Wind & Water By Rick Hale: Wood, Wheels, And Wonderful Horology

A common idiom stating someone “can’t see the forest for the trees” means that it’s someone who looks too closely at the details and fails to see the bigger picture. This is quite common in scientific exploration, politics, and sometimes our everyday lives; we can get so wrapped up in the details of whatever we are focused on we lose sight of what’s important.

But here’s a new idiom that sort of piggybacks on the topic but goes in an entirely different direction. My brand-new idiom goes like this: “they could shape a beast from a birch.”

“They could shape a beast from a birch” means that a person can make something incredible from the most common materials. Basically, this idiom points out someone’s innate (or learned) ability to craft incredible objects with whatever is at hand.

With my new idiom defined, I present Wind & Water, a marvelous creation from clockmaker Rick Hale, a man that could shape a beast from a birch (see what I did there?).

We first shared one of Rick Hale’s creations, the KL1, in February 2019 and today we present his brand-new creation Wind & Water, a masterpiece in both horological and woodworking terms.

Unless you follow the incredibly small world of fine mechanical wood timepieces, the name Rick Hale may be new to you, so let’s remedy this fact before we dive into his awesome new project.

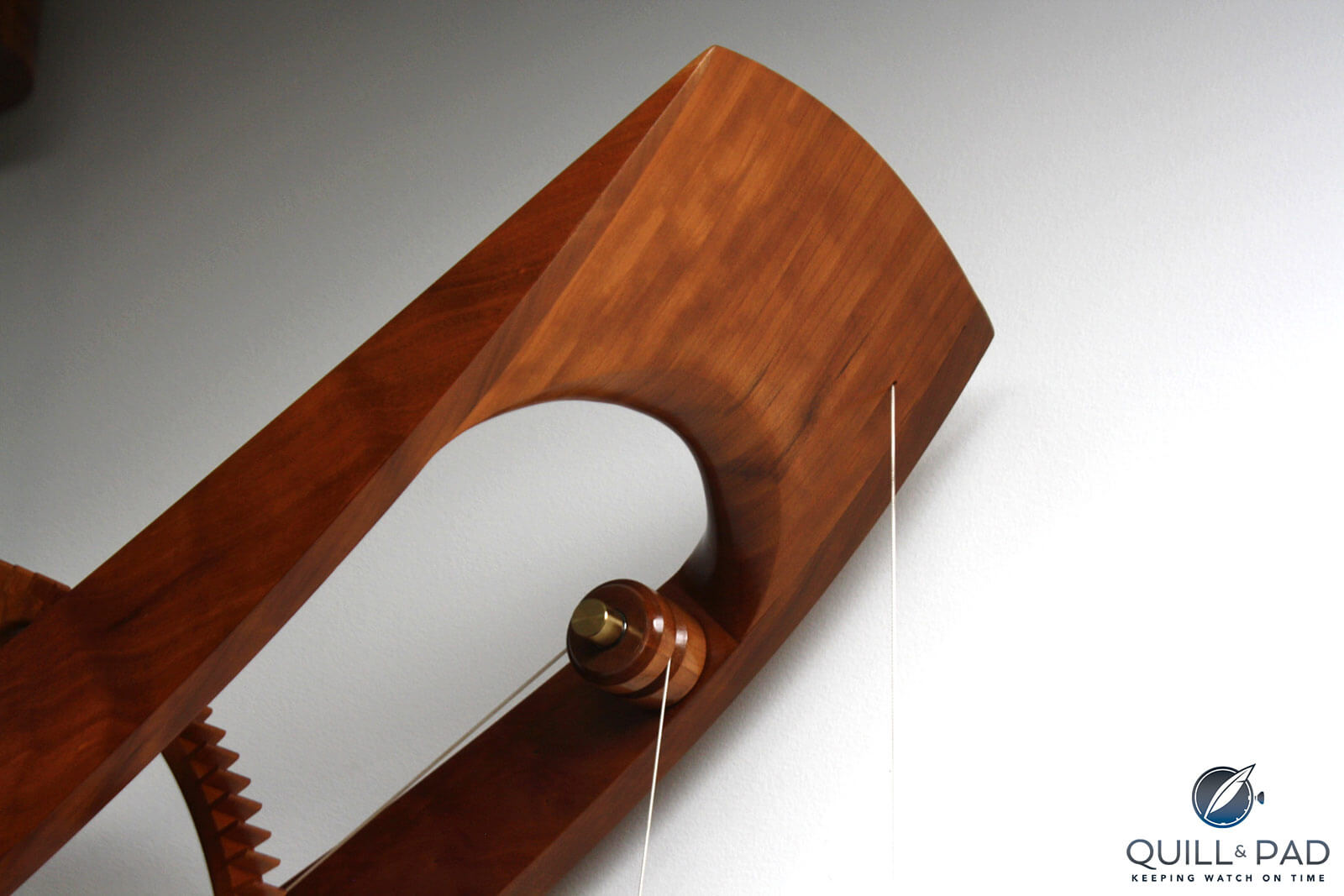

Detail of Wind & Water by Rick Hale

Clockwright Rick Hale

A native Michigander, Hale came to clockmaking via a rather indirect route. He graduated from Michigan State with a degree in English, thinking he might teach but discovered that it was not everything he had hoped. Without a specific direction in mind, he eventually got into woodworking as a hobby, however it blossomed into a full-blown career after a couple distinct events steered Hale in that direction.

The first was the loss of his father in 2012, an event that hit Hale hard and found him turning to woodworking as a way to cope and heal. Hale’s father, a mechanic, had instilled an understanding of mechanics in him that led to the second event: Hale’s first attempt at making a clock during this difficult time. Stating “it didn’t work; it was very, very bad,” in combination with the loss he was experiencing it made Hale question what he wanted to do with his life.

However, Hale dived into clocks, clockmaking, and learning about horology and the history behind it. Discovering the craftsmanship, precision, and wealth of information, he realized that he had found his type of people. Self-described as a perfectionist and a bit compulsive, Hale also realized he wanted to combine clockmaking and woodworking to find his own unique, creative voice. I would say from what he has created, we know he was successful in that respect.

Rick Hale shaping a wooden gear for his KL1 clock

Making clocks from wood also creates a lot of challenges, allowing Hale to be constantly problem solving and innovating with each piece. With a profound respect for John Harrison, inventor of the marine chronometer and accomplished woodworker himself, Hale set out to use classic principles from Harrison and others (Abraham-Louis Breguet, Thomas Tompion, Martin Burgess, etc.) to create stunning mechanical clocks made from ever variable hardwoods.

Wind & Water by Rick Hale

Wind & Water is the current incarnation of this desire and passion. It has a lot of nerdy mechanical and horological tidbits to geek out over, not to mention some fun woodworking details that add another level.

Rick Hale: Wind & Water

The name Wind & Water is derived both from the heritage of Harrison and the grasshopper escapement (and its crucial role in the development of the marine chronometer) as well as the aesthetics of the actual construction. It’s a departure from Hale’s usual naming scheme of a couple letters and numbers.

But, really, the naming is the least interesting aspect of Hale’s clocks and as Hale himself admits he would rather the clocks stand on their own. I think that they do.

Thin cable supporting a weight of Wind & Water by Rick Hale

Wind & Water, at its core, is a “simple” pendulum clock that displays hours and minutes with a pendulum oscillating at 0.5 Hz to create one swing every second (two seconds to make a full trip back to the starting point). The power reserve of the clock is 30 hours, making it a one-day clock requiring the driving weights to be wound every day. But if that were all the important details, we wouldn’t still be here.

What makes this clock so interesting is its mechanics and how they are implemented. And, of course, the materials with which the clock is made.

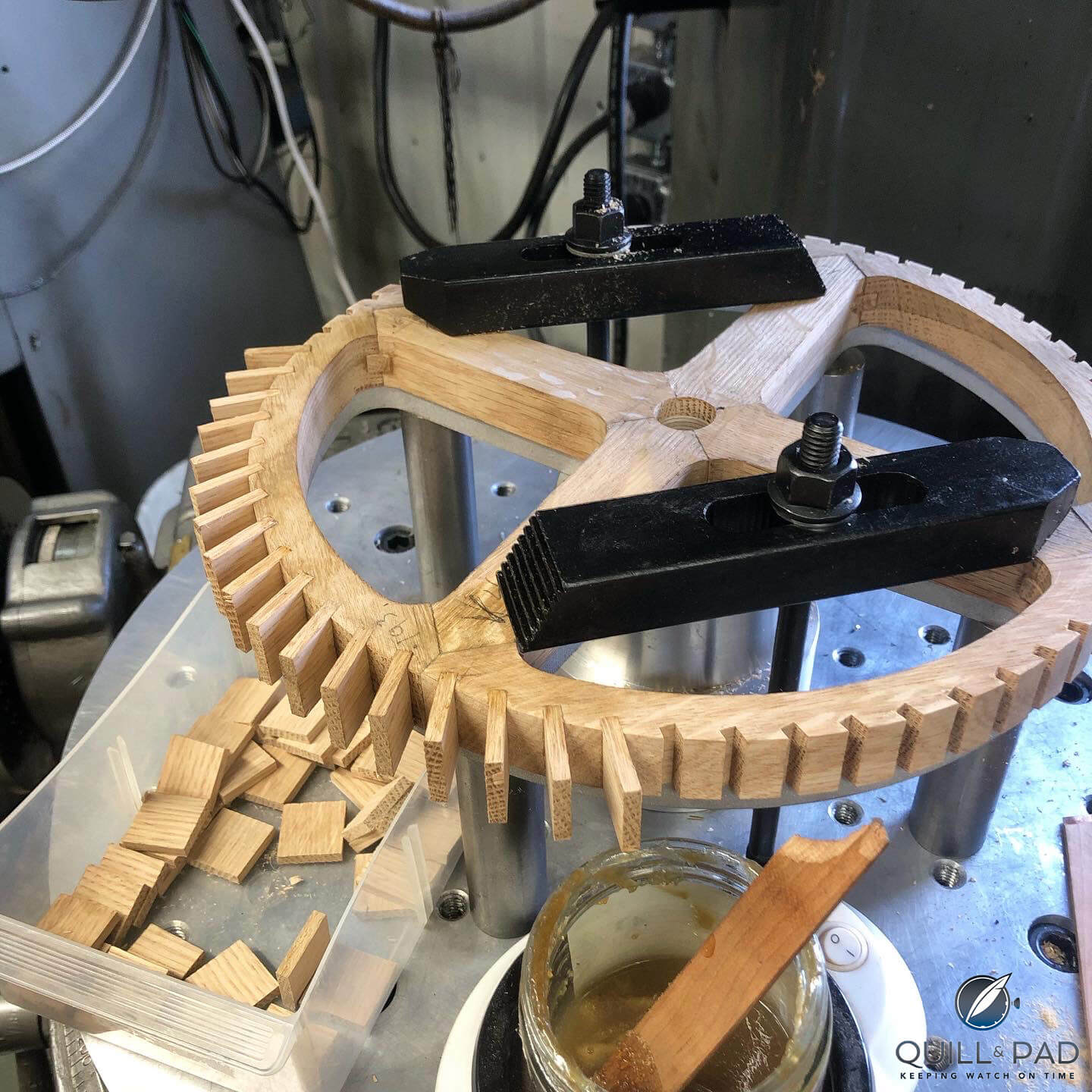

Rough shapes for the wood wheels of Wind & Water by Rick Hale

Let’s begin with the materials, shall we? The frame, pendulum, pulleys, driving weights, wheels, escapement, and even some springs are all made from solid figured cherry obtained from a local Michigan miller that picks out especially beautiful wood for Hale to use in his clocks. The ripples of light in the cherry match the theme of the clock and provide some extra visual movement to the already dynamic frame.

Maple hands of Wind & Water by Rick Hale

To help draw attention to the hands, Hale chose quilted maple for them, which also has gentle ripples of chatoyancy (the phenomenon of reflected bands of light such as is found in cat’s eye gemstones) to continue the water theme. Its light color sets it apart from the rich color of the cherry. The other wood variety used in the clock is one of necessity: lignum vitae.

This wood was famously used by John Harrison for bearings and gears in his first three marine chronometers and pendulum clocks due to its toughness and self-lubricating properties. As the densest commercially traded wood (and now regulated and somewhat restricted due to over harvesting and it being a slow-growing species), lignum vitae is a perfect choice for any bearing surface in wood clocks – or hydroelectric plant turbines, or even the propeller shaft bearings on the first nuclear submarine (true story).

Wind & Water by Rick Hale

Lignum vitae has centuries of wide use behind it, remaining an industrial material well into the twentieth century since it is naturally self-lubricating (so mostly maintenance free) and has a hardness of around 75 percent that of pure (unalloyed) aluminum. Hale uses this incredible wood for all the pinion rollers, bushings, and other bearing surfaces to avoid any need for lubrication, something that doesn’t match an entirely wood clock.

The only other materials used in Wind & Water are steel for some pins and pivots and brass for other shafts, counterweights, and sandwiched in ratchet wheels to prevent tooth breakage. Otherwise, Hale relies as much as possible on the wood to do all the hard work. Wood has its limitations, so Hale has had to modify classic designs to get around some structural weak spots.

These choices play right into the actual mechanisms of the clock, which are the coolest features in my opinion.

Grasshoppers and rollers

The most important horological features of the clock are the single-pivot grasshopper escapement, Hale-designed maintaining power gearing, the daisy wheel-style motion works (to drive the hands), and the use of chordal pitch gearing (inspired by Harrison), all of which have combined to create one very sweet mechanism.

As I mentioned earlier, the use of lignum vitae for pinion rollers comes into play with the chordal pitch gearing and requires very precise formation of the gear teeth and positioning but creates a smooth transfer of power.

It begins with the shaft of the grasshopper escape wheel (which I’ll get to in a moment) where instead of a typical involute pinion gear we find a set of lignum vitae rollers, literally cylinders made from the self-lubricating wood that pivot on steel shafts and act like gear teeth.

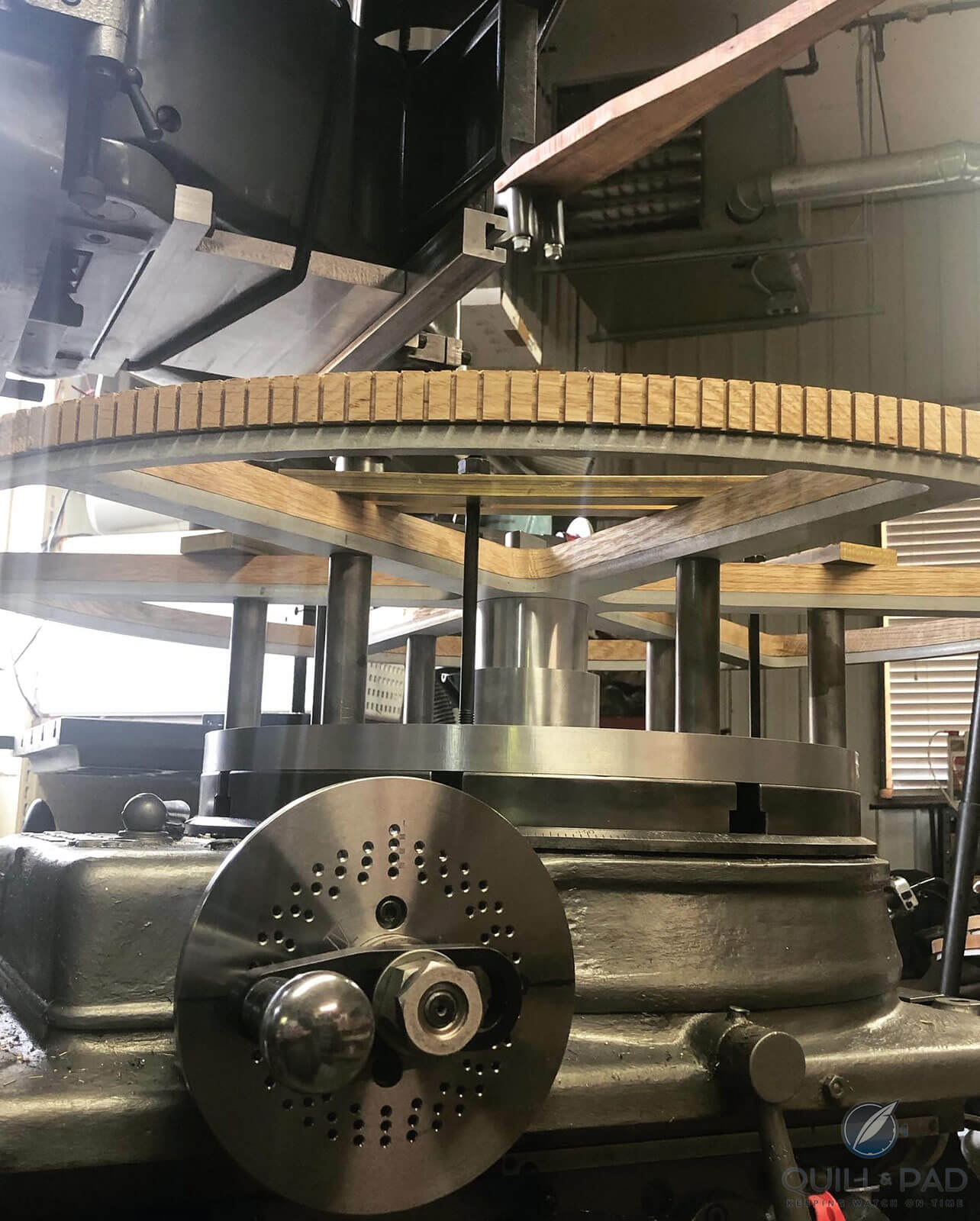

Making the wood escape wheel of Rick Hale’s Wind & Water clock

The large center gear uses individual slat-shaped teeth (with the grain running the length of the tooth for maximum strength) inserted into slots in the rim of the wheel. The precise spacing is calculated using chordal pitch, which utilizes the straight-line distance between two tooth centers. Chordal pitch is how chains and sprockets are measured, so the distance between each tooth directs the diameter of the pinion rollers for a perfect match between the teeth and rollers.

This eliminates pretty much all sliding friction between teeth since the rollers rotate almost friction free between the center wheel’s teeth as they mesh together. As I mentioned before, eliminating the need for lubrication was very important for Harrison and it is just as important for Hale. This is basically the entire reason the grasshopper escapement was invented in the first place, and why Hale gravitated toward it for his clocks.

The grasshopper escapement is surprisingly straightforward in operation for how clever it is and how it overcomes a lot of issues with other styles of escapement.

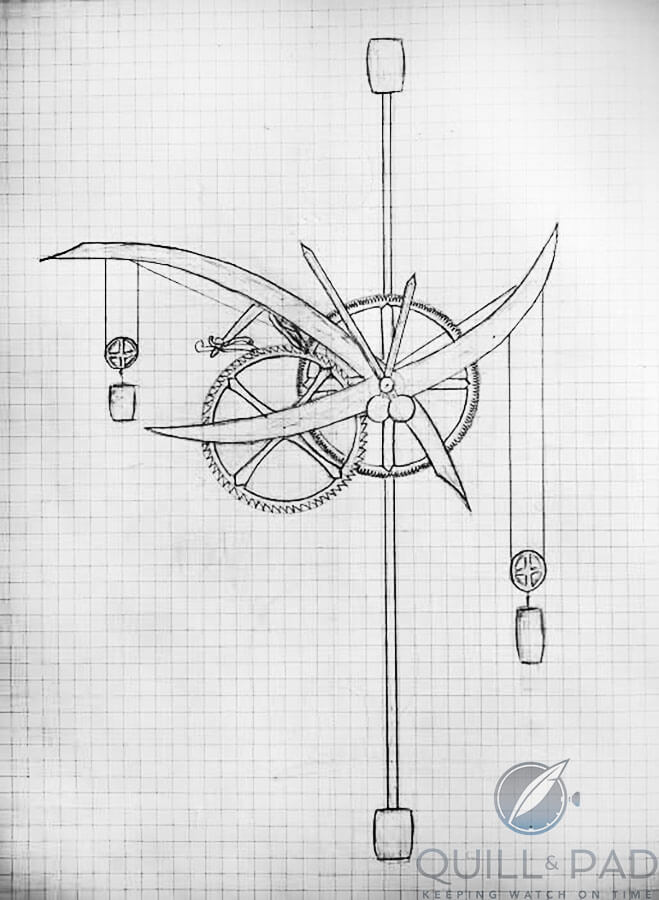

Rick Hale’s first sketch for Wind & Water

Hale has stayed largely true to Harrison’s original design, which he constructed based on a drawing shared with him by Peter Hastings, a noted expert on Harrison and his mechanics and consultant to a team working to recreate two replicas of Harrison’s late regulator. He has been an amazing resource as Hale has worked to utilize Harrison’s designs in his own pieces.

Returning to the grasshopper escapement: its secret is that is doesn’t slide like most escapement mechanisms but instead has pallets that catch and release the escape wheel teeth without much rubbing. Each pallet arm’s distinct shape sees it “fall” onto the escape wheel, hooking the tip of the pallet arm onto a tooth before the pendulum swings the opposite way, allowing the pallet to pop off the tooth as the other pallet arm catches a different tooth.

Wood pallets in the escapement of Rick Hale’s Wind & Water clock

Hale has made a couple adjustments to the mechanism to improve on the original design for his own specific use. The first is to make each pallet arm out of two pieces of wood instead of one solid piece. This allows Hale to take the tip, the area that will actually contact the escape wheel, and rivet on a piece of wood (using tiny brass rivets) with the grain running perpendicular to the length of the arm, which drastically increases its ability to resist breaking since wood is prone to splitting along the grain.

Hale has tested the escapement at full “runaway” speed (where the escapement is driven by the weight without the pendulum controlling the speed) and both the pallet tips and teeth resist the impacts with no issues.

The other modification concerns the composers, which are levers that control the pallet arms’ range of motion when not engaged with an escape tooth. Due to the layout of all the pivots for the pallet arms and composers on this grasshopper escapement, they share a single pivot axis. This simplifies the design of the escapement frame carrying all the components but ends up creating a very wide assembly with all the pieces stacked up next to each other.

To keep the mechanism as thin as possible, Hale made each composer half-lapped at its pivot so they would nest together on the pivot axis, reducing the width by needed by at least a third. This, combined with the entry pallet arm literally pivoting through a gap in the center of the exit pallet arm, makes Hale’s grasshopper escapement very thin yet still robust with the hand-carved cherry and steel shafts.

Ratchets and daisies

The final friction-reduction method Hale uses on Wind & Water is daisy wheel motion works gearing. It sounds delicate but is a very sturdy way to create the proper gear ratios needed to drive the hour hand, eliminating the need for multiple gears. It works by taking the motion of the center wheel, which directly drives the minute hand, and using it to also drive an eccentric wheel that will slowly push the hour hand via a set of pins.

Daisy wheel motion works gearing of Wind & Water by Rick Hale

That eccentric wheel is the daisy and it has round lobes on its exterior and an off-center bushing at its core. Extending off the side of the daisy wheel is a pin that is captured in a slot on the frame of the clock to prevent it from spinning. But as the minute hand rotates the off-center bushing, the daisy wheel slowly oscillates in an eccentric pattern.

The round divots between the lobes then mesh with one of four pins, pushing it a bit before releasing it and pushing the next one along its eccentric path. This continues, creating a 12:1 gear reduction and driving the hour hand to make one rotation for every 12 of the minute hand shaft. It also allows this clock to effectively have one gear, one escape wheel, and one daisy wheel as the entire gear train.

Maintaining power mechanism of Wind & Water by Rick Hale

There are two ratchet wheels as part of the maintaining power mechanism, but they aren’t related to driving the time, so the gear train is effectively those three wheels, which is ultra-efficient. But the maintaining power mechanism is awesome in its own right as it was designed by Hale and allows for the clock to be reset (by pulling on the counterweight to raise the driving weight back up) while continuing to drive the grasshopper escapement (crucial for proper functioning).

Versions of these mechanisms are found on all weight-driven pendulum clocks, but Hale took the time to design one around his style of clockmaking and the result is very clever. Mounted on the pivot axis directly behind the center wheel, the maintaining power mechanism features two ratchet wheels to drive the gear and allow the rope spool to rotate counterclockwise while still providing clockwise force to drive the escapement.

This is fairly standard, however, the connection between the larger ratchet wheel and the center wheel are four long, thin, wooden leaf springs.

These springs are what technically drives the entire gear train by pressing on four steel pins mounted in the rear of the center wheel. They have been carefully hand-shaped to arrive at just the right amount of flex and rigidity to protect the gear train and keep it moving.

There are safety pins near the root of the springs to prevent overextension or breakage, otherwise the wood springs will gently press the center wheel forward during winding of the driving weights.

A few of the wood components of Wind & Water by Rick Hale

Impact and growth

The entire layout of the clock seems to be optimized for minimal friction, minimal part count, and maximum visual effect. With hundreds of individual pieces of wood, Wind & Water is surprisingly clean and minimalist in its execution. The craftsmanship is top notch, and the finishing is straightforward and without pretense. Hale lets the wood and the shapes do the talking.

Wind & Water was under construction around the same time that his earlier KL1 was being constructed, and the functionality is very similar between the two pieces, even if the size and aesthetic is very different. The things Hale learned while constructing the KL1 allowed him to make adjustments to Wind & Water to improve a few aspects.

The pivot and bearing surfaces, for example, have seen adjustments to reduce friction that resulted in a lower driving weight, thinner maintaining power springs, and less strain overall on bearing surfaces. These changes will make their way into KL1 eventually as well as any future pieces.

In the time between debuting the KL1 and Wind & Water, Hale expanded his own skillset and acquired new machinery to produce every component in his own shop, right down to the slotted steel screws fixing wheels to their arbors. This means Hale has complete control over the entire process and has expanded his ability to produce what he envisions. Some commissions have also led to new developments in his wheelmaking techniques as larger wheels have required rethinking how to maintain accuracy and stability over time.

Rick Hale’s specialized machine for cutting grooves in the timer wheel for wooden teeth to be fitted

Acquiring new equipment – sometimes vintage machinery – has really helped with new techniques. Now all of his wheels are bored, turned, slotted, and profiled in a single setup on a Deckel pantograph milling machine sporting a Société Genevoise rotary table. It may be woodworking, but he isn’t messing around: these are serious tools for precision craftsmanship. The results are obvious as Wind & Water is a serious horological creation.

It takes time to create time, and Wind & Water is a great example. Starting as a personal project that was eventually commissioned by a collector, the goal was to shift to an asymmetrical shape from the previous KL1; 2D sketches gave way to a final form that, as Hale puts it, were “Finally worked by my eye.”

From there it took Hale roughly 1,600 man-hours to create the approximately 300 parts, and at three by five feet it isn’t even his largest piece. Hale is currently working on a new commission that is approximately seven by five feet in size and will include an upgraded movement from the one-day (30 hour) power reserve to a more robust eight-day reserve.

Hale continues to develop his ideas while also creating works on commission, often fortunately with the freedom to create what he can imagine, working with clients to produce something with the intended space in mind.

This is a winning strategy. And based on this latest piece, Hale has a bright career ahead of him continuing to create all sorts of stunning objects combining his love for clockmaking and woodworking.

Wind & Water by Rick Hale

I’m glad to be able to share Hale’s latest work with you and at the same time add another incredible clockmaker to my list of favorite American clockmakers to inspire my own creations. Wind & Water is a gorgeous example of hand craftsmanship and a commitment to quality, and with those two things in his pocket (and a firm grasp of the horological concepts in his mind) we are bound to be amazed what Hale creates next!

For more information, please visit www.clockwright.com.

Quick Facts Wind & Water by Rick Hale

Frame: 36” x 60”, hand-shaped figured cherry, quilted maple, lignum vitae, brass, and steel

Movement: 0.5 Hz (one-second) pendulum wall clock with single-pivot Harrison grasshopper escapement, one-day (30-hour) reserve, 11 lb driving weight, 1 lb counterweight

Functions: hours and minutes via daisy wheel motion works

Price: commissioned by client

Note: commissions for pieces similar in size to Wind & Water begin at $35,000; larger eight-day pieces range around $50,000-$150,000 depending on complexity, wood species, and employment of complications.

We can also look forward to a release of a limited run of 15-day remontoir table clocks with moon phase and full moon chime soon.

You may also enjoy:

Eric Freitas: Illustrator Turned Clockmaker Creates Mechanical Fantasies

Miki Eleta Natuhrzeit: Telling The Time Poetically With Nature. And There’s Music Too

Discovering The Secret Of Life With David Walter: Watches, Clocks, And DeeDee’s Tourbillon

The Parmigiani Senfine Concept Features Grasshoppers And Silicon

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!

Hi Rick, I have seen some of your clocks at some of our Nationals and marveled at the beauty of the clocks and the exquisite woods that you use as well as the most interesting designs. I would hope that you would exhibit some of these again.

Dave

FNAWCC, AWCI-CMC

BHI-Assoc. Pritchard

Restoration Award

Freeman WCC