures – if one can call it that – of collecting is that you can’t have everything you want! For almost everyone, there’s the little problem of resources and affordability; I’ve written previously about that constraint and how throughout my collecting journey I have needed to “sell to buy.”

In other instances, though, the frustration comes from the limited number of pieces available of a given reference or from a particular brand. In the vintage world, some coveted pieces were made in very small quantities and aren’t being made anymore, making them nearly impossible to acquire – especially if you’re looking for an example in especially good condition.

Unobtanium, at least at retail price (and now discontinued): the author’s Rolex GMT-Master II

But the “unobtanium” phenomenon isn’t limited to watches from the past: in the broad and deep landscape of contemporary watch production, there are a variety of references for which supply seems to lag demand by much more than Enzo Ferrari’s legendary “one less.” Nowhere is this more apparent than in the current market for select steel sport watches, and that imbalance has resulted in some interesting dynamics – not to mention loud choruses of complaints from prospective buyers.

A brief, incomplete, and somewhat personal history of managed scarcity in luxury goods

For a broad overview of the phenomenon of scarcity in luxury goods, I’d recommend Lucy Alexander’s article on the Robb Report site: From A Rolex To A Birkin, Why Some Luxury Items Are So Hard To Get.

I won’t repeat her arguments (or outline a few quibbles I have with her reasoning) here, but I will dwell for a moment on the case of that classic exemplar of the art, Enzo Ferrari.

Ferrari was first and foremost a racer, and famously disliked producing road cars; as a result, he had little desire to expand road car production beyond the point needed to fund his racing operation. At the same time, he was a shrewd businessperson with a keen sense of revenue and profit maximization and knew that the shortest path to raising the needed cash was to sell fewer cars at higher prices.

By remaining true to this principle through periods of higher and lower demand, Ferrari was also able to sustain the residual value of cars already made and support his brand’s new-car pricing over the longer term – a topic I’ll return to shortly when I talk about the current watch world.

Of course, no policy is so perfect that it operates optimally under all conditions or can’t be perverted in some way. I came out on the good side of the imperfections in 1993 when, after several years of booming Ferrari market prices following Enzo’s death, customers figured out that perhaps Ferrari would be making good cars for a while yet and demand softened. When I bought my beloved 512TR, I received not only a discount but a fully paid trip to Italy for the Pilota Ferrari driving school as incentives.

Hard to get: the author drifting his Ferrari 599 GTB at Laguna Seca

The flip (literally) side caught me out in the 2000s, though, when booming demand for Ferraris led to the emergence of a class of Ferrari buyers who bought cars at the right moment, flipped them at above retail, and returned to the dealer to do it again – and again.

Somehow these folks became classified by Ferrari dealers as preferred customers, and I found that I couldn’t even get on a waiting list for a new car – until I succumbed to the unsavory practice of tying, in which I agreed to buy a less-desirable used four-seat model at its asking price in exchange for a spot in the new-car queue.

In a classic display of GaryG market timing (remember, folks, I’m an enthusiast collector, not an investment advisor), in March of 2008, just before the bottom fell out of the economy, my name magically rocketed to the top of the waiting list. I passed on my slot and bought a year-old, lightly driven car at a substantial discount, selling the four-seat car at a considerable loss as well.

While it’s somewhat cathartic to tell my story, the main reason I’ve set it out here is to illustrate a migration of the role of managed scarcity in luxury goods: from a method to sustain overall pricing for a brand to a tactic to force the purchase of less desirable items in exchange for access to more coveted ones. Whether it’s a Birkin bag or a Rolex GMT, the ability to buy “hot” items seems more and more to depend on other purchases made from the brand or retailer.

Turning to the world of watches

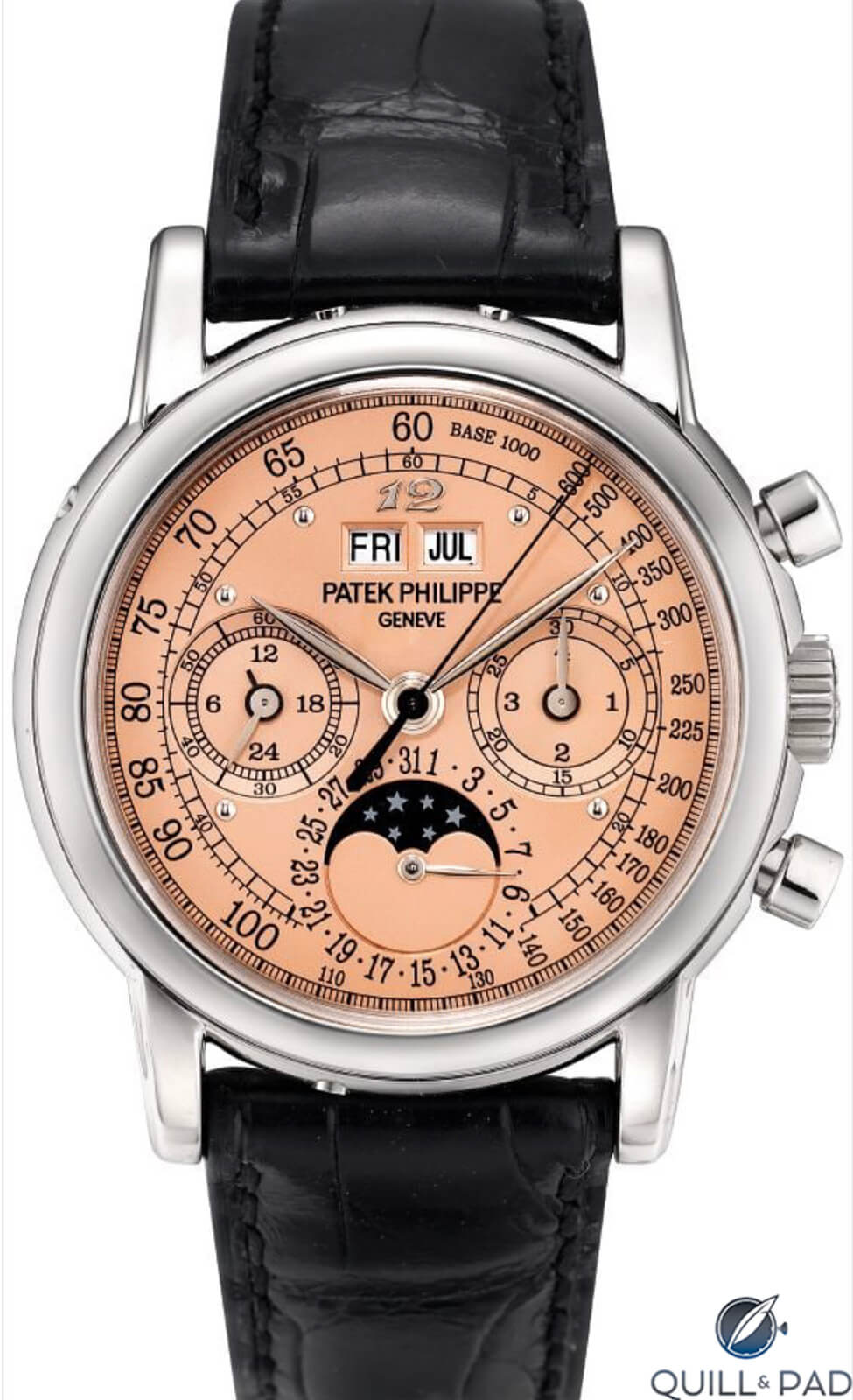

While all , or at least many, of the facts are to some extent shrouded in the mists of history, it was most likely Patek Philippe that first mastered the use of what I’ll call the “Ferrari” model in the world of high-end horology. Access to the brand’s highest complications was reserved for the loyal customers of the brand and by application only, and top customers (with Eric Clapton and Michael Ovitz as prominent examples) were sometimes granted the privilege of requesting unique pieces.

Patek Philippe Ref. 3970 commissioned by Sir Eric Clapton (image courtesy Phillips)

I recall well the experience of sitting several years ago with a collector friend at the Patek Philippe Geneva Salon, where he had not previously done business, as he asked about the availability of a certain perpetual calendar chronograph.

The sales advisor asked my pal to write down on a note pad a list of the Patek Philippe references he owned; when my friend flipped the sheet over to continue on the other side, he was informed that it might well be possible to find a piece for him. Notably, there was no hint of, “If you want x now, it would be very helpful if you took y off our hands.” Rather just a validation of past buying behavior.

While it was easy for me to resent that I wouldn’t have had the same access, by the same token I understood that when a manufacturer has a finite capacity to create its finest pieces, it might well want to ensure that the majority of them go to the most loyal buyers.

Finally got one, though: the author’s Patek Philippe Ref. 5370P

More recently, though, it’s not so much the ultra-complicated platinum and gold pieces that are objects of desire and in short supply: it’s the more prosaic sport models, especially those in steel.

Once upon a time (actually, not that long ago), it was possible to go into an authorized Rolex dealer and buy a GMT-Master II “Batman” off the shelf at its suggested retail price. I did just that in late 2015, just before Rolex steel sports watches became the subjects of a buying mania.

Somewhat more recently, a good friend purchased, at suggested retail, a white-dialed “piano key” Patek Philippe Reference 5711A Nautilus that was in stock at the brand’s Geneva Salon. And although it’s been a while, you could also once buy an Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Reference 15202 in steel with blue dial without standing on your head or coughing up exorbitant amounts of cash.

In theory, at least, manufacturers should have few problems shifting production to these simpler items; so, what’s behind the current scarcity and what should manufacturers, buyers, and retailers do?

Triumph of groupthink

With all of the great watches and diverse brands out there, is there any reason why all of us “must have” examples of only a few of them? In reality, no – even with a general shift in lifestyles leading to increased demand for more casual and sporty watches, there are many fine pieces out there that aren’t labeled Nautilus, Royal Oak, or Daytona.

And yet, with the constant reinforcement of a seemingly endless stream of daily Instagram posts, blog articles, and dealer messages, owning one of a small number of possible watches has become a badge of honor for many.

He has one, I don’t: a friend’s Patek Philippe Ref. 5711A

Brands have contributed to the mentality of scarcity over the years by introducing steady streams of limited edition pieces; and while brands such as Omega, Panerai, and Hublot receive their fair share of criticism for breathlessly hyping the latest substantially-sized “limited” runs of modestly tweaked pre-existing models, those watches do sell, at least well enough for their makers to continue repeating the practice.

It’s become a FOMO world out there; online retailer Hodinkee took things to another level with limited online batch offerings of customized watches that sold out within minutes, and even small brands like Hajime Asaoka’s Kurono have benefited from this practice, most recently with an offering of 136 examples of its Chronograph 1 selling out within ten minutes of opening the order book.

Kurono Chronograph 1 designed by Hajime Asaoka (image courtesy Kurono Tokyo)

More of us, it seems, want the same things, and those nasty manufacturers aren’t giving them to us – right?

Looking at it from the producers’ point of view

Imagine you’re the head of product policy at one of the big makers I’ve mentioned above, and you are more than well aware that demand for your steel sports line is substantially in excess of what you’re making. Why not simply make more or balance supply and demand by raising prices on the popular pieces?

Just make more? Royal Oak Ref. 15202 from Audemars Piguet

For better or worse, it’s not that simple. As a brand chief, you have to balance several considerations:

- Brand equity: ensuring that your offerings are seen as providing value for money and managing a steady value trajectory not just in response to today’s demands, but for the long term.

- Customer equity: maximizing the value of your customer relationships and balancing what you do to ensure that you have a healthy mix of new-customer acquisition and existing customer retention.

- Pricing structure: maintaining an appropriate relationship between the prices of different types of products in your overall line and signaling the inherent value of workmanship, technological complexity, and material costs in each part of your offering.

- Product policy: maintaining a diverse and healthy product portfolio that doesn’t become overly dependent on a single sub-line (witness Royal Oak at Audemars Piguet) or type of watch.

- Infrastructure costs: avoiding substantial investments in manufacturing equipment and capabilities that may fall idle when tastes shift again.

Flooding the market with today’s hot sports watches poses real risks from a longer-term perspective on most of these dimensions, and pumping up the price point would risk disrupting the brand’s full-line pricing policy in ways that would be very difficult to retract later.

Perhaps the toughest challenge is with customer equity: if your brand’s most-desired watches are among your most affordable and yet are reserved for existing customers, what will replace them as “entry-level” pieces to draw new buyers to your brand?

Tough ticket: Odysseus in steel from A. Lange & Söhne

And in some cases there are actual physical constraints: I’m sure that A. Lange & Söhne, for instance, would love to be making more steel Odysseus pieces right now than it is, but with a production capacity on the order of 5,000 or pieces per year in total and a pandemic going on, the ability to deliver even the *hundreds of steel Odysseus examples targeted for year one must be in jeopardy.

What to do?

There are no perfect solutions to the current situation, and I’m certainly not going to go on the record encouraging watch brands to invest in a bunch of tooling and parts production for products that may or may not remain at recent levels of demand.

In fact, I’m a qualified “yes” on managed scarcity – the establishment of certain luxury items and items within a brand’s line as aspirational purchases that represent the apex of a relationship with the brand over time (and that help to generate the profits needed to sustain the brand, as well as provide a halo effect to brand equity).

I’m much less a fan, however, of the way that false scarcity is used, particularly in retail channels, to coerce the purchase of less desirable items in order to obtain access to more desirable ones. To me, there’s a big difference between rewarding loyal customers and forcing a quid pro quo on buyers, whether established or new.

A few thoughts for the various participants in this dance:

For manufacturers:

- Strive for transparency. I think that Patek Philippe president Thierry Stern has done a pretty good job here, explaining that he does not plan to increase Nautilus production.

- Discourage flipping. That’s tougher, but if flippers understand that they will likely lose access to desirable items, more pieces will be left for those who will keep and treasure them.

- Discourage retail tying. I was troubled to hear that in at least one region, A. Lange & Söhne dealers are requiring the purchase of other Lange watches to get on the list for the Odysseus, and I sincerely hope that this practice, and similar practices by others, will be eliminated.

- Focus on customer acquisition. Again, not easy when your “entry” items become hot; these days, even the “entry Nautilus” Aquanauts seem impossible to find. But keep trying – without appealing and affordable entry pieces, brand longevity is at risk.

For retailers:

- Stop the obvious games. We know that in some cases you have those pieces in the back room, and in others you are holding onto your preciously small allocations to sell each as parts of multi-watch deals. Yes, you have to make a buck, but the cynicism you create is poison for the long term.

Going beyond the obvious suspects: the author’s Vacheron Constantin Overseas

For consumers, one of three things:

- Buy something else! The world is full of wonderful watches, and when I wear my Vacheron Constantin Overseas or A. Lange & Söhne Odysseus, or for that matter my Ming 17.06 or Hajime Asaoka Tsunami, I bet I feel just as good as the folks who love their Royal Oaks and Aquanauts.

- What goes up usually comes down, and we are already seeing a softening of the price bubble on some of the “must-have” steel sports pieces.

- If you absolutely, positively can’t live without one of the popular sports models, pay the going price! Markets are made of willing buyers and sellers, and if you’re one of those on the buyer side you absolutely have my blessing. Only thing: once you buy, I don’t want to hear any bitching about what you had to pay.

I’m eager to hear your views in the comments section below – in the meantime, happy hunting and enjoyable wearing!

* This article was first published on May 23, 2020 at False Scarcity And Steel Sports Watches: A Collector’s View.

You may also enjoy:

Stainless Steel Patek Philippe Nautilus Market Madness: Thoughts On The Current Market Situation

Why The Patek Philippe Nautilus Is King: A Collector Weighs In

All 7 Of The Latest Rolex Models Of 2019, Plus Some Cool Variations (Rolex Photofest!)

Great Rolex Experiment With The GMT-Master II Or How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Crown

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!