Let Them Eat Cake: The Intriguing Story Of Marie Antoinette And Her Legendary Breguet Pocket Watch No. 160

She is one of the most famous women in the history of watchmaking, even though she never held a screwdriver in her hand.

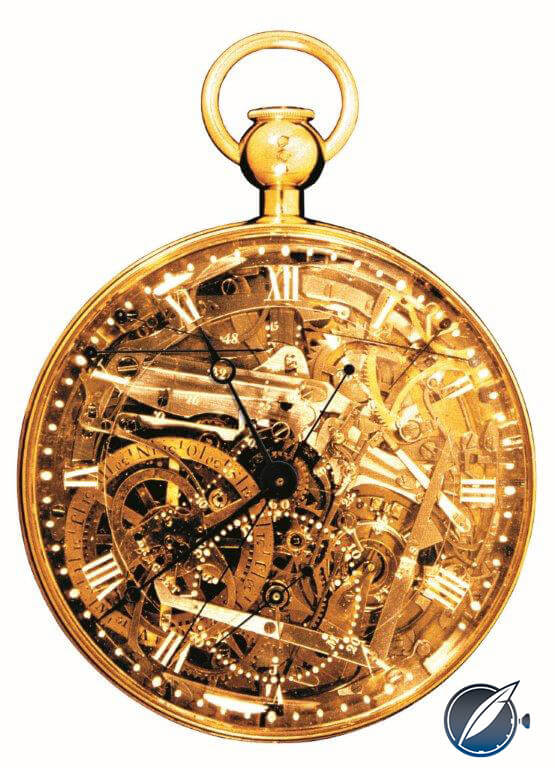

Breguet Grande Complication No. 1160

She is the main character in one of the most legendary watch stories ever told, even though her claim to fame is the loss of her head.

She is Marie Antoinette, ill-fated archduchess of Austria and queen of France, and this is her famous watch story.

The most complicated watch in the world at that time

In 1783, just as the queen of France, Marie Antoinette, was sitting for a (now famous) portrait being painted by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun – a replica of it still hangs in the Petit Trianon – an officer of the queen’s guard visited Abraham-Louis Breguet’s workshop at 51, Quai de l’Horloge in Paris with a challenging commission.

The most famous likeness of Marie Antoinette was painted by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun in 1783; it hangs at the Petit Trianon on the Versailles estate

The officer is believed to have been Swedish soldier Count Hans Axel von Fersen. He is also thought by some to have been Marie Antoinette’s lover, though there is no definitive historical evidence in either direction.

Breguet had left his native Switzerland in 1762, founding his famous workshop on the banks of the Seine in 1775. It was Abbot Joseph-François Marie, a man with close ties to the French court, who took the watchmaker under his wing, aiding him in establishing connections with those in power – including the queen of Naples, Caroline Murat (see Queen For A Day: Breguet Reine De Naples Haute Joaillerie), who bought 34 timepieces from Breguet throughout her lifetime, including the first wristwatch Breguet ever manufactured (see The First Wristwatches From Breguet, Hermès And Patek Philippe Were Made . . . For Women).

Abraham-Louis Breguet’s first workshop on Paris’s Quai de l’Horloge

The Queen of Naples was undoubtedly influenced by choices that the French queen had been making since her first commission with Breguet in 1782, which was for an automatic-winding pocket watch with calendar and repeater function.

But at the time of the officer’s visit to the workshop, it was clear that the queen was after something else, something quite a bit more complicated: Queen Marie Antoinette desired a pocket watch containing all known horological complications at the time.

And above and beyond that, wherever it was at all possible within the movement, gold was to be used in place of the other, more usual metals such as brass.

Neither a delivery date nor a price was fixed, meaning that the watchmaker was basically granted carte blanche. Breguet, who also specialized in the first automatic movements, was likewise determined to enrich the timepiece destined that came to be known as “the Marie Antoinette” with his brand of automatic winding called “perpétuelle” – meaning whenever the wearer moved, the mainspring rewound.

Pocket watchicus interruptus

Meanwhile, a bit of kerfuffle at the French court had broken out. In 1792, the French monarchy was officially declared fallen and King Louis XVI was condemned to death and executed the following year in the first steps of the French Revolution.

Marie Antoinette was taken to prison in 1792 and ultimately executed by guillotine in 1793. Ever the fashionista, she continued to demonstrate loyalty to Breguet by commissioning a “simple Breguet watch” while held at Temple Prison.

On a personal side note, I’m not sure why Breguet would have accepted this particular commission as he was very unlikely to receive compensation.

However, in terms of pocket watch number 160 – the “Marie Antoinette” – I can fully understand why he would continue the laborious work on this as it is now one of the most legendary timepieces in history; though he couldn’t know it at the time, it added immeasurably to the legacy of the most famous watchmaker in history. And, Breguet was most certainly sure he could sell it to another client, which he in fact did.

This Adolf Ulric Wertmüller painting of 1785 entitled ‘Queen Marie Antoinette and Two of her Children Walking in the Park of Trianon’ clearly shows two watch fobs hanging from her waist (photo courtesyWikipedia)

Breguet began work on pocket watch number 160 with enthusiasm. It was ultimately completed in 1827, four years after his death in 1823, which was 34 years after Marie Antoinette’s death, and 44 years after its initial order.

The reason for the lengthy delay in completing the oeuvre was the French Revolution.

In 1793, revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat, who likewise hailed from Neuchâtel, found out that his friend Breguet had also been marked for the guillotine, most likely due to his ties to the royal court. He however escaped to Switzerland before continuing on to England, where he spent two years working for King George III among other things.

When France’s politics had stabilized in 1795, he returned to Paris and once again set up on Quai de l’Horloge, where he continued work on pocket watch number 160 – though French politics were not as stable as he would have liked and interruptions occurred again and again.

Abraham-Louis Breguet’s gravesite at Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris

Official Breguet communication states that a note he wrote in August of 1823 confirmed that this project was still on his bench and his intention was to finish it soon.

While his death on September 17, 1823 ended that hope, Breguet’s watchmakers under the direction of his eldest son, Antoine-Louis Breguet, finally celebrated the project’s completion in 1827 – a date also confirmed in Breguet: Art and Innovation in Watchmaking, published by the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco on the occasion of the “Breguet Art and Innovation in Watchmaking” exhibition, which ran from September 19, 2015 to January 10, 2016 at the Legion of Honor (see You Are There: Breguet’s Art And Innovation In Watchmaking Exhibition).

However, a different viewpoint on this historical timing exists, which I describe below.

An extraordinary piece of horology

Breguet’s pocket watch number 160 is nothing if not captivating in every extraordinary detail.

Abraham-Louis Breguet’s original pocket watch No. 160, which was commissioned in 1783 for Marie Antoinette, then queen of France

The automatic pocket watch wound by a platinum oscillating weight was equipped with the following indications and functions: minute repeater; perpetual calendar displaying weekday, date, month, and leap-year cycle; equation of time; power reserve display; metal thermometer; independent central second hand (stopwatch function with no reset ability); and a small second hand.

Breguet scholar and legendary watchmaker George Daniels asserts in his 1974 book The Art of Breguet that the base movement was made by “Prudhomme.” Though Daniels did not specify Monsieur Prudhomme’s first name, it is likely true as Breguet was known to hire accomplished watchmakers outside his workshop, and I would trust Daniels implicitly to recognize whose work he was looking at.

Back of the Breguet Grande Complication No. 1160 with the large automatic winding mass on the left

Alongside Breguet’s signature double pare-chute shock protection, this watch also boasted a hairspring made of gold and sapphire jewel bearings and rollers. The plates and bridges and all of the gear train wheels comprising the calendar, repeating, and going trains were crafted in pink gold.

It needed two dials to display everything: one was crafted in white enamel, the other in transparent rock crystal. Rock crystal was also used for the front and back crystals.

A rock crystal dial is placed over the movement of the Breguet Grande Complication No. 1160

Reported costs to make the watch bandied about on the Internet and elsewhere range between 17,000 and 30,000 gold francs. Daniels wrote the following about the cost of its manufacture as well as the timing of completion in The Art of Breguet , “Although it has been said that the watch was completed in 1802, a study of the workbook shows quite clearly that it was not finished until 1820, by which time it had cost 16,864 francs. The gifted pupil Michel Weber made most of the mechanism, for which he was paid 7,250 francs for 725 hours of work between 1812 and 1815.”

Weber and this period of industrious work were also mentioned in Breguet: Art and Innovation in Watchmaking; the book also confirms Daniels’s description of the costs.

The Marie Antoinette’s succession of ownership

The initial sale was reportedly not recorded in the company’s archives; however what was recorded was that in 1838, the aged Marquis de la Groye – who had been a page to the queen in his youth – sent the “Marie Antoinette” watch to the workshop for maintenance. But as luck would have it, the watch was never retrieved as the marquis passed away without leaving an heir.

The information above came from several sources, some or all of which may stem from a press release from Breguet from about 2004.

Be that as it may, Daniels asserts that Breguet’s family kept the watch until its sale to Sir Spencer Brunton. “Breguet did not sell the watch upon completion but retained it himself,” Daniels wrote. “It remained in the family until the widow of Louis-Clement Breguet, the last to run the business, sold it in 1887.”

I would not like to comment on which version is correct; I only desire to mention that there are two variations of that part of the story from reputable sources.

From this point, however, the ownership succession becomes quite clear: English collector Brunton had the honor of becoming its new owner in 1887, acquiring it for £600 (confirmed by Daniels). After Brunton’s death, his brother retained ownership after which it was sold to Murray Marks (1840-1918), a well-known art collector of Dutch heritage who lived in London from an early age.

Marks, who apparently owned 20 Breguet pieces throughout his collecting career, knew both Brunton and Sir David Lionel Salomons among other great art collectors of the time. Salomons, a scientific author and lawyer, was enamored of the study of horology. In 1921, he published the first major work on Breguet’s life and career ever written. He also managed to amass the largest private collection of Breguet timepieces in the world, comprising 124 pieces.

Marks’s collection of Breguet works was sold at Christie’s on June 22, 1896 – at which time Salomons acquired them.

The “Marie Antoinette” thus became part of Salomons’s watch collection at the beginning of the twentieth century. Vera Salomons inherited a portion of the collection – including the “Marie Antoinette” – from her father in 1925.

Here, too, the story tends to be told a tad differently depending on who is telling it. One version, which is retold on Wikipedia, states that Salomons himself bequeathed 57 of the pieces from his collection (including the “Marie Antoinette”) to the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem on his deathbed.

The remainder was maintained by his surviving wife, who took them to Sotheby’s to be auctioned, “although on her first visit she was reportedly dismissed from the office because the Sotheby’s staffer could not believe that anyone could possibly have owned such a collection. The timepieces were subsequently sold at auction for considerable sums,” it states there. (Please remember that Wikipedia entries can be written and edited by anyone.)

Another version (also found on the Breguet press release) states that Vera Salomons had developed a close friendship with a professor at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, Professor Leo Aryeh or Arie Mayer, who was an Islamic art enthusiast. She donated all the Islamic art she owned to a new museum she established in 1974 in honor of the memory of her friend: the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art. She also donated the horological objects her father had collected.

Daniels doesn’t weigh in on the discrepancy here, though in his autobiography All in Good Time, he did write that he strongly objected to the pieces being taken out of Europe and sent to Jerusalem – until the museum asked him to write the collection’s catalogue.

Either way, the “Marie Antoinette” came to rest in a museum in Jerusalem – but only for nine years as an unknown thief broke into the inadequately guarded Museum for Islamic Art on April 15, 1983, stealing 106 items, including the entire watch collection. At this point in time the “Marie Antoinette” was estimated to be worth $30 million.

This was the most expensive crime ever committed in Israel’s history. And a credible motive for this apparently random theft had never been discovered.

Cover of the novel ‘The Grand Complication’ by Allen Kurzweil

A fictionalized account of the mystery can be read in the highly entertaining novel The Grand Complication by Allen Kurzweil.

The plot thickens

The case went unsolved for almost 25 years until November 2008 when a Tel Aviv antique appraiser contacted the museum to explain that some of the stolen items were being held by a lawyer in Tel Aviv whose client, one Nili Shamrat living in Los Angeles, had inherited them from her deceased husband and wished to sell them back. The museum paid $40,000 to her to get 40 of the stolen items back.

A later search turned up documents leading to the recovery of all the items in safety deposit boxes in Israel, Germany, Holland, France, and the United States.

Shamrat was married to Naaman Diller, a lone burglar who discovered that the museum’s alarm system had not been working. Using a crowbar, he simply slinked past bars he bent on a rear window and removed the items. On his deathbed the serial thief confessed the crime to his wife.

You can read a full account of the mystery solving in The Guardian’s Police solve 25-year-old mystery of Marie Antoinette’s watch.

The Breguet brand also confirms that Swatch Group co-founder and chairman Nicolas G. Hayek received an anonymous message in 2007 with an offer to sell him the original. Hayek verified and discussed with the police, but in the end refused to enter into an illegal transaction. Twelve months later, it was returned to the museum in Jerusalem.

The Swatch Group replica: Grande Complication No. 1160

Nicolas G. Hayek’s Swatch Group acquired the Breguet brand in 1999. But it wasn’t until 2004 that Hayek decided it was time to build a replica of the fabled watch.

Breguet Grande Complication No. 1160

The technicians in charge had to make their calculations based solely on the few available documents; their sources included archives and original drawings from the Breguet Museum, the Breguet archives, and the Musée des Arts et Métiers in Paris. Further details were gleaned from comparative scrutiny of important historical timepieces made by Breguet’s workshop.

Developing the Breguet Grande Complication No. 1160 movement required comprehensive historical research

On the basis of know-how acquired in this way, they created a pocket watch that duplicated the mythological “Marie Antoinette” as closely as was possible. The Grande Complication No. 1160 made its debut in 2008 at Baselworld.

Meticulously assembling the movement of the Breguet Grande Complication No. 1160

This “Marie Antoinette” of the twenty-first century is likewise an automatic pocket watch with minute repeater and perpetual calendar. The date is shown at 2 o’clock, the weekday at 6 o’clock, and the month at 8 o’clock. The equation of time is displayed at 10 o’clock, while an independent second hand sweeps the dial. Its bimetallic thermometer is accompanied by a power reserve display at 10:30.

The movement comprising 823 components has a 48-hour power reserve and contains plates, bridges, and wheels made of wood-polished red gold.

Abraham-Louis Breguet is further commemorated by the choice of using of his “natural” escapement, a bimetallic balance, a cylindrical hairspring made of solid gold, and the double pare-chute shock absorption system.

Swatch Group co-founder Nicolas G. Hayek (1928-2010) holding the Breguet Marie Antoinette Grand Complication No. 1160

The yellow gold of its 63 mm case was cast in a special, more coppery alloy to order to match the hue typical of the queen’s day more precisely. Like the original, all crystal components are crafted in rock crystal rather than today’s prevalent sapphire crystal.

Presently, the Grande Complication No. 1160 is not for sale.

Hayek would certainly have gladly brought the rediscovered “Marie Antoinette” to Switzerland for maintenance at its “home” factory. Even though his offer was entirely free of charge, no such agreement could be reached with the L.A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art.

The modern replica of the “Marie Antoinette” had one other interesting side effect: it unexpectedly led to Montres Breguet financing the lion’s share of the massive restoration of Versailles’ Petit Trianon, the palace building on the Versailles compound originally completed in 1768 that the young Austrian queen called home in France.

Large blocks of timber from what was once Marie Antoinette’s favorite oak tree at the Petit Trianon on the Versailles estate

This came about when Hayek learned that Marie Antoinette’s favorite oak tree was about to be felled. Planted in 1683, it had grown to 35 meters in height and 167 centimeters in diameter. He offered to buy some of its wood to make the box to house the replica of the “Marie Antoinette.”

Swatch Group co-founder Nicolas G. Hayek (1928-2010) with the Breguet Marie Antoinette Grand Complication No. 1160 in its unique presentation case made of oak from the queen’s favorite tree

As the story goes, the Versailles estate was happy to offer it for free, but suggested the company support the restoration of a statue on the Versailles grounds. Hayek instead decided to finance the lion’s share of the restoration of the Petit Trianon and the Pavillon Français, which, according to The New York Times, cost $7.34 million.

The presentation case for the Breguet Grande Complication No. 1160 made from the timber of Marie Antoinette’s favorite oak tree

The case’s exterior reproduces the parquetry pattern at the Petit Trianon made from more than 3,500 individual pieces of wood. Inlay work depicting Marie Antoinette holding a rose (a detail of the above-mentioned portrait painted by Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun) comprises about 1,000 individual wood pieces.

Breguet Grande Complication No. 1160

For more information, please visit www.breguet.com/en/house-breguet/manufacture/marie-antoinette-pocket-watch.

Quick Facts Breguet Grande Complication No. 1160

Case: 63 mm, special 18-karat yellow gold alloy

Dial: rock crystal

Movement: automatic Breguet “perpetual” caliber comprising 823 components; plates, bridges, and wheels made of red gold; Breguet natural escapement with cylindrical gold hairspring

Functions: hours, minutes, seconds; perpetual calendar with date, month, and weekday; power reserve indication; equation of time; mechanical thermometer; minute repeater

Limitation: one unique piece

Estimated value: at least $10 million, but likely more

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

-

[…] world’s most historical figures as clients including Napoleon Bonaparte, Marie Antoinette (see Let Them Eat Cake: The Intriguing Story Of Marie Antoinette And Her Legendary Breguet Pocket Watch N…), and Sir Winston Churchill – to name a few – why not brag a […]

-

[…] You can read the entire history of Marie Antoinette and Breguet in Let Them Eat Cake: The Intriguing Story Of Marie Antoinette And Her Legendary Breguet Pocket Watch N…. […]

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

That’s an amazing article. I enjoyed reading it very much, thank you!

Thank you so much!

Fascinating to know how some timepieces become the ultimate reference for next generation watch makers

Thank you for such a precise and interesting read.

Thank you for reading!

Excellent article and thorough research.

Fantastic effort, Elizabeth

Thank you

Great read Beth.

I would add the following data, if you would allow, that will add to the speculation 🙂

First mention of nº 160 appears in a catalogue from 1827 regarding the “Exposition des products de l´industrie française, and “does not refer to the name Marie Antoinette.

In 1855 the 160 is mentioned again, regarding the Exposition Universelle of 1855, without any mention to Marie Antoinette.

Mentioned in 1861 regarding an exhibition at Besançon, again without any mention to Marie Antoinette.

Mentioned in 1904 in Old Clocks & Watches & their makers by FJ Britten, again without any mention to Marie Antoinette.

The first mention of Marie Antoinette is made by the London antiquarian Desoutter in 1917, probably to add interest to the watch and help it sell more easily considering the high amount that was asked.

– Chronology of ownership:

1838 – Marquis de la Goye

1887 – Edward Brow (owner of Breguet) sells to Spencer Brunton

1901 – Sidney Brunton

1902 – Murray Marks (The Marks Christies sale in 1896 did not include the 160)

1904 – Louis Alber Desoutter – antiquarian (probably not the owner as he sold it to Salomons on comission)

1917 – Sir David Lionel Salomons

1925 – Vera Bryce Salomons

1974 – Mayer Museum for Islamic Art

There were no Queens Guard but only the Kings Guard who also protected the Queen and the royal children.

Speculation ?:

The 160 was in reality destined for the King, maybe as a gift from the Queen. It is difficult to believe that a women in the 18th century would use such a complicated watch and in such a size (62 mm).

Thank you for that information, Carlos, which does indeed add to speculation in many ways. You mention some of your sources for this information . . . can you back up all of it with sources? I have proven the sources for all of my facts and told the story the way I see it using those sources. I am very happy to have more speculation on it, and I do like your final statement, which does sound plausible to me. It’s possible the Swedish soldier was added along the way (and he probably was involved with the queen) to make the story more interesting. I feel sure that the story was embellished here and there over the years to make the piece more interesting anyway – as most stories are.

But as for your comment about women in the 18th century using or not using complicated watches: both Marie Antoinette and the Queen of Naples were frequent customers of Breguet. The Queen of Naples even ordered Breguet’s first wristwatch, a repeater. So I have to kind of discount that theory because I think women of that ilk were different and definitely interested. But I would never rule out that it could have been intended as a gift for the king.

Now you are giving me some hard work 😉 All is documented and I guess you are referring just to the sources were the 160 is not associated to Marie Antoinette. The rest is common knowledge or my own speculation.

Sources:

First mention of nº 160 in a catalogue from 1827 of the “Exposition des products de l´industrie française”does not refer to the name Marie Antoinette.

– Source – Moniteur Universel de l´Industrie Française – NºIII – September 1827 – page 5

Mentioned again regarding the Exposition Universelle of 1855, again without any mention to Marie Antoinette.

– Source – Catalogue officiel publié par ordre de la Commission Impériale. Paris: [1855]. lvii, 448p. 1609/3853.

Mentioned in 1861 regarding an exhibition at Besançon, again without any mention to Marie Antoinette.

Source – La Loupe de l´Horloger Almanache – Borsendorf – 1861 – Page 78

Mentioned in 1904 in Old Clocks & Watches & their makers by FJ Britten, again without any mention to Marie Antoinette.

-Source – 2nd edition 1904 – pp. 364-365

The first mention of Marie Antoinette is first made by the antiquarian Desoutter in 1917

– Source – Breguet by Salomons – Page 4

There were no Queens Guard but only the Kings Guard who also protected the Queen and the royal children.

– Source – See Wikipedia: Garde du corps du roi

Axel de Fersen, the Swedish Count was mentioned by Napoleon as being involved with “l´ancienne cour de France”, so this part may actually be true. Again, just speculation here.

Regarding women using complicated watches in the 18th century, of course they used useful complications like repeaters, but I am suspicious that a mechanical instrument as the 160 would appeal to them. I am of course discarding woman of science as for example Caroline Herschel 🙂 On the other hand Louis was a lover of mechanics, locksmithing and “Horlogerie” 😉

Hey, nice work, Carlos!

You should read the fascinating research (still in progress I think) by Bernard Roobaert: https://issuu.com/bernardroobaert/docs/160

His hypothesis is that the real buyer was Charles-Eugène-Gabriel de la Croix de Castrie, father of the “Marquis de la Groye” (due to Breguet’s notorious bad spelling, Croix~~Groye), and, well, it is quite convincing…

But is doesn’t matter, I love the mythology as well as the (real?) story, and Marie-Antoinette is part of the story of this watch now, be it by chance.

Thank you so much for that link, which is fascinating! I will make sure to read it through. Just upon quick perusal of the first few pages at least most of his sources look good. It’s a great story, one that has always fascinated me.

Wow, what an interesting article, Elizabeth.

Thank you, Boris.