I went to the theater recently and saw a typical raunchy comedy called Neighbors. Much to my surprise, I saw something I cannot remember ever seeing in a mass-marketed movie: a 3D scanner and 3D printer being used by the main characters in a funny circumstance. (For said circumstance, please watch the movie because it cannot be discussed here.)

This made me realize that I was witnessing the total assimilation of 3D printing into popular culture, as it is now ubiquitous enough to be a funny joke in a low-brow comedy.

Why is this important? There are many reasons to be sure, but what stuck out to me as someone who has used the technology for years is the accuracy and simultaneous lack of accuracy depicted in the film. For that I blame any and all magazines that tout 3D printing as a completely new revolution that will change the way everyone lives from here until eternity.

As with most technology, there is always more than meets the eye, and 3D printing is no different. While many may have heard about it and know a small amount of detail from articles or videos, most take headlines as fact, and as such a bit of mystique surrounding 3D printing has emerged.

So much so that companies use the term as a buzzword in advertising to show that they are on the cutting edge of fabrication technology. While this isn’t necessarily incorrect, the facts about the technology paint a very different picture; one that might enlighten many consumers, including all of us watch nerds.

Today I would like to take a look back at the history of 3D printing and talk about the technology and how it is used for various purposes. It might shed some light on why it is so amazing, why it might not revolutionize manufacturing just yet, and why further advancements will be eagerly awaited by many industries around the world.

Not a new technology

First things first: 3D printing is not new even if it has not yet become a buzzword in watchmaking. Not by a long shot. The origins of the concept were born in the mid-1800s with a variety of processes used in photography, map making, and sculpture.

And while it took more than a century, the first functional 3D printer was developed by Chuck Hull in 1984.

Yeah, 1984

The same 1984 that George Orwell wrote about.

The selfsame one that saw the emergence of the first Apple Macintosh, witnessed the Soviet Union (still in existence) boycott the summer Olympics, and the one in which we learned that it’s nice to wake me up before you go-go.

It also happens to be around the same time that desktop publishing was invented. This is actually a good technology to compare with as it saw a similar, albeit faster, rise in popularity and eventual domination of its position as a consumer-level technology.

The technology behind 3D printing is actually much more complicated, thus taking a while longer to develop to a highly functional level like we see today. Well, sort of, but I will get to that later.

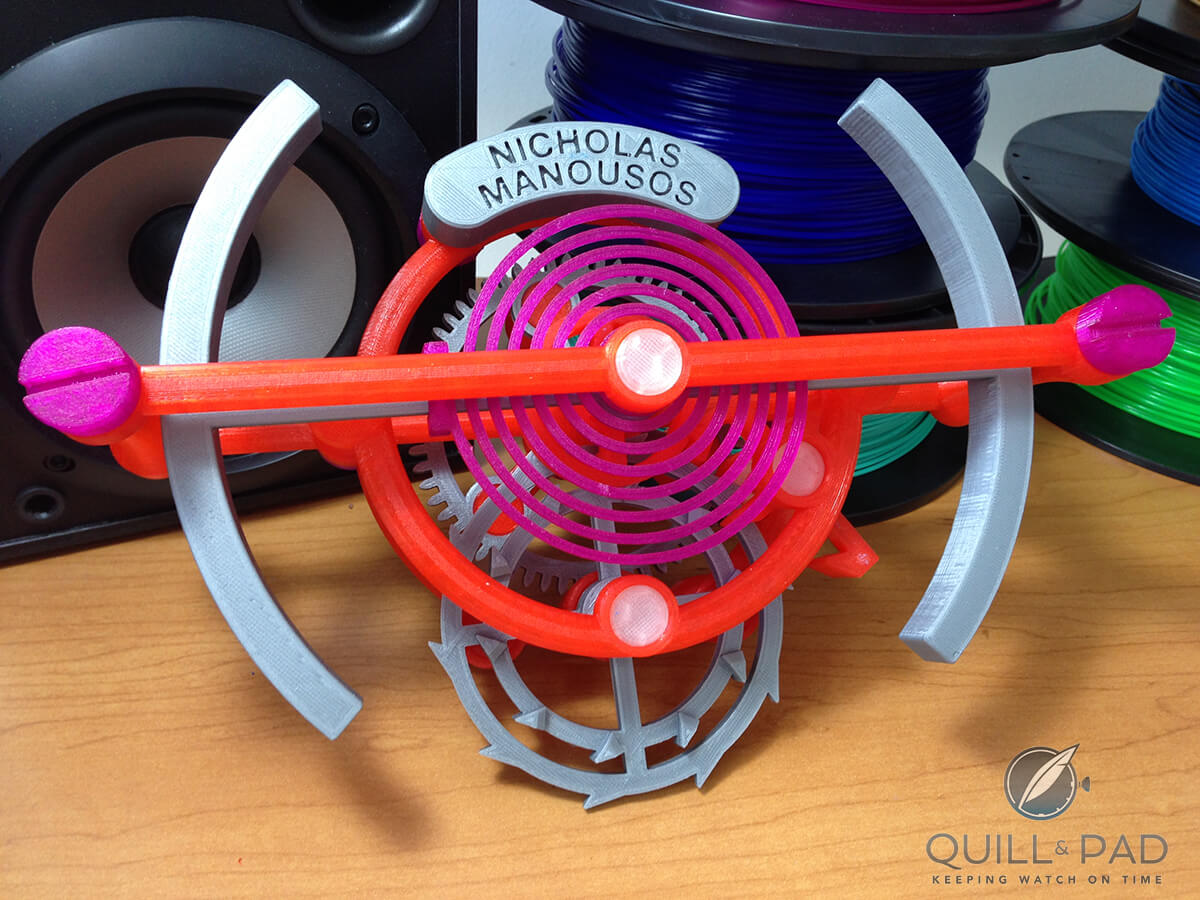

Brightly colored, fully functional model of a tourbillon with co-axial escapement designed by independent watchmaker Nicholas Manousos

What is it, actually?

Easy answer: it is a printer that “prints” objects in three dimensions instead of as an image on paper.

More complicated answer: a 3D printer is a general term for any device that uses additive manufacturing techniques to produce an object using a build material and a 3D CAD model that is fundamentally an enormous list of points in three-dimensional space.

Basically, a 3D printer takes data from a 3D CAD (Computer-Aided Design) model and translates that information into points where it needs to put material to build the object.

How each machine does that depends on the type of machine it is.

That is where this gets a little more complicated. Additive manufacturing, or the process of manufacturing whereby material is added to an empty build surface or table to create structure and shape, is achieved using a variety of processes.

To compare: the majority of manufacturing is subtractive, i.e., we start with a large block of material and mill off what we do not want to end up with the final form.

The main types of additive manufacturing use four methods for creating their shapes: melting and extruding, curing, binding, or fusing.

The first 3D printer used a process called stereolithography (SLA), which is very much in use today. In this process, a vat of liquid photopolymer (light-sensitive plastic) is exposed to a concentrated beam of ultraviolet light that draws a single layer of the object onto the surface of the liquid.

This cures the photopolymer, and a solid slice of the object is now a reality. After the first layer is completed, it is fused to a support platform that moves the thickness of a single layer down and the process repeats.

Successive layers are built up until a fully formed object is created, usually consisting of hundreds or thousands of layers anywhere from .05 mm to .15 mm in thickness.

This creates a generally solid, transparent plastic part that has very fine detail and can be used for prototyping or, depending on application, as the final part.

Inkjet, Polyjet

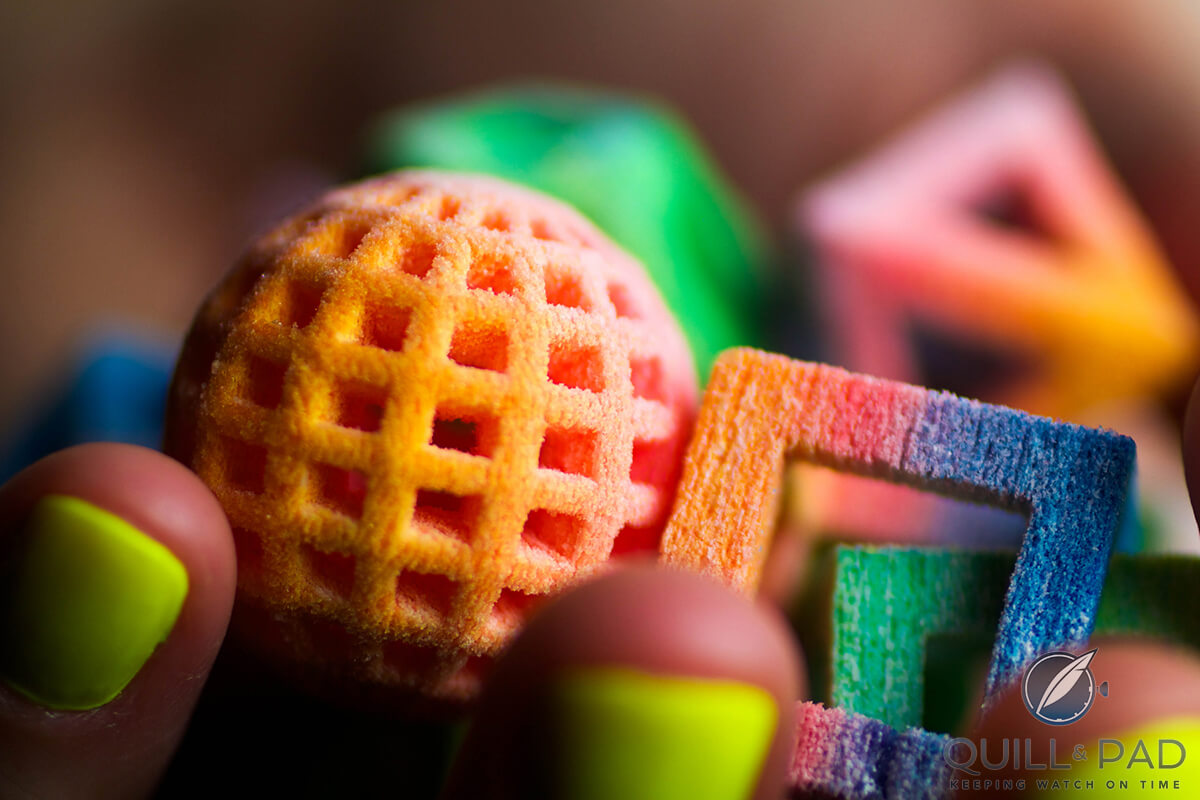

A process that is similar to an actual printer is powder bed and inkjet 3D printing. It was invented by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and was exclusively licensed by Z-Corporation until very recently. For this reason I (and most people I know) call this process Z-Corp printing.

In this process, an extremely fine plaster like powder is spread over a moveable table that supports the model. An inkjet-like head moves over the powder and prints onto the powder with a liquid “binder” that acts as a type of glue.

In reality, the binder is actually made up of a material similar to Super Glue, which is nothing more than cyanoacrylate.

Like SLA printers, inkjet-type printers build in many tiny layers usually around 0.1 mm thick, and it takes hundreds or thousands of layers to create an object. The benefits are that it is the fastest of the printing processes. And the cheapest as the base materials are nothing too special.

A recently developed process called Polyjet, which is also the machine name and trademark, combines the best of both SLA and Z-Corp printing. It uses an inkjet-like head with an attached ultraviolet light and prints using a photopolymer laid directly onto a support platform. The ultraviolet light cures the photopolymer as it prints, which allows much more control over the printing process.

This configuration eliminates the need for a vat of liquid in the print area and allows the printing of a variety of materials as it can jet out two different materials at once.

This machine, in its more advanced forms, can also print soft rubbers on top of hard plastics, add more material options, and combine them during printing to create numerous material configurations and properties. Also, the process is one of the more accurate, able to produce layers down to .016 mm thick.

The advantage of this process is a much more realistic product feel or, in low-run situations, a final product that contains all the features required of the product like a paintbrush handle with an over-molded rubber grip.

Moving on, we come to the process most people will be familiar with: Fused Deposition Modeling, or FDM. This process does away with photopolymers, binders, powders, and inkjet heads, but keeps the support table. FDM technology relies on solid thermoplastics (and a variety of less-used materials), which it heats up to their glass transition temperatures (temperatures between solid and melting) before extruding a fine filament from a nozzle head.

This allows the plastic to be squeezed exactly where it needs to go, similar to a baker piping out frosting onto a cake. Since it is not fully melted, it binds to and hardens on contact with the previous layers.

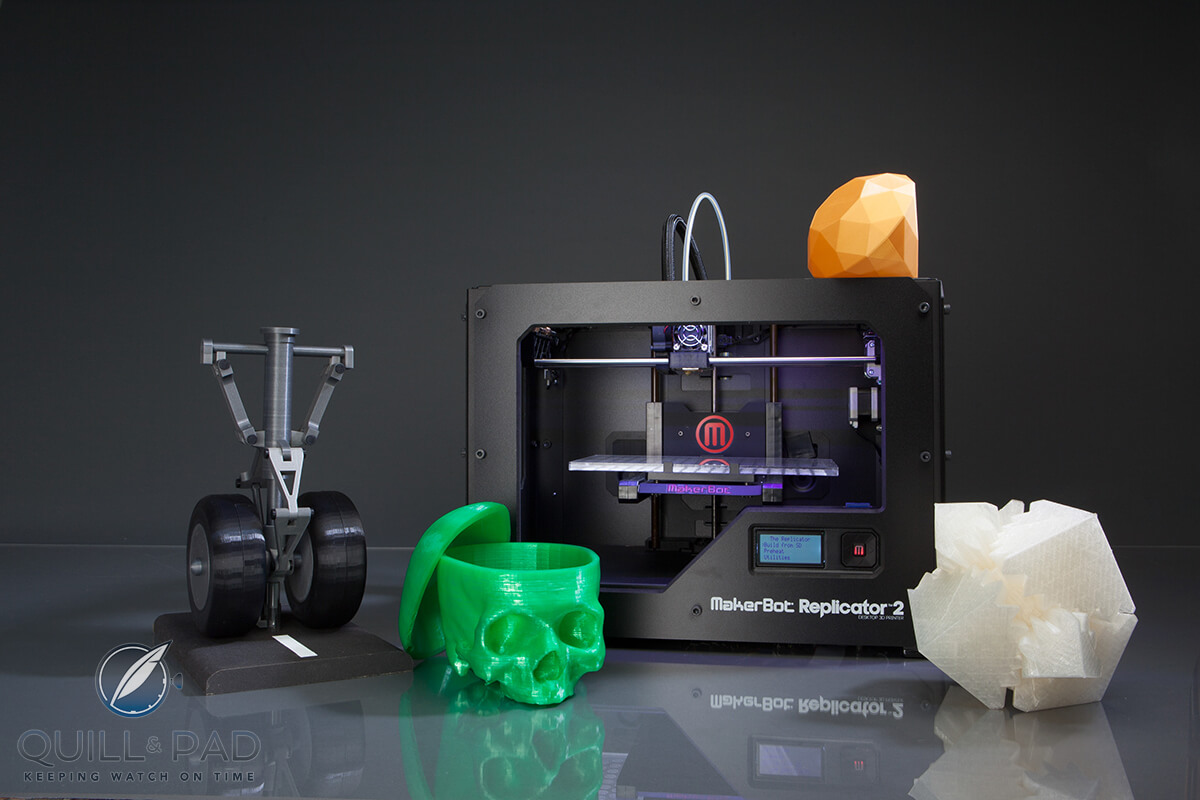

This technology is the bread and butter of the do-it-yourself movement and has been made popular by the MakerBot, Da Vinci, RepRap, and Cube machines, which are consumer-level versions of their much larger cousins. The most common thermoplastics used by FMD machines are ABS, PLA, HDPE and polycarbonate, which create different properties but overall strong, mostly solid structures.

Typical layer thickness ranges depend on price level and extrusion head but fall in the .3 to .07 mm area. This is also the type of machine that is infamously featured in that film I watched the other day.

Consumer costs

Before we take a well-earned respite from the deluge of technical facts regarding 3D printing, we should look at how much it costs. The machines are different than the process, as a 3D printer can range from $499 at the super low end for a consumer-level FDM machine all the way to millions of dollars for Polyjet, Electron Beam, and DMLS machines.

But that doesn’t tell us very much. How much does a part cost, or at least what could you expect to pay to have one made should you not want to invest in a machine?

That varies as well, but an SLA or FDM part that is small and straightforward might cost you a couple hundred dollars or less. Polyjet might grow up to over a thousand dollars and DMLS might be even more from a variety of service bureaus.

And note that the figures below don’t include the all-important file instructing the machine how to print.

But these are guesstimates, as size will play a role in addition to complexity (even though they say it doesn’t). Basically, costs are determined by how much raw build material your part will use, add a base rate for the service plus the time for the print, and any special considerations they need to make when dealing with your file.

These could range from difficult or complex geometry resulting in models requiring more material than they would otherwise need, and digital files that are corrupt or simply not usable for printing. Any extra effort on their part to adjust or work with your file past simply inserting it and hitting print will increase the cost.

Something as simple as a watch case would probably be on the low end of cost for whatever process you choose, as it is very straightforward and small. In fact, it is something that is right in the wheelhouse of 3D printing.

Large parts can really complicate things as the work envelope for most printers is surprisingly small.

No good service bureau will give you a flat rate for a part because there are many factors to look at before an accurate quote can be provided.

Ahh, such is the world of prototyping: a discipline full of guesstimates and assumptions that must be first tested before solid answers can be given.

In Part 2 we will discuss the realities of 3D printing as well as how it is used and why it is still not exactly the golden solution to manufacturing.

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] forward, plastics may end up being used even more as composites technology advances and 3D printing becomes more accurate and faster. In watch development, 3D printing is usually only used (at least […]

-

[…] Firstly, FEMTOPrint is a misnomer. The process does not involve printing in any way familiar to the additive manufacturing camp, but instead uses some concepts from 3D printing to create amazingly detailed glass structures (see Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really?). […]

-

[…] graphics could be printed into tangible, wax versions using a 3D printer. The next part is where ancient methods take over from the […]

-

[…] reading please see: 350 Processors And 90,000 Watts of Power Just To Mill A Curved Line? CNC Primer Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? Part […]

-

[…] a two part series focusing on 3D printing and the technological applications for watchmaking (see Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? and Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? Part Deux), I discussed the variety of […]

-

[…] a two part series focusing on 3D printing and the technological applications for watchmaking (see Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? and Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? Part Deux), I discussed the variety of […]

-

[…] a two part series focusing on 3D printing and the technological applications for watchmaking (see Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? and Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? Part Deux), I discussed the variety of […]

-

[…] a two part series focusing on 3D printing and the technological applications for watchmaking (see Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? and Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? Part Deux), I discussed the variety of […]

-

[…] you found this interesting, you may also like Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? and Focus On Technology: 3D Printing, What Is It Really? Part […]

-

[…] out the full article here on Quill & Pad (be warned though, it is an intense […]

-

[…] SLS process starts out very similarly to the Z-Corp process I covered in Part 1 as it has a bed upon which a powdered material (including polymers, metals, ceramics, and […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Fascinating read, thank you!

Thank you for reading, Tim!

I am really amazed at your blog post, currently the scope of 3D printing has recently increased because of its dynamic designs and looks, here how we can get a 3D printed for our home is there any procedure for it.