Copernicus, Alignment Shift, And The Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon: A Nerd Story

The year: approximately 400 BCE. The location: ancient Greece. A philosopher by the name Philolaus describes a system of the universe where everything revolves around the hypothetical Central Fire, the first time someone openly suggests that the earth is not the center of the universe.

Aristotle and Plato disagreed with Philolaus, so his ideas found little favor.

Jump ahead more than one hundred years and we learn of another Greek thinker, this time an astronomer and mathematician by the name of Aristarchus.

Hailing from Samos, Aristarchus found truth in Philolaus’ work and was inspired to hypothesize the first heliocentric model of the universe, replacing the Central Fire with the sun and subsequently arranging the known planets in correct order of distance from it.

Aristarchus also made the first mention that the stars, or the eighth sphere in the Platonic or Ptolemaic model of the universe, were actually much, much farther away than was believed at the time.

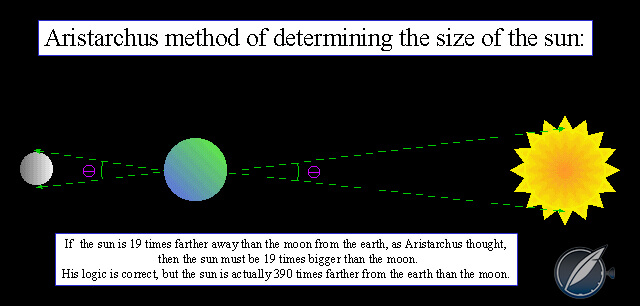

Method Aristarchus used to calculate the size of the sun; his theory was correct, but Aristarchus greatly underestimated the earth’s distance from the sun

Stellar parallax

He crudely described stellar parallax and thus the reason that the stars must be much farther away as the outcome of such a phenomenon. Aristarchus’ ideas, while accurate, were unfortunately improvable at the time ― meaning that the geocentric model prevailed for many more centuries until a mathematician and astronomer from the kingdom of Poland came along and shook up the scientific world for good. The year: 1543 CE.

At the urging of a pupil, Nicolaus Copernicus, published De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), which outlined the theory he had been discussing and detailing for decades. It described a heliocentric model of the universe that solved many of the “issues” with earlier models including the ever popular Ptolemaic universe.

One of the main issues was that of the apparent occasional retrograde motion of the planets, which was easily reconciled once the earth was allowed to move in relation to the other orbiting planets.

The solution was parallax, or the apparent shifting of alignment based on a viewer’s perspective. As the earth moves along its orbit and passes planets moving more slowly, such as Mars, they appear to reverse direction and move backward relative to the distant stars for a period of time.

The reason is that the angles created by viewing the planet against a background object differ depending on your position relative to the two separate objects.

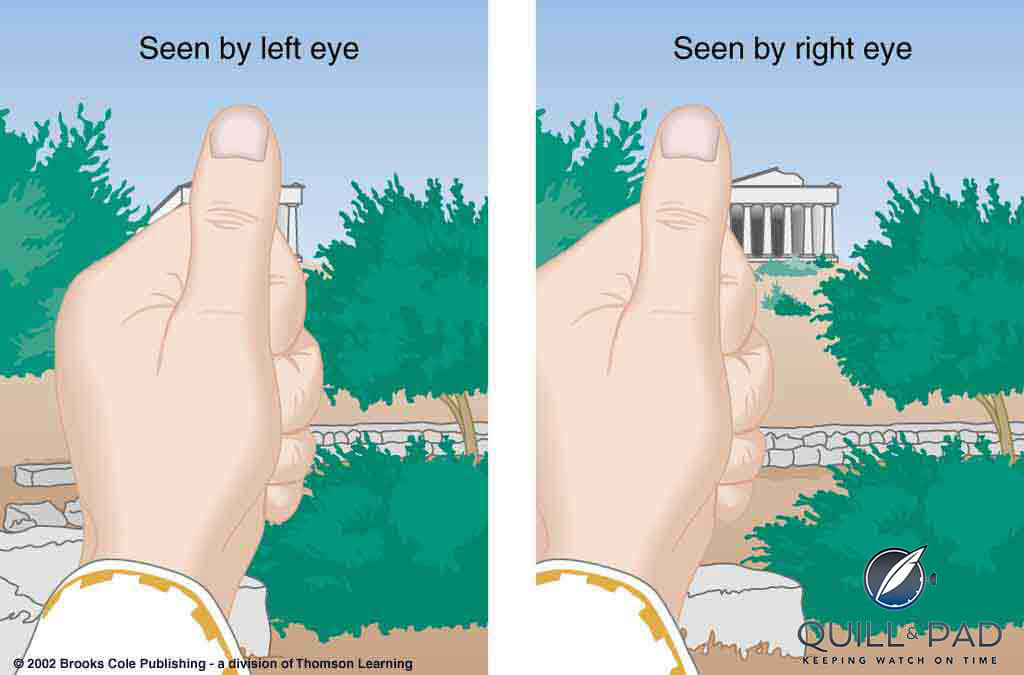

This phenomenon can best be seen by holding your index finger at arm’s length, closing one eye, and covering an object with your finger some distance away from you. Without moving your finger, switch eyes; suddenly that object is uncovered and your finger has moved. Parallax in action. How many of you just tried that? Kudos to those who did!

Fascinating phenomenon

Parallax is a fascinating phenomenon that has real-world applications, including the amazing ability of humans to use their two eyes and parallax shift to judge depth of field. You can reach out and grab that doorknob because of science.

For this reason and more I absolutely love the latest creation to come out of the Grönefelds’ workshop, their aptly named Parallax Tourbillon.

Let’s get straight to the point: why parallax? Good questions deserve good answers. When viewing precision-measuring instruments such as micrometers or dial gauges, parallax error needs to be taken into account lest you make an inaccurate reading.

You might look at the scale and pointer from an oblique angle and read that it is .008 instead of the .006 that it actually is. Critical measurements require precise readings. The same applies to time-measuring devices, in this case, a very accurate tourbillon settable to the second.

Setting to the second

The Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon features a newly developed system for setting the tourbillon to the second, and with that accuracy comes the need to be able to read it correctly. As we just established, the name of the piece originates from the need to eliminate any reading issues resulting from parallax error.

The seconds’ chapter ring, therefore, was raised as high as possible and situated only .05 mm below the second hand. For those not familiar with the metric system, less than two-thousandths of an inch separate the chapter ring and the blued second hand.

To compare, standard printer paper is about twice as thick at around .091 mm. Based on my hands-on assessment, the problem of parallax error has been more than eliminated.

The gap between the second hand and chapter ring on the Parallax Tourbillon is minimized to reduce parallax error

But what facilitated the need for such accurate reading? The tourbillon, of course. Not just any tourbillon, but a hacking flying tourbillon settable to the second. Setting takes place via the crown, but not in a traditional way: the Parallax Tourbillon features a push-to-set, push-to-wind mechanism similar to a column-wheel chronograph, which utilizes a few clever levers and an integrated star wheel.

The star wheel allows for four changes between modes in one revolution of the wheel, while also changing a mode indicator and hacking the tourbillon and second hand.

Even more interesting is that it doesn’t instantaneously stop the delicate tourbillon, instead opting to stop it when it naturally reaches its zero position and the second hand reaches 12 o’clock at the top of the dial. This way you are always starting from the top of the minute with your precise synchronization.

It achieves this function with one of those clever levers I mentioned earlier. When you press the crown to switch to setting mode, a lever shifts into position to catch a pin attached to the tourbillon cage. That pin allows the tourbillon and second hand to be stopped when it naturally interferes and come to rest at the same spot every time.

You can set the hours and minutes while the tourbillon comes to rest, or you can wait until it is at rest, set the time, and then press the crown to release the tourbillon and synchronize it all for an accurate time-measuring device within C.O.S.C. chronometer standards.

Accuracy for accuracy’s sake

Not many watchmakers actually discuss their tourbillon’s accuracy while still claiming to have made the mechanism for accuracy’s sake. This is also where the Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon stands above much of its competition: it holds itself accountable as a piece of precision equipment.

For this reason, the Grönefeld brothers also modified a long-held standard component for a central second hand. In most pieces with a large central display of seconds, a friction spring is needed to cancel out any free play in the gear train for a smooth sweep of the second hand. This robs the movement of energy and creates unnecessary wear.

To avoid this, the brothers removed that spring and added an intermediate pinion and wheel to tighten up the gear train and reduce power consumption. This results in a boost for the power reserve up to a very respectable 72 hours.

So while the Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon has more than enough geekery inside to keep me giggling for hours, it also excels in the looks department. The flying tourbillon with a single-sided bridge arm is raised as high as possible and framed by a perfectly polished ring to show off the finely finished mechanism.

The solid silver dial is very clearly Grönefeld through and through with frosted surfaces, polished bevels, and circular grained rings reminding anyone of the now-classic One Hertz model.

Flipping over the familiar case reveals a new take on the Grönefeld bridges, though still featuring the relief details, polished edges, satin-blasted recesses, gold chatons, and ample bridge real estate. All in all, just looking at this thing makes me happy. Then I am lucky enough to remember what is inside and I become happier still!

For my first Baselworld debut piece, it’s a dang fine start. So let’s break it down!

• Wowza Factor * 9.35 The tourbillon combined with true Grönefeld “DNA” makes for a pretty big Wowza anyday.

• Late Night Lust Appeal * 71.234 gn » 698.566m/s2 Just about twice as much as a human can sustain on a rocket sled, this piece rockets me into my chair so fast I can barely lift my head to say how much I want it!

• M.G.R. * 65.48 Grönefeld bridges – check! Ingenious setting mechanism – -check! Tourbillon settable to the second – check! Sounds like quite a piece we have here.

• Added-Functionitis * N/A If this category was Added-Awesomitis we would need immediate emergency room care. But as it is technically just time only, there won’t be any need for a tube of Gotta-HAVE-That cream. I still love it, though.

• Ouch Outline * 11.7 – A Door Falling Off its Hinges and Hitting You on the Noggin This would hurt, I don’t care who you are. But if I knew that afterward I would get a chance to acquire this piece, I may just purposefully stand in the way of that door!

• Mermaid Moment * Push to set, push to wind Knowing that this mechanism is brand new and designed just for this one model makes me smile, feeling it work so perfectly makes me book a florist.

• Awesome Total * 846 Add the alloy of the steel-cased version (316 stainless) to the alloy of the gold-cased version (750) and subtract the result from the model number of the stainless case (1912 for the year the brothers’ grandfather began his business as a watchmaker).

Quick facts:

Case: 43 x 12.5 mm, stainless steel (1912 model) or red gold

Functions: hours, minutes, sweep seconds; power reserve indicator; winding/setting function indicator

Movement: manually wound Caliber G-03 with flying tourbillon

Limitation: 12 pieces in stainless steel; 28 pieces in red gold

Price: limited edition stainless steel €134,250, limited edition in red gold €137,450 (directly from workshop without tax)

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

[…] may also enjoy Copernicus, Alignment Shift, And The Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon: A Nerd Story and Grönefeld One Hertz – A Collector’s […]

[…] Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon. (See Copernicus, Alignment Shift, And The Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon: A Nerd Story for more information on […]

[…] Further reading: Grönefeld 1941 Remontoire In The Horological House Of Orange and Copernicus, Alignment Shift, And The Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon: A Nerd Story. […]

[…] and Bart Grönefeld are great watchmakers; their Parallax Tourbillon took the prize for Best Tourbillon at the 2014 GPHG, and I predict that their 1941 Remontoire will […]

[…] Collar: Bart and Tim Grönefeld (see Copernicus, Alignment Shift, And The Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon: A Nerd Story for more information on the Grönefeld Parallax […]

[…] tourbillons: 1. Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon (See Copernicus, Alignment Shift, And The Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon: A Nerd Story.) 2. H. Moser & Cie Venturer Tourbillon Dual Time 3. Harry Winston Histoire de Tourbillon 5 […]

[…] To find out more about the Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon, please read Copernicus, Alignment Shift, And The Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon: A Nerd Story. […]

[…] Here is a great article discussing this Gronefeld watch: http://quillandpad.com/2014/04/20/copernicus-alignment-shift-and-the-gronefeld-parallax-tourbillon-a… […]

[…] Here is a great article discussing this Gronefeld watch: http://quillandpad.com/2014/04/20/copernicus-alignment-shift-and-the-gronefeld-parallax-tourbillon-a… […]

[…] and stainless steel bridges. For more information, check out Joshua Munchow’s article Copernicus, Alignment Shift, And The Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon: A Nerd Story. […]

[…] Beginning of this year, Ian Skellern and Elisabeth Doerr, started their blog Quill & Pad (yes it’s about watches) and soon they asked Joshua Munchow to join them. Joshua is Quill & Pad’s “resident nerd-writer” as he labels himself. The other day he did a magnificent article on one of my favorite new watches of this year, the Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon. Click through to read his brilliant write-up: Copernicus, alignment-shift, and the Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon: a nerd story. […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!